Claiming the Colossus

In 1958 when I was eight years old my parents took me to New York. I fell in love with its powers of abstraction. It became the city of my mind. In 1988 we took our son to New York. He was eight, and the same thing happened. Now, the door to his room is covered with a large map of midtown Manhattan in detailed axonometric projection. He reads books about places and technologies and is thinking of becoming an architect.

One book he may find on the shelves is the 1978 publication Delirious New York by Rem Koolhaas. It is now a classic, with a wealth of history, analysis and anecdotes, a pleasure to read, until you come across a short sub-section titled ‘Woman’. This expresses the notion that ‘Architecture, especially its Manhattan mutation, has been a pursuit strictly for men. For those aiming at the sky, away from the earth’s surface and the natural, there has been no female company.’ Woman, it appears, ‘stands for the continuing embarrassment caused by the biological functions of the human body that have proved resistant to lofty aspirations and technological sublimation.’

No lofty aspirations? How can that be?

But I remember that Alice in Wonderland, who had certainly had several away-from-the-earth’s-surface experiences, came across a similar problem with the Mad Hatter. ‘Alice felt dreadfully puzzled. The Hatter’s remark seemed to her to have no sort of meaning in it, and yet it was certainly English.’

My Lips My Tale My Tongue

Charlotte Brontë’s Villette was published in 1853. Loosely autobiographical, it is the story of a poor and timid Englishwoman, Lucy Snowe. She is obliged to go and teach at a school in Belgium and there falls in love. The whole long novel involves us in her divergent and arduous ascent towards that great nineteenth-century peak: self-expression.

The story reaches for its magnificent climax, with the once socially isolated and somewhat repressed heroine drifting sensuously through the carnivalesque buzz of the crowds, the music, and the spectacle of a midsummer night’s fête. As Alice nibbled mushrooms and drank potions, Lucy is also under the effect of a catalyst, a ‘medicated draught’. With ‘imagination roused from her rest’ – indeed, threatening to ‘run riot’ – Lucy realigns herself with a set of ‘companions’, Renovation, Freedom and the man she loves. He encourages her to tell him her story of ghosts in garrets and melancholy walks in secret gardens. ‘I spoke. All leaped from my lips. I lacked not words now; fast I narrated; fluent I told my tale; it streamed on my tongue.’

The sexuality of articulation – not to be confused with the articulation of sexuality – represents the most significant series of landmarks in the history of women’s writing. At the very end of Villette, as Charlotte Brontë stands behind Lucy Snowe to survey the narrative scene from the summit, it becomes clear to both heroine and author (and to us) that it is in desire that this novel has been conceived and spun out. And so to make the point – that aspiration and attenuation are essential players in the sexuality of articulation – the object of desire, the lover, is once more removed. Villette does not end in fulfilment after all. Cleverly, to leave hope to those with ‘sunny imaginations’, the author contrives not to have the novel end at all.

Before the couple’s life together can begin, the hero goes on a long journey. We are told about a terrible storm. Then we are left to guess whether he ever returns. But during his absence and in anticipation of their reunion, Lucy thrives emotionally and financially. ‘The spring which moved my energies,’ she notes, ‘lay far away beyond seas, in an Indian isle.’ The hero is gone for three years. ‘Reader, they were the three happiest years of my life. Do you scout the paradox?’

Well? Do you?

Cleopatra’s Needle

In 1854 Anna Elizabeth Blunden painted The Seamstress. This painting has become an icon of the fight against the exploitation and isolation of women’s labour. The focus is on a woman pausing from her work. A wealthy person’s shirt awaits her attention, one sleeve hanging down as if imperiously insisting on her stooping again over the task at hand. But instead she clasps her own hands in prayer. Her face is turned up at the patch of sky visible through the window. The lines of window frames, of nearby roofs and chimney stacks accentuate that upward thrust of her eyes, the straining whiteness of which is central to the painting’s theme of elevation. By leaning out of the window and looking up, heavenward, the seamstress takes us physically between the horizontal and vertical seams and stresses, the socio-symbolic planes of her – and the artist’s – work. In the distance there is a townscape of needlesharp spires. In the foreground, the woman aspires beyond her given condition.

Her body in prayer is the closest an essentially silent painting may get to the novelist’s kind of articulation, of internal monologue externalised. Blunden’s melodramatic trick, the simultaneous inversion/extroversion of the woman’s eyes signifies also a subtly paradoxical treatment of scale. On the visual conveyor between nearness and distance, the laws of perspective have been enlisted to render the churchtowers small and faint, while the poor seamstress, like Charlotte Brontë’s Lucy Snowe, looms large in our imagination: giants in woman-land.

Brontë’s heroine, cut off from all protection – her family, country, language – loves a ‘despotic’ little man, an archetypal father-figure. When she finally exhausts her speech, ‘he gently raised his hand to stroke my hair; it touched my lips in passing; I pressed it close, I paid it tribute. He was my king; royal for me had been that hand’s bounty; to offer homage was both a joy and a duty.’ Villette concentrates on the fulfilment not so much of Lucy’s sexual desire as of a larger sense of ‘bounty’, of good(s) received.

In Blunden’s work, the seamstress scans the sky for an inherent power, for an inheritance. God is not in evidence, except by implication on the one hand in the watery calligraphy of church buildings on the horizon, and on the other hand, in the woman’s pose. Which of the two, the institution of the church or the solitary woman (the painting’s rhetoric seems to demand), is the more deserving heir?

Mouse and Mastodon

Heaven and earth, as Koolhaas knows, are not easy fabrics to match. But through the depiction of what one might otherwise assume to be a hunched and squinting seamstress as a far-seer, Blunden has also painted a type of heiress. While not denying their femininity, nor distancing themselves from their mothers, nineteenth-century literary heroines are insistent on their masculine lines of inheritance.

Like Lucy Snowe, the heroine of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh is also orphaned. This orphan status allows the heroines to reassess themselves, to make their lineage, their resemblances less predictable. In Browning’s epic poem, as in Villette, the gesture of placing a hand on another’s head appears as a particularly enriching moment. At the very beginning of the work, the narrator recalls how as a child ‘Still I sit and feel/ My father’s slow hand…/ Stroke out my childish curls…’ And when her cousin (whom she will later marry) assumes a similar intimacy, there’s a shocked reaction. ‘I rose and shook it off as fire,/ The stranger’s touch that took my father’s place…’ Thus the child Aurora situates herself. ‘I am like,/ They tell me, my dear father…’

This father had once taken her education upon himself, and generously sharing all his knowledge ‘wrapt his little daughter in his large/ Man’s doublet, careless did it fit or no.’ When he dies, Aurora mourns. She then continues his work by seeking to educate herself. ‘But, after I had read for memory,/ I read for hope. The path my father’s foot/ Had trod me out…alone I carried on…’ And soon the reader accompanies her – as many another heroine – into that great symbol of the human mind, the attic:

Books, books, books!

I had found the secret of a garret-room

Piled high with cases in my father’s name,

Piled high, packed large, – where, creeping in and out

Among the giant fossils of my past,

Like some small nimble mouse between the ribs

Of a mastodon, I nibbled here and there

At this or that box, pulling through the gap,

In heats of terror, haste, victorious joy,

The first book first. And how I felt it beat

Under my pillow, in the morning’s dark,

An hour before the sun would let me read!

My books!

Just as the author once over-ruled her father’s strictures, to run away and marry the poet Robert Browning, so her heroine struggles past the grim reality of a ‘stone-dead father’ to overwrite his name on those boxes of books with her own.

How high were those cases stacked in Aurora Leigh’s dead father’s attic? ‘Piled high’ she says, and then to stress the spectacle, ‘piled high, packed large.’ They were the ‘giant fossils…of a mastodon’, she a mouse. The colossus, held in awe.

With an uncanny match of imagery, in her poem ‘The Colossus’ Sylvia Plath crawls ‘like an ant in mourning/ Over the weedy acres’ of her dead father’s brow, ‘To mend the immense skull-plates and clear/ The bald, white tumuli of your eyes.’ But less optimistic than Aurora, who wants the sun so she can read her books, for Plath the sun ‘rises under the pillar of your tongue./ My hours are married to a shadow.’

The Colossus and the Earthquake

The colossus of Rhodes is thought to have been one hundred and five feet high. Built in the image of the sun-god Helios, it stood guard at the harbour entrance for about sixty years until it was wrecked by an earthquake (nota bene, Rem Koolhaas). The remnants, including gigantic pieces of hand and limb, lay scattered around the site for centuries. Eventually they were sold as scrap and taken away, it is rumoured, by a train of nine hundred camels. Now, with nothing left, this flourish of ancient statistics must suffice to impress us.

Unless, of course, like the narrator of Thomas Mann’s monumental Doctor Faustus, you derive little pleasure from the consideration of that which is almost beyond human comprehension and ‘can see no reason to fall in the dust and adore the fifth power of a million’. You are not easy to impress. Perhaps you have never been physically knocked to the ground by your father’s bible, like Anthony Trollope was, or have your tooth hammered out with a brick-like nineteenth-century hardback of Homer, as in the case of Leigh Hunt. Or better still, because closer to the female experience which interests me, you pick up a copy of Elizabeth Smart’s novel, By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept and shake your head in disbelief.

Speaking of love, Smart declares, ‘there are no minor facts in life, there is only the one tremendous one.’ And speaking of her lover, she swoons. ‘When we lie near the swimming pool in the sun, he comes through the bamboo bushes like land emerging from chaos. But I am the land, and he is the face upon the waters. He is the moon upon the tides, the dew, the rain, all seeds and all the honey of love. My bones are crushed like the bamboo-trees. I am the earth the plants grow through. But when they sprout I also will be a god.’ Resistance or submission to grandeur, it seems, is a very personal matter.

Notice particularly how the giant man is made to share his stature with the woman, how through her (literal) conception of his powers, she bestows an equivalent divinity on them both.

Notice also how after that first vision, ‘land emerging from chaos,’ the colossus is dispersed, becoming a face, a moon, tides, rain, seeds.

The near-human fate of the colossus of Rhodes, its demise at age sixty and its diasporic dispersal touches us even now. And when the Delphic oracle advised against the rebuilding of this statue, it might have foreseen the manifold colossi that were still to be imagined, designed, conjured, feared, scaled, adored, and mourned – elsewhere than in Rhodes.

Ruins

In the late eighteenth-century Gothic novel, The Castle of Otranto, Horace Walpole tweaks his reader’s imagination with a helmet that is ‘an hundred times more large than any casque ever made for human being.’ Scattered throughout the text, and throughout the castle, are further pieces of giant: feet, swords, hands. Within the narrative these ominous fragments, strewn about, inspire terror, and as clues, decipherment.

What is the puzzle which Walpole needs so obtusely to address? The story begins with the solemnity of an ancient folk-tale. ‘Manfred, prince of Otranto, had one son and one daughter: the latter, a most beautiful virgin, aged eighteen, was called Matilda. Conrad, the son, was three years younger, a homely youth, sickly, and of no promising disposition; yet he was the darling of his father, who never showed any symptoms of affection to Matilda.’ And therein lies Matilda’s challenge.

The revelation of relevant facts, the heaping up of knowledge – and acknowledgement – is the main concern, the story’s main frustration. Manfred is not a true prince of Otranto and his investment in the continuation of his falsely acquired power is crushed when his son is struck down by that prophetic, hyperbolic helmet. Sudden and surreal, the helmet’s interjection into the narrative is a grand gesture, if we believe it, and a clumsy one, if we do not.

There follows a terrible entanglement of plot and sexual innuendo. The novel’s suspense exists largely in the characters’ dramatic and gymnastic powers of extrication from these knots. So too we watch Walpole and Manfred, author and protagonist, manoeuvre around the obvious consequence of the boy’s death: that daughters also deserve ‘symptoms of affection’, and that their lines of continuity are as viable as those of the story’s blundering, murdering men. Or more so. This is the apocalyptic message. Matilda dies and ‘a clap of thunder at that instant shook the castle to its foundations; the earth rocked, and the clank of more than mortal armour was heard…’

Walpole took the theme of father-daughter, male-female entitlement as far as he could. It is only fair to assume that in 1798 he and his readers would have had some trouble resolving these issues. The castle, an arena where men’s and women’s loyalties were tested, becomes a ‘woeful space’. Only ruins – and the vision of an avenging ancestral giant – remain. As Sylvia Plath complains to her dead father, ‘I shall never get you put together entirely,/ Pieced, glued, and properly jointed.’

Literature is a place of many such colossal figures, represented variously as flights of Icarus, the towering up of dark deeds in Hellenistic plays, or in Shakespeare, as flights of the imagination, flights of Gothic stairs, Faustian urges to immortality, and not least, the dominion of parents over children, particularly of fathers over daughters. Since it is at once the manifestation of a Freudian cliché and relatively unexplored critical territory, this insistence on giants – as people, ideas, desires, fears – in writing by and about women, has caught my attention.

Anonymous(e) to Famous(e)

A ‘little scrap from elsewhere’ (from Rhodes? from Otranto?) the French writer Hélène Cixous has called herself, not quite at home with any of the parts of her cultural composite: Algerian, French, German-Jewish, and Czech-Hungarian, Sephardic-Jewish, and Spanish, and English-American. To comprehend this fragmentation of her self, she tells how she was inspired to write. ‘Even though I was only a meagre anonymous mouse, I knew vividly the awful jolt that galvanises the prophet, wakened in mid-life by an order from above. It’s a force to make you cross oceans… And in my body the breath of a giant… Who’s changing me into a monster? Into a mouse wanting to swell to the size of a prophet?’ She writes of the mixture of terror and delight in being ‘lifted up one morning, snatched off the ground, swung in the air,’ what it feels like ‘to fall asleep a mouse and wake up an eagle!’

In 1992 I attended a series of seminars conducted by Hélène Cixous at the University of Virginia. During these sessions ‘the prophet’ worked herself into a meditative rapture over the ins and outs of what amounts to literary freemasonry. She spoke about secrets held close by the giants of the inner circle – Kafka, Joyce, Rilke – and about codes of guardianship or revelation.

(‘Perhaps you consider yourself an oracle,’ says Plath. ‘Mouthpiece of the dead, or of some god or other.’)

I remember she theorised at length, and with the aid of the blackboard – emphatically, the teacher – about doors and ladders and bridges, and other curious methods of approach to the poetic inner sanctum. She said she loved the letter H – in French it is an aspirated ‘hache’ – of her name, Hélène, as being a step of just such a ladder, or a bridge between two I(eye)s, to represent a multiplicity of selves.

In a trance of hysterical boredom, I saw a jest: monsters, prophets, eagles, mice, Plath-like ‘scaling little ladders with gluepots and pails of Lysol.’ And wondered if the aspiring H would soon pick up that other handle of her self – the hatchet or the axe – and wreak havoc. For she had once written: ‘One can emerge from death, I believe, only with an irrepressible burst of laughter. I laughed. I sat down at the top of a ladder whose rungs were covered with stained feathers, vestiges of defeated angels, very high above the ruins of Babylon…in my left hand my deaths, in my right hand my possible lives. If there was godliness, I was of it.’

No laughter here (unless she was chuckling to herself). From that vantage, it was a serious Cixous who dispensed the chaff of wisdom to her silent mouse-audience. We heard that she thought of books as her ‘parents-on-the-shelf’, that great authors write under the pseudonym of their readers, that writing was like learning to die.

At one point Cixous suggested that to participate in the bonded mystery of reading-writing, one must be prepared to lay aside one’s props, to shed one’s layers of identity. While she spoke, very slowly and casually so it was hardly possible to see it as theatrical deliberation – but I did – the prophet appeared to be demonstrating her commitment to literary abandonment. She took things off. First one watch, and after some time, another, laying them neatly side by side, Paris time, Charlottesville time. She wore two necklaces, two jackets. Several layers were thus removed, until an elegant Frenchwoman was transformed into a sexy, suntanned priestess of literature in black lace décolletage. Were Kafka, Joyce and Rilke watching? Were they pleased? The double meaning of her essay ‘Coming to Writing’ was disclosed. The sexuality of articulation took a leap.

I could not endure the oppressive drama of this one-woman show. I left after three hours of ecstatic monologue and striptease (and later heard it continued many hours more), angry to have been duped that long.

Hélène Cixous was gargantuan. Did we want to listen to her ‘eating, sucking, suckling, kissing’ texts? Hélène – haleine – whose breath seemed inexhaustible and in whose expansive verbal shadow the listener shrank: was she aware, I wondered, that her self-mythification and her magnitude depended on our subscription to the same ideals?

A Blue Sky out of the Oresteia Arches Above Us

In the course of seeking her own myth, Anaïs Nin writes of her relationship with her father. ‘I love him with the thousand divinatory eyes I want to be loved with. It is the disease of love, not the fruit. It is when one’s self has become so masked to the world, one’s language so unintelligible, one’s loneliness so consuming, that only one’s Double can penetrate one.’ She is fully conscious of her indulgence as abnormal or uncommon, the subject of social taboos and psychological investigation. Both she and her father know that their obsession with each other is an exaggeration of normal feelings. To the reader this is carried over into a dangerous game, at times a caricature, a Rabelaisian grotesque.

In that section of her diary now published as Incest, Nin seduces and is seduced by her father. At the height of their lovemaking, he finds the critical distance to see it as a ‘tragedy’ and the wit to wish Freud were a witness to the proceedings. The love scenes are described by Nin as primitive. ‘Worse than a barnyard’, as Plath might say. ‘A disturbing account’, notes Deirdre Bair, her biographer.

And yet the diary-account of what Bair calls those ‘nine days of unbridled sexuality’, seems controlled, designed, deliberately modern, an autobiographical experiment. Daughter and father unleash a brimming force which becomes even more thrilling for it being indulged, discussed, written down, thought through. In the spirit of the affair’s potential theatricality, Nin plays Electra to the full. Her father is King and their encounter offers an Oresteian sequel. The author – and we have the impression that between lovemaking she wrote furiously – performs a remarkable balancing act in which passion, humour, even farce (sadly missing from Cixous’s self-appointments) are at every moment only thinly removed from horror and shame. By taking risks and taking charge of the taboo, Nin lifts these episodes out of a purely indulgent raw confessional mode up into the literary domain.

As well as ‘king’, Anaïs Nin calls her lover-father ‘le Roi Soleil’ and ‘God’. She says, ‘my Father is nonhuman and should have been God…The ideal self exalted.’

In The Future of an Illusion Sigmund Freud traces the patterns of awe and terror which we draw between fathers, forces of nature, and divinity. He sees the religious self in adoration of God as an extension of an infantile prototype when one ‘found oneself in a similar state of helplessness: as a small child, in relation to one’s parents. One had reason to fear them, and especially one’s father; and yet one was sure of his protection against the dangers one knew.’

Within that Freudian paradigm, Anaïs Nin writes: ‘As a child I had the obscure terror that this man could never be satisfied. I wonder what this sense of my Father’s exactingness contributed to my haunting pursuit of perfection. I wonder what obscure awareness of his demands, expectations of life, moved me to the great efforts I made.’ She was greatly interested in psychoanalysis. By taking her father as lover she could, quite literally, meet his demands and so, as Freud suggested, could rob life of its terror, get even, the master’s mistress. Significantly, her writing-life began with an unsent letter to her father – and later, he expressed jealousy not of her many other lovers but of her diary.

Like Aurora Leigh, Nin is delighted to compare herself to her father, to count up their likenesses. She calls him her Double. She seems to wish to take the quest for masculine multiplication further still. She dreams of being ‘surrounded by men.’

Going Up

George Frederic Jones was six feet tall, and like the colossus of Rhodes he also died in his sixtieth year. To his young daughter, who was to become the novelist Edith Wharton, the head of this ‘tall handsome father…was so far aloft that when she walked beside him she was too near to see his face.’ In the case of the grown-up Edith, her biographer R.W.B. Lewis noted a tendency to surround herself with unmarried males. ‘There were to be several sets of this species, and probably a somewhat different reason may be assigned for Edith Wharton’s enjoyment of each in turn. But it was a basic fact that she drew more substance from the company of men than of women, and the more so if the men in question could give her their undivided attention.’

Of course, these Atlas-daughters satisfy a commonly accepted or expected paternal desire for filial admiration. Roald Dahl’s children’s classic, The BFG, is just such a tale of intimacy and inheritance, requited this time, between an eccentric giant and a human child, another orphan, called Sophie. The book is dedicated to the author’s daughter Olivia who died at the age of seven, ‘kidsnatched’, as the Big Friendly Giant would say, and thus always a child in the memory of her parent.

Cixous as a child imagined herself being carried around by God. ‘I lived in the left-hand pocket of his coat. Despite my tender age, I was his Pocket-Woman.’ Plath is similarly accommodated. ‘Nights, I squat in the cornucopia/ Of your left ear, out of the wind…’ And Sophie is transported both ways, in the pocket and the ear of the BFG.

He is a ‘dream-blowing giant’. He hunts for those ‘little wispy-misty bubbles [that are] searching for sleeping people.’ He finds and supplies what psychoanalysis buys and sells. How does he do it, Sophie wants to know. He is guided by his ‘enormous truck-wheel ears.’

‘’You is deaf as a dumpling compared with me!’ cried the BFG. ‘You is hearing only thumping loud noises with those little earwigs of yours. But I am hearing all the secret whisperings of the world!’’

The ‘secret whisperings of the world’ is what it is all about, I think. The giant-fathers appear to have an intimate knowledge of distant places, a privilege which the daughters would love to share. In her story ‘Postcards from Surfers’ Helen Garner remembers that same child’s perspective. ‘His big blunt hands used to fling out the fleeces, still warm, on to the greasy table. His hands looked as if they had no feeling in them but they teased out the wool, judged it, classed it, assigned it a fineness and a destination: Italy, Switzerland, Japan… We walked along Strachan Avenue, Manifold Heights, hand in hand. ‘Listen,’ he said. ‘Listen to the wind in the wires.’ I must have been very little then, for the wire were so high I can’t remember seeing them.’

As with Walpole’s Matilda, paternal criticism or rejection often heightens the intensity of the daughter’s needs. Garner has spoken of ‘unfinished business’ with her father, of a ‘difficult relationship’ which was to become the ‘chief drama’ of her life. This unresolved complexity, Garner suggests, is also the cause of her attraction to men ‘incapable of love’.

Manifold Heights

A colossus, then, is an extravagant fixture, a site around or over or in the light of which one wishes to move, to be seen to move. It is a fixture and a fixation, a grand projection: a Trojan horse, a tower of Babel, a Norse giant whose skull becomes the sky, the helmet of Otranto, the Frankenstein monster, Thomas Mann’s Adrian Leverkühn, skyscrapers, gravestones, an idea, a mountain, a passion, a painting, a book.

A colossus is something much, much bigger than one’s simple self. There is in some a huge capacity for admiration and aspiration, which amounts to a kind of connoisseurship of that ‘heaven-storming monumentality’ and ‘hypertrophied egocentrism’ which, as C.W. Ceram has pointed out, accounts for the building of very big objects, such as the pyramids.

If effective, sublime enthusiasm subsumes one’s subjectivity. Individuality disappears as one writes oneself large. The self is universalised. There is a kind of heroism in having details fall away. Thus Mann writes of his Faustian protagonist, ‘He did not love personal glances, he altogether refused to entertain them or respond to them…’

But a colossus is nothing if it is not perceived as such. Cixous shrinks if we take her self-appointed grandeur in jest. The mastodon’s magnificence depends on the enraptured imagination of the mouse. Thus at the very end of his poem of wide-eyed worship of Mont Blanc, P.B. Shelley coolly asks – ’And what were thou, and earth, and stars, and sea,/ If to the human mind’s imaginings/ Silence and solitude were vacancy?’

In utter solitude, and pregnant with the first of four children by the man who burst through the bamboo ‘like land emerging from chaos,’ Elizabeth Smart sits down at New York’s Grand Central Station and weeps. ‘The pain was unbearable, but I did not want it to end: It had operatic grandeur. It lit up Grand Central Station like a Judgement Day. It was more iron-muscled than Samson in his moment of revelation…my face floated away on that haemorrhage of sorrow that dissolved even the chromium-plating the glass palaces the concrete of New York.’

Same colossus, different angle.

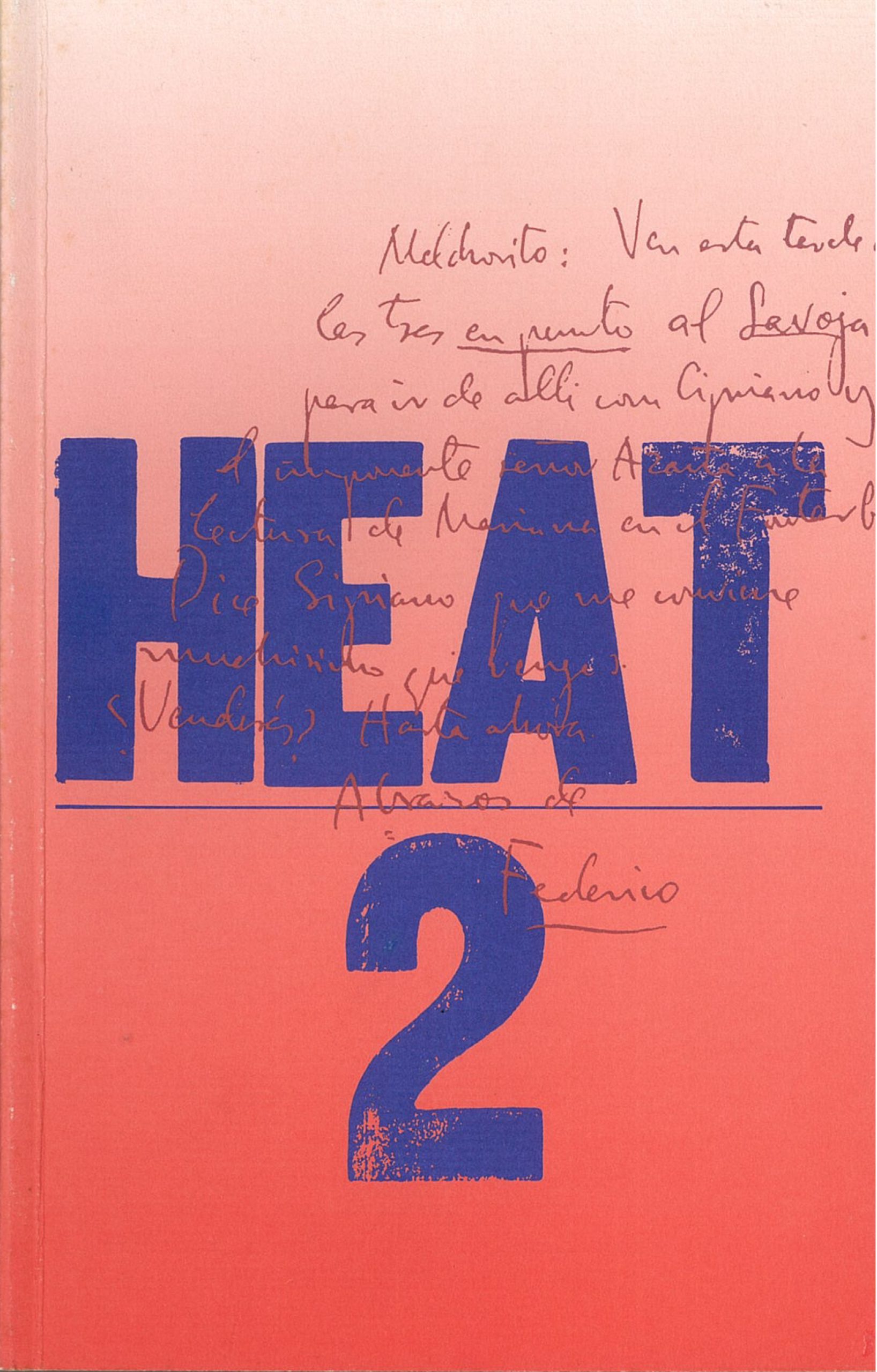

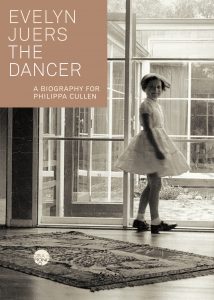

In this essay I refer to the following works, in order of citation: Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York (1978), Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), Charlotte Brontë, Villette (1853), Anna Elizabeth Blunden, ‘The Seamstress’ (oil on canvas, 1854), Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Aurora Leigh (1857), Sylvia Plath, ‘The Colossus’ (1959), Thomas Mann, Doctor Faustus (1947), Elizabeth Smart, By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept (1945), Horace Walpole, The Castle of Otranto (1765), Hélène Cixous, Coming to Writing (1991), Anaïs Nin, Incest (1932), Deirdre Bair, Anaïs Nin (1995), Edith Wharton, A Backward Glance (1934), R.W.B. Lewis, Edith Wharton (1975), Roald Dahl, The BFG (1982), Helen Garner, Postcards from Surfers (1985), Gillian Whitlock, Eight Voices of the Eighties (1989), C.W. Ceram, Gods, Graves and Scholars (1951), Percy Bysshe Shelley, ‘Mont Blanc’ (1816), Sigmund Freud, The Future of an Illusion (1927).