On ‘Claiming the Colossus’ by Evelyn Juers

I have been re-reading Helen Garner’s fiction for work, and there’s a story of hers, ‘What We Say’, which begins with two friends at the Sydney Opera House, watching a morning dress rehearsal of Rigoletto. Afterwards, the women visit another friend’s house, tear-stained and flushed, where they gobble up pasta and chat about how one of men’s greatest fears – losing their daughters to a world of sex – drives so much of literature and art. Then the conversation turns to what might be women’s fundamental fear, and what might be the principal theme of women’s art:

‘We don’t have a tradition in the way you blokes do,’ I said.

Everybody moved with laughter and relief.

‘There must be a line of women’s writing,’ said Natalie, ‘running from beginning till now.’

‘It’s a shadow tradition,’ I said. ‘It’s there, but nobody knows what it is.’

Evelyn Juers’s essay ‘Claiming the Colossus’ unearths a line of women’s writing and writing about women, a shadow tradition. It’s not the only tradition nor is it a linear, unbroken line. But it’s there, stretching across centuries, hostile to the diminutive, the obliging, the practical. This is an essay about the gigantic – women who seem permanently pitched skyward, whose articulations overpower, and have the capacity to rupture and then obliterate. It’s about the enormity and hot terror of self-expression, where words do not formulate slowly in mouths but instead ‘leap from lips’. This isn’t the stuff of sensible ambition – it’s loftiness and extravagance and total grandeur! The colossus, Juers writes, is ‘a site around or over or in the light of which one wishes to move, to be seen to move. It is a fixture and a fixation, a grand projection’.

Her colossi are manifold; Juers finds them in the work of Elizabeth Smart and Sylvia Plath, Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, and in Anna Blunden’s Pre-Raphaelite painting of paused labour, The Seamstress. Ideas of inheritance, domination, divinity, and the power exchanged between fathers and daughters loom over the essay with both humour and menace, like gargoyles on top of churches. Juers’s attention is not only on the glory of the colossus but on its eventual ruins; she picks through the remnants and holds up the shards to the light.

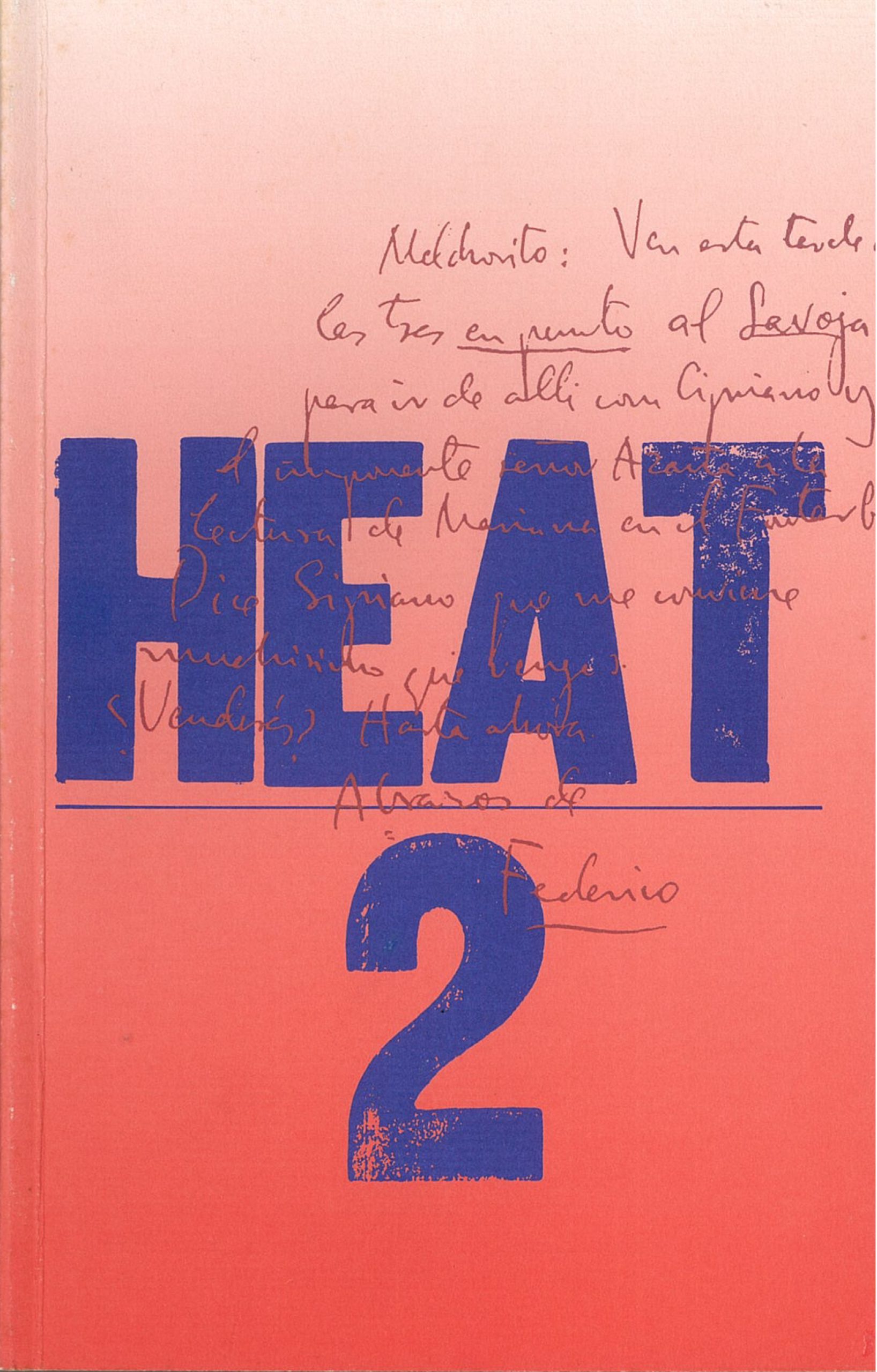

I found Juers’s essay in an old copy of HEAT that I picked up at a Salvation Army store. I nearly missed it – it was dwarfed by a giant tome of D.H. Lawrence’s Collected Works on the shelf. At the time, I had been finishing an essay on diaries and self-expression, that mentioned a few of the same writers – Helen Garner, Hélène Cixous, Anaïs Nin. Juers’s writing left me gleeful and dizzy. I also felt retroactively deprived, feeling as if I had come to something too late, or after I really needed it. But then I was reminded of another shadow tradition: women writers who make leaps across time to tie together loose knots and formulate new lineages, throwing the forgone and the definitive off balance.