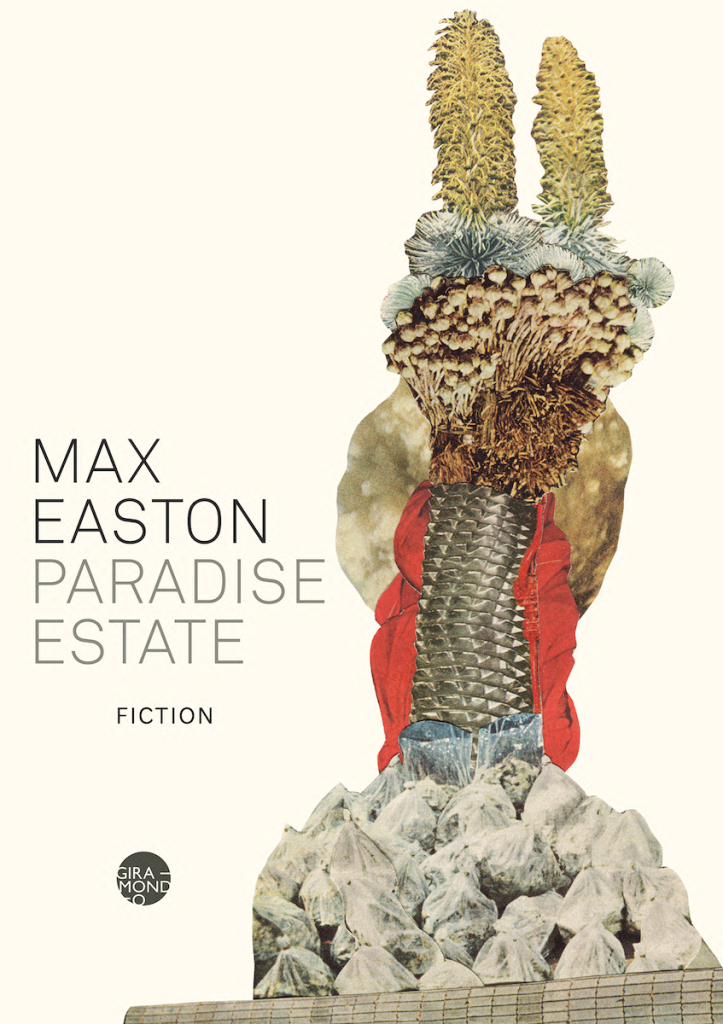

Three vignettes from Paradise Estate by Max Easton

On a muggy, bright and rain-spattered day in November at the low-slung Pratten Park Bowling Club in Ashfield, Max Easton launched his second novel. Almost two years had passed since the launch of Easton’s first, The Magpie Wing, which also celebrated its entry into the world at the bowlo, and which went on to become a finalist for the Miles Franklin. In the nearby suburb of Hurlstone Park, and perhaps known only to Max himself, was the real-life house that the author walked by a few years ago and began him thinking about the book which would become Paradise Estate.

The launch featured live music from local bands Mope City and Zipper, as well as Max reading of six ‘vignettes’ from the pages of Paradise Estate. Three of these vignettes have been published below.

From p.71

Dale bought another round for the old fellas at the Crystal Palace Hotel. He’d been roped into their conversation about former State of Origin greats, and while he usually liked to drink alone, he appreciated this excuse to keep drinking. After some hectoring, Dale told them about the circumstances that lead to him being made redundant (‘who doesn’t wank at work?’ the eldest at the table said, and when the youngest was hesitant to support Dale, the older man yelled: ‘what are you a priest?!’). Dale laughed meekly with these people, who he felt a comfort with, a generation who had never picked him up on his behaviour. To most that he knew, he didn’t seem to come across as ‘likeable’, and it showed. He’d react pre-emptively to the distaste he saw people feel towards him. It made him sensitive and jumpy, and when stretching that energy over a day, he became tired, and gaunt. And that made him look unwell. If he told friends about this anxiety, they’d try to reassure him by saying, ‘it’s all in your head’ but he would reply: ‘I know! That’s the problem!’ Then his friends would run out of patience and advise him to seek ‘professional’ help, which yielded the same advice delivered over several hour-long sessions—only it came with a bill attached, and sometimes a prescription. He was constantly humming with this energy, his eyes darting, his breath short and laboured, trying to take his ex-girlfriend’s advice, that: ‘no one could possibly hate you as much as you hate yourself.’ That had never helped either.

From p.81

‘Nathan, I’m sorry to bring this news to you, but we’ve received another complaint about one of your essays. It’s an anonymous one again, so we’re not sure how to take it. It’s…another plagiarism accusation. If you can call me back when you get a chance…that’d be great. Thanks.’ Nathan knew this one wouldn’t stick. This ‘anonymous’ member of the community going to each of the editorial committees he volunteered his time to, picking apart every word he said and claiming it was someone else’s work. He was no more a plagiarist than anyone else! Sometimes he’d receive a good pitch by a new contributor, reject it, and write it up as his own, but no one could pin that on him as far as he could tell. This complaint suggested that his recent article (criticising the She-Hulk production team for deflecting criticism of the show’s low-quality CGI by claiming it was ‘body shaming’ the titular character) had an identical argument to an essay published years prior (a defence of the Joker movie’s location shoot at a stairwell in Harlem that since became a tourist destination, stating that any critique of a unionised location shoot gave fuel to the push towards all-CGI sets). In the end, the editorial board had to throw out the complaint; Nathan had published the She-Hulk essay under his own name, and the Joker article under a pseudonym.

From p.162

‘What’s wrong?’ Sunny asked a pale-faced Helen, who entered their shed with a bucket of KFC at midday. ‘I went into the church,’ she said, looking overawed, ‘there were nuns.’ When Sunny started howling in laughter, Helen snapped, saying that ‘it’s too fucking cold’ and she needed some reprieve from the winter. Too fried after her all-nighter on Beth’s acid to get any further than the corner of the street, her blankets damp to the touch, shivering through the house, hoping there might be some kind of warm snack inside the church to tide her over until the KFC opened. ‘One of the nuns talked to me,’ she said conspiratorially, starting work on her bucket, ‘she knew about our house. She told me to take a seat. It was really weird.’ Sunny took a piece of chicken and tried to find a deeper psychological reason for Helen’s decision to walk into a church for the first time in her life, but Helen grew impatient, took her chicken away from them and said that no, she wasn’t in need of help from a higher power, because she was ‘beyond redemption anyway.’