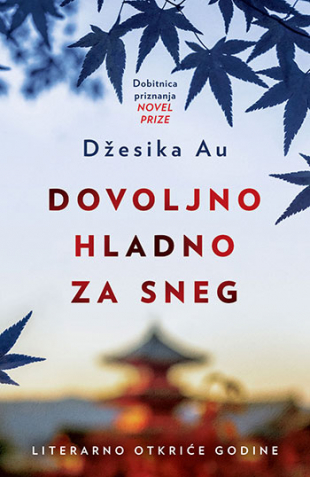

Jessica Au

Jessica Au wins Prime Minister’s Literary Award for Cold Enough for Snow

Jessica Au, author of Cold Enough for Snow, has won the 2023 Prime Minister’s Literary Award for Fiction. The announcement was made at a ceremony in November at the National Library of Australia in Canberra.

‘Prizes like these are always a particular blend of luck and happenstance, and I am truly grateful to whatever alchemy has allowed me to stand here tonight,’ said Au in her acceptance speech. ‘I know for sure none of it would be possible without The Novel Prize, without Giramondo, without your support.’

Read the judges’ comments for Cold Enough for Snow:

Cold Enough For Snow relates a short holiday spent together in Japan by a mother and daughter. They live in different countries and the daughter has made a meticulous itinerary, revealing Japan through its natural beauty and through the cultural galleries, houses, rooms, fabrics, places.

Japan itself, with an elaborate and exquisite surface and an elusive interior, is an intricate and sustained metaphor for the relationship between the mother and daughter. As they move through this unfamiliar, cultivated world their own internal lives unfurl. Surfaces are the touchstones in life as well as the place to begin.

The novel is a crystalline technical feat: a series of small portraits and wider scenes, with stillness achieved by capturing arrested motion. The novel is an enquiry into the human heart and how lives are led. Here is the daily embedded in the eternal: here we are in lives past, but also entirely present. Au, by some personal alchemy, uses image the way poets use compression of language. The same poetic is applied to her choice of words. The clarity of language suggests contemporary Korean novels and has an unusual gravity.

Au’s writing has a quietness, a sophistication of expression emerging from a hum of silence and thought. It signals a new direction in Australian literature, intricately structured and with a flow and reach that, like all remarkable writing, is without boundaries.

Cold Enough for Snow and Harvest Lingo shortlisted for Prime Minister’s Literary Awards

Jessica Au’s novel Cold Enough for Snow and Lionel Fogarty’s poetry collection Harvest Lingo have both been shortlisted for the 2023 Prime Minister’s Literary Awards. Each book is already the recipient of major Australian prizes in literature.

Fiction category: Judges’ comments, Cold Enough for Snow:

Cold Enough For Snow relates a short holiday spent together in Japan by a mother and daughter. They live in different countries and the daughter has made a meticulous itinerary, revealing Japan through its natural beauty and through the cultural galleries, houses, rooms, fabrics, places.

Japan itself, with an elaborate and exquisite surface and an elusive interior, is an intricate and sustained metaphor for the relationship between the mother and daughter. As they move through this unfamiliar, cultivated world their own internal lives unfurl. Surfaces are the touchstones in life as well as the place to begin.

The novel is a crystalline technical feat: a series of small portraits and wider scenes, with stillness achieved by capturing arrested motion. The novel is an enquiry into the human heart and how lives are led. Here is the daily embedded in the eternal: here we are in lives past, but also entirely present. Au, by some personal alchemy, uses image the way poets use compression of language. The same poetic is applied to her choice of words. The clarity of language suggests contemporary Korean novels and has an unusual gravity.

Au’s writing has a quietness, a sophistication of expression emerging from a hum of silence and thought. It signals a new direction in Australian literature, intricately structured and with a flow and reach that, like all remarkable writing, is without boundaries.

Poetry category: Judges’ comments, Harvest Lingo

In this powerful new collection, Lionel Fogarty demonstrates that his many decades of writing and publishing poetry have not diminished his political bite or poetic power. Across themes of love and Country, domestic and international politics, the personal and interpersonal, Fogarty does not shy away from interrogating all facets of life as observed and experienced by an Indigenous Elder and a life-long activist.

Often, with the sense of an outsider or ‘intruder’, Fogarty has created a collection that is dense and multilayered, veering into abstraction that intensely evokes the absurd realities that Indigenous people are asked to face living in colonial Australia.

Fogarty writes with a radical inversion of the English language that turns the coloniser’s tongue in upon itself to create poetry that challenges the reader in pursuit of political liberation. His work is singular and uncompromising, it is often difficult, but it has a lyrical form and a syntactical uniqueness that flows with rhythm and purpose. Harvest Lingo is a book of intense commitment and power.

The winners will be announced on Thursday 16 November at the National Library of Australia in Canberra.

Aitken, Au, Fogarty and Gorton shortlisted for the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards

Three Giramondo poets and one novelist have been shortlisted for the 2023 NSW Premier’s Literary Awards. The shortlisted works:

Revenants by Adam Aitken – Poetry Award

Cold Enough for Snow by Jessica Au – Fiction Award

Harvest Lingo by Lionel Fogarty – Indigenous Writer’s Prize

Mirabilia by Lisa Gorton – Poetry Award

Read the judges’ comments below. Congratulations to these authors, and to all of this year’s finalists.

Revenants by Adam Aitken

Shortlisted for the Kenneth Slessor Prize for Poetry

Revenants is a mesmerising collection of wistful, atmospheric poems that speak of returnings and revisitations, of the impossible desire to embody and inhabit the past. The poet guides us through places, people and events which no longer exist, but have left their indelible shadows on this earth. Aitken questions what it means to be haunted, and seamlessly juxtaposes the prosaic with the poetic, at times self-consciously subverting the artistic impulse with wry humour.

With characteristic gentleness and a deft lightness of touch, Aitken displays his restless curiosity and probing intelligence throughout the poems, all the while dancing upon strange currents of longing, loneliness and resignation. Throughout the collection, Revenants reiterates the questions that underpin our meaning-making in this world: What does it mean to be alive? What does it mean to be dead? ‘We enter this room / and all stop talking. / Maybe it’s like this / beyond the canvas’.

— Judges’ comments

Cold Enough for Snow by Jessica Au

Shortlisted for the Christina Stead Prize for Fiction

Vote for the book in the NSWPLA People’s Choice Awards here. Voting closes 14 April 2023.

A masterpiece of observation and subtle insight, this exquisite novel uses crisp prose and the deceptive simplicity of its narrative to bring intimate relationships to shimmering life. A daughter and mother meet for a holiday in Japan. The narrator-daughter observes her mother as they wander through the streets of Tokyo, into galleries, temples and shops, and into tentative conversations that evoke their shared and separate and sometimes imagined experiences.

As each deftly rendered episode flows onto the next, a meditation emerges on the elusive, shifting web of meaning made by stories, memories and images in our lives. Deeply felt and brilliantly restrained, this book conveys the often-contradictory dynamics in the parent–child relationship, the way in which both alienation and intimacy, and difference and resonance, shape the relationships between the narrator and her mother, and the narrator with herself.

— Judges’ comments

Harvest Lingo by Lionel Fogarty

Shortlisted for the Indigenous Writers’ Prize

This extraordinary volume of poetry from renowned Yugambeh poet Lionel Fogarty is urgent, poignant and compelling. It reckons with history, interconnectedness and injustice, interweaving individual experience with the larger webs of relationships that link First Nations peoples to each other whilst also speaking to connections with colonised peoples elsewhere. Throughout, Fogarty interrogates expression and form, wielding the English language itself as a decolonising tool. The poet challenges empire while portraying the lives and experiences of First Nations peoples with intimacy and grace.

Harvest Lingo invites the reader into dialogues that stretch across time, space, and place. This collection is uncompromising in its demand that the voices of First Nations peoples, communities and Countries be heard on our own terms. Every carefully chosen word connects with others to form a rhythm that is sometimes gentle and sometimes fierce, mirroring the heartbeats of peoples, place and resistance that shape this collection.

— Judges’ comments

Mirabilia by Lisa Gorton

Shortlisted for the Kenneth Slessor Prize for Poetry

Mirabilia’s poems stem from deep, eclectic research. As they unpick and anatomise ekphrastic practices (sometimes gutting them), they are propelled by a powerful interest in justice, especially concerning women’s lives and the more-than-human world. The poems’ method involves looking again, assembling evidence in patterns so that poems speak to one another. Lines and images bounce between poems, repositioned, restive. These astounding poems unfold like the chambers of a nautilus: spiralling, repeating in dazzling patterns.

An eye/I hovers but is brought into question for its complicity in ways of seeing that have cramped or violated the lives and conditions Gorton explores. This eye/I is unsettled, elided, displaced, mirrored and measured. Gorton’s intelligent and inventive poems dwell between the lines of history, art and poetry, cerebral, mysterious and often devastating. They bring to poetry a heteroglossia usually confined to fiction in their exhilarating consideration of how art might be made and unmade.

— Judges’ comments

Jessica Au wins Victorian Prize for Literature for Cold Enough for Snow

Melbourne author Jessica Au has won both the Victorian Prize for Literature (worth $100,000) and the Fiction award (worth $25,000) at the 2023 Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards for her novel Cold Enough for Snow. The former is the country’s richest literary prize.

The announcement was made at a ceremony on 2 February 2023 at Melbourne’s Federation Square. (See the moment that Cold Enough for Snow won the night’s major prize.) It came just a few days after the book was longlisted for the Dublin Literary Award, the world’s most valuable annual prize for a single work of fiction published in English.

In her acceptance speech, Au described her win as a ‘life-changing moment.’

‘Prizes, they do fade – you’re left with ordinary life and ordinary time. And that’s just time to think and time to read and time to be. And for me it’s time to stare deeply into the eyes of my cat. And maybe if we’re lucky, out of that time some writing comes – and that’s when you can say all the things that are impossible to say in speeches like this.’

In an interview with the Sydney Morning Herald, Au named Rachel Cusk as an influence. ‘I really respect prose that is very clear and direct,’ she told the paper. ‘There’s something in me that likes prose that you can’t really hide behind.’

Listen to Au speak with ABC Radio National the morning after the announcement.

Jessica Au was the inaugural recipient of The Novel Prize, a prize for unpublished manuscripts that ‘explore and expand the possibilities of the form, and are innovative and imaginative in style’. Since it was published in early 2021, Au’s novel has received widespread international acclaim, with rights sold in eighteen territories.

Giramondo congratulates Au, and all the other Victorian Premier’s Literary Award winners and finalists.

Lionel Fogarty and Jessica Au shortlisted for 2023 Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards

Works by Jessica Au and Lionel Fogarty have been shortlisted for the 2023 Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards. Au has been nominated in the Fiction category for her novel Cold Enough for Snow, and Fogarty has been nominated in the Indigenous Writing category for his poetry collection, Harvest Lingo. Read the judges’s comments below.

Lionel Fogarty’s anthology of poems covers an enormous breadth of subject matter, marrying humanistic compassion and intelligence with remarkable formal experimentation. Topics covered by the poems include international terrorism, the Internet, medicine, and Emiliano Zapata, but Fogarty brilliantly collapses categories and gives a true sense of the interrelatedness of phenomena. Particularly striking are the ‘India Poems’, which form the second part of the anthology and discuss the Indian caste system and economic inequality in relationship with the position of Australia’s First Peoples. The poems emphasise revolution as a global movement and the need to cross territorial boundaries; at the same time, they contain achingly personal and poignant reflections on death, desire, and memory. The style of the poems is intellectually and aesthetically challenging without being abstruse. Fogarty often defies easy interpretation, but never retreats into obscurantism. Some lines strike the reader as a blinding flash of insight: ‘Fascism is the dead flower for every dead voice’.

Above all, Harvest Lingo presents a truly unique poetic vision. Despite the diversity of the poems, there is a consistent sense throughout that political struggle without love is ultimately futile. As Fogarty writes in ‘Stay Alive Next 16 Years (Fish Trap)’: ‘We don’t want desire to be dead leaves.’ It is rare to encounter a book which operates so effortlessly on the intellectual, poetic, and political registers.

— Judges’ report, Harvest Lingo

Jessica Au’s lyrical second novel, Cold Enough for Snow, opens up new horizons for Australian literature. Featuring an unnamed protagonist travelling with her mother in Japan, Au’s work gently poses the question: how well can we know the ones we love? Masterfully slipping between memory and the present, the novel carries a subtle eloquence, replete with astute observations. Au’s prose is like a river, pulling the reader along as the story pools and eddies, flowing steady and deep. It may be a slender volume – but this book holds all the heft of a writer in full command of her craft.

— Judges’ report, Cold Enough for Snow

‘Can we truly know another’s inner world?’ – Jessica Au on Cold Enough for Snow

Since its publication in the Australia, the United States and United Kingdom upon winning The Novel Prize, Jessica Au’s Cold Enough for Snow has been published in numerous countries, with translation into eighteen languages.

In July 2022, the book was published by Serbian publishing house Laguna, who asked her to comment on Cold Enough for Snow’s genesis and themes. Read their interview with Au below.

How did Cold Enough for Snow become a novel? What did you initially want to tell with this book?

Like many things, it became a novel slowly over time. The first iteration was a short story that I wrote ten years ago about a mother and daughter travelling to Tokyo. After that, I tried to work on other things, thinking I might get a collection together, however none of those pieces felt ‘alive’ in the way of that one short story. So I returned to it after several years and tried to work on it. In using the journey between the mother and daughter as a container, many of the other things I had been thinking on – being a young woman in the world, or feeling connected to art and literature without necessarily feeling like an artist – began to find their way in, making up many of the digressions into memory that ended up in the book.

I don’t know if I wanted to tell anything at the outset – so much of writing is intuitive – but looking back, I can see that one of the driving questions in the book is about distance. It is relatively common for families to have within them some points of divergence, which could be anything from class to education, or culture, place of birth and language, or personality and character. But I wanted to ask what happens when, due to the speed of migration, all of those things end up being present in a single relationship? There was this gap, paired with the fact that children can know their parents very intimately.

Where did the story take you during the writing? What did you learn about yourself and the world around you while writing this novel?

Rather than necessarily taking you anywhere definitive, I think that writing allows you to dwell in spaces longer than ordinary time permits, and sometimes this working-through and holding can be a form of catharsis, though not always a source of change.

I think I was trying to understand how things come to be and to do so in a way that felt true to me. So much of what I had read about the nature of diaspora, of distance, didn’t seem to really match the lived experience of it: the confusion, the sense of incompleteness, paired with closeness and nostalgia. (It’s not that there aren’t writers out there who have done and are doing this, but for much of my childhood, this was undiscoverable for me). So I was trying to define, rather than be defined, to reconcile my inner world with the outward one. Perhaps if I learnt one thing, it was that the experience of migration, even though it can be perceived as fragmented and discontinuous, and was once looked down upon, can in fact be a rich, generative thing, a thing of literature.

Who are the mother and daughter in your story? Why was it important for you to tell their story through a novel that does not have a specific plot, but rather a novel of atmosphere?

They are characters who represent, at different times, parts of myself, parts of my family, and parts of the questions of life and literature.

On plot, I’ve always been unable to write this because in a way I don’t feel that’s how life happens. Or rather, if a dramatic event occurs, then this too is often punctuated by boredom, by everyday tasks or wandering thoughts. Conversely, I also think that so much of life – the things that really affect us – actually happen in these small, almost unspeakable moments, deeply felt but not always fully conscious. You can’t always parse this at the time but they may return to you later, and are formative.

Whether we have the right to truly know the inner world of another person, even when it comes to our closest ones, is one of the key questions of your book. What was the answer after writing?

Maybe I would phrase the question as: can we truly know another’s inner world? I think that to really know another, and to know ourselves completely is impossible, in part because nothing is fixed or singular. Yet there is still something worthwhile in the attempt. Writing, and by correlation reading, is really an act of understanding, and thus is perhaps the first step towards empathy; it is as close as we can hope to get to experiencing another consciousness.

You raise a number of other questions with this book – the question of identity, closeness, differences between generations, differences in origin… How difficult was it for you to fit all that into the story? Which of these questions was most important to you?

It was more generative than difficult in that I felt that all these things were interrelated and spoke to each other. In that sense too, I couldn’t put one about the other. Words like ‘identity’ or ‘belonging’ or ‘home’ can be useful in some contexts, but they are also such large, abstract nouns that don’t necessarily convey or capture the complexities or nuances of simply being a person in the world. Thus who the narrator is as a woman, her experiences and her education, are all deeply connected to her questions about family and heritage.

For example, in one digression, the narrator thinks back to her time at university, studying the Greek classics, a place that she has gained entrance to in part due to her mother’s work. It is in some ways an enlightening, vital place. It frees something in her. On the other hand, her knowledge also comes at a cost, because in studying philosophy or criticism or theory, she suddenly comes to understand her mother as a figure in history, and the impacts of colonial thinking, of domestic work and of motherhood on her. And this is linked to understanding her mother’s suffering in earlier life, of how others might see her.

The title Cold Enough for Snow is very striking. How did you choose this title? Does it also suggest the nature of the mother-daughter relationship? As much as they seem to know each other, there are many moments when it seems like they are strangers to each other.

I didn’t have the title till very near the end of writing. One early working title was A Common Language, which was taken from The Dream of a Common Language by the poet Adrienne Rich, which I think does express something of the desire for connection between the mother and daughter, as well as the impossibility of it.

What I liked about Cold Enough for Snow was its abstract, unfinished quality – that it could be both a fragment and a question, that it could relate to either time or place. I also liked the temporal element – snow comes only when the conditions are right, and when it does, it can be beautiful, almost magical, but it will also all disappear. And it is one of only a few questions that the mother asks in the book.

How did you feel when you received The Novel Prize? What does it mean to you personally, and what does it mean to the book?

It was a shock and was, and continues to be, a huge honour. I had admired all three publishers – Giramondo, Fitzcarraldo Editions and New Directions – for so long. It was a dream and a privilege to get the chance to work with them, and proved to be a wonderful experience: kind, thoughtful and stimulating. The Novel Prize I think opened up opportunities that the book would never have had, not in the least the chance to be translated with publishers like Laguna. At the same time, life also continues very ordinarily outside of prizes.

The portrayal of the relationship between life and art is also important to Cold Enough for Snow. What is art for you?

Sometimes it’s a way to try and preserve or keep in touch with a mood or feeling, to be reminded of a way of being outside the concerns of capitalism and work. This doesn’t always happen, but it’s something I try to look for if I can.

In the novel, I was also interested in the idea of art trying to depict life, while at the same time of us trying constantly to understand life through art – that circular, recursive relationship. In a similar way, I was also thinking about ekphrasis, and metaphoric thinking. Why is it that we seem to need a ‘third thing’, whether that is dance, music, a painting, a novel, to try and understand something? It strikes me that there is something about life that is complex and inarticulate and perhaps the only way to get close to the truth of it is to write around it, or to look at it obliquely.

Which writers, which books inspire you?

Mavis Gallant and Tove Ditlevsen for the cleanliness and seriousness of their sentences, and the way they speak of being both a woman and a writer in the world. Annie Ernaux, Édouard Louis and Simone de Beauvoir, especially for their books I Remain in Darkness, Who Killed My Father and A Very Easy Death respectively, which try to understand parents as products in history to whom we are intimately bonded. Jhumpa Lahiri, V S Naipaul and Yiyun Li for the ways in which they write about diaspora and exile. Natsume Sōseki, Yasunari Kawabata and Junichiro Tanizaki for their indirect style that makes you pay close attention to all that occurs beneath the surface. And of course, Rachel Cusk.

What does a writer’s day look like?

I rarely manage to do this, but my ideal day would be some mixture of routine, physicality and solitude. Periods of writing and meandering, and at some point a swim at the pool or a run. I have a small, narrow room, a sunroom, where I can work, and where my cat sits at the window. I love, most of all, the days when I rarely need to leave the apartment, when I can do small domestic tasks while simply thinking and being quiet.

In one of your interviews, you said that you lived in Europe for a while, including Sarajevo. What impressions do you have from Sarajevo, how did life there affect you and your writing?

We travelled around Europe for about nine months, and three of those were spent in Sarajevo. I have truly incredible memories of that time – the valley, the river, the surrounding mountains, hearing the call to prayer in the evenings, the markets, the architecture, burek and pomegranate juice… These I think are linked both to the beauty of the city, as well as to the feeling of being young and travelling. From there, we travelled to Belgrade, Zagreb, Dubrovnik, Budapest and so many other places. But it was in Sarajevo that I first wrote the short story that was the early version of Cold Enough for Snow.

Cold Enough for Snow by Jessica Au wins the 2022 Readings Prize for Fiction

Jessica Au’s Cold Enough for Snow is the 2022 winner of the Readings Prize for New Australian Fiction.

The announcement was made at a ceremony at Readings Emporium in Melbourne on Wednesday 26 October 2022.

‘Cold Enough for Snow was ten years in the making and, during that time, being in the world of independent bookshops and talking to booksellers was one of the best literary educations I could have asked for,’ said Au upon receiving the news. ‘I was so humbled even to be part of this year’s shortlist alongside such incredible authors. My gratitude to Readings staff for their irreplaceable knowledge, and to the judges of this year’s prize.’

In their report, the judging panel said of the work: ‘It was a difficult decision to choose one title from this list. The judging panel reflected on, rather than judged, how each title gave us a new insight into our humanity. To that end, Jessica Au’s quiet contemplative prose about a mother and a daughter traveling was considered the needed juxtaposition to the past year.’

Au’s book is the inaugural winner of The Novel Prize, which saw her manuscript selected from hundreds of international submissions and published by three publishers in three continents: Giramondo Publishing (AU), New Directions (UK) and Fitzcarraldo (UK). The book has since been shortlisted for numerous awards and translated into 18 languages and counting.

The judges of the 2022 Readings New Australian Fiction Prize were Christine Gordon (head of community engagement and programming and chair of judges), Carolyn Watson (Readings Doncaster), Susan Stevenson (Readings Malvern), Tye Cattanach (former schools and libraries specialist) and last year’s winner, Andrew Pippos (Lucky’s).