Catriona Menzies-Pike: a note on Open Secrets

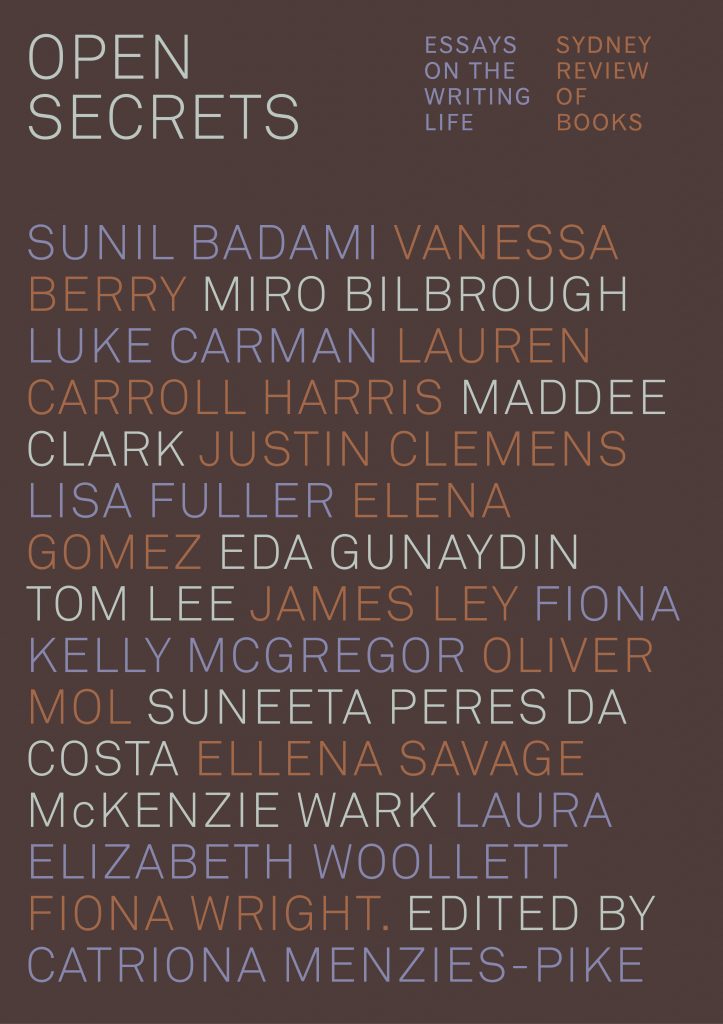

Open Secrets: Essays on the Writing Life is the new collection published by the Sydney Review of Books and edited by Catriona Menzies-Pike. The following, written by Menzies-Pike, is from the book’s introduction.

The first myth about literary work in Australia is that writers don’t actually do much of it. Debauched, unworldly, undeserving, lavished with more public money than they deserve – they enjoy a sinecure funded by taxpayers, for which privilege they are asked little in return. Read, write, lounge, scrounge. The second myth is that to be a writer is to have answered a divine call. If writing is a vocation, it’s hardly work. Do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life. Bit rich to expect to get paid. Yet the reckless bon vivant and the worthy ascetic actually have few living counterparts in the corps of contemporary Australian literature. Most Australian writers don’t get paid much for their work, not by publishers, not by readers, not by the government – which is hardly to say that they shouldn’t.

So how – and why – does the work get done in a world that measures value in dollars and widgets and accords so little to literature? How are writers made? And how is writing made? These were the prompts the Sydney Review of Books issued to all kinds of writers, to the essayists and critics who are frequent contributors to the journal, and to poets, novelists and experimental writers. We sought essays that charted writing as a form of creative labour, and found ourselves with a large and eclectic set of works that deliver new insights into the creation of Australian literature.

How writers get it done is a staple of festival Q&As and magazine profiles. There are no precious morning rituals here, however, no magic tricks for aspiring writers, and little in the way of idealism. These essays document writing lives defined as much by procrastination, distraction and economic precarity as by desire and imagination, by aesthetic and intellectual commitments. Labour is at the heart of this collection: creative labour, yes, but also the day jobs, side gigs, and care work that make space for writing. The public funding available to Australian writers continues to contract, the prospects of healthy royalties from book publication are dim, and the gigs on which so many relied to pay bills, workshops, teaching, public events, have diminished in number. There’s nothing in Open Secrets that conflicts with the regular reports from the Australian Society of Authors about the sinking financial returns of literary work. Many of the essays in this book, especially those authored during the Covid shutdowns in 2020 and 2021, are characterised by a discernible weariness.

Is it worth it? For readers, the work is the reward. As you’ll discover, these essays are funny and intelligent and they quiver with joy and determination. For the writers gathered in Open Secrets, however, the true worth of literary work is a complex question that generates often contradictory answers. Writers may work alone in their rooms, but they are also creatures of the world, and each contributor to Open Secrets thinks in surprising ways about literature; they attest to forms of value beyond the economic, to the social, political and aesthetic dimensions of literary practice. This book offers portholes into the places where writing happens and portals to the new worlds and ways of living it might create. These essays bear witness to the resilience required to commit to the writing life – and to the vital transformative possibilities of literature, for writers, for readers and our culture.