Uncategorized

Toby Fitch: a note on Sydney Spleen

A few years ago, when I was mistranslating Arthur Rimbaud’s prose poems from his Les Illuminations into a variety of inversions (visual poems, formal poems, erasures, anti-lyrics), it occurred to me that I could try a similar project with the prose poems of Charles Baudelaire’s Le Spleen de Paris, another favourite book of mine. However, the same processes – taking the original French and homophonically translating backwards through it to generate weird and wild new poems – didn’t create anything as interesting as that previous project. I began instead to think of Baudelaire’s idea of the splénétique as a mood or mode, and whenever I wrote a poem with a more trenchant, urban realist or political bent, I set it aside in a folder on my computer that I’d named ‘Sydney Spleen’. Over the next few years, some of my more scathing and satirical poems ended up there. Perhaps that folder, and the Baudelairean mood, freed me up to vent my spleen in poetry in ways I hadn’t been doing. The project languished a bit while other quite playful books of mine came to the fore (ILL LIT POP in 2018 and Where Only the Sky had Hung Before in 2019), but 2020 unearthed all kinds of splenetic moods, and so in lockdown, despite four precarious jobs and homeschooling, I found myself writing into the nights to capture the fragmented emotions I was experiencing with my family, and vicariously through the internet, as we watched and re-watched a world seemingly undergoing apocalypse upon apocalypse – megafires, 1 billion animals dying, massive hailstorms and flooding, the ongoing pandemic, the return of fascism ‘like a fossilized piece of moon’ (Ernst Bloch); all symptoms of a broken but still all-consuming capitalist system that allows the ruling classes to exploit the Earth unchecked at the expense of minorities and the working class.

– Toby Fitch

Jenny Grigg wins Australian Book Design Award

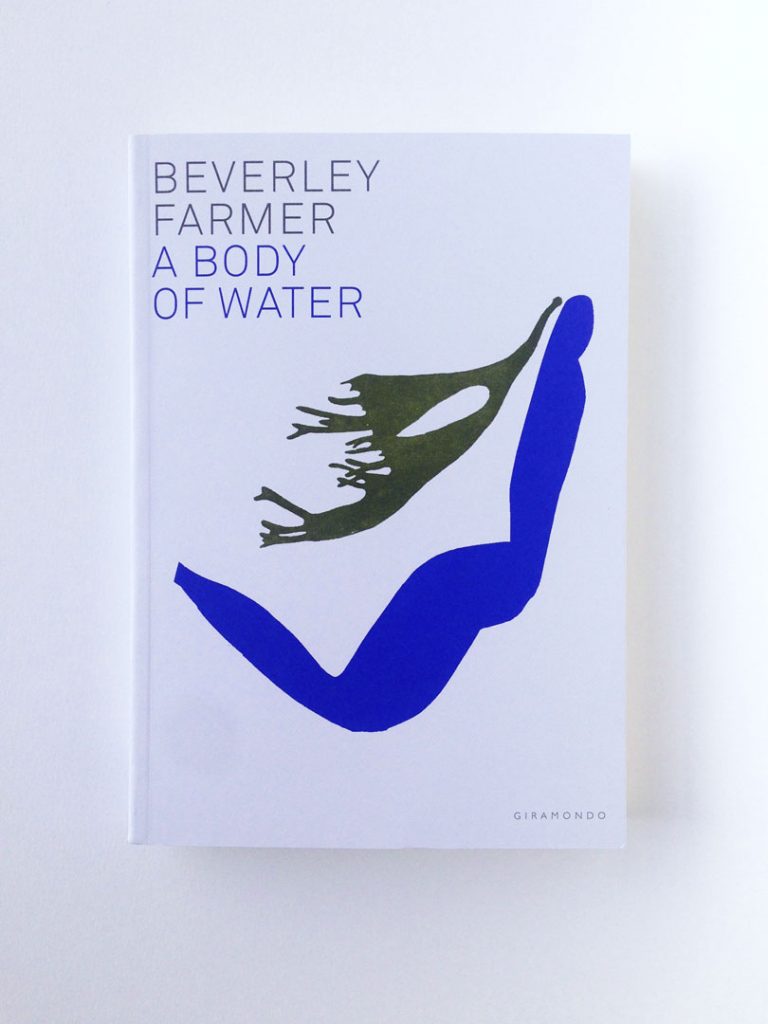

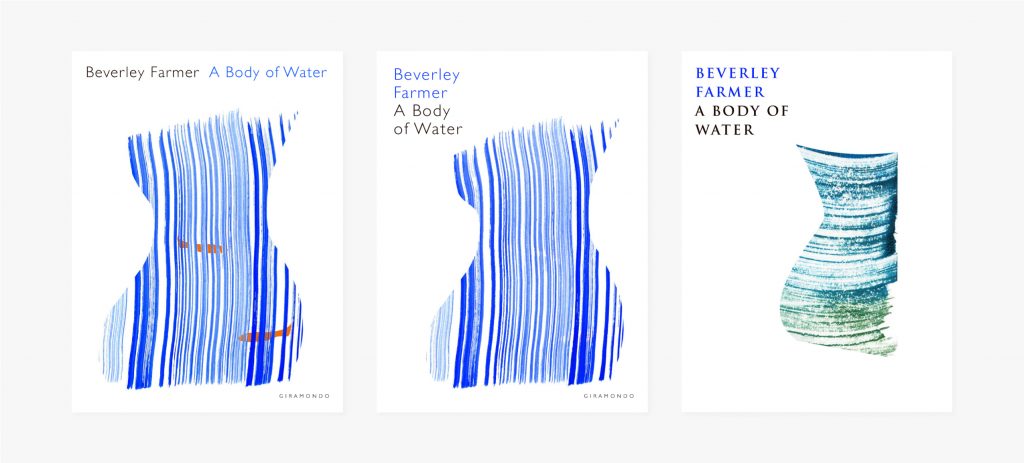

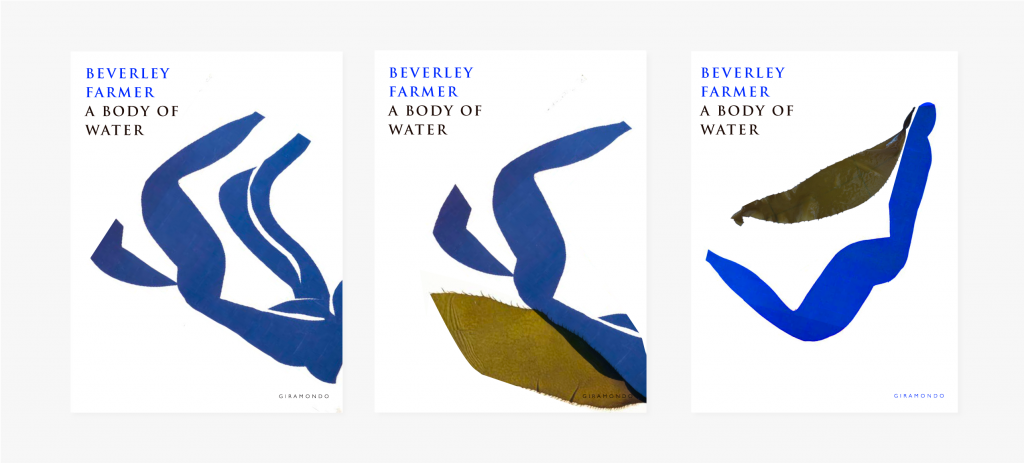

We’re delighted to share the news that Dr Jenny Grigg has won the ABDA award for Best Designed Literary Fiction Cover for her work on A Body of Water by Beverley Farmer. The judges praised ‘the understated simplicity‘ of Grigg’s cover, with its ‘minimal means but maximum effect’.

Grigg designed the cover for this new edition of Beverley Farmer’s out-of-print classic A Body of Water, which in its mixing of genres – essay, memoir, fiction, folk tale – opened up new frontiers for Australian literature.

Early versions of the design responded to a quote from Wittgenstein in A Body of Water:

Human beings are like rivers: the water is one and the same in all of them but every river is narrow in some places, floes swifter in others; here it is broad, there still, or clear, cold, or muddy or warm. It is the same with men. Every man bears within him the germs of every human quality, and now manifests one, now another, and frequently is quite unlike himself, while remaining the same man.

A second point of reference from A Body of Water was Henri Matisse’s 1914 painting Intérieur, bocal de poissons rouges (Interior with a Goldfish Bowl). The shape suggests Farmer herself, in its female form, and also a vase, and contains textures to reflect Farmer’s affinity with the sea. The fish were eventually removed to reference Farmer’s ‘body of water’ more directly than the Matisse painting.

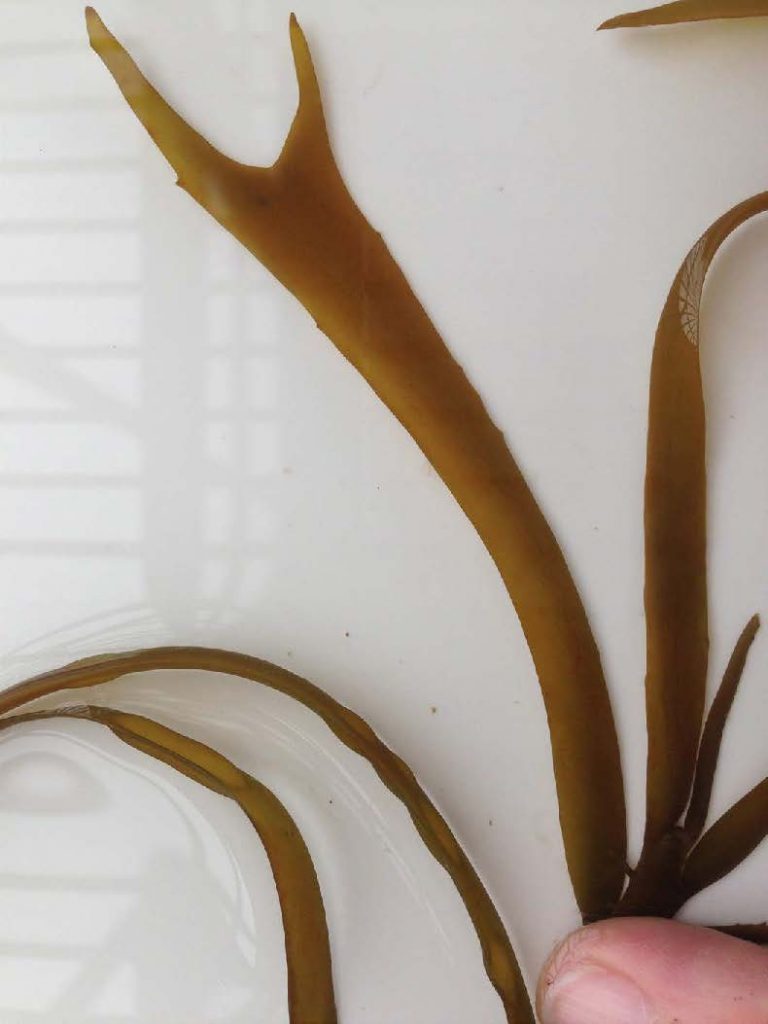

Responding to a photograph of Farmer sitting on a rock by the sea, an alternate reference to a mermaid was conceived, collaging a fragment of seaweed and a rotated section of Matisse’s cutout Blue Nude with Hair in the Wind. Whether diving out of frame, or weightless and floating seahorse-like – the final design was chosen from these and other possibilities for its clarity and vigour. The collaging of shape and colour are relatively inexpensive, expressive tools in the context of book cover design.

In her ABDA entry, Grigg describes the rationale for her final design:

The cover design is a visual metaphor for the title and the fugitive spirit of the author as she reflects about her life in her 46th year, living alone by the sea after the failure of her marriage. The juxtaposition of a section of a Matisse cut-out, and a piece of seaweed portray her as a mermaid. Matisse is a theme within the book, and seaweed signifies her life lived by the sea. Throughout, one is aware of the writer’s own body, as an entity which shifts its identity like water, with its changes of mood, relationships and reflections.

Grigg is Giramondo’s publication designer and a lecturer in the School of Design at RMIT University. She has won multiple design awards, a 2011 State Library Victoria Creative Fellowship and induction into the Design Institute of Australia’s Hall of Fame in 2020. Her design for A Body of Water was also a finalist in the 2020 Australian Graphic Design Association Awards.

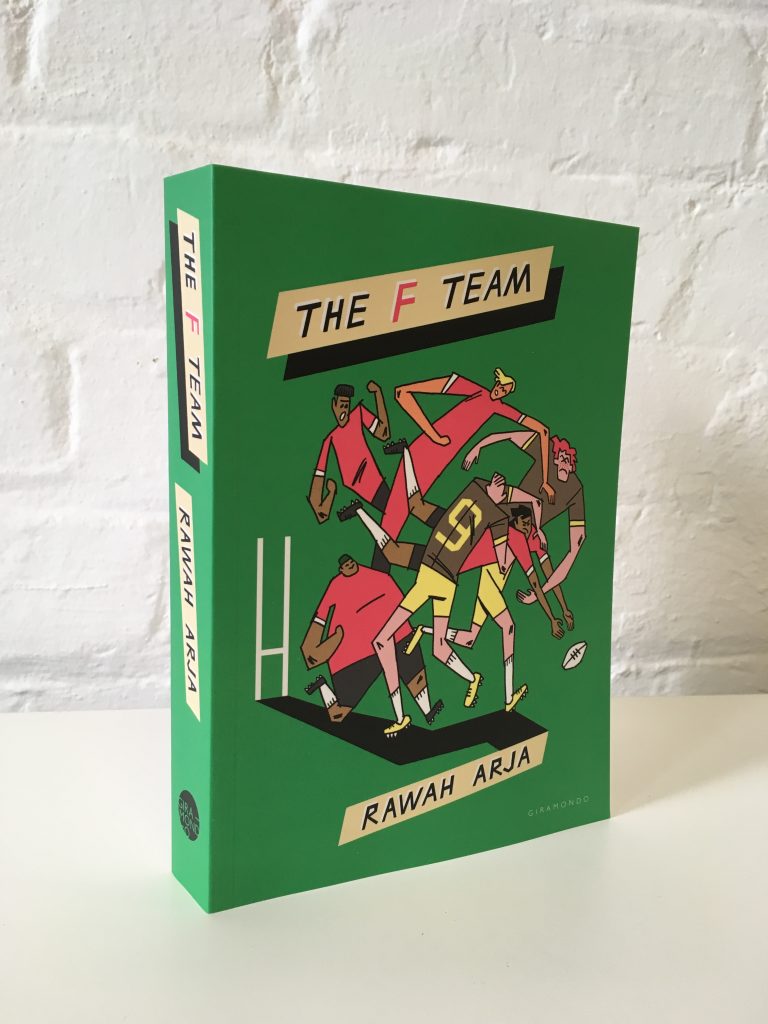

Ben Juers highly commended in the ABDAs for Best Designed Young Adult Cover

We’re pleased with the news that Ben Juers was highly commended in the Best Designed Young Adult Cover award for his illustrated design for Rawah Arja’s The F Team at last week’s Australian Book Design Awards, with the judges commenting:

Innovation is always bound to impress, with The F Team featuring a bold illustration that evokes drama and interesting typographic treatment [which] combine to create an eye-catching cover which breaks the mould of young adult covers.

Describing the rationale for the cover, Juers said:

In designing the cover for Rawah Arja’s The F Team, I aimed to reflect the story’s anarchic energy, and make it stand out from other Young Adult novels. I wanted to strike a balance between precision and chaos, in keeping with the nature of rugby (around which the story revolves) and the dynamics underlying it, which are constantly in flux: friendship, animosity, cultural difference, masculinity. To this end, I looked to the expressionist, off-kilter charm of Lyonel Feininger and the efficiency of European ligne claire cartooning as models.

Ben Juers is a cartoonist, book cover designer and teacher. He is a co-ordinator at Glom Press and a member of Workers Art Collective, Trades Hall Artists Studio, Workers Solidarity and Other Worlds Zine Fair. Follow him on instagram @benjuers.

The F Team shortlisted for two awards

We are delighted to share the news that Rawah Arja’s The F Team has been shortlisted for two new awards. Her debut novel is nominated for the Russell Prize for Humour Writing and the 2021 Readings Young Adult Book Prize.

The Russell Prize is Australia’s only prize for humour writing and is awarded biennially, with this year’s winner to be announced at an event at the State Library of NSW on 17 June. Tickets are available on Eventbrite.

The Readings Young Adult Book Prize is awarded annually to the best new contribution to Australian young adult literature. This year Arja is nominated alongside five other authors, with the winner to be announced on 15 July.

The F Team has been recognised with nominations for several major literary awards including the New South Wales and Victorian Premiers’ Literary Awards, the Australian Book Industry Awards, the Children’s Book Council of Australia Book of the Year Award and the Australian Book Design Awards.

Book launch: Unanimal, Counterfeit, Scurrilous by Mark Anthony Cayanan

To celebrate Mark Anthony Cayanan’s new poetry collection Unanimal, Counterfeit, Scurrilous, the author will be joined in a free online conversation about their book with poet Eunice Andrada. The event will include readings from the book.

Wednesday 9 June, 7 p.m. (AEST)

Online | Free, RSVP essential | Register on Crowdcast

About the book

Unanimal, Counterfeit, Scurrilous is a work of wild erudition and rococo elaboration, a collection of poems that loosely channels the dynamic of desire and inhibition in Thomas Mann’s novella Death in Venice. The poems follow the trajectory of the ageing Aschenbach’s pursuit of youth and beauty, transmuting his yearning and resistance into jittery flirtations with longing, decay and abandonment against a backdrop of political violence. The poems have an exuberant candour, formed by polyphonic allusions which enact the intersectionality of the speaker, by turns melodramatic and satirical. Like the tragic protagonist of Death in Venice, Cayanan’s collection manifests a longing for extroversion sabotaged by its own will. It is a queer performance of anxiety and abeyance, in which the poems’ speakers obsessively rehearse who they are, and what they may be if finally spoken to.

About Mark Anthony Cayanan

Mark Anthony Cayanan is a poet from Angeles City, Philippines. They obtained an MFA from the University of Wisconsin in Madison and are a PhD candidate at the University of Adelaide. Among their previous publications are the poetry books Narcissus and Except you enthrall me. They teach literature and creative writing at the Ateneo de Manila University.

About Eunice Andrada

Eunice Andrada is a Filipina poet and educator. She is the author of Flood Damages (Giramondo Publishing 2018), which won the Anne Elder Award and was shortlisted for the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award for Poetry. Born and raised in the Philippines, she now lives and writes on unceded Gadigal Land. TAKE CARE, her second collection of poetry, will be published by Giramondo in September.

Dong Li: a note on The Gleaner Song

I got to know Song Lin well while at Ledig House for a Translation Lab residency. On a long walk in the countryside of Upstate New York, I saw his eyes light up as a deer leapt from the wild into a wide-open field. As the evening hues shifted farther into the forest, his line of sight followed the deer until it vanished into the night. We talked about the deer, and later he asked me to translate a poem that he had written to record the occasion. This is a curious poet who opens himself to the world around him. His songs migrate from one word to another, from one language to another. The landscape of his travels becomes a map of his poetry, which, in turn, amounts to a sensitive anthropology of our migratory world.

Not unlike his predecessor Bei Dao, whose candid declarations of resistance marked the tenor of the time, themes of politics and exile permeate Song’s poetic output. When the Tiananmen event exploded in Beijing, Song led student demonstrations in Shanghai and was imprisoned for almost a year. But unlike many self-claimed ‘exiled poets’, Song has never used imprisonment to his advantage. Instead, what has interested Song is the joy of making art out of words and how poetry can group words and form company. His joy in poetic expression led to his lengthy wanderings through France, Singapore, and Argentina. These heightened his sense of language and its central role in his poetry.

Song has been somewhat neglected in his native language. Political pressure was the unspoken background. During those wandering years, his two formidable titles Fragments et chants d’adieu (Fragments and Farewell Songs) and Murailles et couchants (City Walls and Sunset) appeared in French bilingual editions. He was unable to publish in China then, so he used his editorship with the eminent journal Jintian to scout out and publish poets living under difficult circumstances. Since his return to China, he continues to support young poets and champions translation. Unlike many poets who are eager to please Western ears, Song advocates for the classics and for a thorough study of the Chinese language. When dividing lines between different camps of poetry and poets widen, Song is the one, not to force cohesion, but to promote tolerance and understanding.

Song’s faith in poetry and his generosity towards poets across aesthetic, generational, and national boundaries make him one of the most unusual poets to have emerged in recent Chinese history. His poetry weaves through American, classical Chinese, French, and Latin American traditions. His influences are the modernists, the surrealists, the romantics, the deep imagists and the objectivists – but what distinguishes Song is his ability to take them all, and make them his own, and make them new. His is a lyric that continues to open up horizons.

– Dong Li

Giramondo seeks editor for new HEAT magazine

With the support of the Australia Council and Western Sydney University, Giramondo Publishing will recommence the publication of its renowned literary magazine HEAT in 2022, in a new series, and a new format.

To this end, we are looking to appoint a skilled and innovative editor to oversee the planning, commissioning and publishing processes of the new HEAT. Applicants should have university qualifications in literature or a related field, an advanced understanding of the contemporary literary scene, and experience in editing and publishing. They should be skilled in the relevant software, and have the ability to seek out and interact with contributors to and readers of the magazine. A sensitivity to the diverse styles and voices that constitute contemporary Australian and international writing, and to the strengths of emerging and established writers alike, are also essential characteristics. Intending applicants should be acquainted with the range of Giramondo’s publications, and with the two previous series of HEAT.

The HEAT editor will work alongside the Giramondo team at our Redfern office, and will be involved in our discussions about publishing schedules, design, printing, promotion and publicity, and funding. Working remotely is also an option. The position is a part time 0.6 appointment, from July 2021, and includes superannuation and annual leave. The salary is to be negotiated, in line with book industry standards.

Expressions of interest for the position of HEAT editor are to be submitted to applications@giramondopublishing.com by 5pm Monday 31 May. A one-page letter outlining your qualifications for the position should be accompanied by a CV which lists two referees. Please include these in a single file, with your name as the file name.

No Document launch events in Sydney and Melbourne

Please join us to launch Anwen Crawford’s book-length essay No Document at events in Sydney and Melbourne.

Melbourne

We’ll be celebrating the publication of No Document in Melbourne with an event at Dancehouse, co-hosted with Paperback Bookshop.

The book will be launched by writer and editor Elena Gomez, and Anwen will be in conversation with Dion Kagan.

Friday 14 May 2021, 6pm

Dancehouse, 150 Princes St, North Carlton

Free, RSVP essential

Sydney

Join us in launching No Document at Gleebooks, with readings by Emma Davidson, Vanessa Berry, Tim Roxburgh and Anwen Crawford.

Sunday 23 May 2021, 2:30 for 3:00 pm

Gleebooks, 49 Glebe Point Road, Glebe

Free, RSVP essential

Alice Whitmore wins the NSW Premier’s Prize for her translation of Imminence

Congratulations to Alice Whitmore, whose translation from Spanish of Imminence by Mariana Dimópulos is the joint winner of the 2021 NSW Premier’s Translation Prize. Imminence is the second novel by Dimópulos that Alice Whitmore has translated, following Giramondo’s 2017 publication of All My Goodbyes.

Watch Alice’s acceptance speech and read the judges comments below:

This beautifully conceived and crafted novel makes time stand still, as a new mother is filled with an absence of feeling for her baby. Taking place over an evening and a lifetime, the narrative unfolds in circular, spiralling scenes and meditations without ever losing its focus. The fragmentation of singular moments builds to a strangely satisfying ending. This work pulls readers into a slow burn treatment of trauma that is entirely present but also part of a complex psychology inflected by all that has come before.

Elegant and precise, this work is subtle in its intrigue, offering readers the freedom to weave their own conclusions as they retrace the woman’s life over 20 years: her lovers and friendships, a country cousin, mathematical formulae, deserts. Through a dexterous mix of dreamlike, real and delusional emotions and atmospheres, this fluent translation superbly conveys the peculiar and economic use of the writer’s language and style.

Imminence opens up its characters’ lives like complex clockwork, taking us into parts usually concealed to wonder at the deeper philosophical mysteries of time, truth, perception and one’s struggle to know others. The translation reads flawlessly in its rendition of the lyrical strangeness, detachment and beauty of the author’s compelling voice and vision.

Judges’s report

Alice Whitmore is a writer and literary translator living on Gunditjmara country. Her translations from Spanish to English include Mariana Dimópulos’s All My Goodbyes and Imminence, Guillermo Fadanelli’s See You at Breakfast?, and Xhevdet Bajraj’s Collected Poems. She is the translations editor at Cordite Poetry Review and an associate editor at Giramondo.

View the full list of winners at the State Library of NSW website and watch the full announcement on the SLNSW Youtube channel.

Giramondo designers shortlisted for Australian Book Design Awards

The shortlisting of our designer Jenny Grigg, for Beverley Farmer’s A Body of Water, and illustrator Ben Juers for Rawah Arja’s The F Team I take as recognition of the important role design plays in the production of Giramondo’s books. Both Jenny and her predecessor Harry Williamson, who did much to establish Giramondo’s reputation as a literary publisher, have been honoured as members of the Design Institute of Australia Hall of Fame. I have always felt that literary quality demands quality in design as its partner.

Jenny’s design for A Body of Water is a distinctively contemporary homage to Henri Matisse, whose painting Vase with red fish plays an important role in a short story embedded in the mosaic which has made Farmer’s work a classic of Australian literature. At the same time, it expands the resonances of Farmer’s title, A Body of Water.

Ben’s cartoon-like representation of the clash of young football titans on the cover of The F Team captures the combination of energy, social tension and comedy though which Rawah’s novel has expanded the range of Young Adult fiction, just as it makes its own dynamic contribution to the cover-design possibilities for this popular genre.

— Ivor Indyk

See more of Jenny’s work at jennygrigg.com.

Ben is on instagram @benjuers.

No Document – a playlist and liner notes

Anwen Crawford presents an essay in the form of liner notes about the making of No Document.

SIDE A

Mission of Burma – Mica, from Vs., 1982

Well y’know I nearly called the book Mica, because of my long preoccupation with this song’s ability to disassemble itself from the inside, as if the thing were always in the midst of becoming something else. Starting again. One of the best gigs I’ve ever seen in my life was about twenty years ago, this short-lived band called The Unicorns (right?), and at the end they started taking apart their equipment as they were playing, passing bits of the drum kit and the mic stands out into the audience. That’s how all gigs should end (or begin). Let’s democratise the means of production. Starting again.

Tropical Fuck Storm – Rubber Bullies, from A Laughing Death in Meatspace, 2018

The course of history is never pre-determined, but if I am testing a thesis in No Document then it’s the one voiced here: Certain pasts want certain futures / Certain futures, certain pasts. The arrangement of this song is repetitious, unremitting; it’s about causality – what it takes away – where Mica is about improvising new realities (I think). Is anything still possible?

Nina Simone – Pirate Jenny (live), from Nina Simone in Concert, 1964

As exacting and as merciless an act of class vengeance as has ever been delivered onstage. The show is over. The audience get up to leave their seats: time to collect their coats and go home. They turn around. No more coats and no more home.

Silver Mt. Zion – Mountains Made of Steam, from Horses in the Sky, 2005

This kind of folk-punk, post-rock thing that was floating around in the early 2000s got on some people’s nerves for the same reasons I love(d) it: a stubborn naivety of spirit and tone, the refusal to stop asking the question of why the world is as it is, and asking it with the resources to hand, i.e. your battered guitar amp and a ragged group of voices. This is their busted future / And this is our dream / Which one do you believe in?

Broadcast – You and Me In Time, from Tender Buttons, 2005

Broadcast’s vocalist, Trish Keenan, died suddenly in early 2011, only a few weeks after the death of my friend for whom No Document is written. I’d seen them play live just before he died; they too were a duo.

The Ink Spots – I Can’t Stand Losing You, 1943

For years now I’ve played a game in my head: is this a break-up song or an elegy?

Suede – The Wild Ones, from Dog Man Star, 1994

All great Suede songs – and this is probably the greatest – are about the drama of being young. And though The Wild Ones is probably addressed to a lover, I think its majesty encompasses the love we have for our friends when we’re young enough to rescue each other, wreck each other. And oh, if you stay / We’ll fly from disguised suburban graves. Well, amen.

Dinah Washington – This Bitter Earth, 1960

This song, on the other hand, is about no longer being young. Among other things.

Diamanda Galás – Let My People Go (live), from Plague Mass, 1991

Performed in the Cathedral of St John the Divine, New York, at the height of the AIDS epidemic in that city, Plague Mass by Diamanda Galás was (and is) an act of radical mourning. Her work as a singer and musician has been dedicated to the politics and rituals of grief: who grieves, who is grieved, how we might grieve together. Galás warns – this is news from below – that those whose grief has been occasioned by the state have no obligation to forgive.

SIDE B

Pet Shop Boys – Being Boring, from Behaviour, 1990

From one elegy to another, very different in tone but no less moving to me. This song wears its grief lightly. My friend V once described Neil Tennant as possessing ‘a teardrop voice’, which is exactly right: even when he’s arch (which is most of the time) he’s also sad. Being Boring can make me cry and there are few songs of which that’s true. Also – and I’m gonna let you in on a secret here – part of the reason I was determined to get Pet Shop Boys into my book was in order to impress my friend Shaun Prescott, who once wrote a great zine about them. I hope you’re duly impressed, Shaun.

Life Without Buildings – The Leanover, from Any Other City, 2001

It remains one of my minor but lasting regrets that I passed up the chance of seeing Life Without Buildings, a band of former art school students, at the Annandale Hotel, when I was an art school student. ‘They’ll be back’, I thought. Reader: they never came back. There was a season around this time, this year, when I had bronchitis – contracted, I believe, during too many winter nights spent outside spray-painting – and I lay in bed for what felt like months, but was probably only weeks, listening to this record and contemplating the floorboards.

The Clientele – Losing Haringey, from Strange Geometry, 2005

When I look back at this there’s nothing to grasp, no starting point. I was inside an underexposed photo from 1982 but I was also sitting on a bench in Haringey.

Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell – Ain’t No Mountain High Enough, 1967

There’s a specific kind of intimacy generated by collaboration. Were they partners? No. Were they partners? Yes. I tend to assume from this recording that, among other things, Tammi Terrell and Marvin Gaye shared a similar sense of humour: it’s their timing, their exuberance, the bounce of this song, though their parts – this was their first duet – were recorded in separate sessions. Tammi Terrell died at age 24, of brain cancer.

Stay – Rihanna feat. Mikky Ekko, from Unapologetic, 2012

My friend for whom No Document is written was, at heart, a not-so-secret sentimentalist (as I am), and had he been alive when this song was released, I like to imagine that we would have spent many happy hours singing along with it, badly, in his car.

I Found a Reason – Cat Power, from The Covers Record, 2000

This one I don’t have to imagine: we used to sing along to Cat Power all the time.

Limerence – Yves Tumour, from the compilation Mono Non Aware, 2017

VHS / mixtapes / colour snapshots /

Your voicemail greeting outlasted you

New Grass – Talk Talk, from Laughing Stock, 1991

A long time ago I learnt that the secondary and largely forgotten meaning of the word aftermath is ‘new grass’: that which grows after the harvest. The singer of this song has passed through to the other side of an event, but I don’t know what that event is; none of the words are discernible to me, and I’m glad of that. The song is a silhouette, not a testimony.

Who Knows Where the Time Goes – Nina Simone (live), from Black Gold, 1970

And above our heads pass birds, casting their shadows.

Giramondo authors at the Sydney Writers’ Festival

Several Giramondo authors will feature in the 2021 Sydney Writers’ Festival, which runs from 26 April to 2 May.

Anwen Crawford will be in conversation with Alison Croggon on 29 April and join a panel on criticism and creative practice on 1 May.

Fiona Kelly McGregor will appear at the festival gala event, Within Reach, on 30 April, while Rawah Arja joins YA authors for Disaster Kids in Love on 1 May.

Yumna Kassab and Felicity Castagna are both participating in Words/Sounds, a performance featuring five writers and five electronica artists in Parramatta on 29 April.

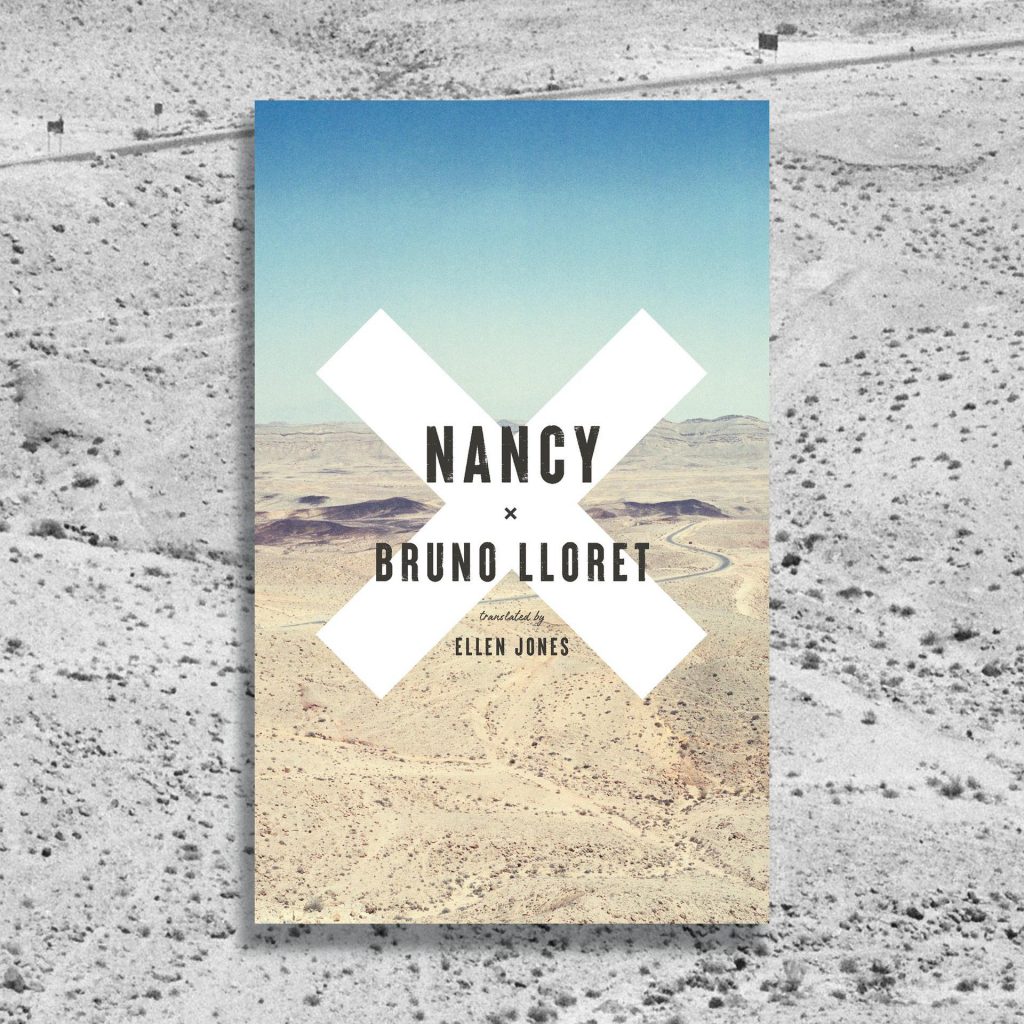

US edition of Bruno Lloret’s Nancy published by Two Lines Press

Chilean author Bruno Lloret’s novel Nancy, translated from Spanish by Ellen Jones, is reaching new audiences with a US edition published this month by Two Lines Press.

Lloret’s book is distinguished by its remarkable visual qualities, most evident in the free-flowing use of X characters throughout the text – characters which might also suggest religion, erasure, death, disappearance – and in the use of photos, x-rays and other graphic material.

The X started, almost on its own, to gather other functions than rhythm – silences, white noise, gaps, breathing,‘as if the world depicted in the novel emerged from the many meanings of this ubiquitous sign.

Bruno Lloret on Nancy

Most of all, Nancy is propelled by the strength of its narrator’s voice – spare, tender, ironic, and marked by an incorrigible optimism against the tragic precariousness of her life. Crippled by cancer and abandoned by her family, she tells her story from childhood through to its final moments, amid the ecological and cultural devastation of the northern Chilean hinterland.

The new edition has been greeted with strong praise:

this extraordinary novel far transcends denunciation and the exercise in style, reaching a new, unexpected, dissident realism.

Alejandro Zambra

The novel heralds a vanguard in Chilean letters and, despite its local roots, belongs to a burgeoning international literature of shared crises.

Asymptote

Bleak, beautiful and incredibly powerful.

Kirkus

This visually striking fever dream is one worth braving.

Publishers Weekly

In celebration of the new edition the Center for the Art of Translation a hosting a virtual event with Bruno Lloret, translator Ellen Jones, and moderator Kathryn Scanlan in conversation on Friday 23 April at 10:30am Australian Eastern Time (22 April, 5:30pm Pacific Time). Register for free here.

And Ellen Jones interviewed Bruno Lloret for the Southwest Review:

Nancy places a lot of emphasis on adobe, as well as on other desert materials, mountains, walls, abandoned iron constructions, even sand. Those materials are repositories for voices, and so is Nancy’s body—it’s a kind of resonance box, like in a guitar. Her body is a record of the scenes she has lived and the words she has spoken, and in turn the book itself is a record of those words, contaminated with Xs like her body is contaminated with cancerous cells. And so the book explores the parallels between landscapes, bodies, and texts.

Nancy was published in Australia by Giramondo in March 2020 and is the sixth title in Giramondo’s Southern Latitudes series, focused on writers from the Southern Hemisphere. It is the first of Lloret’s works to be published in English.

Anwen Crawford: a note on No Document

At the dead-end of Jones Street, which runs behind the distinctive tower building of the University of Technology, there once stood the shell of a former flour mill, hard up against the Western Distributor. I used to wander it. We used to. Rode out there with my friend, dragging Dulux tins and rollers on a jerry-rigged trailer behind our bicycles, through Sydney’s streets, to paint BIT BY BIT THE CITY BEWILDERS US onto one of the mill walls. Our message faced the road, so that passing drivers could read it. It lasted a few days.

The site of the mill is a luxury apartment block now, and my friend is dead. In the decade since his death I’ve often wondered how our we was brought into being. The friendship elegised in No Document is a we that existed at a time in Australia when the issue of who we were or are as Australians was heavily contested – when isn’t it? – by Tampa, by the offshore mandatory detention of asylum seekers, by the protests and resistance of those inside and outside detention centres, by Australia’s involvement in the War on Terror and the 2003 invasion of Iraq. I was heavily involved in student activism at this time, and attended many protests, some of which still haunt my dreams. So did my friends. We were young then and we are not now, those of us who live.

My hope is that this book serves as an elegy not only for one specific person but for those, including animals, who have been excluded from the social contract, from the we of belonging. Mourning is always political: the question of who can be grieved, who counts as having lived, is a contested one. I also think that the defining characteristic of an elegy is the labour it takes to make it. One attempts to honour the dead with one’s effort, attention and love.

In this sense, No Document is an incomplete record of its own becoming: incomplete because what’s left on the printed page are only the thoughts that I was equal to expressing, bit by bit. But the future – and the past – still contain possibilities that will exceed what I can say.

Mark Anthony Cayanan: a note on Unanimal, Counterfeit, Scurrilous

I was mainly preoccupied with two things when I was working on Unanimal, Counterfeit, Scurrilous. The first is more obvious: the collection plays out my obsession with Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, which I was initially drawn to as an undergraduate because of how opaque its object of desire was (I didn’t fully realise back then that objects of desire in literature were almost invariably rendered as opaque entities) and how a plot marked by stasis – the entire novella is pretty much just a disastrous vacation – serves as a front for the implosive trajectory of the protagonist’s inner life. Throughout the process of engaging Mann’s narrative in a conversation, I was mindful that I was coming from a position that isn’t entirely compatible with the rarefied conditions of his queer tragedy.

The second is just as important: in the pre-pandemic era when I was working on the poems, the Philippines was, and continues to be, in the midst of a protracted campaign against illegal drugs. Initiated by a populist president, the campaign has been used to justify the flagrant violations of human rights committed with impunity by agents of the state, including extrajudicial killings of suspected drug users, peddlers, journalists, and political opponents of the government; the curtailment of press freedom; and the red-tagging of activists and representatives of Indigenous groups. Like many other artistic producers, I felt the compulsion to channel through my work the rage and despair I kept feeling in the face of such undeniable state-sponsored violence – but I honestly didn’t know how to participate in a socially necessary public discourse, when doing so also felt like being conscripted into a literary economy in which activism is transmuted into cultural capital. Moreover, I was an international student at the University of Adelaide; and I couldn’t quite shake off the suspicion that there was something mercenary about obtaining a PhD out of making the atrocities in my country legible to what was immediately a foreign audience (they were barely legible to me).

I dealt with this paralysis through subterfuge: one of my fundamental acts of creation was appropriative. Like a modernist or magpie, I stole conflicts and words, embedding passages into poems or actually creating drafts out of swathes I cobbled together from various sources. I imbricated texts detailing the political situation in the Philippines with Death in Venice, of course, as well as other materials whose presence enacted, albeit spectrally, the intersectionality of the subject-position from which the poems emerged. Instead of unambiguously deploying my work as political content, I attempted, through the plagiarism-adjacent methodology, to privilege the potentialities of the poem as a site of struggle while also demurring on it being a purveyor of radicalising motion. By nestling the social relationalities informing the collection within its climate of interiority, it is an anxious and queer performance of abeyance.

Nothing to See: Pip Adam in conversation with Laura Jean McKay

We’re glad to share the video of Pip Adam and Laura Jean McKay, author of the award-winning novel The Animals in That Country, in conversation about Nothing to See. Framing the novel as a meditation on care, they speak to themes of dividing and reforming, loss and loneliness, and embodied experiences of writing and reading.

I was thinking about the loneliness of not being seen…I really want to tell stories that I think have been silenced and I’m trying to find ways of telling these stories that somehow can be consensual with the reader

Pip Adam on Nothing to See

We’re grateful to Readings for hosting this online event, and for allowing us to share the recording.