On writing Carpentaria

Where did the idea for Carpentaria originally come from? I don’t remember exactly. A friend once said to me while we were looking at the Gregory River in the Gulf of Carpentaria that the white man had destroyed our country. He pointed to the weeds growing profusely over the banks – burrs, prickles and other noxious introduced plants grew everywhere. It would take decades to eradicate the past decades of harm to this otherwise pristine environment. Tangling invasive vines grew here and there, smothering the slender young trees that are Indigenous to this savannah-zoned country. What he said was true, but what I saw was the mighty flow of an ancestral river rushing through the weeds, which were only weeds fruitlessly reaching down into the purity of this flowing water. The water rushed past the natural vegetation of ancient paperbarks, palms and fig trees that lined the river bank, and through the ancient serpentine track it had once formed while it continued racing forever forward, coursing its way to the sea. The river was flowing with so much force I felt it would never stop, and it would keep on flowing, just as it had flowed by generations of my ancestors, just as its waters would slip by here forever. It was like an animal, very much alive, not destroyed, that was stronger than all of us. The river reminded me of the Rainbow Serpent that travels throughout the country and across our traditional lands. Perhaps my seeing his skin sparkle in the clear bright sunlight over the Gulf was a present from the country. Perhaps it was then, at that moment, realising the largeness of standing where countless generations of people whose ancestry I share would have left their footprints, that I decided I wanted to return something of what I have learnt and to continue the story of this country of my forefathers. So in a very small way, I would like to think that Carpentaria is a narration of the kind of stories we can tell to our ancestral land.

For a long time while I was exploring how to write Carpentaria, I tried to come to some understanding of two principal questions: firstly, how to understand the idea of Indigenous people living with the stories of all the times of this country, and secondly, how to write from this perspective. The everyday contemporary Indigenous story world is epic, and although not entirely answering my questions, I feel comfortable in saying that our story world follows the original pattern of the great ancient sagas that defined the laws, customs and values of our culture. The oral tradition that produced these stories continued in the development of the epic stories of historical events, and combining ancient and historical stories, resounds equally as loudly in the new stories of our times.

Thinking about our stories in this way helped me to decide that Carpentaria should be written as a traditional long story of our times, so the book would appear reminiscent of the style of oral story-telling that a lot of Indigenous people would find familiar. I hoped that the style would engage more Indigenous readers, especially people from remote locations, to be readers of this book either now, or in the future, or perhaps at least, to be able to listen to a reading of the book. I felt a sense of having followed the right track when David Gulpilil confirmed my belief about how we tell stories when in narrating the film Ten Canoes he said that a good story will take time to tell, and that some stories will take several days to be told.

All the time I was writing Carpentaria, I felt that I could not afford to waste time writing books while there continues to be so much urgent work to do in our communities, or more battles to fight over the high levels of ignorance fostered by this government in particular about Aboriginal rights in this country, and from this sorry state of affairs, the deterioration and destruction of Aboriginal culture. This argument about guilt over taking time out to write I was having with myself, was played out with another argument: If I was to write this book, I knew I had to do it right and it would take time. There are not many people in our Indigenous world who are given the time or space to write a novel. These arguments drove me to set higher standards of what I should expect from myself, from which grew a phenomenal challenge that resonates in some way with something that Patrick Dodson recently said – a day does not go by without hearing of something that is challenging and confronting to us and demanding of our attention. Perhaps too, the drive in the Indigenous world to endlessly accomplish more, is equally the internalised consequence of being members of a people who are so scrutinised and unvalued, and the by-product of the extreme pressures of oppression and relentless, ongoing colonisation.

Most of all, I wanted to reach above the extremities of our capture by trying to portray our humanity as people who are capable of having great and little thoughts that are constantly being analysed and internalised in the Indigenous state of mind. I thought by writing in this way, I might contribute something to disrupting the stagnating impulse that visualises the world of Aboriginal people as little more than program upon countless program for ‘fixing up problems’. Surely, we are more than that.

The first challenge of writing a novel capable of embracing all times, was to find a way to develop a work of fiction which would portray the reality of the Indigenous world differently than in the context of how novels might normally be written and published in Australia today. The struggle I had was how to come to terms with the fact that this fictional work could not be contained in a capsule that was either time or incident specific. It would not fit into an English, and therefore Australian tradition of creating boundaries and fences which encode the development of thinking in this country, and which follows through to the containment of thought and idea in the novel.

I wanted the novel to question the idea of boundaries through exploring how ancient beliefs sit in the modern world, while at the same time exposing the fragility of the boundaries of Indigenous home places of the mind, by examining how these places are constantly under stress and burdened with threat, and often forced into becoming schizoid illusions of our originality. I wanted to examine how memory is being recreated to challenge the warped creativity of negativity, and somehow becomes a contemporary continuation of the Dreaming story. The fundamental challenge I wanted to set myself, was to explore ideas that would help us to understand how to re-imagine a larger space than the ones we have been forced to enclose within the imagined borders that have been forced upon us.

I turned elsewhere to try to understand how to configure the history I know and what I understand of our realities.1 Carlos Fuentes, the South American novelist, once said that all times are important in Mexico, and that no time has been resolved. His is a country of suspended times. As Fuentes explains: ‘the European author writes with a sense of linear time, time progressing forward as it both directs and assimilates the past. Even the great literary and philosophical violations of purely lineal continuity – Vico’s corsi e ricorsi, Joyce’s vicocyclometers – presuppose that a linear time does exist.’

Although some of the greatest European artists such as Picasso, Braque, Ernst, Bunuel, Joyce, Kafka, Broch, Lawrence, Akhmatova made dazzling attempts to discover the forgotten memory and imagination of Europe, ‘Their warnings were timely but went unheeded…Europe became the stage for the most brutal – because less expected, less rationally forecast – of all holocausts.’2

Another view of time, examined by Stephen Muecke, an Australian theorist of modern Indigenous expressions of self, suggests that there is in Indigenous philosophy a layering of ancient forms and imaginative inventions that oscillates between the ancient and the modern.3 Or, is there a sense of instability about time that has to be remade by the people and its leaders in overcoming oppression? Edward Said posed this question, pointing to the shifts between popular and formal speech, folk tale, and learned writing in the great cycles of poetry of W. B. Yeats.4

W. G. Sebald’s examination of time in the literature of Second World War victim of persecution, Jean Amery, refers to how, when the thread of chronological time is broken, background and foreground merge, and how the experience of terror dislocates time, the most abstract of humanity’s homes.5 The French-Caribbean writer and philosopher Édouard Glissant in his Poetics of Relation describes the dialectic in Caribbean reality as the balance between the present moment and duration. Looking inside this reality, Glissant does not see the ‘projectile’ reality of a coloniser. His Caribbean is a non-projectile imaginary, mingling centuries, and continuing through the whorls of time.

Mary Graham, the Australian Indigenous writer, has explained that there is a similar non-linear sense of time for Aboriginal people with the idea of beginning/middle/end being a foreign concept.6 Mythical Ireland also gave precedence to the poetic truth of spiritual beliefs rather than historical fact, because ‘the benefits of poetry can be more widely distributed in time and space’.7 Finally, James Baldwin, the Black American writer, notes that, ‘The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do. It could scarcely be otherwise, since it is to history that we owe our frames of reference, our identities, and our aspirations.’8

My new novel Carpentaria attempts to portray the world of Indigenous Australia as being in constant opposition between different spaces of time. Time is represented by the resilience of ancient beliefs overlaying the inherited colonial experience, which sometimes seems nothing more than hot air passing through the mind, while the almost ‘fugitive’ future is being forged as imagination in what might be called the last frontier – the province of the mind. A similar concept is identified by Brian Friel, one of the literary founders of Field Day in Ireland along with Seamus Heaney and Seamus Deane.9

Most of all, Carpentaria was written with the desire to create a work of art. Every word and sentence was worked and reworked many times to give authenticity to the region and to how people from that region with bad realities might truly feel and dream about impossibility. This authenticity, of how the mind tries to transcend disbelief at the overwhelming effects of an unacceptable history, could be understood as bi-polar: it’s there and not there. When faced with too much bad reality, the mind will try to survive by creating alternative narratives and places to visit from time to time, or live in, or believe in, if given the space.10 Carpentaria imagines the cultural mind as sovereign and in control, while freely navigating through the known country of colonialism to explore the possibilities of other worlds.11

Parallel to this aim of portraying the sovereignty of the mind was another, to try to create in writing an authentic form of Indigenous storytelling that uses the diction and vernacular of the region. Al Alvarez, in The Writer’s Voice, warns that in writing you might hear a voice coming from within yourself which you might not like: ‘The authentic voice may not be the one you want to hear.’ But if you listen to the voice and its rhythm, then the style will come with it, and once that is understood, Alvarez advises, ‘You can’t use the wrong words.’12 The work that resulted from this method of contemporary Indigenous storytelling has a visual, descriptive form in the way its stories are told. However, the written form is also visual in that it looks something like a spinning multi-stranded helix of stories. This is the condition of contemporary Indigenous storytelling that I believe is a consequence of our racial diaspora in Australia. The helix of divided strands is forever moving, entwining all stories together, just like a lyrebird is capable of singing several tunes at once. These stories relate to all the leavings and returnings to ancient territory, while carrying the whole human endeavour in search of new dreams. Where the characters are Indigenous people in this novel, they might easily have been any scattered people from any part of the world who share a relationship with their spiritual ancestors and heritage, or for that matter, any Australian – old or new.

The novel is narrated by replicating the story-telling voices of ordinary Aboriginal people whom I have heard all of my life. At the same time, I have been fortunate to have worked for a long time with some of our most brilliant Indigenous creators of stories from across the country. I have also been very lucky because wherever I go, other Indigenous people know I am a writer, and they have liked to tell me stories, and because it is obvious I really like stories, we have devoted many hours in the day simply to enjoying each others’ stories. In addition, I have always worked practically with other Aboriginal people, on major concerns, in either a networking or communications role at the community level, where I have listened to some of our best Indigenous voices intellectualising, describing, insulting or joking while they say just about anything they like about either themselves, or anyone else in this country from the Prime Minister down, to an ant passing over the ground. There are some Aboriginal people who will shower all those around them with wisdom with every breath they draw, while others make you weep or laugh so much, you want them to leave you alone. There are some you can actually see robbing the air from the day.

One can learn a lot from Carlos Fuentes, who writes ‘that the body and the soul of a novel are its language and imagination, not its good intentions: the conscience that the novel alters, not the conscience that the novel comforts.’13 I tried to be careful not to create a political manifesto out of a whole raft of concerns we have, but instead, to tell a story in such a way that the novel would somehow be like a narration to the natural world. The idea of the novel was to build a story place where the spiritual, real and imagined worlds exist side by side. The overall aim of the novel was to create a memory of what is believed, experienced and imagined in the contemporary world of Indigenous people in the Gulf of Carpentaria. My hope was that the novel would allow a space where Indigenous heroes are celebrated.

I also wanted to portray Indigenous heroes caught up in monumental situations such as I have seen practically all of my working life, so I went looking inside the full box of complexity of the contemporary Indigenous world. The idea struck me that if I were to tell a story to our people, I would also be telling a story to our ancestors. With that in mind, what would the story look like? The book then started to be written like a long song, following ancient tradition, reaching back as much as it reached forward, to tell a contemporary story to our ground. I hoped the book would be a celebration of our world and that it would be more substantial than the typical, pathological, paternalist viewpoint from which Australia typically portrays Indigenous people – as pathetic welfare cases unable to take care of ourselves, and at worst, as villainous rip-off merchants. Again, Carlos Fuentes, who learnt a great deal about heroes who ignore reality by chasing dreams in Don Quixote, argues that one way of seeing Latin American history, is through the use of history and myth, as in Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, which he sees as ‘a pilgrimage from a founding utopia to a cruel epic that degrades utopia if the mythic imagination does not intervene so as to interrupt the onslaught of fatality and seek to recover the possibilities of freedom.’14 Fuentes believes that the novel is more than reality, it creates a new time for readers, ‘where the past becomes memory and the future, desire…The novel expresses all the things that history did not mention, did not remember, or suddenly stopped imagining.’15 This is what I wanted to reach for, to achieve, because I think it is important to at least try to write something down of ourselves of what has been unwritten, so as to affirm our existence on our terms.

I wanted to write a book that tried to examine a place of enormous energy in Australia, to understand why its energy was so concentrated in a landscape of flattened claypans. Why did this country feel more vibrant to me than anywhere else in this country? Was it the claypans, seascapes, twisting ancient rivers of fresh running waters that flowed north to the sea, or the yellow tidal waters that flowed back inland? Or perhaps, in some special way, I related to the vegetation that was either spinifex-covered plains, or black soil grasslands. After all, my father was a cattleman who, I can imagine, had a passion running in his veins for Mitchell grass and black soil plains. Or, was it the oasis: the contrasting lush fruiting trees locked in the bottom of red rock ranges beside the river where my great-grandmother, grandmother and mother had grown up? This country and its seasons of heat, rain and mud could pull at my conscience. It could make me travel long distances just to be there. I always feel it calling. Sometimes it has great need, more than I can give. And this place creates so much love and yearning, and raises questions I might find it would be easier to forget.

This country had grown huge in my mind from the dreams of my childhood. The dreams came from the wonderfully strange stories I was told as a child by my grandmother. She was similar to the mother of André Brink’s Praying Mantis, the opening lines of which are: ‘Cupido Cockroach was not born from his mother’s body in the usual way but hatched from the stories she told.’ Many were not stories at all but just the way my grandmother normally talked. She spoke about things in such a way that I was left to create images of what was otherwise invisible of places, people and things. Of what could only be imagined. A person could always be something else, and once you are told of another way to see someone, you will always see him or her differently. And so, a tree was not just a tree. It could also behave very strangely if it wanted to. It has taken me a lifetime to understand the potency of these stories given as a gift, just as she had received them from our ancestors. I do not think it is right for me to ignore stories that have other ways of looking at the world. She chose stories about the kinds of ideas that would forge an anchor in her traditional country. In my lifetime, I have learnt many other stories about our family that my grandmother did not tell me. I know some of the best and the worst of our history. She chose what she wanted remembered. Perhaps intuitively, perhaps intentionally, she understood that the stories she did not want to tell could not provide a strong anchor. Indeed, they were the stories to create destructiveness. I have found the anchor she passed on has stood firm in life. It has weathered stormy patches as firmly as it has stayed steady in the calm.

The book needed the right voice and rhythm. I wanted the reader to believe in the energy of the Gulf country, to stay with a story as a welcomed stranger as if the land was telling a story about itself as much as the narrator is telling stories to the land. From the start, I knew Carpentaria would not be a book suited to a tourist reader, someone easily satisfied by a cheap day out. I wrote most of the novel while listening to music – I have an eclectic taste that roams around the world collecting a mixture of traditional, classical, new world, blues and country. One of my intentions was to write the novel as though it was a very long melody of different forms of music, somehow mixed with the voices of the Gulf. The image that explains this style is that of watching an orchestra while listening to the music. Within the whole spectacle of the performance, fleeting moments occur, in which your attention will suddenly focus on the sudden rise in the massiveness of the strings, horns, or percussion. This is what happens with this story as it moves through all of the diversity in the mind-world of the water people who are its main characters, descendants of Australia’s original inhabitants. At this level, the novel is about the movement of human endeavour, water, weather, fish and plants, while all around, the orchestra is surrounded and attacked by wild stories that have been provoked by its symphonies, which is the sound of the music made by the very thought of placing you in their domain.

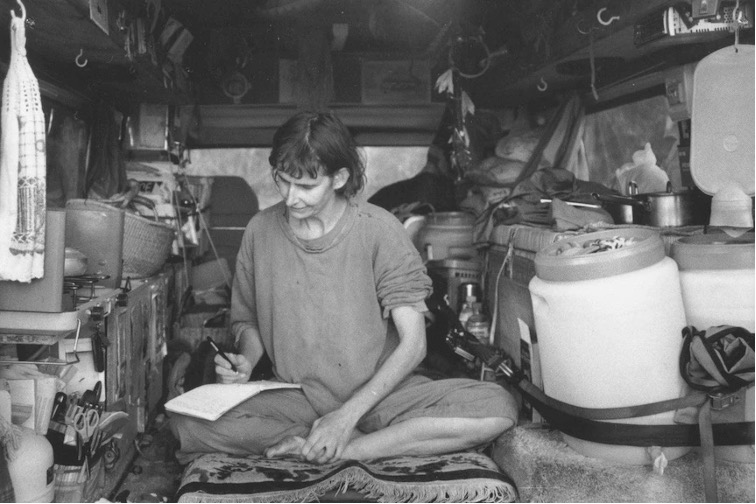

The musical tone in the narration really belongs to the diction of the tribal nations of the Gulf. It is a certain type of voice that is unique to the Gulf region, just as there is a similar but different style of Aboriginal voice on the other side of the country, in the Kimberly region of Northern Australia. In the end, after a long struggle I had with myself over how this novel should or should not be written, I chose to try to recreate the voices and tone of the old storytellers of the Gulf. It took several years to write this book and in the process, I destroyed earlier drafts because of my dissatisfaction with the narrative style, until one day in Alice Springs I found the answer to the problem. This happened while I was walking home from town across the footbridge over the Todd River. I heard two old men, elders of their country, who were deep in conversation, talking about how life in general was finishing up for them.

I remembered hearing stories told in this tone of voice throughout my life, and I remembered once reading about Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s epiphany when he discovered how to write a novel he had carried around in his mind for a long time. Marquez knew the only way to write One Hundred Years of Solitude was to believe in it. He had originally tried to tell the story without believing in it and it failed him, until he discovered that he had to believe in the story by using the same tone and expression with which his grandmother had told stories, with a brick face.16 The stories of Aboriginal people are similar to those of South America, Europe, Africa, Asia or India. The old storytellers of the Gulf country, or Indigenous storytellers in any other part of Australia, could also be likened to Marquez’s grandmother telling incredible stories with a deadpan look on her face. Such stories could be called supernatural and fantastic, but I do not think of them in this way.

I was often told as a child not to listen to my grandmother’s stories as she was filling my head with rubbish. I have since learnt that these are stories of spiritual beliefs as much as the beliefs of the everyday. It comes from the naturalness of being fully in touch with the antiquity of this world as it is now, and through this understanding, an enabling, to understand more broadly the future possibilities. These stories are about having a belief system and principles of the right and wrong way to live. It is these things that have firmly stood by the oldest race of people on earth and allow many of our people to uphold the country and care for the land. So I knew I had to write the novel in a tone of voice that felt comfortable talking about all manner of things that were happening in the everyday life of the people of the Gulf.

I also knew I would pay a price for my decision to write a novel as though some old Aboriginal person was telling the story. I think what I feared most was that this kind of voice and style of telling would be flatly rejected in Australia. Every day I was writing the novel, I would begin the day by arguing with myself about how a manuscript written in this voice was taking a big risk. I knew that by using a story-telling narrative voice in a language that was as much my own as it is of Aboriginal people in the Gulf, I was setting myself up for failure. It felt a bit like Seamus Heaney’s idea of the ‘Spirit Level’. I have always created some difficulty for myself by sticking to a principle when the winds are blowing a gale in the other direction. I knew that the principle of what I believed to be the legitimate way to present this story could cost me dearly. The manuscript might never be published. What then? Could I justify taking so much time to write a novel that would be rejected because it did not conform to the status quo? Every day was the same. I went through this crisis of arguing with myself about what I was doing, the risk involved, of perhaps eventually having to archive the manuscript from at least my own destructiveness in the offices of the Carpentaria Land Council. Always, I found it was impossible for my conscience to accept the idea that there was an easier way of writing the novel.

I could find no reason to write history, in the sense of drawing on historical incident, when all times are important and unresolved. Carlos Fuentes had originally outlined this understanding in relation to his traditional land of Mexico. The Indigenous world is both ancient and modern, both colonial experience and contemporary reality, and the problem right now for us, is how to carry all times when approaching the future. Eduardo Galeano explains that in his work Genesis, what he hoped to do was to, ‘contribute to the rescue of the kidnapped memory of all America, and to speak to his land [Latin America]…to talk to her, share her secrets, ask her of what difficult clays she was born, from what acts of love and violation she comes.’17 Most of all I did not want to write a historical novel even if Australia appears to be the land of disappearing memory. I felt there were enough writers already knocking on the door of history. I could see no point in using history as the legitimate place for a writer of fiction to retreat to from the reality of a dogged rational world, to explore their dreams, strange ideas, or creative strengths.

I have had to deal with history all of my life and I have seen so much happen in the contemporary Indigenous world because of history, that all I wanted was to extract my total being from the colonising spider’s trap door. So, instead of picking my heart apart with all of the things crammed into my mind about a history which drags every Aboriginal person into the conquering grips of colonisation, I wanted to stare at difference right now, as it is happening, because I felt the urgency of its pulse ticking in the heartbeat of the Gulf of Carpentaria. The beat was alive. It was not a relic. It was not bones to examine. It did not come from the dead world of academic expressions of identity or native title. The beat I heard was stronger and enduring even while tortured and scarred through and through. The beat belonged to the here and now. And the story to be told, it does not only come from colonisation or assimilation, or having learnt to read and write English, or arguing whether people with an oral history should write books, but is sung just as strongly from those of our ancestors who wrote our stories on the walls of caves and on the surface of weathered rock.

The seeds for novels are small and have to be harvested carefully. Many of these seeds cannot be captured on a mind that has edges of polished slate. What chance did anything have to grow? The seeds would lightly fade away, disappearing from memory before they were given the chance to take root. In this way Carpentaria had several false starts. I had to learn that inspiration will not grow on the surface of any mind too hardened by the battles like those we were having over mining. I felt that all roads were closed and had formed narrow un-welcoming paths over steep impassable obstacles. Sharp jagged edges reached out like sharp claws. This was how my mind had transformed itself, joining with the battlelines set up in the Gulf, with the arsenal of weapons our thinking could fire into the political fray. But even warriors of the Gulf must plough the fields that nurture the spirits; I had a lot to learn if I wanted to plant the seeds of the novel. I had to learn that nothing would grow until the terrain was pliable enough, and fertile enough, for the ideas I had been given to germinate. Even then, the crop required special care before the novel would ripen.

I found I had to learn how to care for the seeds I was given. I will try to explain. When the Waanyi people were contesting the development of the Century Mine on our ancestral domain of the southern highlands of the Gulf of Carpentaria, a large number of our people were camping in the Lawn Hills National Park along with numerous others from our neighbouring tribal nations who would also be affected by the plans to build this multinational mine – the biggest of its kind in the world. I listened to one of our major spokespeople saying with a proud heart, that he could personally stop the development of the mine. He explained how he could stop the mine in a really inspirational speech, of the kind that carries you away, to believe in him, that anything in this world is possible if you put your mind to it. He said he would simply throw broken glass bottles on the road and nails that would slash the tyres of the mining trucks. He said it would be easy. He further explained that no one would ever be able to find him in the Gulf of Carpentaria because he knew every square inch of it like the back of his hand. I felt his confidence. We all believed he could. We felt safe, the hundreds of countrymen and women of all ages who had travelled enormous distances to be involved in our protest. We were camping together on our ground. You could feel the embrace of our ancestors. It might sound hard for anyone with what is called a rational mind to believe that someone could smash the tyres of any of those 380-ton haul trucks loaded with up to 255 tons of ore that are now constantly on the move, working non-stop at the mine. But the Gulf is full of the belief of making what might seem impossible possible. It is this level of belief, of working with your own mind, where all things become possible in a different reality, from thinking for the land, of being the good caretaker for the land that the spirits would stand by you. Perhaps he was looking into the future and saw his spirit. At a level of belief that is easier to comprehend, there was no doubt that this senior traditional landowner in the Gulf could disappear in his own land if he wanted to. He, and others, could cut tracks through hundreds of kilometres of floods, or go to places in the sea, or walk off empty-handed into the bush with their babies, on journeys that would ensure their children would grow up learning the same things about the land.

In contrast to Indigenous spiritual beliefs, I also wanted to demonstrate in this novel that other people have strange ideas and belief systems about who and what they are. This is true whether they originated from British stock, or had come from any of the other races of people in multi-cultural Australia. I also carry in my heritage the remnants of a Chinese cultural background, and what I believe I have of an Irish ancestry, which makes me, I am told, the kind of person that might be mistaken as a native on most continents. When I read the fine Chinese writer Chi Zijian’s Figments of the Supernatural, I also see another side of the ancestral stories from my grandmother. Or, if I look at Michael Demes’ Mythic Ireland, I wonder what I might have learnt from my father’s family had I known them, and what of them I have inherited.18 I have often thought about how the spirits of other countries have followed their people to Australia and how these spirits might be reconciled with the ancestral spirits that belong here. I wonder if it is at this level of thinking that a lasting form of reconciliation between people might begin and if not, how our spirits will react. These are just some of the questions I had tried to form and to begin answering in the writing of Carpentaria. What songs should be sung in recognition of our national collectivity?

Several characters, Norm Phantom, Mozzie Fishman, Elias, Joseph Midnight and Angel Day were imagined from dreams, or from someone in the Gulf telling a story, or developed themselves on a long walk along the Todd River. These characters are like the Dons and Queens of Cervantes’ Don Quixote. We have Indigenous people like Quixote and Sancho Panza. I have learnt much about bravery in the Gulf from people like Murrandoo Yanner and Clarence Waldon who were the inspiration I needed to write a book that celebrated our heroes. In the journey of writing the book, these characters never abandoned ship, but demanded that I learn what they could do if I wanted to write about them. They were hard teachers and I can find similarities in the real world where most Indigenous people are more skilled than I would ever be at sea, to survive in a storm, or to track the stars, or catch fish. I often had long discussions long distance on the phone to people, but particularly Murrandoo, discussing tides, weather, storms and fishing. I feel honoured the characters gave me the chance to learn more about what it should mean to have my heritage.

One other important seed of thought I was given for the novel came from witnessing the deterioration of relationships between people in the communities of the Gulf from the negotiations to develop the Century Mine. The so-called native title negotiations forced people to choose between the intangibles of the future in a hostile environment that was at best patronising, and at worse, dominating, threatening, devious and cruel. In the fast-tracked negotiations, Indigenous leaders were not seen as equal in the non-Indigenous world of competing egos, but were often viewed as nothing more than ratbags, to be condemned. The people of these affected communities had very little, owned nothing but enormous poverty, but they were being bombarded by a rich multinational mining company that was backed absolutely by the state. These communities were given little choice but to argue with each other, and forced to choose how to hold on to fragile cultural interests, from a sale price that was a pittance in the scheme of things, just so that the vast interests of the company could proceed. From the side on which I was standing, it was like being in a place where a bomb had exploded, and those left in the rubble, knew that they could not depend on any real support from anyone in the social and cultural devastation they could see was their destiny.

When I look at the novel it is like seeing a myriad of ideas that have created the same thing: islands. I could have been writing about lonely termites’ nests, humanised, sitting in the wilderness like islands. Any other part of Australia would have given a similar result. If you could fly above the pages and perhaps see the whole sea of words as one inclusive idea as I often do when I dream words, you would see the direction of where the book was always headed. All the main characters of this book are like islands of self-sufficiency that act alone. They are islands created from their own ideas. The book asks what becomes of the islands we have created, of communities, our places and ourselves. An island can easily destroy and remake itself from its own debris. The realisation of this view became very clear to me recently when I discovered the photography of the Sulu Archipelago artist Yee I-Lann. In her series of Sulu stories she focussed on how to place a person, or incompatible persons fighting it out together on what must be the smallest islands above sea level of the hundreds in her archipelago.19 On a larger scale, I could see the similarities with the island mentality in Australia, and more strangely, how these influences have been carried into the novel. I have a theory that Carpentaria was imagined from an Australian heritage that has created disconnected islands of individuals, families, races, regions, beliefs, just as the continent itself is an island disconnected from anywhere else.

Just so! In such a scenario, and without settling for one explanation for the novel while others can be imagined, Carpentaria is the land of the untouched: an Indigenous sovereignty of the imagination. Just such a story as we might tell in our story place. Something to grow the land perhaps. Or, to visit the future.

Notes

- Craig San Roque, ‘On Tjukurrpa, Painting Up and Building Thought’, Social Analysis 48,2 (summer 2006): 148–72, argues that if we understand the configuration of Indigenous history, its geographical spaces, human relationship with the animal world, human phylogenetic history will help in the understanding of how it tells its story, what troubles the soul, and how psychic energies circulate.

- Carlos Fuentes, A New Time for Mexico (London: Bloomsbury, 1997), pp.13,16.

- Stephen Muecke, Ancient and Modern: Time, Culture and Indigenous Philosophy, (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2004).

- Edward W. Said, ‘Yeats and Decolonization’, in Terry Eagleton, Fredric Jameson and Edward Said (eds) Nationalism, Colonialism and Literature (Minnesota,: University of Minnesota Press, 1990), citing Barbara Harlow’s Resistance Literature (New York & London: Methuen, 1987).

- W. G. Sebald, On The Natural History of Destruction (London: Hamish Hamilton, 2003), p.154.

- Mary Graham, in Anita Heiss ed., Dhuuluu-Yala – Publishing Indigenous Literature (Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2003), p.33.

- Michael Dames, Mythic Ireland (London: Thames & Hudson, 1992), p.109.

- James Baldwin, ‘White Man’s Guilt’, in David R. Roediger (ed.) Black on White (New York: Schocken Books, 1998), p.321.

- Field Day asks Ireland to unlearn the Ireland that they know, and to receive new ways of thinking about it in analysing the present crisis of established opinions, myths and stereotypes that had become both a symptom and cause of the current situation. Brian Friel advances a ‘New Humanism’, where the fragmentation of value in the modern world, particularly in Ireland, ‘created conditions, far from destroying our powers of ethical self-determination, actually offers them new opportunities, new forms and contexts, new possibilities for reshaping the world and renegotiating in the ways in which, without completely abandoning traditional moral value may release us from the prison hothouses of worn out myths and stereotypes’ Retrieved 23 May 2005 from http://www.eng.umu.se/-lughnasta/-brian.htm

- Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation (2006). Glissant, long recognised in the French and francophone world as one of the greatest writers and thinkers of our times, is from the French Caribbean island of Martinique. He argues that the writer alone can tap the unconscious of a people and apprehend its multiform culture in order to provide forms of memory and intent capable of transcending ‘nonhistory’. His ‘nonhistory’ is the way he sees the Antilles as enduring an ‘invalid’ suffering imposed by history, and it will be through a writer’s relationship with the poetics of relation, which is a relationship with all of the senses of telling, listening, connection, and the parallel consciousness of self and surroundings, the key will be found to transforming mentalities and reshaping societies.

- Stephen Muecke, Ancient and Modern: Time, Culture and Indigenous Philosophy argues: ‘Modernity in the context of uneven development can thus have destructive effects. Carried out in the name of European modernity it has been seen as a civilising violence and criticised as involving a radical severing of the ties to community and place. People become atomised, alienated, exiled…Some Indigenous people are explicitly hostile to the ideas of rapid change and abandonment of the past that comes with modernisation and modernism’ (p.149).

- Al Alvarez, The Writer’s Voice (London: Bloomsbury, 2006), pp.29,43.

- Carlos Fuentes, This I Believe (London: Random House, 2005), p.184.

- Carlos Fuentes, Myself with Others (London: Picador, 1988) p.190.

- This I Believe, pp.178-9

- Sean Dolan, Gabriel Garcia Marquez (NY: Chelsea House, 1994), pp.95–6.

- Eduardo Galeano, Genesis (London: Methuen, 1987), p.xv.

- Chi Zijian, Figments of the Supernatural, trans. Simon Patton (Sydney: James Joyce Press, 2004); Michael Dames, Mythic Ireland (London: Thames & Hudson, 1992).

- artconneXions, Goethe-Institut.