In CameraArrested Motion and Future Mourning

In the fourteenth century, the Great Plague swept through Europe. In Florence, between a third and a half of the entire population perished. Between 1349 and 1351, Giovanni Boccaccio wrote his masterwork, The Decameron. He did not write it to provide a happy alternative to the plague. He wrote it, he said, to cure melancholy, particularly to cure women of lovesickness, though this did not save him from accusations of misogyny. But it seems he also wrote it to provide a glimpse of a world outside the confines of the house, when the home was under siege. It was supposed to be an indoor fantasy of a place elsewhere. This ‘elsewhere’ is the product of a melancholy which runs beneath and beyond Boccaccio’s provision of a so-called ‘happy ending’. Boccaccio’s work is prose which had not yet given birth to the novel. Cut off from the epic and the sublime, its yearning is for stability and permanence, but here is found the first signs of the unconvincingness of its social ‘lesson’. It would take a Cervantes or a Rabelais to provide antidotes to melancholy in the form of humour, exaggeration, and in the suspension of moral judgement, upending the cautionary tale in order to damn all moralising. In Boccaccio’s world though, melancholy is represented as a contradiction, part ‘lesson’ and part catastrophe, turning a cure into a condition.

Boccaccio’s methods, unlike Dante’s (from whom he borrowed extensively), are terrestrial and tyrannical: power is invested not in God but in the narration of Man. Boccaccio’s approach to storytelling is therefore realistic and splenetic, offsetting the divine and the fateful. It is indicative of a fork in the road, between what the French call writers of the stomach, Hugo and Zola come to mind, and writers of the spleen, like Baudelaire and Proust. Writers of the stomach are social thinkers, realists and positivists, while writers of the spleen can only imagine failure, can only evoke depression and anxiety, driven into a self which is at times infantile, at times perplexed; both revolutionary and conformist in that it can never quite instigate insurrection. Of course a writer can be in both of these categories, as Boccaccio’s work seems to show. But in order to examine this early bifurcation which manifested as a contradiction, it may be worthwhile to take a look at Italian Renaissance humanism and to see how melancholy made its way back into contention as a creative humour during the devastation of the Great Plague.

Antiquity had set sadness in stone. Its melancholy did not carry the ambivalence of the modern sensibility…it was, in a sense, bicameral; schizoid, directed by voices; contradictory rather than ambiguous.1 The act of writing, it seems to me, is about brooding and dissatisfaction, but it also embodies the paradox of being robust, since it has to represent, in no small part at least if it is to be literature, the Real. It also has to sustain reception, an implied reader who is also a critic. To write, therefore, is to act, to perform and to sustain. A self-address rather than an expression of self. It therefore owes a lot to the ancient idea of sadness which had to be acted out; in effect, a mourning for loss. Unlike Montaigne’s melancholy, which reconciled the essayist with living amidst appearances, Boccaccio’s is a performance, very much consumed with a social reality. This robustness seems so out of date with our modern classification of individual pathologies that it leads me to think that because writing is for the most part so mired in the past, since of course, imaginative memory is always of the past, that the ancient word melancholy should be reserved solely for the condition of writing, not for the condition of the writer. Not a writer’s disease, because obviously many non-writers have it, but a ‘writing disease’ because creative writing cannot say what melancholy is, and this constriction forces a different kind of production, an inability to mourn. To write sadness is not the same as creating writing that is sad. To say: ‘I am melancholic’ in a piece of writing does not convey the experience of melancholy. While melancholy cannot be expressed, it is nevertheless couched as an absence within writing. It can only be signified and represented, in descriptions of landscape, for instance. In writing therefore, I contract the other through representation, which is the loss of myself. The ‘I’ as Rimbaud said, is an Other. So by writing, I am impoverished. I am part of its loss, but I cannot say what that is. The ‘writing disease’ therefore, is productive through impoverishment and constriction, because it has lost the certainty previously provided by the voices of the gods. It produces through diminishment; it writes against social norms which would like to make it healthy and normal; it gives value to the distinction of melancholy as both suffering and productive. The Decameron, it seems to me, indicates the moment of change between antiquity and the modern sensibility.

Overtly, Boccaccio tries to present a remedy for lovesickness, but love is hardly the subject of his stories. Despair, suicide, deception and disaster take centrestage. Like Robert Burton after him, remedies for melancholy are very much subsumed by his interest in the subject itself. The subject of The Decameron is melancholy. And there is very little consolation. The apodeictic or moralising conclusions in the stories are repeatedly left to cynical or ironic interpretation through a lack of conviction; a quick turnaround without effect. What lingers, however, is a foreboding, a gloom, a sense of disaster. The plague, both real and metaphorical, is always outside.

In his book Melancholy and Society, Wolf Lepenies suggests that there is a direct link between the aristocratic court jester, Baudelaire’s dandy, Benjamin’s flâneur and the solitary, reflective, eccentric modern melancholic. Reading this progression backwards can also be helpful in understanding The Decameron. The court jester, as Lepenies notes, ‘was employed to dispel melancholy – or, to put it in modern terms, was an “entertainer”…His function was to stablilise the system’s “interior”, namely the court.’2 But his other purpose, I suggest, was to license exhilaration arising from possible catastrophe. The court jester was seldom censored for prophesying doom, but to avoid execution, he had to be very skilful at allegory. I would like to suggest that in The Decameron, the inaction resulting from stabilising the interior is combined with apocalypse and fantasy. While making overtures to stability by invoking society’s norms, Boccaccio’s darker purpose was to drill a hole in the dam wall holding back disaster. Sadness in his protagonists is madness. While the French word tristesse signifies an intelligent or sensitive sadness, the Italian tristezza implies a more robust malignity or madness.

I am particularly interested in such contradictions, which may be inherent in the idea of associating melancholy with creativity. In The Decameron, we find an early example of melancholy as artistically productive, not only in the coercion of each storyteller to produce stories (all of which are of course written by Boccaccio), but in the stories’ inventiveness in trying to keep melancholy at bay. There is an essential sociability, a weave, a connection between the tale-tellers which, when set against the plague outside, expresses an emerging Florentine sensibility, not only of siege and fatality but of an increasing civility, pageantry and connection with the public world. A pageant is a play, but it is also a performance intended to deceive. There is a certain amount of jesting and jousting. There is order in disorder. This is inherent in the framework of The Decameron. The word Decameron comes from two Greek words meaning ‘ten’ and ‘day’. To seek refuge from the plague, ten narrators spend ten days in a country house, each telling a story a day. A queen or a king is nominated each morning, responsible for a song at the end of the day. This practice of story-telling was recommended by physicians of the time. It was said to preserve the balance of humours and to chase away melancholy and restore mental health. I couldn’t think of anything worse than such a writing residency, but it must have forced Boccaccio into anxious creativity, trying to present an allegory, and I would suggest, not quite succeeding against the verdict of reality, in this new form called a novelle, which we would today categorise as a collection of short stories.

In the Middle Ages, as melancholy scholars have pointed out, a thinker imbued with the contemplative life didn’t meditate to master himself, but to get closer to God. The Renaissance introduced the ‘speculative life’, which produced a new man, responsible only for himself and for his mind. This celebration of the intellect in competition with itself became more powerful than the respect for sanctimonious contemplation. With this power of the individual came the pitfalls of pride and the recognition of man’s natural limits. Oscillating between hubris and despair, society and the individual, the modern, anxious genius was born. A melancholic new man, bipolar, splenetic and carrying the taint of both tragedy and genius, had been created by Italian humanism. He was the homo literatus or literate man, who first made his appearance not as superhero but as writer and reader; not as healer but as solitary melancholic. Boccacio’s protagonist Nastagio is just such a character, at a fork in the road.

It is fifth day and the eighth story. The queen for the day is Fiammetta, and she sets the theme, where lovers pass through disasters before having their love end in good fortune. There must be a happy ending to all Day Five stories. The storyteller is Filomena. Boccaccio is still trying to escape charges of misogyny by having two women involved in the construction of this tale. But I think this is only the surface of the argument. There is much irony in the idea of a happy ending. There is in fact an absence of happiness. During the writing of The Decameron, Boccaccio fell in love with a woman. He interrupted his work to write La Fiammetta, the name he gives to his lover. The critic John Addington Symonds wrote:

It is the first attempt in any literature to portray subjective emotion exterior to the writer; since the days of Virgil and Ovid, nothing had been essayed in this region of mental analysis. The author of this extraordinary work proved himself a profound anatomist of feeling by the subtlety with which he dissected a woman’s heart.

Boccaccio himself wrote in his prologue that ‘one piece of good fortune…remained to me out of so many that had been lost – namely, the power of knowing that seldom if ever has a smooth and happy ending been granted to love.’3 So why is he prescribing a happy ending in this story if he already knew this? I suspect he was writing against himself, thinking he could ‘cure’ melancholy. But he was, in effect, trapped by his subject.

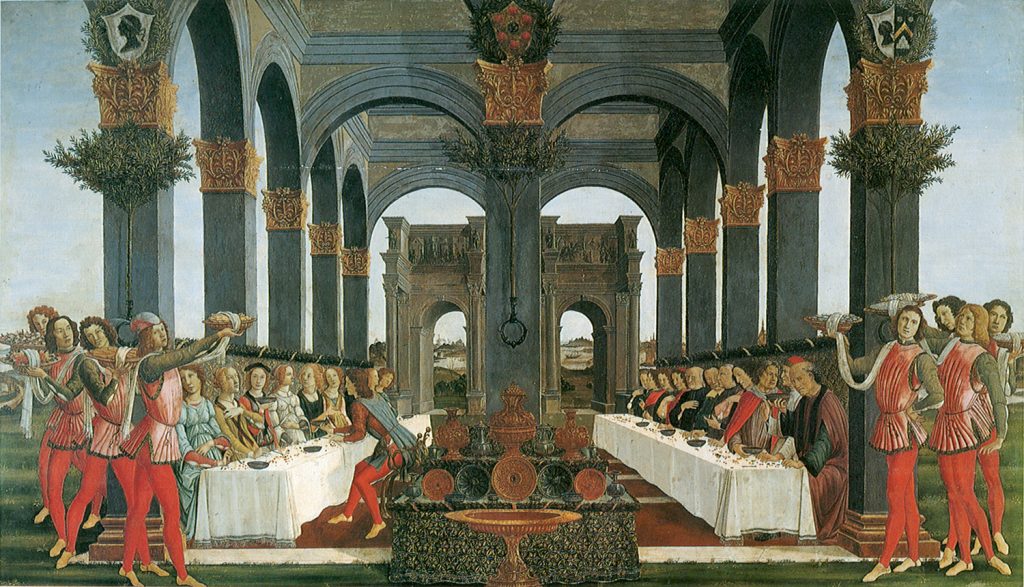

Let us turn to the story. (In 1483, Sandro Botticelli painted four panels entitled the Story of Nastagio degli Onesti. Most likely, these were commissioned by a wealthy family for the marriage of a son. These are his representations of the scenes.)

Wealthy Nastagio is in love with a lady of noble lineage from the Traversari family, but she despises him. He squanders his money on her, but she doesn’t respond. Discouraged, Nastagio contemplates suicide, leaves Ravenna and in the wilderness, in the forest of Chiassi, witnesses the frightening scene of a young woman being chased down by hounds and stabbed by a knight.

The knight explains to Nastagio that he and the young woman are both dead souls in torment, doomed to repeat the scene. The repetition is part of the punishment for his having committed suicide in despair at being rejected by the lady. The lady in turn is punished for her pride and cruelty in rejecting the love of the knight.

Nastagio has the idea of making arrangements to have his beloved witness the scene. He arranges a banquet, inviting his family, the Traversari family and all his friends. At the precise moment in the afternoon, the knight appears, with his hounds tearing at the maiden before him. He performs the ritual stabbing.

When the Traversari girl, who is present at the banquet, witnesses this scene, she changes her mind about Nastagio and agrees to become his wife.

This tale is amongst the most violent and cruel of all the stories in The Decameron. The physicality of suffering is set in the context of an abstraction, a dream-like setting. Whatever moral advice that is given at the end sounds false and unjust. While purporting to dedicate his book to the curing of melancholy in women, Boccaccio actually advocates the repression of desire. The Decameron therefore, is not a health book of the time designed to cure melancholy through entertainment, but an early form of shock treatment. What is staged, in the ancient Greek sense of trauma and catharsis, in the Freudian severing of the psychoanalytic moment, is the restoration of the Law; pushing back the disorder of anomie while permitting the melancholic moment; the moment of loss which traverses two worlds; the dominion of the dream and the kingdom of the law. Boccaccio, following Dante, tries to invest his narratives with these two realms. Heaven and hell, the outside and the inside, the known world and the world beyond the horizon. But there is a strange liminal quality about this story. There is no God; no divinity. It incorporates trauma in order to exert an obligation to think of happiness ever after. But the contractual foundation of the story is precisely the reader’s acceptance of apocalypse. It reminds me of what Julia Kristeva wrote in her book Powers of Horror, when she says:

On close inspection, all literature is probably a version of the apocalypse that seems to me rooted, no matter what its socio-historical conditions might be, on the fragile border…where identities…do not exist or only barely so – double, fuzzy, heterogeneous, animal, metamorphosed, altered, abject.4

It is this kind of liminality that Nastagio’s story embodies. He takes a Dantesque journey from pestilential city to garden paradise, but it is all in his mind. The outside fantasy is conducted inside the room, in fact, one could say in camera, a testament to Boccaccio’s virtuosity. The lack of transparency between inside and outside, the confinement and the yearning, the inability to take action by going outside, by taking the plunge into the street, is an aesthetic stance. It is about practising one’s melancholy in secret. Social mores are underscored by trauma; courtly love is given over to unspeakable horror. The eternal return of the knight and the maiden in their horrific performance is not so much a borrowing from Dante as a reversal of the Inferno. It is a static reversal of any salvation through sanctity. The saintliness of the Traversari girl in refusing the hand of a Machiavelli is turned on its head. Sin is rewarded and saintliness disgarded out of fear. The emotional conclusion is not about Nastagio and the girl living happily ever after, but dismay and despair at her having been menaced into marriage. All these aspects can be ascribed to a kind of arrested motion, a fear of disorder which inscribes a catatonia. In fact, the knight’s story is a form of hypnosis, mesmerising all who try to intervene, causing instant alarm and subsequent paralysis.

—

In his book Social Theory and Social Structure, R. K. Merton outlined a typology of the individual’s relation to society.5 He distinguished five modes of adaptation: conformity, innovation, ritualism, retreatism and rebellion. Melancholy is overloaded with a resignation that never reaches rebellion. Resignation stems from a surplus of order. The individual then retreats into melancholy. According to melancholy scholar Wolf Lepenies:

Retreatism is subject to social condemnation, because it calls society into question without attacking it; its deviance is based on pure passivity. According to Merton, ‘deviants’ – who are condemned in actual life – find compensation in the realm of the imagination. Yet they always remain isolated. Their passivity does not allow them to lead a life as part of a group, but rather grants them a private, individual existence.6

Living in society but not belonging to it, melancholics subscribe to a loss of order but are arrested from enacting rebellion because they uphold the same culturally prescribed goals as the society. Innovation and creativity may be a response to this inaction. I am reminded of the Indigenous, diasporic or migrant writer in Australia. While there is little evidence amongst them of a subscription to a unified national identity, there is also a disinclination to be sequestered from the benefits of mainstream society. While the idea of a national literature prescribes a dominant ideology, writing against the grain produces experimental and revolutionary energy. It also provides critique. While there can be no ownership by the melancholic of the structures of power, there is a complexity of representation available to the writer which demands attention and calls for testaments not to authenticity, but to virtuosity. There can be no backward motion without signifying victimisation, and no forward motion into a new ideal world. But there is a need to be witnessed, more than usually, for the employment of rigour and the exigencies of art. This marginal play is where melancholic writing takes place.

The conclusion I draw from Boccaccio is therefore that of an opening out to a fork in the road: the melancholic’s dilemma is always the need for stability and the need for flight: both stomach and spleen. It is arrested motion. On one arm of the fork, the repetition of the knight’s tale dramatises a certain taedium vitae or ennui. Freud’s idea of repetition-compulsion is that the need for a calm and settled life – here represented by the ideal of marriage – is fraught with a need to return to catastrophe, incurring suffering and pain. On the other arm of the fork, Nastagio himself can be read as being nostalgically unhoused, camping there in the forest of Chiassi outside Florence, trying to be solitary but failing; fantasising but unable to flee. Flight therefore, is always at the vanishing point of perspective, yearned for, but unattainable, Baudelaire’s Invitation au voyage, an interior voyage. Observe the vanishing point for which the ships are making in Botticelli’s painting of the first banquet.

Nastagio is an emblem of this melancholic ideal, a representation of the creative writer, inviting his audiences to a banquet of neuroses, or as Georges Bataille said, to the ‘fearful apprehension of an ultimate impossible’.7

One of the primary creative moments, the moment at which a writer begins, because of the necessity to be witnessed, the moment at which he or she takes on a voice, a form, as Susan Sontag calls it, is a moment of flight to and from a familiar pain. It is a revisiting of trauma through pageantry, a promulgation of the death of oneself. The wrong path is always beckoning.

Nastagio’s per-version, or his wrong turning, his dis-order, is his introspection in revisiting the knight’s scenario. His despair, his repetition-compulsion to seek the wrong path cannot release his yearning for a place elsewhere. His pavilion in the pine forest of Chiassi is an agoraphobic space. He attempts to control this fear of emptiness by inviting friends and putting on pageants.

I am interested in this fear of immensity and the need to fence it in; a melancholic fear of the nature outside and the need to domesticate it. It is a preoccupation of early colonisers in Australia. As Paul Carter says, agoraphobia involves a movement inhibition.8 But this concept of inhibition is also a bridge to the larger continent of historical space. In other words, understanding an historical topography as a psychic constriction precludes the desire to dominate and to control it. One is haunted by ownership. Indigenous songlines are a good example of how bad things happen if one transgresses a given space.

In the end, Boccaccio constricts his tale with a moral caveat about spurning one’s suitor. The unconvincing and over-determined ending demonstrates a binary: between the stability of the law and the flight of lawlessness. Boccaccio is caught in the camera eye in the performance of a contradiction. He is transparently a Renaissance Man in the spotlight, without the guiding light of God. His solution is to end the story. This is precisely the condition of melancholia in the context of creativity – how to break free without a guiding light. How to transgress without denouncing oneself as having taken the easy path. The anxiety of originality leads back to the melancholy of the unhappy present. To set this in an historical context, it wasn’t until the fifteenth century that the Florentine intellectual elite came to this fork in the road: no longer affirming scholastic justification for melancholy as part of a God-given world order, they moved the argument in favour of personal experience. They saw a fundamental ambivalence in Saturn, that of weakness and creative power; a merging of pathos with poetics. But Boccaccio hadn’t quite reached this point. There was no God, but neither was there rebellion.

Here is Botticelli’s fourth panel. Notice that order has been restored. The columns are symmetrical, the wedding party is orderly, the woman has accepted to be Nastagio’s wife. Her fate is sealed. But it is not a happy ending. There is no eros driving the lovers mad. In fact, it is hard to spot the unhappy couple. They seem to be missing. The object, once attained, is no longer wanted.

There is an absence of happiness, and Boccaccio was aware of this in his truncation of the ending. More to the point though, is the fact that the social order subjugates individual subjectivity – a particular irony in our postmodern times where there are unfounded claims that subjectivity is spoken through social discourse. Boccaccio domesticates this to a melancholy that is the real issue of a forced marriage. Throughout this whole tale, there has been no illustration of the power of the individual will. The woman, who is not named, represents the unspoken, unable-to-be-expressed moment of loss. Boccaccio mourns in anticipation of the lost object, but he keeps it as part of the psychic life, a highlighted absence. There is, in this absence, a possibility of insurrection against social mores. But as Judith Butler claims, there is a fundamental ambivalence at the heart of all melancholic agency.9 Aesthetics pre-empts critique. It censors it. Moves it into paradox and irony. But we do not see this modulated form here, where agency is both social and psychic. Boccaccio makes it an either/or. He opts in favour of the status quo. In our time, killing off critique clears the way for a writer’s psychic survival, but at the same time, there is a penalty for not turning aesthetics into resistance. There is a residual critical urge, which both fuels and challenges creativity. The fictional essay, or the essayistic fiction, I think, is a form that evolved out of this melancholic tension. Boccaccio’s work, I would suggest, was an early manifestation of this process. It found expression in Hamlet’s contradictions two and a half centuries later, in the development of a literary form known as the ‘self-address’, but at this moment, in the mid-fourteenth century, the representation of melancholy remained a dissatisfying play within a play in which the allegory, the critique and the resistance missed their mark.

While preferring social existence to subjection, external power to individual agency, Boccaccio was unable to represent rebellion. Health for him, meant the acceptance of conventional social roles. Yet he had Nastagio overturn all that at the first banquet. There, it was a signal of catastrophe. Boccaccio began with love, melancholy and excitement, and ended with the loss of his writing through a lack of spleen. Nastagio got the girl, but love was hardly guaranteed. It was an impoverishment, not an act of narcissism. It is the non-lover that turns down change, not taking any risk in finding a critical or artistic solution. As Anne Carson writes in Eros the Bittersweet, ‘The non-lover…is secure in his narrative choices of life and love. He already knows how the novel will end, and he has firmly crossed out the beginning.’10 The creative ‘elsewhere’ is terminated.

But those of us who still fall ill through lovesickness, who still risk loss, who still rage against uneventfulness, will always cling to our neurosis, held between Nastagio’s arrested motion and our own wild writing. In this case, melancholy is both the medicine and the poison, a risk that has to be negotiated in any form of endeavour linked to aspiration and ambition. We write the writing disease. And we write because we love our symptom.

- See Julian Jaynes, The Origin of Conciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind (London: Penguin, 1993.)

- Wolf Lepenies, Melancholy and Society, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1992) p70.

- La Fiammetta, trans. James C. Brogan, comments by John Addington Symonds (1907, Project Gutenberg e-books, 2003).

- Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror, (New York: Columbia UP, 1982), p207.

- R.K. Merton, Social Theory and Social Structure (New York: Free Press, 1968.)

- Lepenies, p4.

- Quoted by Roland Barthes in The Pleasure of the Text, trans. Richard Miller, (New York: Hill & Wang, 1975), p5.

- Paul Carter, Repressed Spaces: the poetics of agoraphobia, (London: Reaktion Books, 2002), p71.

- Judith Butler, The Psychic Life Of Power, (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford UP, 1997), p18.

- Anne Carson, Eros the Bittersweet (Illinois: Dalkey Archive Press, 1998) p150.