Alive in ‘Ant and Bee’

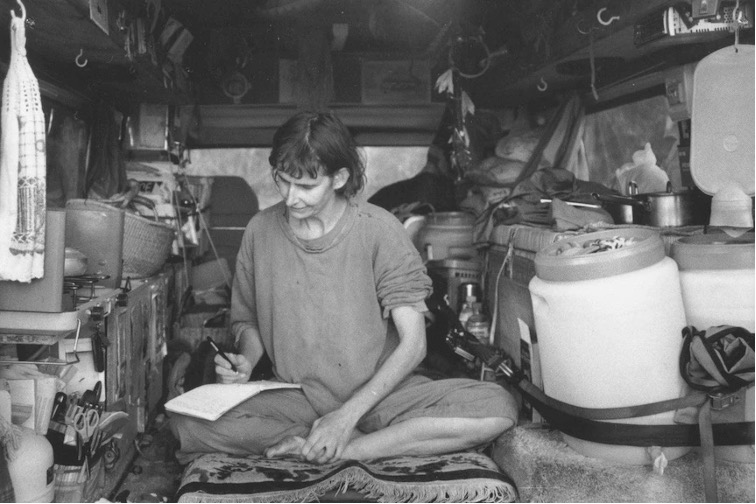

Gillian Mears. From the collection of Mike Ladd.

I am in the process of buying a thirty-year-old ambulance in 2004, sight unseen, and in the opinion of most people, I’ve gone crazy. Listening to Mr Bible from Homebush Motors in Sydney make his sales pitch on the phone, I think they might have a point.

‘Just wait till you put your foot down out on the highway. It’s like having a peach underneath. And the peach doesn’t bruise. An icon, that’s what you’ll be buying.’

It was not so long ago, that an invalid scooter had been my only transport. Even when I’d set it to ‘rabbit’, the fastest speed, the blind nun from down the road could overtake me on her cane. Before the scooter there was the wheelchair. In the winter sun of 2002, the spokes of its wheels cast shadows along the hospital patio in such a way that I couldn’t stop crying. I’d had a seven-year-long struggle to walk, due to a form of multiple sclerosis that defied diagnosis, but that wasn’t why I was being slid in and out of wheelchairs.

The open-heart surgery I underwent in 2002, following the emergency diagnosis of an infection in my heart, is like a penumbral eclipse of my life that can still seem incomprehensible. Why didn’t I get myself to hospital sooner, before I was so nearly a corpse? How could it be possible that in so fervently following the advice of a macrobiotic practitioner whose treatment banned any recourse to Western medicine, I became part of a calamity so huge I almost died?

There were reasons. Imagine, after a lifelong passion for physical activity, suddenly finding movement itself becoming a mystery. Imagine, at the age of thirty-one, beginning to stagger like a Kurt Vonnegut syphilitic. Next, horrible feelings running along certain stretches of your skin, as if this were where Peter Piper’s peck of pickled peppers had lodged.

As is common with multiple sclerosis, before diagnosis came many misdiagnoses. Everything from the trivial – my GP attributing my malaise to the effect of leaning on my elbow as I sat at my desk – to the extreme. The first MRI was to look for signs of multiple sclerosis but nothing was showing. Although no neurologist was convinced that my symptoms stemmed from an old horse-riding injury to my neck, pressure was intensifying that I must agree, the sooner the better, to major spinal surgery.

In my increasing alarm, I turned to the huge range of alternative health practitioners that anyone with an affliction in the twenty-first century might feel familiar with. I tried reiki, traditional Chinese medicine, holotropic breathing, reflexology and kinesiology. Under the directives of this or that healer, I drank disgusting molasses and soy-milk brews. I ate charcoal and seaweed. I fasted. I looked into colonic irrigations, iridology, numerology, Feldenkreis, Alexander technique, Bowen therapy, bone massage.

Again I consulted a range of GPs and specialists. Again I was scanned for multiple sclerosis. Again, no sign of any of the telltale scar lesions around nerves in the brain or spinal column. Vitamin B12 deficiency, syphilis, HIV, hepatitis C were also all ruled out. In the last MRI scan, the bit of osteoarthritis in my neck was neither better nor worse. A plump, small-fingered neurosurgeon diffidently suggested that a registrar could operate.

‘We could book you in within the month. We’d come in through the front of your neck and put in a self-drilling cage. Take out the bony deposits around C5. It might help. But only in terms of you not deteriorating. I’ve seen necks on ninety-year-olds in far worse shape than your own. Yet with none of your symptoms.’

A fortnight later, by chance, I met a horse-rider who’d had just such an operation on her neck. One operation had led to three. Her throat looked like the site of a chainsaw massacre. Some kind of permanent intravenous morphine drip only slightly numbed her pain.

I went home and, piling all my MRI scans and X-rays into a barrow, wheeled them out into a paddock to bury.

Apart from mental anguish I was in no actual pain, except from the financial. If I were to add up what I had spent on alternative health practices I could have had the deposit on two, maybe three houses.

Only Dr Seuss–style verse could properly convey some of the nonsense I was again forlorn enough to try. I was wrapping my middle in castor oil compresses. I was following the Fit for Life diet.

Eat thirty-two spirulina tablets three times a day. Cast out your demons. Talk to angels.

On the bicycle it was becoming increasingly impossible to pedal, I hurtled down hills with affirmations on my tongue. ‘Every day and in every way, I’m getting better and better!’ Except I was not. On certain days the creeping sensations began entering my eyes and I feared I was starting to go blind with something Western medicine had no name for.

Then I encountered the healing modality known as macrobiotics. At first it seemed a wise philosophy, shot through with a spare Taoist aesthetic. After so much gobbledygook, I found it irresistible. I soon became the charismatic macro man’s lover and in my despair I helped to dig the doom that would overtake me two years on.

This had nothing to do with my walking mystery but was untreated endocarditis. My heart was infected. Five and a half months of physical agony and every new symptom gravely interpreted by my partner as my body being at last strong enough to detox.

After the ordeal my body has been through, how much easier seem the practicalities of buying the old F100 ambulance. As Mr Bible rants on, the afternoon breeze is causing the calico flourbag safety-pinned to the back of my old scooter to shift out and in.

‘And the prior owner used the ambulance for camping?’ I ask.

‘More or less mate. More or less. A bit of eggs and ham in the back but nothing the feminine touch can’t rectify.’

Much more than Mr Bible, it’s a line out of Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood, scrawled in texta on the flourbag, which I so long to believe. That ‘the unendurable is the beginning of the curve of joy’.

The ambulance is a gamble, I know, but not as big a gamble as staying motionless in Mary Street. Nothing chills me more than the thought of the institutionalisation that happened to my grandfather. Diagnosed at the age of twenty-two with the form of chronic progressive multiple sclerosis I’m living with, he eventually went blind. Just before he was put on the top floor of a hospice to die, they amputated both his legs.

This flat I’ve been renting on the Hoof Street–Mary Street corner, once such a sanctuary after open-heart surgery, has come to feel just like a smaller version of the Grafton prison diagonally opposite my bedroom window. The bricks of the flat resemble the worst Westons biscuits, adrift with flecks of inedible choc chips. On every side of me are frail neighbours in their eighties. When they kill ants in the patch of grass we share, fumes from the spray drift into my flat’s kitchen window.

As far as my eye can see, outside every neat house in every direction, stand red and yellow wheelie bins, ready for collection. It’s as if I’m stranded in some giant version of a board game too boring to play.

Something in me wants to scream. Needs to run.

In two and a half months of searching, the ambulance is the only camper I find to fit the budget of a writer living below the poverty line on a disability pension of $228 a week. Once I sell the little white car to which I graduated from the scooter, there might even be enough for refurbishments.

‘And it’s yellow?’ I check with Mr Bible.

‘Harpers Gold, Gillian. Harpers Gold.’

So that in the two weeks it takes to organise transport of the ambulance to northern New South Wales, I keep wondering whether it’s going to spangle in the way of that ex-girlfriend who danced topless up Oxford Street one Mardi Gras inside her replica of the Melbourne Arts Centre spire, or whether it will be more of a Christmas beetle gleam.

But the moment I see my ambulance coming through light autumn rain into a South Grafton service station, I realise the colour is that of Calyptorhynchus funereus, the black-tailed cockatoos that always scream upriver when people I love die. From a distance, my camper, loaded on the back of a transporter, is a faded, ochre-yellow wonder around which Astroboy-bodied Hyundais are stacked like matchbox cars.

Because I’m so scared I know already that I’ll call my camper Ant and Bee, after the Angela Banner books, which brought inestimable comfort through all the early years of my 1960s childhood.

‘Be careful,’ says the transport driver when the seatbelt anchor flies into my hand as I buckle up.

As I make my way into the heavy afternoon traffic burning south on the Pacific Highway, it’s incredible no police siren stops me. With no speedometer, no rear-vision mirrors, and windscreen wipers that don’t work, I take my maiden journey in Ant and Bee. I don’t care that I’m about to find out there isn’t a nut on the bolt holding the driver’s seat onto a piece of ply. So what that the camper conversion described by Mr Bible appears to be an esky chucked in the back and a bit of old foam ockie-strapped to the roof? All will surely be fixable.

On this first drive, how marvellous seem the bends integral to the eccentricity of the Clarence River Bridge. From my lofty new driving height, the old trees of Grafton have never been so golden. How fantastic, how safe, this great bonnet of yellow iron stretching out in protection. Ah, the headiness of the promise of aloneness; of finally being, afflictions and all, the solo driver of my own life.

The last time I crossed the Clarence River in an ambulance, the siren was screaming and I was almost dead.

July 2002, the coldest winter on record for decades. Any recollection I allow of it always rolls out like the present.

The eve of my thirty-eighth birthday.

An old friend, working that night shift at Grafton hospital, hears that a woman’s been brought in from Nymboida ‘and they expect she’ll die tonight’.

I have a fever of 41 degrees and veins so dehydrated that my arms turn black with bruises as the hospital staff search for a spot that will take a blood transfusion.

Acute endocarditis. An infection of the heart. Neither my macrobiotic partner nor I have ever heard of such a thing. As soon as the local heart specialist is convinced of his diagnosis, a succession of ambulances takes me to Sydney for surgery. Although I’m in a state of physical anguish I feel absurdly safe, as if now my belly’s full of hospital-issue, two-pack Arnott’s Scotch Fingers, all shall be well, my agony soon over.

Even though I’ve never really watched television medical dramas, somehow I feel that they’re part of my confidence; that surely this script of my own life is going to have a happy ending.

A streptococcal vegetation has been living off the mitral valve of my heart. In the absence of early detection by conventional medicine, it has become so vigorous, so mobile, that colonies are in my spleen and in both kidneys as well. The risk exists that at any moment a piece will ping off into my brain, causing a stroke big enough to end my life immediately.

If I survive the surgery essential to remove the main vegetation on my heart, grown as large as a four-centimetre long caterpillar, another operation might be scheduled to remove my all-but-destroyed spleen.

In the air ambulance to Sydney, a guttural note enters my sobbing. It was only twenty-four hours before, at midnight, that my macrobiotic knight errant, apprehending at last the gravity of my condition, had eased my lightweight body into his truck to take me to hospital. Half a year since the excruciating onset of the heart infection. Half a year since I’d seen any of my family or my old hometown of Grafton. Macro-errantry. Macro-lunacy. It was as if by living in isolation along a stretch of the wild Nymboida River, surrounded predominantly by all the classic texts of the macrobiotic lineage, that I’d dried out my brains and lost my wits. A kind of warped, twenty-first century healing version of Don Quixote. Almost a cult. Definitely a folie à deaux.

The dual decline of my body – multiple sclerosis followed by endocarditis – is a mystery I’ve yet to decode fully. One day I’ll recall all the bizarre facts. But not now. I don’t want to spoil taking my new home-to-be on this first drive.

Driving back through Grafton to my flat, I push the past out of reach, focusing instead on the 4/3 rhythm that the abandoned intercom system makes as it hits the windscreen.

I’m alive aren’t I? Alive in Ant and Bee, and the thin black steering wheel moves like a waltz in my hands.

My first task is to become an overnight petrol head. The intricacies of the internal-combustion engine are explained to me in that enthusiastic language of car-crazy boys. What better distraction from the past than craning over the bonnet or lying on my back under the chassis?

I discover who are the mechanics in my town with a relish for working on old Effies, as any F100 is affectionately called, and learn many things: when it might be necessary to put pepper into the radiator, how to clean spark plugs with a metal toothbrush, the miracle of WD-40 at work on ancient rust.

The mechanics are making the old ambulance sound. They’re as cordial as Darjeeling monks: I could weep with gratitude when the auto-electrician throws a piece of canvas over a stash of MS-induced incontinence products he’s had to uncover to get some wiring finished. The radiator man, without asking, rigs up the new air-conditioner with a bit of PVC tubing from his backyard. Only then does the unit, which cost more than the ambulance itself, blast cold air in the right direction. This is essential because, as is the case for many people with MS, the moment my legs grow hot my ability to move them drastically declines.

Next I turn my attention to the interior. To cull forty years worth of possessions so that they fit into a space no bigger than a bathroom is only a momentary challenge. ‘Jettison’ is becoming my favourite word. The more I give away, the more gleeful I feel. How fantastic to have a kitchen that fits into a red Coles shopping crate. How light my melamine bowl, cup and plate stacked like games in a toy box.

A narrow, sky-blue woollen carpet, afloat with white Tibetan cranes, doubles as my mattress and living area rug. Sitting cross-legged here, I can wash dishes, brush my teeth, reach for CDs, check my hair in the small circle of mirror on the wall, and not have moved a step. Underneath the ply sleeping-platform I store an axe, spade, blockbuster hatchet and campfire cooking tripod.

Painting the long cupboards that once held medical paraphernalia takes ten minutes and half a 250-ml tin of paint. They are the perfect height for holding kitchen canisters of pasta, rice, nuts and tea.

I’ve given notice at ‘Brickland’, and with only a fortnight left to go, each day is crammed with activity. I’m decorating now, removing my loveliest, luckiest little watercolours from their frames. Sticking them onto the cleaned ambulance walls.

Cloth gathered long ago in different countries makes beautiful curtains. How fast my life has gone, I think, fingering a square of African cotton from the 16th arrondissement in Paris. How young and strong I once was, able to walk miles in a day. My days are swifter than a runner. How can it be that now I’m more than forty, with legs that haven’t walked properly since the age of thirty? They flee away. They go by like skiffs of reed. Like an eagle falling on the prey. Maybe this’ll be the decade to finish reading my tatty bible, which in Ant and Bee always seems to fall open in my hands at the Book of Psalms, as if this is where my reading of it stopped as a child.

No matter how skeptically people view my plan, everyone’s rallying to help. If I sometimes have to pause, crouch down, it’s due to the love washing over me from my family and friends, like the waves of some magical sea.

The increasing sense that my ambulance has become a cubbyhouse on wheels – new radial Firewalkers, their treads black and deep – brings delight. From the iron ceiling trusses I hang an assortment of charms, each object full of secret and lucky histories.

At certain angles Ant and Bee conveys the impression of a stationery shop. What a simple happiness to plump out a cane basket with new glue sticks, five different kinds of tape, rubber bands, pencil sharpeners, paintbrushes and stamps. Favourite coloured nylon tip pens hang by their lids along one side of a cardboard box rigged to hold cutlery. In no time at all pens will outnumber forks, as if words are to be my main nourishment.

Later still I’ll come to appreciate that a roaming home means no cockroaches and no rodents of any kind. Soon, too, I’ll be relishing bucket-and-jug washes, my body like a baby in my own hands.

A camping shop has an aluminium table that will serve as my writing desk, and a determined friend finally finds the perfect chair. Folded, they both tuck up neatly between a 12-volt fridge and three 20-litre plastic drums of grain. But would Rilke, I can’t help but wonder, still advise his young poet to look into his heart and write? If the left cockle of the poet’s heart were made of carbon?

As autumn arrives, I can feel the valve’s artificial edge seated like a bit of meccano beneath my breast. It ticks as if made of tin, and sounds too small for my body. What if the neurocardiology researchers of the twenty-first century prove right and there is a brain in the heart? What might a new lover think when they hear the sound? Will the valve handle the accelerated beat? Will there indeed ever be a new lover for one limping around in a body of such obvious wreckage?

Now I perch with unbearable anticipation on the two long shelves built to run either side of the van. Which books, which stories, which poems will I choose to travel with me? Four dictionaries, heavier than firewood, find the first space, and then my old paperback thesaurus. Not because it’s ever been much use but because I like the smell of its thin yellowy pages, and the handwritten inscription of a sister whose gift it was when I turned sixteen. Tenderness is the sentiment that determines which old fictional favourites are chosen. Is there room for all my Randolph Stows? How about Virginia Woolf and Carson McCullers? I squeeze in a few equestrian classics and an assortment of poetry volumes I feel I can’t live without. I also find the remains of my childhood edition of 1, 2, 3 With Ant and Bee – a scruffy mascot for the glovebox.

The day arrives when, with no further funds left, I can hone my state of preparedness no more. As I cross the bridge one more time, I say goodbye to the town of Grafton that I’ve loved so deeply, sometimes loathed, and written about for most of my life. The Clarence, my own river Alph, seems afloat with more memories than any story can accommodate. Farewell, old dear town that helped bring me back to life. Farewell, old, dangerously compliant self, who very nearly allowed her own death.

Travelling to no deadline, and with no fixed route, I’m on my way to live in Adelaide. As my first cautious weeks go by, I recognise the Way described with such a mixture of comedy and pathos in Farid Ud-din Attar’s twelfth-century mystical classic, Manteq ot-Teyr, or The Conference of the Birds.

Even in the doggerel of the English translation I feel an enchantment, which is also connected to the beauty of my battered old Penguin paperback. The Persian miniature on the cover depicts a multitude of birds gathered by a decorative river. With as plucky a spirit as they can muster, they too are leaving the safety of their homes. Only with the assistance of each other, Attar’s spiritual allegory emphasises, will the birds find their way. His riddling tales often mock the solitary attempts of desert Sufis, wrapped up in dangerous self-importance. Unless, warns Attar, you can see divinity everywhere and in everything, including every human being, then you’re missing out on the mystery of the world.

For the first six months, though, once I’ve ascertained that even with MS the camping life is possible for me, I hide out alone in the state forests of north-eastern New South Wales.

In the bush I take respite from the inundation of people that occurs after you have almost died. Old trees and rain, starry skies and insects – these are the antidotes I crave. Frogs croaking, the songs of crickets, spiderwebs strung between fronds of lomandras. This is when my true recovery begins.

Moonlight can bring the impression that a galaxy of stars, a miniature Milky Way, is sliding into the tree closest to my camp. One morning, before light, my water bucket holds a reflection of the waning crescent moon at such a steep angle that the song of the first shrike thrush seems to touch its tip. To think that it was only due to catastrophe that I’ve chosen this way to live.

In order to avoid another medical emergency my van is rigged for safety not only with a two-way radio but also an EPIRB device that, if activated when I’m out of mobile phone range, instantly alerts an emergency centre and locates my exact position via satellite.

Life in these forest camps is calm and kind – my water dipper going in and out of a reed-rimmed wetland. Because I don’t set up in well-known, overused beauty spots, all is fresh, the energy untrammelled and not a Vodka Cruiser can or chewing-gum wrapper in sight. The insects don’t know how to bite and lizards are not afraid of me.

Every seven or eight days when I’m camping, I screw a small stone mill onto Ant and Bee’s back step. In less than an hour I have my flour for bread. A 25-kilogram sack of wheat berries costs less than five supermarket loaves. Dip a finger into fresh flour and it smells as alive as a little animal. Is there anything more peaceful or satisfying than turning flour into dough? This simple alchemy of sea salt, water and my own wild starter yeast; this dough forming like a head in my hands.

My balcony brush swish-swishing across the Tibetan rug is a rhythmic link to all the early morning sweepers of Asia and Africa, and even as far away as twelfth-century Baghdad. In The Conference of the Birds, one of Farid Ud-din Attar’s sweepers has just been given a bracelet sparkling with jewels from the king.

Who did Ant and Bee save? I’m always wondering. When it was used as an ambulance? Until 2002, my emergency year, ambulances had always been like fire-engines – an urgent wail for somebody else’s disaster.

‘Sorry,’ a man who used to drive ambulances in the 70s tells me in a caravan park laundry, ‘but your old ambo would’ve usually been heading for the morgue. Most people died.’

This, he claims, was mainly due to heart attacks, happening most frequently around eleven p.m., the body unable to cope with its last heavy meal. Ambulances back then carried little more than oxygen and a first-aid kit. Splints in the cupboard where I now keep my rolled oats and almonds.

‘Probably shouldn’t tell you this,’ says the ex-driver, ‘but one night we had a man who was smashed into smithereens. Come off from the thirty-third storey of a building in George Street. He was only young but we couldn’t lift him. No bones big enough left.’

Back in Ant and Bee I turn on the radio. Just in time to hear that the day before, a young Sunni man strapped on his bomb belt, packed with nails, to blow himself and seventy others up, just before breakfast Baghdad time.

My glumness deepens. Ud-din Attar’s anecdotes, often set in Baghdad, also tend towards bloody ends. Al-Hallaj, a Persian Sufi, was flogged, mutilated, hung on a gibbet and decapitated for his heretical pronouncement, ‘I am God and I am the Truth’. Then Ud-din Attar himself was purportedly beheaded.

Which-a-where, which-a-where. In the camp I choose for my first solo bush birthday, almost a year after setting forth, the air’s alive with small birds. Which-you, why-you, they sing. Weech you. Wheeech you.

Thinking back to turning thirty-eight three years ago, I try to cry but can’t. The air of this clearing is too limpid, the noises from the small circle of a wetland too strong for tears.

Why you, which you, cry the black-faced fly-catchers, sallying in the air after insects.

So here at last, just before I turn forty-one, will be the place safe enough to remember fully. The urgent need for this makes me grind flour fast for my next loaf of bread. In less than half an hour I’m done. I check the starter. Good. It’s very active, its bubbles rising and popping. In haste I form the dough.

Flouring its bottom and setting it in the sun to rise (it will take all of the bright day), at last I’m ready to allow the past to roll out like the present.

Like the Romans I believe memories are stored in your cor, in your heart of hearts. So in a sunny glade, lying on a blanket, I place my hands there over the vertical scar, to help let it be 2002 again.

In the few days lead-up to surgery my sister nips open the restricted red patient file and at my behest reads ‘Severely wasted, unwell lady, febrile, septic, with severe mitral regurgitation and acute heart failure. Limited movement due to extreme pain everywhere.’

From my hospital bed I weep at the sheer implausibility of how something as shining as macro-errantry has led me down a path this dark. When I dare a glimpse in the hospital bathroom mirror I think that if I were a wounded wallaby by the side of the road, I’d knock the life out of her with my car jack. When I’m weighed in a basket I’m 39 kgs. Naked I look like a concentration camp victim. My liver shutting down has lent my skin a dreadful, snakeskin-yellow hue. I feel stranded in a script penned by a horror writer devoid of skill.

That it’s my drastic love affair that has brought me to this point is part of my pain. After trying so hard. So no, I decide in front of the hospital mirror, I won’t look anymore into my Knight of the Sad Countenance’s face. I will avoid the appearance of my thighs, fallen like two twigs underneath the hospital gown. I won’t dwell on the ash my lover used to treat the bedsore that smells of death, there at the base of my spine. Nor on his absence from this bedside of extremity he so helped to create.

Instead I tune in to the sheer pageantry of life. The whole hospital’s a show on which I feast and feast, unable to take my fill.

Look! There go Dr Miriam Welgampola’s shoes again, so small, so elegant that surely elvin cobblers create each new pair in the night. What is the exact tragedy of the chain-smoking Kurdish Iraqi doctor with the smouldering good looks? How come his eye got blackened at the Coogee Bay Hotel? And the friendly tableau of night nurses munching on the lollies that fuel them through their shift. Such scenes are a call to life more potent than any painkiller.

Here come processions of precious friends carrying baskets full of the most marvellous food and drink. After two years wherein the eating of sugar was equated with shooting up heroin, I tune in to homebaked puddings.

Human flirtation comes next to my bedside. Oh the lovely flitterings of it over me as I lie inert, surrounded by beloved members of my family. My dark-haired sister – the beauty of her, dressed like an eighteenth-century gypsy, as her deep brown eyes meet the nearly black ones of the bodybuilding male nurse from the Philippines. My father too, laughing with happiness as he recognises he is indeed still attractive to the nurses.

Ah the light-hearted eddies across my shriven form, so that in the absence of fresh air, this is an almost greater tonic.

Finally there’s Dr Grant, the cardiothoracic surgeon himself.

‘Of all the doctors, he’s my favourite,’ declares my sister. ‘Thank goodness he’ll be performing the operation. Have you noticed his energy? He’s like a bull.’

Matador, I secretly think, with his elegant moustache, especially when he goes by wearing a surgical gown as dramatic as any cape.

When one of the students confides that Dr Grant is renowned for his surgery on the hearts of children, I make a point of looking at his hands. His fingers are a poet’s, long and pale. Due to my emaciated condition, the risks of open-heart surgery are high. Before I sign the permission form, I must be aware that I might die. But without this surgery my death is certain.

When the day of the operation arrives, my grief in saying goodbye to my colourful retinue is greater than all the towering floors of the ugly hospital. The ward’s grey dullness runs in time in me with Psalm 55. My heart is sore pained within me and the terrors of death are fallen upon me. Fearfulness and trembling are come upon me and Horror hath overwhelmed me.

Regret flows in me. So this could be the last landscape of my life, this desolate place full of suffering people? According to the Socratic aphorism, I can’t be judged to have excelled at philosophy because I haven’t practised for my death, for my dying, not at all. I’d always taken it as given that, in the style of St Francis of Assisi, I would die outside, on solid ground, on grass. Far into the future, when I was old.

As orderlies slide me onto the surgical trolley, something unwanted begins to happen. Psalm 55, which even through pain I apprehend as being suitably charged for the situation, is being shoved aside. Instead, Edward Lear nonsense verse. As soon as he saw our daughter Dell, in violent love that Crane King fell. Taking over my mind.

Oh no, if I have to have Lear, rather than any plangent prayer or segment from some ancient saint, can’t it at least be the Owl and the Pussycat? Please, God or whoever, I want the owl and the cat. The dance by the light of the silvery moon. I hate ‘The Pelican Chorus’. Pelican Jee! Oh happy are we, wading in on its great flippered feet. Ploffskin, Pluffskin, Pelican Jill, we think so then and we thought so still.

I never let anyone abbreviate my name to Jill. Now, due to a spelling error made on my admission, it’s as ‘Gorillian’ that I’m being wheeled down the corridor to the theatre.

Somehow my sisters reappear for a last kiss goodbye. She has gone to the great Gromboolian plain. And we probably never shall meet again.

I have said goodbye to everyone except myself. ‘Don’t be crying now,’ says the beautiful Irish anaesthetist, who also succumbed to my father’s charisma.

For the king of the cranes had won her heart with a crocodile egg and an ice-cream tart.

What if the Buddhists are right, and from your last conscious thought comes your next reality?

In a moment the needle will go in. Why hasn’t anyone mentioned God? Why did I stop praying when at the age of nine I lost my Book of Poems and Prayers for the Very Young, with the peaceful brown mare and foal on its cover?

My diseased heart will be exposed. The eyes of strangers will marvel at the extent of my gigantic mistake.

Was it an ice-cream tart or seaweed? Nori like mermaid’s paper? Mists from the yellow Chankly Bore are rising up to greet me and someone is about to saw open my sternum.

‘Oh yes,’ says Dr Grant on my first check-up since beginning to live in Ant and Bee. Almost a year of the camping life and I’m feeling fantastic. ‘I suppose I would’ve done that bit.’

‘With what kind of instrument?’ I wonder.

‘Well, it’s sort of a jigsaw.’ And as if he’s doing an ad for Father’s Day, his hands apologetically mime a few jumps of the tool. ‘Suitable for tissue, not wood,’ he proffers, to soften the reality. ‘And here, I did bring a valve for you to see. Worth about five thousand dollars.’

More than Ant and Bee’s purchase price. I look in astonishment at the piece of flim-flam lying in the palm of his hand. It resembles something found in the back of a stationery drawer, its function forgotten and impossible to guess. It’s a carbon ring of a size that would fit my big toe, rimmed in white with two thin semicircular flaps the colour of sunglass lenses.

I look back at Dr Grant, sitting a little sideways in his chair, his tie loose. He has the affectionate, crumpled air of a favourite nephew. It seems barely believable that those hands so at ease there in his lap are the same ones that trimmed away the remains of my mitral valve and then sutured one of these rings on into place. The same hands that scraped off the morbid bacterial carpet growing across the floor of my atrium.

Would they also be the ones responsible for the six shepherd hitch twists in the wire that put my sternum back together? The wire that I sometimes finger as I drive, the metal as hard as silver buttons just under the thin skin above my breasts?

For a moment the wish arises in me that across the wooden desk we could hold hands; fleetingly, just so that I could feel with my own fingers those that had known my actual anatomical heart. But he’s busy behind me now, checking with his stethoscope that he’s hearing the right rhythms.

‘You seem remarkably well. Pulse is seventy-six, which is pretty good. How have you managed that?’

I almost guide his gaze to the incongruous sight of my old ambulance amongst the ordinary vehicles of the city car park. The artist friend who printed the name for me on the original ambulance plate above the windscreen did so in a shade of blue and yellow that recalls bush wattle in bloom under a clear sky.

‘Well, just keep doing whatever it is that has you in such good shape.’

The Ant and Bee life, I want to exclaim. The most effective physiotherapy of all. Almost twelve months of living in such a way has brought unforeseen strength. I can feel the ripple of the abdominal muscles I’ve grown manoeuvring the F100, manufactured long before power steering.

At the door, although I give Dr Grant my most sincere thanks, how can they ever express my ever-ongoing and huge gratitude? Only a dance might convey my joy to him; beautiful bodies spinning like birds over faraway mountains.

Back in the bush, the lights of a plane crossing over my camp remind me of those that blink on and off in a hospital at night. In Dickinson Ward South after dark, in the interminable eight weeks following my open-heart surgery, there was no dancing and no joy. Some nurses were so saintly I’ll remember their faces forever; others were sadists I couldn’t run away from.

Beneath my nightgown I was a gory mess. If I could have spread out my arms I’d have looked like a dingo hung on a fence by a hunter. Pain rippled from the wound and lay so deep inside it could be assuaged by no painkiller. It took four weeks before I could sit up unassisted. Because my catheter had unwisely been removed, my bed was a river of urine. My legs swelled into tree trunks. Whenever I cried, which was often, it was with the open wish on my lips that I hadn’t survived.

There were two other beds in my ward. In one of them a man called Jim was also crying. He’d just found out that, actually, sorry, there’d be no heart operation for him because what the doctors thought was fluid was in fact the solid mass of a tumour bigger than anything they’d seen. I couldn’t believe that a team of young doctors were imparting this news to him with only a cotton hospital curtain between him and me.

The next day his dry humour kept him going through the phone calls. ‘Yeah, mate, two weeks…Nah, no operation…Two weeks. Wasn’t water round me heart but a great mother of a tumour. More life left in me fucken little finger than in me lungs.’

He was thirty-six, with four young sons. Each night, before Jim was transported to a hospice for the dying, he shambled in disorientation from one bed to the next, a personification of words from Emily Dickinson, of a ‘pain so unutterable’.

My sleeping pill always wore off at midnight, leaving hours to survive before the sight of the tea lady’s sneakers. ‘Help me, help me,’ I heard Jim calling, but nobody could.

My balance, which had always been precarious in the preceding seven years, was more deranged than ever after surgery. I had to wait three months for an explanation of this, by way of an MRI scan, which could not be done until my artificial heart valve was secure. In case the powerful magnets of the scan slurped it out of position, as jested the neurology team.

The MRI brought not only a firm diagnosis of MS, seven years after my first symptoms, but also the news that the intravenous antibiotics used to blitz the bacteria in my body had been like a chemical hurricane to the delicate vestibular system of my inner ears.

‘This can grow back in birds,’ Dr Welgampola told me, ‘but not in people. I’m afraid you’ll need to use some kind of walking aid forever now. And as for swimming, very dangerous because you’ll find you’ll violently tip over when you shut your eyes.’

I needed Jim to turn this excess of bad tidings into a joke. But he would’ve been long dead.

My second summer in Ant and Bee is so hot that I seek refuge in the mountain streams west of Canberra. When I soak my MS-troubled limbs in the dark cool water of Micalong Creek all vestiges of self-pity wash away. How can I possibly feel sorry for myself when I acknowledge that it’s adversity which brings me again and again to the most beautiful places?

As Welsh poet David Whyte has written, there’s a necessity for a frontier in your life, ‘for a cliff edge, for an internal outlaw, for a sense that you’re not completely in control, that you have edges of vulnerability and unknowing’. Rather than this making you weaker, he concludes, it means that you learn to pay tremendous attention, to go deeper still into the mysteries that compose a life.

For instance, ever since I set out in Ant and Bee, I began noticing hearts. Their shape is everywhere.

Sometimes a footpath in a country town where I stop for fuel and food can seem like artist Jim Dine has been present, slipping heart stones in when the concrete was still wet. Up in the dimpled shadows of sunlight in trees, green hearts growing daily. Hearts in bark and heart-shaped ant holes. Even leech bites seem to scab up in this shape, as if to tell me that love will heal all wounds.

I’m still camped on Micalong Creek the day someone’s four-wheel drive hits a wallaby. She dies later that afternoon under the shelter of blackberry bushes. Each day I check the rate of disintegration, I take the opportunity to do a bit of dying practice. I don’t want to be caught out again, so unprepared, so imprisoned in a hospital. All bitter grudges in me disappear when I contemplate even my worst, most hurtful old friend or lover dissolving into the ground in the way of this small wallaby.

Golden flies arrive first, pouring in and out of her mouth and eyes like living jewels, just as they would with any corpse. Only a matter of days before the spinal vertebrae stands bare, in a way that makes me finger my own backbone. Beetles then, doing their urgent work.

‘How come you didn’t go to hospital before you turned into an emergency?’ I’m sometimes asked as, less in need of solitude now, I begin to dip into the lovely lives of old and new friends. I think of my ex-partner’s certainty. My desperation. The feeling that, Job-like, my walking mystery had simply branched off into new zones of diabolical pain. The danger inherent in any hubris-filled philosophy.

Fragments of ancient Persian poetry catch the nature of my longing better than anything. I get down my good translation of Hafiz.

When the violin can forgive the past, it can start singing.

When the violin can stop worrying about the future, you’ll become such a drunk laughing nuisance that God will then lean down and start combing you into his hair.

When the violin can forgive every wound caused by others, the heart starts singing.

Sometimes forgiveness comes easily to me as I attend to the Ant and Bee bed. Ten minutes at least of unrolling mohair blankets, unstashing the sleeping-bags that unzip into doonas. Then to pack it up each morning? Probably ten minutes. It’s a moving meditation of which I never grow tired. All the folding, all the smoothing of cloth, all the exact stowing of possessions so essential for life to remain operational in a space the size of a walk-in wardrobe, somehow moves me ever closer to acceptance.

Also the ongoing baking of sourdough; for bread eases all grief, as Sancho Panza told his mule Dapple after a fall, proffering him some from his pannier.

On and off all morning as I set out these memories, the formica top of my bush desk has been holding the reflections of a pair of wedge-tailed eagles. Except for the sound of my carbon valve, all is peaceful. The sound is exactly that of Ant and Bee’s indicator. My heart is pushing blood into the chamber and the valve flicks open then shut, to stop any backflow.

If I make a coffee on my camp stove, the valve, in anticipation of caffeine, will pause or gallop. It’s as if Lord Cut-Glass from Under Milkwood, in his ticking kitchen, is scampering around inside me. Ping, strike, tick, chime and tock. It can be worse at night, this feeling that, Dylan Thomas–style, ‘I am tocking the earth away’.

I think of an archaeologist or a child of the far future picking up the remains of my heart valve. Where will it end up, this tiny mechanism, which Dr Grant says can last two thousand years? I imagine it rushing away in a river, or lying on a rock long after my flesh is no more. What about those ghost-story hearts, beating away after death, Edgar Allan Poe-style? If I’m cremated will it withstand the heat?

Tick, tick, tick, there’s no escaping my very own eggtimer.

The 100-watt solar panel that powers my laptop, fridge and printer resembles a book propped open to the sun, its huge pages waiting for my words. I have it angled to face north-east, diagonally left of the bonnet. The solid iron curves of Ant and Bee offer more than protection from the sun and breeze. Often spiders set out webs under the driver’s side mirror, so that putting down my pen the better to watch, I understand how immensity exists in fragility.

The day a red-bellied black snake appears summer is turning into autumn. I’m typing fast, hoping to finish before dark. The snake’s behind me, quite far off, about to slide into the undergrowth. However moments later, as I glance sideways to check, its tail is right next to my chair. It’s an old snake and as I ease my gaze down between my legs there is its head, right between my feet, moving in such a way that it appears to be dancing to the rhythm of my valve.

I have been doing another kind of writing, too, on a quilt that’s growing as I travel. In my camping life I use so many calico oat bags that they’re a natural choice for the panels of the quilt. With the distribution of bags to new participants comes the feeling that I’m handing out thick blank sheets of paper. One side of the quilt retains the stencil of the grain company, preserving the caring wisdom of the organic cereal world. The other holds people’s interpretations of wisdom.

The Djuna Barnes quote from my long-ago invalid scooter is the first to appear. I sew sorrow marks too: recognition that other calico bags once held flour laced with poison to wipe out the forbears of the Aboriginal countries I’m travelling through. Bundjalung, Gumbayngirri, Gurringai, Darkinjung. I put down in the slow handwriting of sewing the names of the nations so devastated. Yuin, Wiradjuri, Ngunwaal, Walgalu.

‘That’s Wunyella,’ a woman says when I tell about the snake under my desk. ‘From up the north-west channel country. That red-belly snake. She represent Aboriginal womanhood. Healing. What about someone do Monkeemi, the little grey wind of dawn? If you want I could sew that one?’

To somehow convey the desolation I feel whenever there’s no way in to country where I might camp, one panel might just have to be angry. Fence after fence after fence. Sign after sign. The country carved up in ways that hem in my eyes. ‘Trespassers will be shot.’ ‘Private.

Do not come in.’ And, most memorably, ‘Fuck off U Tourist Cunts.’ That so much land looks as if it’s undergone five generations of chemotherapy in order to turn it into paddocks can also bring the sharpest grief.

But on other days I have to down pen or needle for a wild dance, my walking-stick flying off my arm. That yelp of delight under the forest oaks? That yip of animal-like pleasure in a forest of spotted gums near Tanja? That’s me. That’s my ever-increasing recognition that, instead of being dead and buried, or stranded in Brickland these past two years, I’m streaming with life.

If I sometimes take off every item of jewelry and every piece of clothing in the dark, under stars, it’s only in order to be as close as possible to that which I don’t understand. Lying alone in front of my campfire with my hands over my heart, what is this great love I can feel drifting into me, as if the sky has come inside? Why is the dark rocking me like a cradle?

Ruach. I remember a priest in hospital explaining the old Hebrew word to me. The power at the base of breath and wind – the invisible, always feminine force. As he spoke, I could feel a channel of fresh air brush my face; only narrow, as much as could flow through the two-inch gap of open window, all that was permitted since the day a patient had leapt from it. But ruach nevertheless.

On such camping nights I’m more peaceful than I’ve ever been. But only if I keep my hands over my heart. As if this lover, though mysterious and unseen, still needs skin to exist.

More than ever I’m hard pressed to describe the nature of my faith. Such a tingle of doubt and desire. If it often seems lost altogether, I remind myself of how frequently more ordinary items disappear inside my van: within moments sometimes, sheets of paper or a favourite pen vanish. Only once I stop fuming does the item miraculously reappear. Perhaps this idea also belongs on the quilt – that something lost will only be found once you stop looking.

Only a few of Ud-din Attar’s birds made it safely through the seven treacherous valleys. Their ordeals were not in vain, for as they finally faced the majestic Simorgh, their king, they beheld a vast mirror of shining planets, endlessly reflecting each bird’s unique being. With the realisation that each of them had always contained God, the birds dissolved through the mirror into blissful eternity.

For some reason, though it may only be a problem with the translation, the ending seems too self-satisfied to be convincing. Too smug. No wonder it’s taken me so long to finish.

No, I think, remembering the bull ant that has spent the day building a circle round my campfire cushion using light-coloured bark but dark twigs. Give me insects over answers any day. Give me wattle pig weevils with kind eyes. Or dragonflies agleam with dew. Give me the tenacity of the ugly small forest lizard I saw burying her eggs one dusk. Even after I’d roared around and around and reversed and heaved Ant and Bee into the best position facing north-east, she must’ve kept up her digging. Scufffer-scoof. Scuffer-scoof, scoof-scoof-scoof. The sound of her claws as, sitting between the open back doors, I sipped my tea and watched.

Give me sunny days and give me rain. Give me the happy song of my tiny kettle whistling on the gas burner by my pillow. And if this is prayer I realise I really love it, especially if what comes is the exact opposite of what I think it is I need.

As I enter my third year of living this way, I’m increasingly aware that these are days that will never come back. Even with an LPG tank next to the petrol one, the soaring price of oil means that I can’t keep driving around in something powered by a V8 engine.

I think I’m addicted to diversity. I love my laundry/hot-shower days in caravan parks I’ll never revisit. Oh, the easy pleasure of finding that an old caravan park just two hours from the Victorian border has a new bath and ample hot water. How satisfying is the easy comradeship of a chat in front of the water tap as I fill my containers. Freedom from rates and electricity bills? Not cleaning my bathroom or wheeling out rubbish bins? These are the sorts of prosaic facts that also gild my days.

‘I used to have one of what you’re sensible enough to be using,’ the dispirited owner of a Winnebago Motorhome, broken down for the fifth time in as many months, tells me. ‘Probably mine was a bit older. A ’63 with green trim, she was. Reliable. Not like this friggin monster.’ His second chin swings in the direction of the Winnebago. ‘So don’t you ever let go of your old girl.’

But of course everything shifts, everything must come to its end. In my darkest hospital days I used to imagine the destruction of even the hospital. Cranes with dinosaur jaws and chains bringing it down. To contemplate Ant and Bee at some wrecker’s boneyard of the future makes me want to cry. This old ambulance, which has become my ambulatory vehicle – disabled housing like no other – is so integral to my own, ever-altering curve of joy.

Instead of crying, though, I push open the back doors. The huge frame they form around the scenery beyond might well have ruined my enjoyment of anything confined in a gallery forever.

Physically I know I’m much stronger. With my walking-stick hanging on my shoulder just in case, I can walk ten times further than I could in my Brickland days – a whole mile or more of happiness. It’s been over a year since I’ve had to use my fold-up walking frame on wheels. Whereas once upon a time I could barely scramble the step up into the cab, now it’s an effortless glide. I’ve developed the agility of a child, equally at ease cross-legged as out on my belly with my chin in my hands. I swim in rivers. I can catch waves. I love how this way of life takes me outside into exhilarating weather that a house encourages you to avoid.

I think I’ll keep driving south tomorrow. No matter if it rains. No matter if all the meaning I’ve attached today to my strange life drifts away with the light of sunrise. The God of Lost Things in Ant and Bee will surely come again to my rescue.

Meanwhile my days ahead are going to be clear. Which you, why? And full of the little birds that sing in questions.