Author:

Read the first pages of Xi Xi’s Mourning a Breast (trans. Jennifer Feeley)

Read the preface to Mourning a Breast, a multi-genre, auto-fictional work in which the cult Hong Kong writer Xi Xi (1937–2022) tries to make sense of her experiences with breast cancer – of diagnosis, illness and treatment. First released in China in 1992, it is published in English for the first time with translation by Jennifer Feeley.

Dear reader, when you open this book, are you standing in a bookstore? You’ve come to the bookstore today to have a look around and see if there are any books that pique your interest. You stumble upon Mourning a Breast – hey, what’s this book about? There’s no one around, so you casually pick it up. Out of all the books here, you just happen to flip through the one titled Mourning a Breast. Is it the word ‘breast’ that grabs your attention, though you feign otherwise? At this very moment, when you think of breasts, what comes to mind?

This is a book about breasts. Breasts are the subject matter, though I suppose the content may be rather different from what you’re envisioning. More than two and a half years ago, on a bright summer day, after this narrator had been swimming without a care in the world, she stood in the shower of the pool changing room and found a small lump in her breast, no bigger than a peanut. Soon after, it was confirmed to be breast cancer. This book tells the story of losing a breast. There are no melodramatic or sensationalist characters or plot twists. If this isn’t the book you’re looking for, carry on and good luck. However, I don’t intend to lose you, reader, so come on, why not buy a copy of Mourning a Breast while you’re at it, since on many levels, you and this book are actually quite closely connected? Are you a woman? May I ask how old you are? Please forgive me for being so presumptuous. Regardless of your age, the very fact that you can read these words is enough for you to be at risk for breast cancer. Let me put it this way: You’re just like the narrator of this book, living freely and happily in the world. There’s so much you’ve yet to do. The world is your oyster. Yet you’re completely unaware that there’s a tiny alien taking shape inside of you, scheming to supplant and devour you. That’s the demon known as cancer.

The twentieth century is coming to an end. In this era of cutting-edge science and technology, cancer is growing more and more rampant. The number of people suffering from cancer is steadily increasing, while patients’ ages are dropping to alarming lows. Are you a teenager in school? You say: I’m only sixteen – what do I have to worry about? Well, let me tell you, last year I came to know a breast cancer patient who was only twelve years old. Breast cancer is unpredictable. By the time you discover it, it’s likely that a tumour has already formed, leaving you with no choice but to part with the breasts that we women hold dear, and from then on, there’s no escaping death’s shadow. However, breast cancer is still considered one of the most fortunate forms of cancer, as it exhibits clear signs, can be surgically removed, and is also preventable. Eating well works wonders, and thanks to the miracle of modern medicine, we can keep on living for a considerably long time. Mourning a Breast aims to discuss precisely these matters and was written to help you – not from an expert’s viewpoint but from the perspective of a patient sharing her course of treatment, along with assorted reflections on her illness. A while back, a long-lost friend came across some selections from this book that had been published here and there. She started examining her own body, and lo and behold, she found that she also had breast cancer. Luckily, it was detected early; time is of the essence in treating this type of disease. If after reading this book, you begin taking better care of your health and paying attention to the various signals your body emits, then it won’t have been written in vain.

Of course, I hope you won’t get sick. Though birth, aging, illness and death are inevitable for everyone, I don’t want you ever to have to deal with cancer. Yet as the median age of the population increases, and the earth is desecrated day after day, we must psychologically prepare for the worst. Your elderly grandmother, mother, sister, friend or colleague could get cancer. If such an unfortunate turn of events were to occur, what would you do? Sever ties with them because you’re scared? Or lend a hand in the face of hardship? Mourning a Breast also touches upon these issues. Sick people don’t need your pity, but your concern and assistance can give them emotional comfort and help support their fight against the disease.

From another angle, disclosing the disease is also a form of self-healing for patients. The Chinese have always been a people who are secretive about sickness and hesitant to seek medical treatment, concealing illness, especially of this kind, and considering it a taboo subject. As a result, not only the body but also the soul ends up sick. Psychiatrists treat illness by making patients aware of unconscious mental blocks, then confronting and resolving them. Your narrator openly details her illness but doesn’t dare claim to smash any taboos, though this nevertheless can be considered self-help. The term ‘mourning’ actually suggests that while we can’t undo the past, we can focus on the future and hope for rebirth.

Or maybe, you there in the bookstore, you are a man. You may laugh and say: Breast cancer is something that only happens to women – what does it have to do with me? I’m sorry, but you’re mistaken. Breast cancer is like the sun, shining on women and shining on men as well. Moreover, by the time it’s detected in men, it tends to be more serious. No person is an island; you’re a man, but you may have a mother, sister, and possibly a wife or a lover – if your other half gets breast cancer, what will you do? While your attitude reveals your personal feelings and standards, I suspect that our fear and avoidance of cancer are due mainly to ignorance. Clinging to ignorance is also an incurable disease.

When all is said and done, this is a book written using a range of literary techniques. Some friends regard it as a novel, and others as a collection of essays. Dear reader, you’re welcome to categorise it however you’d like; this time, it’s up to you. It’s just that the life of the modern person is so hectic, and work is demanding. In your free time, take a walk in the country or by the sea, breathe the fresh air, swim, play ball games and look after your body. Perhaps it’s not worth spending too much time reading this book – you’re better off just flipping through a few chapters and choosing the ones that most interest you. If you’re curious about cancer, skimming seven or eight paragraphs of ‘The Doctor Says’ or ‘The Flying Guillotine’ is more than enough. Where appropriate, I’ve inserted prompts throughout the book so as not to waste your precious time. If you’re a self-preoccupied manly man, then scanning the section ‘Beards and Brows’ should suffice. If you’re a doctor, how about giving ‘Daifu Di’ a try? If you don’t like words and prefer looking at pictures, simply turn to the last few pages of the book – at first, there were only images, but I added some text, as I worried that staring solely at images might lead to a new kind of illiteracy. Are you someone who is hunched over a desk all day and enjoys sitting at home reading? ‘The Body’s Language’ was written just for you. We place too much emphasis on knowledge, at the expense of ignoring our bodies. Without a body, how would the soul have a place to rest? Are you about forty? Maybe ‘Maths Time’ is just what the doctor ordered – once you reach adulthood, you need to take responsibility for your own health. Is there a constant dull ache in your stomach? Have you packed on a few pounds? Are you chronically fatigued? Are you overworked? Please cherish your body and pay attention to your diet.

Maybe when you open this book, you’re sitting at home. Are you one of my real-life friends? You’ve turned to this book not because you’re in the mood for a story but because you’re wondering how I’ve been doing these past couple of years. Dear friend, I’m grateful for your concern. I’m actually quite blessed. The past two years of my life have been like a magic-realist novel, a blurring of dream and reality, as though I’m under a spell, my entire being an ethereal fiction, whereas the city, streets and friends within are all real. Yet am I not fortunate compared to someone who’s paralysed in bed, stuck in a vegetative state or afflicted with AIDS? I can still enjoy walking down the street and taking in the scenery, read some books, write a few words, and on good days, I can even take short trips. I don’t need to worry about putting food on the table, nor do I have to go to work. What more could I ask for? In these times, I’ve found I have far more friends than I realised, who treat me better than I ever could have imagined. I’m touched by the outpouring of care and support. Indeed, it’s because of friends that I’m reluctant to leave this world. I’m but a very cowardly person, no braver than anyone else. Thank you, friends, for rebuilding my confidence. I’ll live my life to the fullest.

— Xi Xi, June 1992

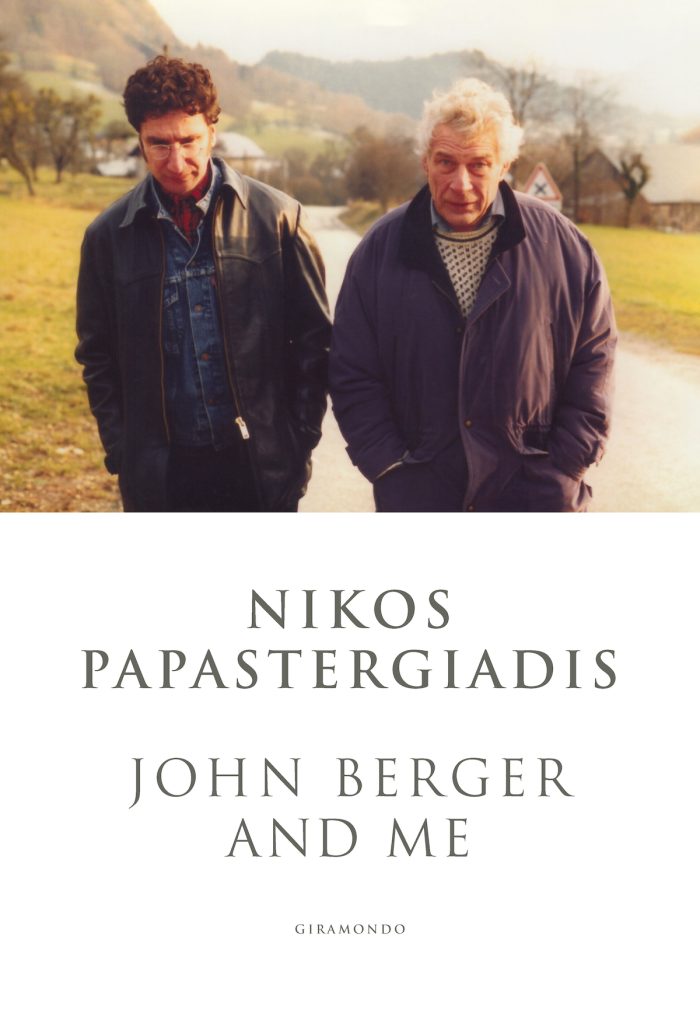

Nikos Papastergiadis: a note on John Berger and Me

Nikos Papastergiadis reflects on his new memoir, John Berger and Me, a memoir to the great English writer, poet and painter, and a tribute to an individual who was mentor, father figure and friend to the author.

John Berger was an artist, critic, novelist, playwright, essayist, film script writer, and actor. He was brilliant with words. He struggled passionately while he drew. When he was a presenter on television, he was utterly compelling and mesmerising. But it was uncomfortable watching him trying to inhabit other characters in films.

John lived in a peasant village in the French Alps.

His essays on art and politics and his stories on migrants and peasants hit me to the core of my being. Thirty years ago, I wrote my doctoral dissertation at Cambridge on the theme of exile in his writing. We met just as I was completing my conclusion.

A year later he rang: ‘Nikos, I had a little accident on my motorbike, and we might need some help to bring in the hay this summer. Can you come and stay?’

That was the beginning of an annual pilgrimage from Manchester to his village. When I arrived on my motorbike he would hug and dance with me like a big bear.

The kitchen was also a studio and an office. The outlines of portraits and drafts of novels were tested there. I witnessed earth shuddering phone calls with film producers and visits by artists and neighbours. The delight for hospitality in John’s eyes was a joy to behold. However, I also craved to steal him for myself.

In the morning, we would go to a local market. Later, we would help with the haymaking and do some repairs around the house. In the evenings we would cook and share stories. When he listened all the mountains were silent behind him.

After the cows were back in the barn I would look up at the stars and wonder if my father would have enjoyed such nights. This book reflects my time with John and seeks to explore the parallels with my own father, who was also called John.

John Berger left London after winning the Booker Prize. He went to find solidarity and comfort with the last generation of peasants in France. My father was a peasant and sought to find freedom and progress for his children. He became a factory worker in Melbourne. Through these two men I saw my life as a journey on a helix curve.

John Berger and Me began as a talk on friendship at the Greek Centre and unfolded into a reverie about the traces left by others. I feel as I have been talking to John all my adult life. He has been a touchstone to all my thoughts. It still aches whenever I go into a bookshop and realise that there is no new book by John.

— Nikos Papstergiadis, May 2024

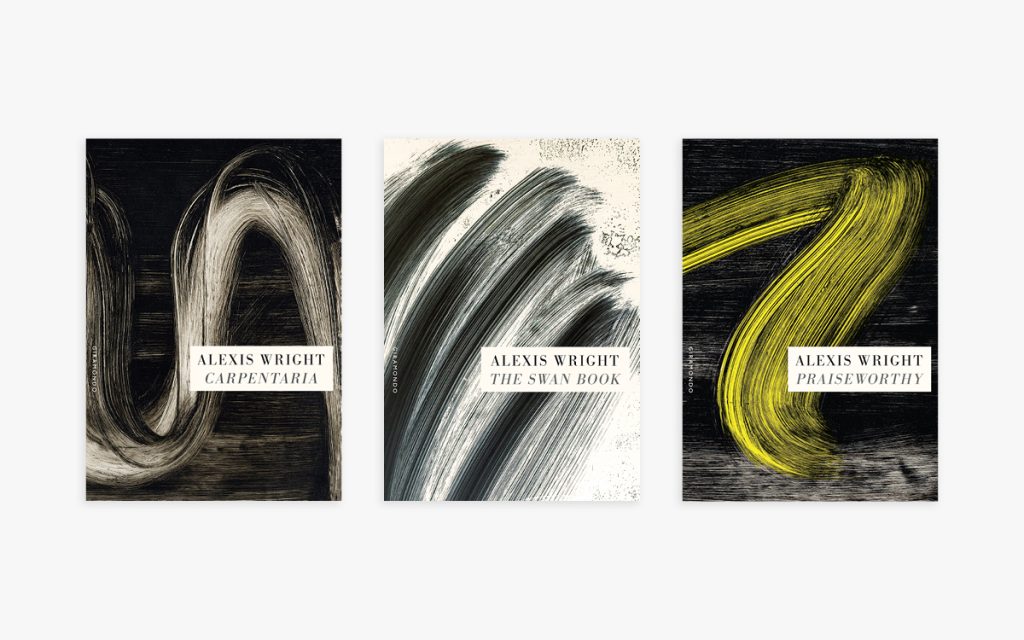

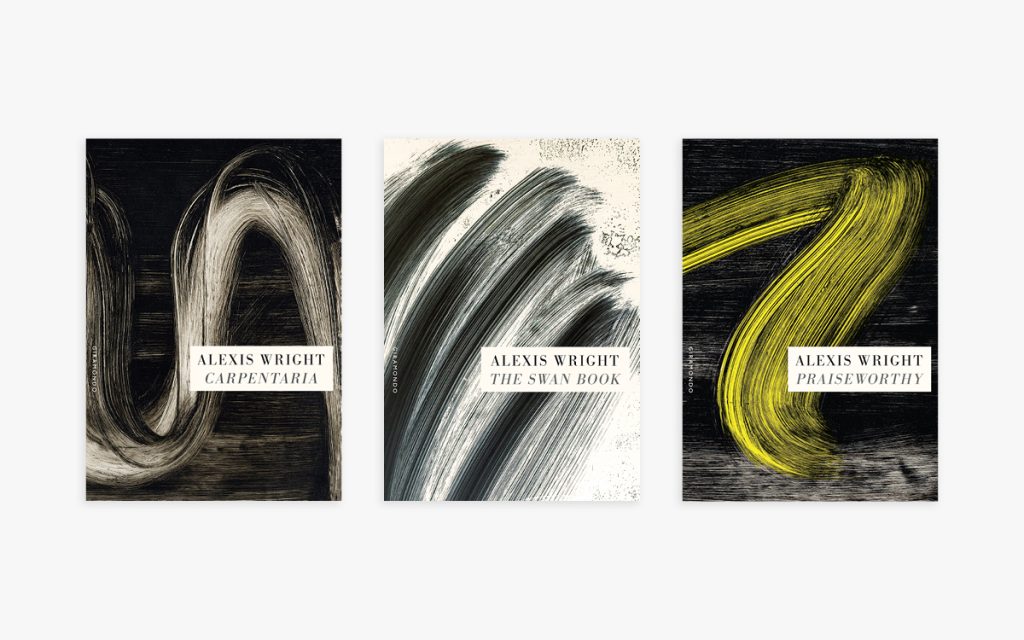

Alexis Wright wins ALS Gold Medal for the third time with Praiseworthy

Alexis Wright has won Australia’s oldest literary award, the ALS Gold Medal, with her epic novel, Praiseworthy.

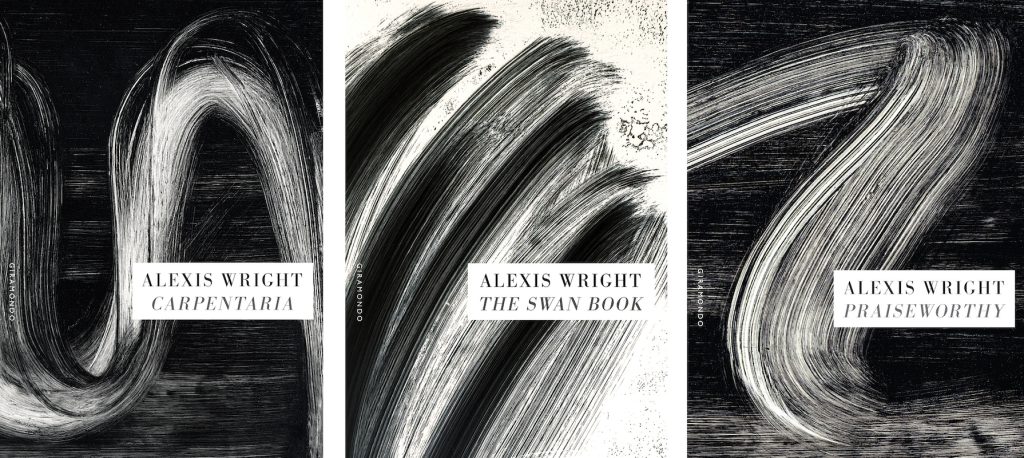

She joins Patrick White and David Malouf to be the only writers who have received this honour three times, having won it previously for her novels Carpentaria and The Swan Book. The medal is bestowed annually in recognition of an outstanding literary work in the preceding calendar year.

Since its publication in early 2023, Praiseworthy has won the Stella Prize, the James Tait Black Prize for Fiction, and the University of Queensland Fiction Book Award, and has been a finalist for many more Australian and international literary prizes, including the Dublin Literary Award.

Read the ALS Gold Medal judges’ citation below.

Alexis Wright’s astonishing novel Praiseworthy is a novel for and of our time; where time immemorial intersects with time running out. It is a political novel that deals directly with ‘The Intervention’ into First Nations communities from 2007 to 2012, which had been justified by government on the basis of widespread child abuse in First Nations communities in the Northern Territory. The novel turns an unflinching eye onto the irreparable damage done by these attacks on the psyche, body, soul and communities of First Nations peoples. The internalisation of degradation and disgust, which fractures both individual and community plays out with devastating effects in the Steel family and the town of Praiseworthy, as it battles the environmental catastrophe of climate change. In the wake of this broken, sacred covenant of people and place, both country and culture are fundamentally threatened, in extremis. The monumentality of the novel summons the scale of these betrayals and its voice recalls William Blake’s just prophet who ‘roars and shakes his fires in the burden’d air’ of a corrupted world. In the cosmology of the novel, the ancestors, the atmosphere, the land and the water are in open revolt.

Praiseworthy is hilarious, furious, poetical and painful, and all in large order. This depth and range does not effect a mediation or tempering of its rage. Praiseworthy refuses assimilation and insists that traditional custodians alone know how to inhabit in and with this place.

The monumentality of Praiseworthy is testament also to the duration of writerly attention and care, to an ethics of a sustained focus on painful injustice. The formal originality and scale of the novel stands as a response to the enormity of need but also to the depth of resources that survive.

Finally, Praiseworthy, like Wright’s other novels, teaches us how to read. When Carpentaria was first published in 2006, many elements were unfamiliar and required readers to question existing parameters of literary worlding and the relationship between form and meaning. The Swan Book also challenged us in these ways and more some. Reading Praiseworthy teaches us how to read Praiseworthy. We need to attend and listen to this literary elder about the need for literary creativity, ancient and new ways of literary sympathy, and the intimate connection of both to justice.

Alexis Wright and Sanya Rushdi shortlisted for Miles Franklin Literary Award

Alexis Wright’s Praiseworthy and Sanya Rushdi’s Hospital have been selected as finalists for the 2024 Miles Franklin Literary Award. There are six books on the shortlist, which was announced in on 2 July.

A few hours later, Praiseworthy was named the winner of the ALS Gold Medal, Australia’s oldest literary award. Wright now joins Patrick White and David Malouf in winning the ALS Gold Medal three times, having previously won it for Carpentaria and The Swan Book.

Wright and Rushdi were also both shortlisted for the 2024 Stella Prize, with Wright going on to win.

Judges’ comments, Praiseworthy:

Everything about Praiseworthy is expansive: its themes, its imagery, its vibrant demotic prose. The novel is at once an epic of classical proportions and a wild comedic romp. Set in a fictional town permanently enshrouded in a mysterious haze, the story takes a quirky Indigenous family and renders them in mythical terms. The patriarch, a crackpot entrepreneur and visionary called (among other things) Cause Man Steel, hatches a harebrained scheme to preempt impending environmental collapse by cornering the donkey market. The ructions this generates within the small community of Praiseworthy and his exasperated family develops into a monumental, swirling and often brilliantly funny narrative that grapples with the largest issues of our time: climate change, the internet, capitalism, the devastating consequences on Indigenous communities of colonialism and ongoing political paternalism. A stylistic tour de force, its tone capable of switching in an instant between the lyrical and the wickedly satirical, Praiseworthy triumphantly assesses its themes against the ultimate measures: the timelessness of Country and the indomitable spirit of Aboriginal Sovereignty.

Judges’ comments, Hospital:

Hospital is a fictional flourish of poetic utterance that is, in turns, affecting and absorbing in its disquisition upon the nature of psychosis. Based on the experiences of the Melbourne-based Bengali writer, the work is an illustration of what the narrator identifies as “someone’s picture turning out superbly, accurately representing a social system.” psychosis takes us through the corridors of treatment regimes of psychotic illness, while evoking the philosophical and political underpinnings of what constitutes the individual and the social. As the narrator navigates her way through these communities, she brings to us a world peopled with every rung of society. The short narrative is autofiction and testimonial, delineating the gap between normative family structures and friendships that are formed in medical establishments. The chronicle makes us wonder about the slippage between reality and fantasy, thought and language, humour and pain, defeat and joy. Ultimately, it is a feat of imagination undertaken by an utterly original voice rooted in contemporary Australia’s multicultural, multilingual ethos. Originally written in the author’s mother tongue, the book was translated by Arunava Sinha and retains the sparse economy and piercing psychotic insights of the source text.

The 2024 Miles Franklin judging panel comprises Richard Neville, Mitchell Librarian of the State Library of NSW and Chair; literary scholar, A/Prof Jumana Bayeh; literary scholar and translator, Dr Mridula Nath Chakraborty; book critic, Dr James Ley; and author and literary scholar, Prof Hsu-Ming Teo.

The 2024 winner will be announced on 1 August 2024.

Further reading

‘First timers and indie publishers dominate Miles Franklin shortlist’ Sydney Morning Herald

‘Book experts on the surprises and likely winner of Australia’s biggest literary award’ ABC Arts

Judith Beveridge: a note on Tintinnabulum

The renowned Australian poet Judith Beveridge reflects on her much-anticipated new collection of poems Tintinnabulum (1 July 2024), the first since her prize-winning Sun Music in 2018. Read an extract from the book here.

Tintinnabulum explores what poetry can uncover through musicality and analogy, how these elements can open up sacred spaces. I have chosen Tintinnabulum as the title (which means the ringing of little bells) to suggest celebration and to indicate that many poems in the collection engage in an almost ritualised observance of precise aspects of the physical world. I look specifically at animals, landscapes, and at people in certain environments.

Sacred spaces, I believe, come into being when we perceive relationships and apprehend interconnections. I have always been interested in the ways in which similes and metaphors can create relations that formerly might have been unnoticed. My poetry has centred around this core aspect of poetic language and Tintinnabulum continues this with perhaps more urgency and power, but also with humour and surprise.

I also love to use language that is distinctly focussed on sound as a way of enhancing meaning and providing pleasure for the reader. My animal poems, which make up the book’s first section, delve into how we often interact with cruelty and insensitivity to non-human animals, but I also look at ways in which encounters with animals throw their ‘otherness’ into stark relief such as the distinctly alien lives of cicadas, leeches, bluebottles.

The second section focusses on the human world and brings to bear a sense of compassion for the difficulties that people encounter: surfers on a high sea, a waitress unhappy in her job, two brothers suffering racist cruelty, as well as elegiac poems about friends and family members.

The third section consists of imaginative/hallucinogenic scenarios, and is my most poetry at its most weirdly inventive. This section culminates in a joyous romp through sonic repetitions and is a homage to the poetry of Wallace Stevens.

The poet Edward Hirsch has said that ‘Attentiveness is the natural prayer of the soul.’ I believe the final section of the book attempts this level of worshipful attention evoking the beauty and awe to be found in landscapes. It is my aim that readers, after reading Tintinnabulum, will find the world less fragmented and more interconnected, that language can be felt as an activating mechanism for wonder, joy and revelation.

— Judith Beveridge, May 2024

‘Two Houses’: a poem from Judith Beveridge’s Tintinnabulum

Two Houses

for Stephen

I found a rental with tall trees just beyond the back fence.

It was peaceful except for the three a.m. Friday freight

train slowly pulling the weight of its wagons along the tracks,

wheels grinding, couplings shrieking, derailing our sleep

for at least that six minutes of a much longer run

to get the goods into Sydney. Wherever it had come

from—Brisbane, Casino—that train would have travelled

through the night, a two-kilometre chain rattling

sleepers awake, but we didn’t mind so much because

often at that hour, we’d hear the powerful owls

close by in the trees and we’d get up, take the torch

and wait for the light to show in their eyes, red beacons

flashing on and off like lighthouses if they blinked.

They were so close we could see the mottling and barring

of their feathers, layers of white and grey highlighted

with brown and charcoal chevrons, strong claws

gripping a branch. We’d listen for the slow, deep soundings

of the male, then the higher pitched call of the female,

a short catechism resolving territory and distance.

We watched at dusk, too, for their flight—soundless

distillations of moonlight in the shadows and the trees.

There were flocks of cockatoos also, like that freight

train shrieking us awake, taking us out into the timbered

dawn, our new haunt of astonishment. Everything

that year was new: your move from interstate, my shunting

an unsalvageable marriage to its dead-end siding, the gambit

we took in changing our lives. I’ve heard powerful owls

are the only birds that can carry more than their own

weight. No wonder they became our talismans. Once

we saw a mother owl feeding three juveniles, tearing shreds

from a dead possum. We’d find possums in the reserve

neatly eviscerated, the kills always silent… We live

elsewhere now, our own place. Sometimes, still, we hear

an owl, a male’s wooing, and territory-declaring to bring

a mate in close. But we’ve only seen an owl once,

when sitting out in our yard, it alighted on a low branch,

its pearl-ash and dusty-grey feathers made it look like a puff

of fog against the apricot blush of dusk. Watching the owl

again I thought of how far we’d come—all the actions,

workings, means, and mechanisms across time and distance

to pull to its destinations this rich consignment of love.

From Tintinnabulum by Judith Beveridge (2024).

Author note: Hasib Hourani on rock flight

Hasib Hourani reflects on his debut book rock flight (1 September 2024), an epic poem and a moving testament to the displacement and dispossession of the Palestinian people.

rock flight was originally just one poem. It was short, maybe two pages. I had a bad day and wanted to write it down but unknowingly had exposed something cursed and irreversible that demanded transcription. Two pages sprawled to become a chapter, that chapter gained another. And so on.

A book-length poem split into five chapters, rock flight is about many things: settler violence, hyper-surveillance, birds, boycotts and my family. Parts of it are quite literally haunted. Entire sections couldn’t have been written if I hadn’t gone somewhere else to write them down. I took my computer interstate to start and finish a chapter that remained unread and untouched for a year afterwards. The final edits were done from a high stool at the laundromat. There are words we can’t bring home with us.

It’s perhaps for this reason that the book often uses inference to get the words across. Fixating on a recurring set of images—rocks, birds, water, flight—explicit language is hinted at, omitted or redacted. A gesture towards censorship and a consideration for my own safety, of course, but also a reclamation of language. The book is cheeky and combative. I want the reader to smirk. I want them to scrunch up a piece of paper and throw it across the room.

I made a lot of rock flight’s final changes in September and October 2023. We couldn’t have known then that the zionist entity would double down and massacre over 40,000 Palestinians in Gaza between the book’s completion and its release. It took four years to write this book. But the words themselves didn’t change much from one draft to the next, they simply moved around: from one line to the next, from the afterword to the body. Mimicking the relentless motion of Palestinian experience.

All of this to say, the words and stories in rock flight aren’t new. References and accounts date as far back as 1799. I wrote a contemporary poem that contains centuries of history, and fossilised within that graft is something eternal.

Translator note: Jennifer Feeley on Xi Xi’s Mourning a Breast

An excerpt from translator Jennifer Feeley’s afterword in Xi Xi’s Mourning a Breast (July 2024). The book is the first English language translation of Xi’s groundbreaking work of autofiction, first published in China in 1992.

Xi Xi (西西, also known as Sai Sai) was one of the most beloved and celebrated authors in the Sinosphere. Though she published nearly forty books in her lifetime, spanning a wide range of genres, until recently she has been largely under-served in translation. Officially named Cheung Yin, she began publishing under the pen name Xi Xi in 1960, inspired not by the name’s sound or meaning but by the visual appearance of the Chinese characters: the character 西 evokes the image of a girl in a skirt with her legs akimbo in a hopscotch square, and the character’s doubling suggests the movement of skipping from one square to another, just as frames in a film create an illusion of motion. This rationale for Xi Xi’s pen name is characteristic of the joy and whimsy that her writing exudes.

…

In 1989, Xi Xi was diagnosed with breast cancer, and she began to write Mourning a Breast intermittently during her treatment and recovery. Published in 1992 in Taiwan, the book was received as the first literary work to chronicle a Sinophone woman writer’s journey with breast cancer. It was a success with both critics and readers: the China Times in Taiwan named it one of the best ten books of 1992, and it won United Daily’s Readers Best Book of the Year Award. It was loosely adapted as a film in 2006 (2 Become 1, directed by Law Wing Cheong), and a simplified Chinese edition was published in mainland China in 2010 by Guangxi Normal University Press.

Although Xi Xi’s cancer never returned, the damage she had sustained in her right hand from one of the treatment procedures led to a gradual loss of mobility; by 2000, her right hand was fully non-functional, and she trained herself to write and work with her left hand. As a form of physical therapy, Xi Xi began to sew and soon developed an interest in handicrafts, building dollhouses and making cloth dolls and stuffed animals. She exhibited many of these works publicly, and under the name of Ellen Cheung she was named the Designer’s Collection Champion at the second Hong Kong Teddy Bear Awards. She also transformed these hobbies into books, such as The Teddy Bear Chronicles, a playful photographic showcase of handmade teddy bears modelled after figures from Chinese history and Western culture, and The Monkey Chronicles, a unique cultural history of monkeys, featuring photos of hand-sewn puppets with accompanying text, designed to heighten public awareness about conservation.

…

One of the first Chinese-language works about breast cancer, Mourning a Breast was considered groundbreaking for its time, delving into both the physical and psychological responses to the disease, exposing common myths about breast cancer and confronting the shame often associated with it. Likewise, Xi Xi’s exploration of the gendered aspects of the disease, especially what it means to lose a part of the body so traditionally tied to one’s gender and sexual identity, could also be viewed as radical. And yet, certain elements of the book may seem dated to the contemporary reader. In this regard, it is important to view the text as a cultural product of the early 1990s, specifically pre-handover, colonial Hong Kong, acknowledging that there have been huge advances in medicine and science and changing understandings of sex and gender. Though one of Xi Xi’s aims in writing this book was to encourage people to look after their health, one should not turn to this book for specific medical advice. Still, more than three decades after its initial publication, Mourning a Breast continues to be a source of encouragement and companionship to readers, with insights about illness and body literacy that remain not only relevant but profound.

…

Of course, the guiding light behind my translation has been Xi Xi herself. I had very much hoped that she would have seen this book come to fruition with her own eyes. I am honoured that she trusted me with her words, allowing me to transport her extremely personal story into English. Even more than that, however, I cherish her friendship, and I am heartened that her gentleness and warmth live on through her writing. Xi Xi was unfailingly compassionate, generous, observant, unassuming and funny, and her love for her city, especially its young people, never wavered. When I returned to Hong Kong in July 2023 for the first time since the Covid-19 pandemic, I visited Xi Xi’s final resting place at the Diamond Hill Garden of Remembrance, joined by friends and writers Ho Fuk-yan, Stuart Lau, Louise Law Lok-Man, Lawrence Pun and Eva Wong Yi. As we paid our respects to the modest memorial plaque displaying her legal name and black-and-white photo, we agreed that she needed some miniature toys to accompany her. Afterward, we ate lunch at a dim sum restaurant overlooking Victoria Harbour in the Cultural Centre that Mourning a Breast describes as resembling a bathroom.

As Xi Xi contemplates in the preface, ‘The term “mourning” actually suggests that while we can’t undo the past, we can focus on the future and hope for rebirth.’ This book is not only about mourning a breast, but also mourning an ever-changing Hong Kong.

Author note: Kate Fagan on Song in the Grass

Prize-winning singer, songwriter and poet Kate Fagan reflects on her new book Song in the Grass (1 June 2024), a sonically rich collection in which poetry becomes a way of sustaining love over distance, a collective music, and a compass for navigating in-common emergencies.

Song in the Grass feels to me like a record collection. It’s a handful of favourite albums, a box of lyrics, a soundtrack to living in the Blue Mountains while walking over ‘the long bridge of motherhood’, as the book might say. But it’s also an almanac of environmental care, and a love letter to poetry as an art that is most alive when shared in communities. With other players and listeners – just like music.

The shoots of this book germinated when I met Irish writer Dermot Healy. His ear was attuned precisely to the music of natural worlds, and to people’s ways of finding language in the sky and stones, or among the reeds in lakes. I couldn’t put down Healy’s A Fool’s Errand, a long meditation upon what can be illuminated by the enduring migrations of barnacle geese. It reveres birds – not as ciphers or metaphors for human experience – but as sentinels of non-human worlds, whose navigations happen in spaces and scales far beyond our ‘selves’. Talking with Healy was like hearing an ego dissolve in water, such was his profound ability to honour voices and lives other than his own, by singing in place and time.

Living in the Blue Mountains on Dharug and Gundungurra Country, I am moved daily by ecological movements and displacements. Every bird carries a musical signal about the weather, about available food, about noisy developments and clearings, about other creatures. That plain reality holds immense power for me. Land and climate justice involve many kinds of reckoning. We are surrounded by art and stories that show us how to act upon these urgent calls, if we choose to listen.

I’ve been lucky in recent years to work with a splendid group of musicians and performers for whom I’ve written lyrics as kernels for compositions, collected in Song in the Grass as ‘Notes to a Bird’. I’d love readers also to hear the music those poems inspired, and by which they are shaped. Collaboration is a jacket I always want to wear; making work in company produces stronger art, which I’ve tried to acknowledge in ‘Letters to Writers’. It releases you from your own preoccupations and habits, and revitalises language and purpose.

I’ve been asked often about my fascination with lists and archives. There is something undeniably tender about encountering the traces of people’s everyday lives in collections of salvaged detail. Good living is an antidote to bad history. Bodies are kinds of archives, full of astonishing traces of humour in response to absurdity, or love as resistance to brutality. Lists never pretend that everything can be known or accomplished; they are always unfinished, provisional. They are always referring to other things. It’s part of my creative method to store up material evidence that flocks in peripheries, with intense curiosity for what it might affirm about imagination and joy.

In reflecting upon Song in the Grass, I can’t help making new lists. The book indexes slow time, emergencies, rituals, hope, sonics, death, translation. If one poem expresses what resonates across the whole collection, it might be ‘Border House (Notes to a Bird)’ – here’s a remix:

— Kate Fagan, 6 May 2024

‘Immigrants’: a poem from Kate Fagan’s Song in the Grass

to Bob Fagan

If my Grandad had seen the future

he would have said, small acts of care

are worth leaving. He’d have painted

imitation grain on window casing

and planted Crystal Palace lobelia.

My bride stunned us in faux fur,

he’d have said—I didn’t expect her

to outlive me by sixteen years.

He’d float like spume on Jervis Bay

and under casuarinas at Sanctuary

Point and say, now I know paradise.

He’d make tea for Mum and Dad

before breakfast, Tang at lunch

and shepherd’s pie on a Monday.

He’d enlist to fight fascism and stand

straight backed. He’d cross the Suez

on the Castel Felice, watch comedy,

say he wanted a daughter like me.

He’d bounce on his heels and organise

mints at the phone table. He’d hear

pneumonia coming and live until

Cathy Freeman won gold. He’d walk

on the shores of Lake Burley Griffin

and say, not everyone will love

this town. He’d shoe horses

at Sezincote, flood an orange orchard,

lug for the MSO, cry in a dorm

at Fisherman’s Bend. He’d be stoically

sentimental, gravely proud of his son.

He’d kiss my children and clutch

their shoulders, too modest to say

my brother’s boy resembled him.

He’d tinker in sheds, hum over

weekend newspapers, buy bacon

at Vincentia butcher so Nanna

could fry us holiday sandwiches.

If my Grandad had seen the future

he would have said, at Monte Cassino

some things were lost forever. He might

take back that year but no others.

‘Immigrants’, a poem by Kate Fagan from Song in the Grass (2024).

Praiseworthy by Alexis Wright wins James Tait Black Prize for Fiction

Praiseworthy by Alexis Wright has won the prestigious James Tait Black Prize for Fiction, worth £10,000 (A$18,958). One of the United Kingdom’s longest running literary awards (founded in 1919), the prize is presented annually by The University of Edinburgh’s School of Literatures, Languages & Cultures.

Previous winners of the prize include DH Lawrence, E.M. Forster, Graham Greene, Muriel Spark, Christine Brooke-Rose, Margaret Drabble, Nadine Gordimer, John Berger, JM Coetzee, AS Byatt and Zadie Smith.

The fiction panel found Praiseworthy to be ‘a brilliant and experimental work of fiction that stretches the boundaries of the novel form in new and exciting ways. Engaged with matters of climate and justice, Praiseworthy’s innovativeness is matched only by its timeliness.’

Fiction judge Benjamin Bateman, a senior lecturer in English Literature the University of Edinburgh, called Praiseworthy ‘a kaleidoscopic and brilliantly conceived novel that interweaves matters of climate and Indigenous justice in prose that accomplishes the most difficult of feats – being funny and simultaneously ferociously engaged with some of the most pressing ethical and political questions of our contemporary moment’.

In her response to the award, Alexis Wright commented: ‘I am really pleased that the judges on the fiction panel have acknowledged the innovative nature of Praiseworthy, and appreciated the scope of my intentions with this work. I intended Praiseworthy to be a a big book in more ways than one. I hope its scale and scope is right for the times we live in.’

The book was chosen from a shortlist of four titles, with an academic judge working with a panel of researchers to critically assess the shortlisted works and decide on the winner. The prizes are also the only major British book awards judged by literature scholars and students.

Said Bateman: ‘Alexis Wright’s Praiseworthy stood out to our student readers for pushing the novel form in new directions and for depicting, with impeccable nuance and humour, the moral complexity of trying to make a life under conditions of governmental dispossession and slow violence.’

The announcement comes a fortnight after Praiseworthy won the 2024 Stella Prize, and in the same week it was longlisted for the 2024 Miles Franklin Literary Award and the 2024 ALS Gold Medal.

The book was published in the United Kingdom last year by And Other Stories, and in the United States this year by New Directions. In Australia, it is available in both paperback and hardcover. It was described by the New York Times as ‘the most ambitious and accomplished Australian novel of this century.’

Grace Yee wins Ockhams NZ Book Award for poetry with Chinese Fish

Grace Yee has won the 2024 Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry for her verse novel and debut book, Chinese Fish. The prize is administered by the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, which were this year announced in May at a ceremony in Auckland.

Yee holds dual citizenship in Australia and New Zealand, with Chinese Fish distributed on both sides of the pond. Earlier this year, the book also won the 2024 Victorian Prize for Literature, Australia’s most generous writing prize worth $100,000.

‘I am thrilled that Chinese Fish has been acknowledged here, in the country where I grew up,’ wrote Yee in her acceptance speech. ‘It is, at its heart, a story about a family that travelled across the seas, arrived in Aotearoa, and had the audacity to call it home.’ The speech was delivered by Paula Morris on Yee’s behalf.

Read the judges’ comments on Chinese Fish below.

Grace Yee’s is a striking aesthetic – it blurs genres, it dances around the page, it crosses languages by fusing Cantonese-Taishanese and English, both official and unofficial. Her craft is remarkable. She moves between old newspaper cuttings, advertisements, letters, recipes, cultural theory, and dialogue. Creating a new archival poetics for the Chinese trans-Tasman diaspora, the sequence narrates a Hong Kong family’s assimilation into New Zealand life from the 1960s to the 1980s, interrogating ideas of citizenship and national identity. It displaces the reader, evoking the unsettledness of migration. In Chinese Fish, Yee cooks up a rich variety of poetic material into a book that is special and strange; this is poetry at its urgent and thrilling best.

Find a roundtable interview featuring all of the Ockhams Poetry finalists published earlier in the week here.

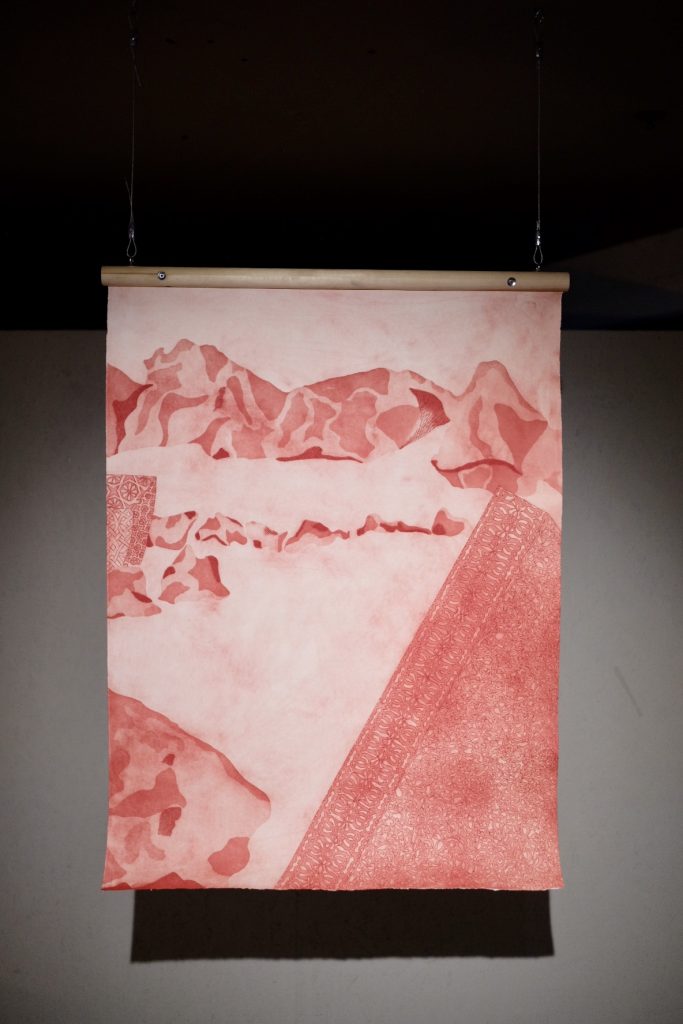

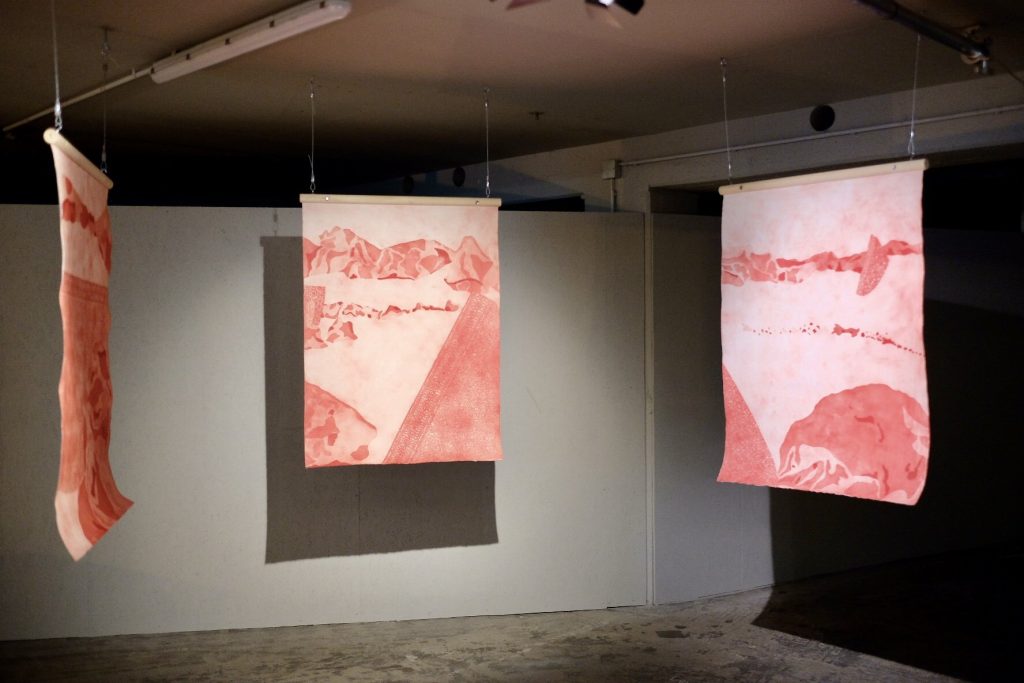

Artist note: Shireen Taweel on the cover of The Tribe (2024) by Michael Mohammed Ahmad

Shireen Taweel reflects on her artwork Astro Architecture. A detail of this work – made from engraved copper plate and aquatint prints – was used as the basis for the cover image of the new edition of The Tribe by Michael Mohammed Ahmad.

Astro Architecture sits within a future landscape. A speculative landscape of migration into Space, a movement of peoples and spiritualities working to decentre the colonial past, present and future of Space travel. Astro Architecture proposes architectural affirmations of the sacred for future Space migration and pilgrimage. A vision of sacred architecture to contain spiritual knowledge systems, and places for community gatherings of ritual and ceremony to build relationships of sustainability between the non-living and living landscapes of a future in Space.

Astro Architecture is informed by the astronomical and celestial navigation instruments and technologies of the Arab sciences and the impact on the movement of people for migration and pilgrimage, as well as the significance of the architectural representation of the sacred for this movement. The print series reflects upon existing celestial navigation instruments of the Arab Sciences as a source of shared cultural histories, memory, identity, colonised and decolonised collections of movement, which contributes to the potential decolonising of Space activity and visions of a multicultural, progressive, and equitable future in Space.

The application of the heritage engraving techniques used to embellish astronomical instruments, and the recording and mapping of astronomical knowledge has been employed by the artist to hand engrave the large copper plates for the prints. The three sacred architectural forms reference the astrolabe, quadrant and sextant, astronomical devices used to measure the distance between two objects and of immense spiritual virtue. The pierced patterns on the forms are inspired by the intricate embellishment of the astrolabe, an ancient astronomical instrument used in Islamic and European cultures as both a scientific and spiritual navigational tool and the most advanced pre-telescope technology.

— Shireen Taweel

78 x 106cm. Image courtesy of the artist Shireen Taweel and STATION Australia. Photo: Ian Zainab Salem.

Artist bio

Shireen Taweel’s practice reflects the diasporic landscape she inhabits as a Lebanese Australian, employing cross-cultural discourse around the construction of cultural heritage, knowledge, identity, and language. Through sensorially immersive installations that draw on architecture, Islamic science and ritual, Taweel brings to light histories and cultural practices that have been buried beneath the weight of social political power structures. Her most recent work rests speculative astral architecture upon a diverse foundation of past celestial technologies.

The development and research for her projects are often site-specific, working in collaboration with local communities, their architecture and their environment with a focus on experimentation in material and sound through site. Through the contemporary use of heritage coppersmith artisan techniques, including engraving and hand-piercing, Taweel’s works create a space for shared histories and fluid community identities.

Alexis Wright wins the Stella Prize for the second time with Praiseworthy

Alexis Wright has won the Stella Prize for her epic work Praiseworthy, described by the judges as ‘a canon-crushing Australian novel for the ages’.

At the announcement ceremony on Thursday evening, Beejay Silcox, chair of Stella judges, said: ‘Praiseworthy is not only a great Australian novel – perhaps the great Australian novel – it is also a great Waanyi novel. And it is written in the wild hope that, one day, all Australian readers might understand just what that means.’

In winning the Stella for Praiseworthy, Alexis Wright has become the first author to win the award twice, having previously received it in 2018 for Tracker, her collective memoir of Aboriginal leader Tracker Tilmouth.

Praiseworthy has also won the Queensland Literary Award for Fiction, and is currently shortlisted for the Dublin Literary Award and the James Tait Black Prize for Fiction. It is published internationally in the United Kingdom and North America. Read interviews with Wright in ABC Arts, the Guardian, the Sydney Morning Herald, and many more media outlets.

Read the judges’ comments on Praiseworthy below.

Fierce and gloriously funny, Praiseworthy is a genre-defiant epic of climate catastrophe proportions. Part manifesto, part indictment, Alexis Wright’s real-life frustration at the indignities of the Anthropocene stalk the pages of this, her fourth novel.

That frustration is embodied by a methane-like haze over the once-tidy town of Praiseworthy. The haze catalyses the quest of protagonist Cause Man Steel. His search for a platinum donkey, muse for a donkey-transport business, is part of a farcical get-rich-quick scheme to capitalise on the new era of heat. Cause seeks deliverance for himself and his people to the blue-sky country of economic freedom.

Praiseworthy walks the same Country as companion novel, Carpentaria, published in 2006, and here, Wright demonstrates further mastery of form. Reflecting the landscape of the Queensland Gulf Country where the tale unfolds, Wright’s voice is operatic in intensity. Wright’s use of language and imagery is poetic and expansive, creating an immersive blak multiverse. Readers will be buoyed by Praiseworthy’s aesthetic and technical quality; and winded by the tempestuous pace of Wright’s political satire.

Praiseworthy belies its elegy-like form to stand firm in the author’s Waanyi worldview and remind us that this is not the end times for that or any Country. Instead it asks, which way my people? Which way humanity?

— Judges’ report, 2024 Stella Prize

Interviews with Alexis Wright following her Stella Prize win:

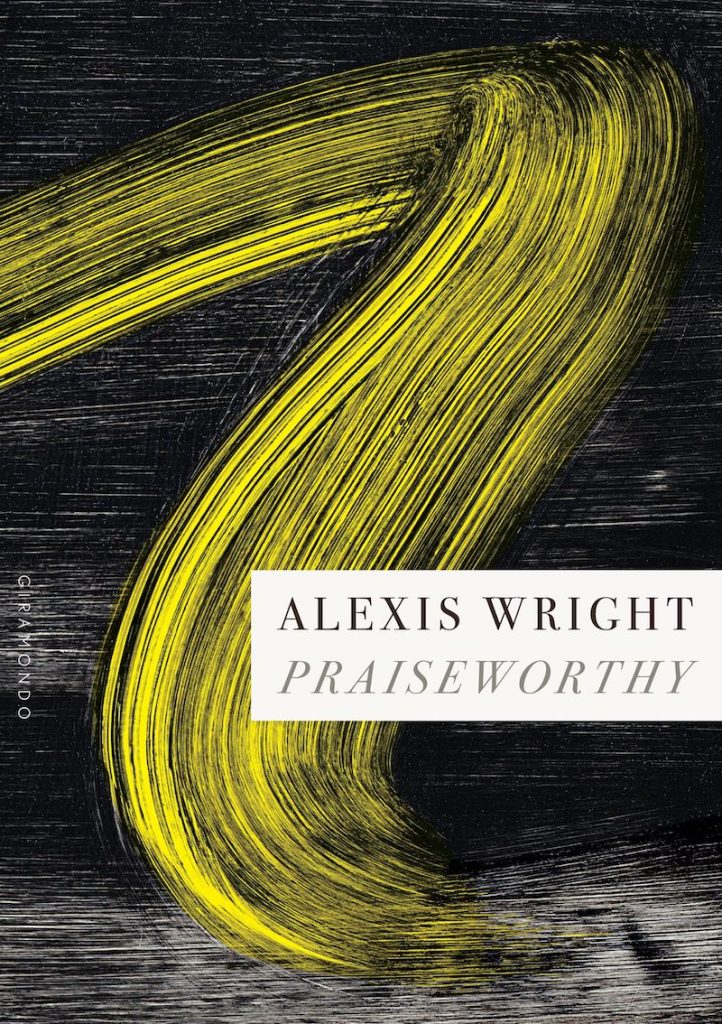

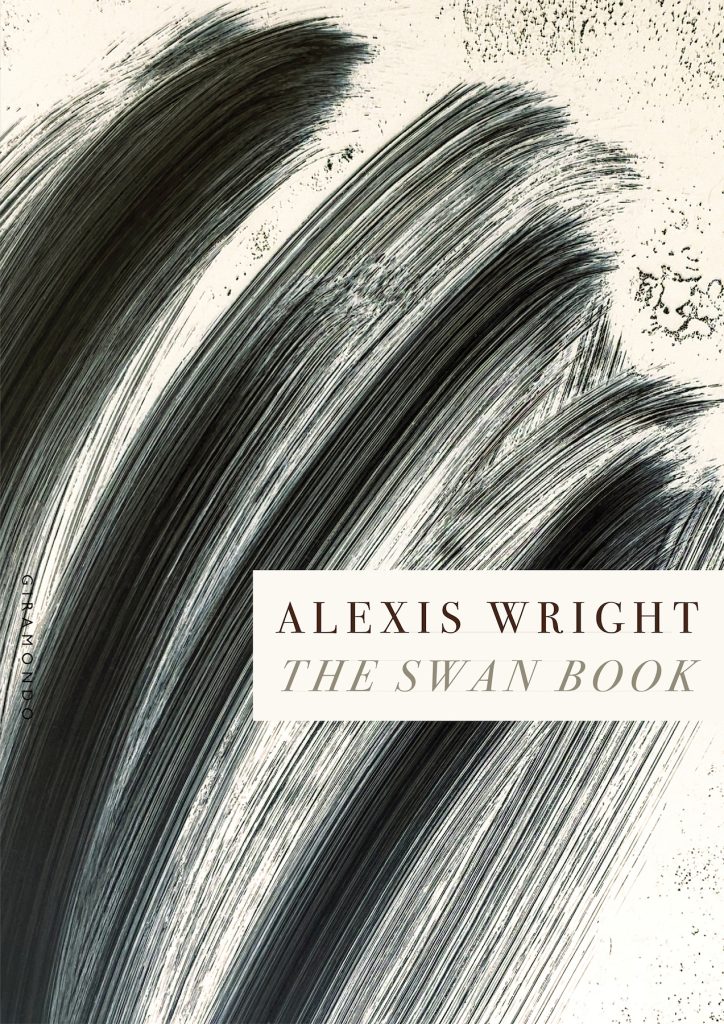

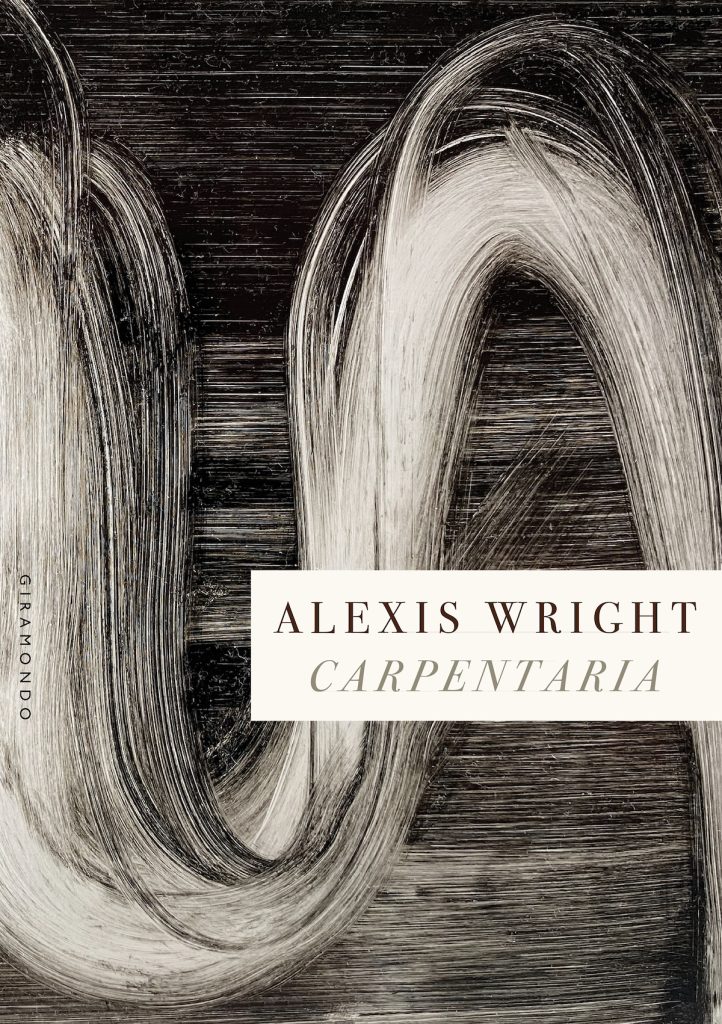

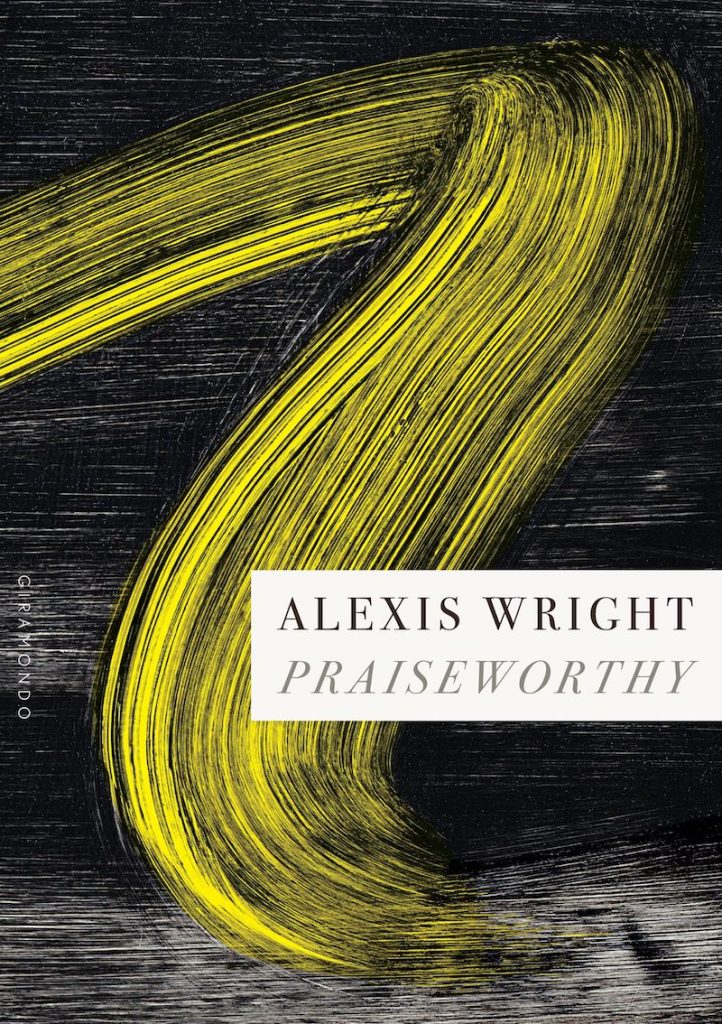

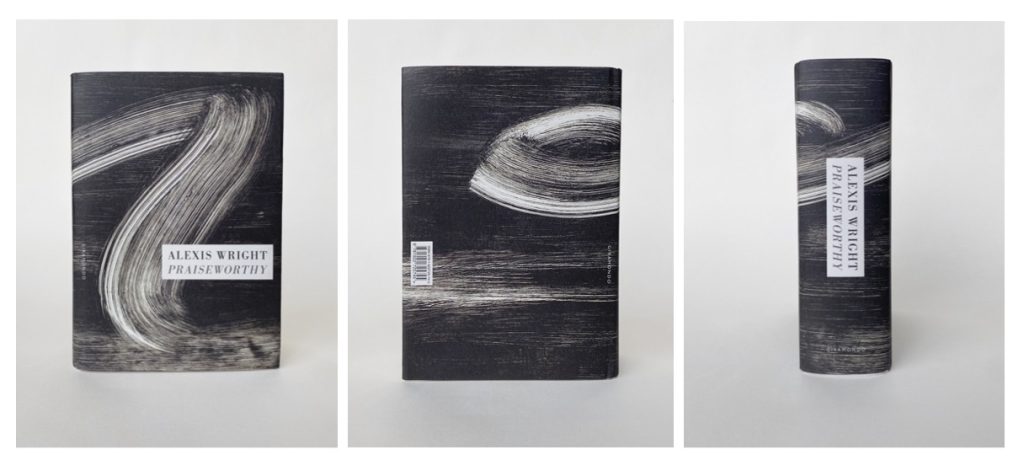

Jenny Grigg on designing the cover for Alexis Wright’s Praiseworthy

Jenny Grigg discusses her process in designing the hardcover edition of Alexis Wright’s latest award-winning novel, Praiseworthy. The design was shortlisted for the Australian Book Design Awards.

As the Praiseworthy manuscript was being resolved, I was wondering what handmade techniques I could use to convey the authenticity and qualities of Alexis’s writing. After lots of tests and discussions, while away on holiday and limited to the materials available in a suburban Spotlight, a series of smears made by pushing ink across the smooth surface of acetate showed potential. The tarriness of the printing ink helped me to inhabit the power in Alexis’s writing. I had to use strong hand movements to force the ink across the surface. My right hand cramped. Conceived as more than a front cover, while the ink smears were drying, I bent the prints to imagine how they would appear wrapped around the book’s volume; a process that helped the perception of the jacket as a landscape that wrapped a book.

‘All these butterflies floated and spun into a silent screeching of hot air in this atmospheric flooding…’

I was working on a suite of cover designs for three of Alexis’s novels at the time, and, typical of working abstractly, the ink smear selected for Praiseworthy originated as a rendering of a swan intended for the cover of The Swan Book. As Giramondo Publisher Ivor Indyk’s brief highlighted, many passages in Praiseworthy featured butterflies as if they were ‘force fields’, and an interpretation of this appeared when I flipped and rotated the swan image. The form dynamised the concept. A storm picks up on the front cover, pushes around the spine, and appears to tail out on the back cover. I like the monochrome. With no distractions from colour, the sense of space and texture created by the process suggests a mythological atmosphere. The addition of yellow on the cover of the paperback edition modifies the meaning of the original image a second time. The storm becomes butterflies, ‘floated and spun’.

Autumn Royal’s launch speech for Naag Mountain by Manisha Anjali

Naag Mountain by Manisha Anjali was launched in April 2024 at The Alderman in Brunswick East during a sold-out evening event. The event featured a speech by poet Autumn Royal in honour of releasing Manisha’s debut book into the world. The speech was followed by a haunting and transcendental vocal and harp performance by Genevieve Fry. Read a transcript of Royal’s speech below.

The following speech was delivered on the unceded lands of the Wurundjeri Woi-Wurrung people of the Kulin Nation. We acknowledge and respect their Elders, both past and present. We extend this respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals who may read this speech. Always was, always will be Aboriginal land. We also wish to express that from the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.

I first physically met Manisha in a garden. It was 2019 and we were reading alongside each other at a house fundraiser for the Djab Wurrung Heritage Protection Embassy. But I do not doubt our spirits already knew each other intimately as years earlier, Manisha’s stunning poetry gushed into my psyche, and I was enraptured and now – I am here.

At this point, it feels necessary to summon (or depend upon) the words of the brilliant Eunice Andrada when she expresses that Manisha’s ‘Naag Mountain is an exquisite work that resounds with the reminder of what can be reclaimed when a community moves towards their awakening: their dreams, their futures. This is a distinguished debut collection from a poet whose vision is urgent and consuming.’

‘Urgent and consuming’. I respectfully echo Andrada’s words as I attempt to form an articulation of Manisha’s Naag Mountain and the significance of its existence. Speaking about this book in front of you, dear audience, is a privilege and beyond this scripted reading, I promise to consider how I can ever return such a deep honour.

As Manisha explains in her author note to accompany this work of brilliance: ‘Naag Mountain is the recovery and aftermath of the girmit, the period between 1879 and 1916 when Indians [derogatorily termed ‘coolies’] were taken to Fiji for indentured labour on Australian-owned sugar cane plantations’. Manisha’s Naag Mountain potently and generously illuminates the realities of the cultural and cellular inheritance of this indentured labour through a collaboration of dreams, oceans, archival documents, songs, ancestral historiographies, and poetry.

Naag Mountain also reveals a complex and intertwined circuitous narrative spanning across times, oceans, and realms. Within Naag Mountain, there exists an imaginary film called ‘Paradise‘. As Manisha eloquently describes this film within the text:

In this film, the actors are allowed to walk away – to reject their scripted roles and embrace their continuous evolution of identities between human and non-human beings. The existence of the film, ‘Paradise’, allows for such action. The poetry surrounding this film, ‘Paradise’, also generates an action, but without containment. As Naag Mountain declares, nothing should ever be contained.

‘Paradise’ correspondingly brings awareness to the concept of ‘depiction’, and the deplorable truth that this film, this narrative of ‘Paradise’, should already be known and that these actors should have always had agency and dignity.

I quote another passage from Naag Mountain where such agency and dignity are allowed, encouraged, and guided by spirits across oceans in a moment where the actors:

Naag Mountain is an epic poem in which the concept of the ‘single and distinctive hero’ is not just overturned by Manisha’s captivating poetic voice and defiantly vivid expressions, but completely quashed. This is not done out of spite or in a cruel manner – but through a multitude of polyvocal voices, bodies, entities, spirits, animals, elements, and sensations that challenge the notion that there can only be one dominant account of history. As Manisha’s expressive voice guides me over the phone: ‘The Indo-Fijian psyche does not just inhabit the physical realm’.

Radical metamorphic bodily changes occur throughout Naag Mountain during violent scenes and traumatic events, but most significantly, these transformations also take place throughout moments of deep love and celebration. There is also the metamorphosis of yourself as a reader – something that is so very crucial and so very sacred. As Nancy Gray Diaz elucidates, metamorphosis ‘represents the conjunction of self and world, and it plays out the individual’s conflict with, or assumption into, the values of that world’.

Interconnected with metamorphosis is a meaningful and poignant theme in this book is the birth and rebirth as ‘Paper jackal fly out of my mouth, and / into the misty air, and into the monsoon’ (p. 8).

With such lines, both birth and rebirth are intricately woven and profoundly expanded upon throughout the entirety of Naag Mountain with keen attention and generous dedication.

In this work, in Naag Mountain, all matters expressed are actualities and are not merely metaphorical representations. Here, in Naag Mountain, ‘metaphor’ as a concept is considered too simplistic and detached for such a profound understanding of what is occurring. In Manisha’s own words: ‘through the process / of extraction, I see my responsibility. It is standing still at / the top of the mountain (p. 31). There is a view from the top of the mountain and Manisha is showing it to you, dear reader.

At this point in my scripted act, I have exceeded over 300 words. Three – the number ‘3’ – and the time of 3 a.m. is extremely poignant and forceful in the actuality of this work and the history it is based upon. This is the time when ‘the coolies’ were ordered to rise from their dreams and begin work. It is also known as ‘the suicide hour’, a bodily sacrifice often performed as an act of resistance against ‘the company’ that once ‘owned’ Manisha’s family. The Colonial Sugar Refining Company.

I will end/open with Manisha’s evocative and powerful description of ‘this company’: