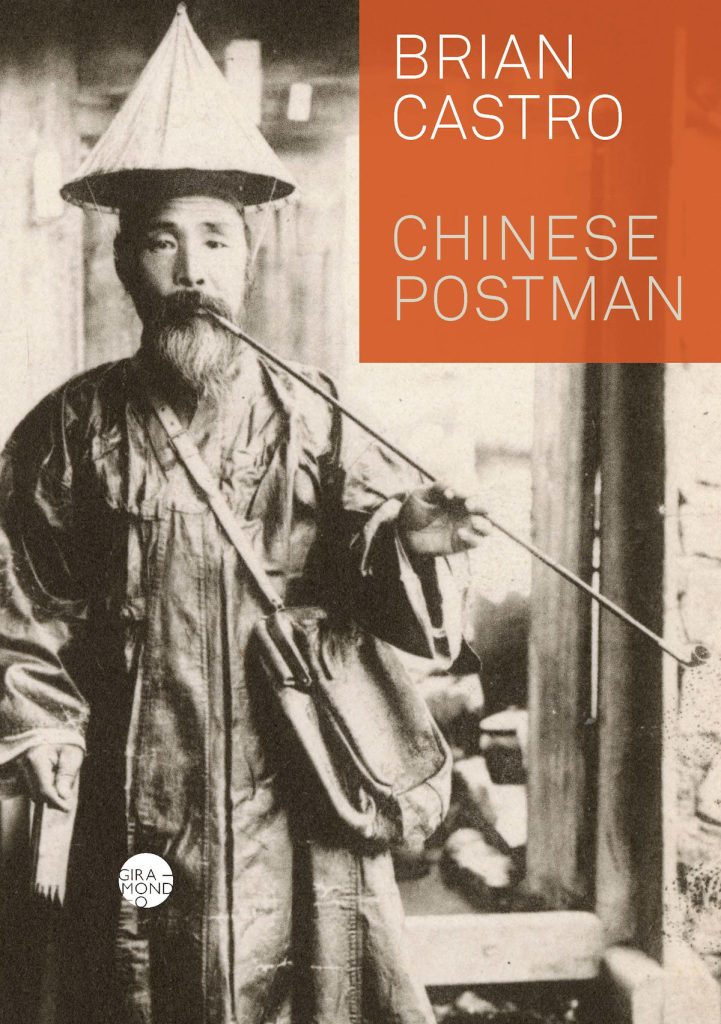

An excerpt from Brian Castro’s Chinese Postman

The following excerpt is from the opening pages of Chinese Postman by Brian Castro (1 October 2024), one of Australia’s most important novelists. It centres on the character of Abraham Quin – a thrice-divorced man in his mid-seventies, a migrant, a one-time postman and professor, and a writer, now living alone in the Adelaide Hills.

How time-honoured custom reverts to ruin!

On summer evenings, during the vesper hours, after dinner, people used to take their walks in the parks, the gardens, and on the road leading up to the magic mountain. To see, to be seen, to make conversation, to connect with neighbours, shopkeepers and colleagues. There was always a low buzz of quiet exchanges. There was always soft laughter and sidewalk wine in front of the local art gallery.

No longer. Because the walk has become too muddy and slippery after the rains. And because of that solitary figure, that old man there, their passeggiata had all but been ruined. That’s me there. I have a bad back, few teeth and I’ve lost my smile. And these are the Adelaide Hills.

That lone walker, yes, that stooping figure over there, that bitter and twisted man who only straightens up to look at treetops and sees nothing but fragments – ruins are his best friends. He sees only broken columns lying horizontally in the grass, symbols of fallen ambition. He does not know many people now, or only by sight. Most of those his age have passed away. The killing zone, he calls it. It occurs within a few short years. He is too old to connect with young energy; with their rapid rattle of rap; their pointers of no universal significance. Too tired to talk. Most of those he knew well are now in their graves. A heavy burden. Walking slowly is the most he can manage. Count the steps towards oblivion. And because he is loath to talk, others also stay silent as they pass. They sense something funereal that they should not engage with, something that may infect them. Like his cigar smoke, which they treat like asbestos dust. Environment; environment. They should all wear masks, he thinks. But they are all destined to die. Gradually, those who pass do not resume much conversation within themselves afterwards, since the hand of solitude and pessimism presses down upon them more firmly. They sense it, but it’s not for articulating. It’s a disturbance of wellbeing; a virus or a miasma: on the main street, over the town, the parks, the esplanade. Children stop screaming. Dogs stop barking. Choirs stop singing. The caravans have long gone.

He talks mainly to himself. Clears his throat often. This guarantees others will stay away from him: To speak truth to power is a case of putting the cart before the horse. One must speak powerfully to ‘truth’, that is, rhetorical power to expose the deafening truth; the truth which is usually bare and dull. Bring on the catastrophe with the illusion. Oral art before going hoarse. The thing is, how not to lose effective words, both in terms of brain cells and through rigorous rote and painstaking transcription? Every process is lethal since words can fall through seams of syntax and can turn out to be their opposite when the process is completed. But that is all youth and myth. In time there will be detachment, and then disgust and then silence. Words fail faster than music. I dislike the political feebleness of poetry and hawk with contempt for those who try. But I honour those who have been tortured or imprisoned.

I snort a lot. I spit. It saves on handkerchiefs. Better for the sinuses anyway.

He hates these italics inside the mind. People, especially writers, cannot read them, or they nod off. Less literary readers of ebooks confuse these declamations and emphases with popular highlights. Nobody takes note of anything. But writers are the worst in exhibiting their narcissism. There are too many writers with too much preciosity, who even after their deaths do not leave an impression of having been very memorable. They may have written fairly well, but since they were totally self-involved, they had no textual camaraderie, they leave behind a residue of grey skies rather than warm light, the former redeemed by distant lightning and faux self-humbling. No humour. No revolution. I forgive them for dying, but not for the afterburners smelling of ozone that gave them stardom. They should speak to you still, like Shakespeare, with diabolic emancipation, piercing reason, paranoid fantasy or drunken spit. One should still hear their laughter in the dark. But perhaps it is better for the observer to be acerbic and smile at how literary memory grows out of waste, of schadenfreude and shit. Shit is the highest form of subjectivity, more meaningful in defining the individual than the sublime. It is both dialogue and meditation. Medieval monks have now been found to have had massive intestinal worms. Wrigglies coming out of their backsides in their sleep. All because they fertilised their veges with human waste. Meditation was recycling, like night soil. Why ‘night’? The stink was constant, twenty-four hours a day. Flies. Floating words like clouds forming and reforming: different each time and unpredictably so in terms of the winds of honesty. It is important to collect honesties upon dying, important to know its odours. Know thy worms. Consume thy worms. Worms make rich soil. Monks slept very little. They produced illuminated books; books of hours; which turned into short stories; legends; tales of chivalry. Worming their way into popular culture.

Writing makes matter out of metaphysics. To do it the other way round is an insult to life. Abe Quin…for that is my name. I am a scrivener. Not Abe Quill, though that would sound better. Abe Quin makes kirigami flowers out of newspaper. He loves to see them blossom when cast into the waters of the lake. Children are delighted by it. Capillary action is the scientific explanation; but what he makes is not above physics. It is not a metaphysics. Aphorisms should have the same effect of blooming, he thinks, without metaphysics or explanations.

They simply expand through leaping frogs of metaphors, which are physical, morphing in the liminal. For delight, just add water. Water finds its own level, as any plumber will tell you. It discovers and corrects and steadies the world. But these flowers have no smell. It is important that writing smells because life smells. Dogs are alive because they smell.

From pages 1-4