‘Can we truly know another’s inner world?’ – Jessica Au on Cold Enough for Snow

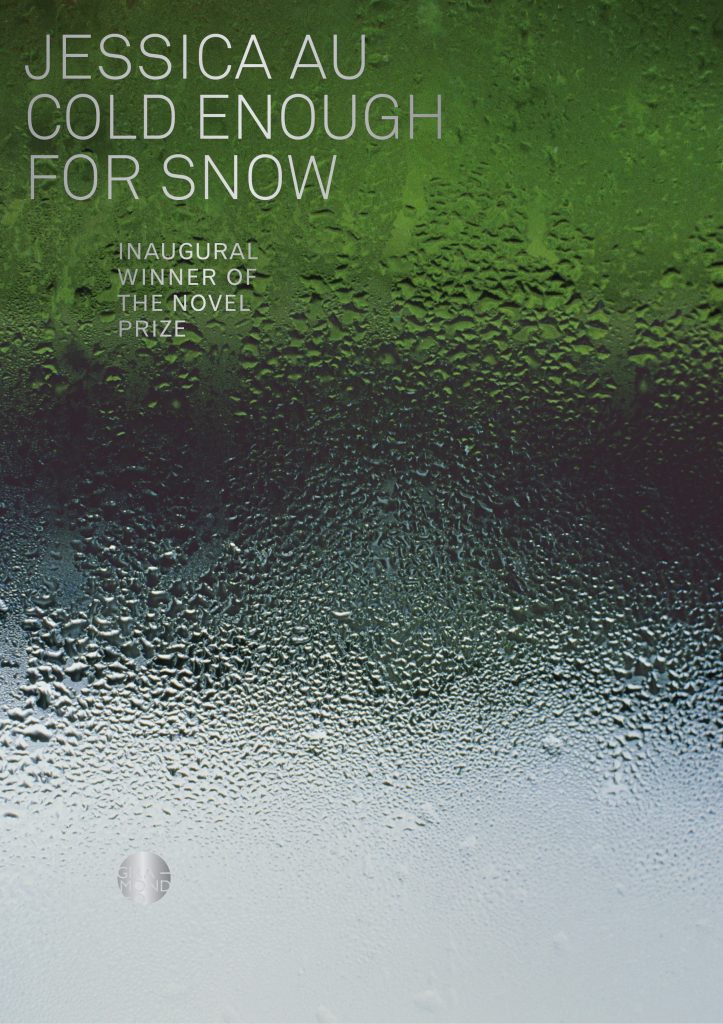

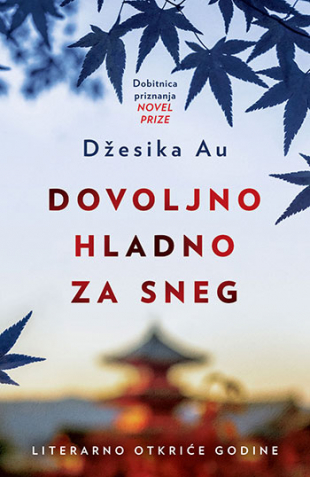

Since its publication in the Australia, the United States and United Kingdom upon winning The Novel Prize, Jessica Au’s Cold Enough for Snow has been published in numerous countries, with translation into eighteen languages.

In July 2022, the book was published by Serbian publishing house Laguna, who asked her to comment on Cold Enough for Snow’s genesis and themes. Read their interview with Au below.

How did Cold Enough for Snow become a novel? What did you initially want to tell with this book?

Like many things, it became a novel slowly over time. The first iteration was a short story that I wrote ten years ago about a mother and daughter travelling to Tokyo. After that, I tried to work on other things, thinking I might get a collection together, however none of those pieces felt ‘alive’ in the way of that one short story. So I returned to it after several years and tried to work on it. In using the journey between the mother and daughter as a container, many of the other things I had been thinking on – being a young woman in the world, or feeling connected to art and literature without necessarily feeling like an artist – began to find their way in, making up many of the digressions into memory that ended up in the book.

I don’t know if I wanted to tell anything at the outset – so much of writing is intuitive – but looking back, I can see that one of the driving questions in the book is about distance. It is relatively common for families to have within them some points of divergence, which could be anything from class to education, or culture, place of birth and language, or personality and character. But I wanted to ask what happens when, due to the speed of migration, all of those things end up being present in a single relationship? There was this gap, paired with the fact that children can know their parents very intimately.

Where did the story take you during the writing? What did you learn about yourself and the world around you while writing this novel?

Rather than necessarily taking you anywhere definitive, I think that writing allows you to dwell in spaces longer than ordinary time permits, and sometimes this working-through and holding can be a form of catharsis, though not always a source of change.

I think I was trying to understand how things come to be and to do so in a way that felt true to me. So much of what I had read about the nature of diaspora, of distance, didn’t seem to really match the lived experience of it: the confusion, the sense of incompleteness, paired with closeness and nostalgia. (It’s not that there aren’t writers out there who have done and are doing this, but for much of my childhood, this was undiscoverable for me). So I was trying to define, rather than be defined, to reconcile my inner world with the outward one. Perhaps if I learnt one thing, it was that the experience of migration, even though it can be perceived as fragmented and discontinuous, and was once looked down upon, can in fact be a rich, generative thing, a thing of literature.

Who are the mother and daughter in your story? Why was it important for you to tell their story through a novel that does not have a specific plot, but rather a novel of atmosphere?

They are characters who represent, at different times, parts of myself, parts of my family, and parts of the questions of life and literature.

On plot, I’ve always been unable to write this because in a way I don’t feel that’s how life happens. Or rather, if a dramatic event occurs, then this too is often punctuated by boredom, by everyday tasks or wandering thoughts. Conversely, I also think that so much of life – the things that really affect us – actually happen in these small, almost unspeakable moments, deeply felt but not always fully conscious. You can’t always parse this at the time but they may return to you later, and are formative.

Whether we have the right to truly know the inner world of another person, even when it comes to our closest ones, is one of the key questions of your book. What was the answer after writing?

Maybe I would phrase the question as: can we truly know another’s inner world? I think that to really know another, and to know ourselves completely is impossible, in part because nothing is fixed or singular. Yet there is still something worthwhile in the attempt. Writing, and by correlation reading, is really an act of understanding, and thus is perhaps the first step towards empathy; it is as close as we can hope to get to experiencing another consciousness.

You raise a number of other questions with this book – the question of identity, closeness, differences between generations, differences in origin… How difficult was it for you to fit all that into the story? Which of these questions was most important to you?

It was more generative than difficult in that I felt that all these things were interrelated and spoke to each other. In that sense too, I couldn’t put one about the other. Words like ‘identity’ or ‘belonging’ or ‘home’ can be useful in some contexts, but they are also such large, abstract nouns that don’t necessarily convey or capture the complexities or nuances of simply being a person in the world. Thus who the narrator is as a woman, her experiences and her education, are all deeply connected to her questions about family and heritage.

For example, in one digression, the narrator thinks back to her time at university, studying the Greek classics, a place that she has gained entrance to in part due to her mother’s work. It is in some ways an enlightening, vital place. It frees something in her. On the other hand, her knowledge also comes at a cost, because in studying philosophy or criticism or theory, she suddenly comes to understand her mother as a figure in history, and the impacts of colonial thinking, of domestic work and of motherhood on her. And this is linked to understanding her mother’s suffering in earlier life, of how others might see her.

The title Cold Enough for Snow is very striking. How did you choose this title? Does it also suggest the nature of the mother-daughter relationship? As much as they seem to know each other, there are many moments when it seems like they are strangers to each other.

I didn’t have the title till very near the end of writing. One early working title was A Common Language, which was taken from The Dream of a Common Language by the poet Adrienne Rich, which I think does express something of the desire for connection between the mother and daughter, as well as the impossibility of it.

What I liked about Cold Enough for Snow was its abstract, unfinished quality – that it could be both a fragment and a question, that it could relate to either time or place. I also liked the temporal element – snow comes only when the conditions are right, and when it does, it can be beautiful, almost magical, but it will also all disappear. And it is one of only a few questions that the mother asks in the book.

How did you feel when you received The Novel Prize? What does it mean to you personally, and what does it mean to the book?

It was a shock and was, and continues to be, a huge honour. I had admired all three publishers – Giramondo, Fitzcarraldo Editions and New Directions – for so long. It was a dream and a privilege to get the chance to work with them, and proved to be a wonderful experience: kind, thoughtful and stimulating. The Novel Prize I think opened up opportunities that the book would never have had, not in the least the chance to be translated with publishers like Laguna. At the same time, life also continues very ordinarily outside of prizes.

The portrayal of the relationship between life and art is also important to Cold Enough for Snow. What is art for you?

Sometimes it’s a way to try and preserve or keep in touch with a mood or feeling, to be reminded of a way of being outside the concerns of capitalism and work. This doesn’t always happen, but it’s something I try to look for if I can.

In the novel, I was also interested in the idea of art trying to depict life, while at the same time of us trying constantly to understand life through art – that circular, recursive relationship. In a similar way, I was also thinking about ekphrasis, and metaphoric thinking. Why is it that we seem to need a ‘third thing’, whether that is dance, music, a painting, a novel, to try and understand something? It strikes me that there is something about life that is complex and inarticulate and perhaps the only way to get close to the truth of it is to write around it, or to look at it obliquely.

Which writers, which books inspire you?

Mavis Gallant and Tove Ditlevsen for the cleanliness and seriousness of their sentences, and the way they speak of being both a woman and a writer in the world. Annie Ernaux, Édouard Louis and Simone de Beauvoir, especially for their books I Remain in Darkness, Who Killed My Father and A Very Easy Death respectively, which try to understand parents as products in history to whom we are intimately bonded. Jhumpa Lahiri, V S Naipaul and Yiyun Li for the ways in which they write about diaspora and exile. Natsume Sōseki, Yasunari Kawabata and Junichiro Tanizaki for their indirect style that makes you pay close attention to all that occurs beneath the surface. And of course, Rachel Cusk.

What does a writer’s day look like?

I rarely manage to do this, but my ideal day would be some mixture of routine, physicality and solitude. Periods of writing and meandering, and at some point a swim at the pool or a run. I have a small, narrow room, a sunroom, where I can work, and where my cat sits at the window. I love, most of all, the days when I rarely need to leave the apartment, when I can do small domestic tasks while simply thinking and being quiet.

In one of your interviews, you said that you lived in Europe for a while, including Sarajevo. What impressions do you have from Sarajevo, how did life there affect you and your writing?

We travelled around Europe for about nine months, and three of those were spent in Sarajevo. I have truly incredible memories of that time – the valley, the river, the surrounding mountains, hearing the call to prayer in the evenings, the markets, the architecture, burek and pomegranate juice… These I think are linked both to the beauty of the city, as well as to the feeling of being young and travelling. From there, we travelled to Belgrade, Zagreb, Dubrovnik, Budapest and so many other places. But it was in Sarajevo that I first wrote the short story that was the early version of Cold Enough for Snow.