Transcript: Marion May Campbell’s launch speech for Chinese Fish

Chinese Fish by Grace Yee (June 2023) was launched at The Alderman in Brunswick East at a sold-out evening event. The launch included readings by Yee, as well as from fellow ex-Aotearoa poets Alison Wong, Saradha Koirala, Xiaole Zhan, romesh dissanayake, and Manisha Anjali. Poet, novelist and academic Marion May Campbell wrote the launch speech, which was delivered by Lisa Gorton on the night. Read a transcript of Campbell’s speech below.

Chinese Fish is a brilliantly devised, comic feat of cultural resistance; a fantastically polyphonic verse novel majoring in riotously funny and heartbreaking ways, the minoritised experience of three generations of a Chinese family, who in the 1960s migrate from Hong Kong to Aotearoa / New Zealand, or, as white Australians hypocritically used to joke, the land of the wrong white crowd.

Its most intense emotional charge comes from the struggles, triumphs and resistance of the female characters. There’s the doubly silenced Ping, crushed and exploited both by internalised patriarchal oppression, emotional neglect by husband Stan, and the pervasive racism, both blatant and casual from the host country, and there’s her feisty Hong Kong-born, first child, Cherry, whose coming-of-age story the work also intermittently charters. But Stan and Ping’s other children, Joseph, Lenore and Starlit, a host of minor characters, co-inhabiting in-laws, neighbouring kid bullies and friends, also emerge vividly alive through the narrative fragments.

The economy, dramatic verve and imaging give these fragmentary story-worlds an almost hallucinatory intensity. Uncompromisingly, Grace builds this tessellation of poetic and dramatic fragments into an ever-more resonant mosaic, allowing the reader to circulate in freely imaginative participation in the gaps. The work is all the more brilliant for eschewing the conventional lyric and also for being free of polemic and interpretative commentary. The voicework performs the scenes for us throughout, setting into friction the dynamic exchanges between family members, in their Cantonese-inflected English, (with interruptive Chinese characters), plunging us directly into each newly unfolding stage of their material and white-bread, milk-tea cultural accommodation to suburban middleclass life, with the virulently racist Sinophobic journalistic diatribes, slogans and casual slurs, playing in their grey font like a gruesome drizzle through the text.

It’s an ingenious mode of poetics driving the work (in all its experimental graphic, spatial, and narrative dimensions) and it’s all the more remarkable, that despite the jamming of speech acts from a huge range of genres, with their culturally saturated images, ads chanting the seductions of new domestic appliances, or the visceral intersplicing of body events in pain, danger and pleasure, the multiple stories emerge with a secure dramatic contour.

Through the voicework, Grace unfolds the often ingenious and sometimes desperate ploys of the family’s adaptation to a frequently hostile culture, with passing and subterfuge working as oblique resistance. Grace’s satirical brio, her delightful riffs on the absurdities of masculine behaviour, for instance, her deflating laughter before injunctions to aspire to conventional feminine beauty, and her complete eschewal of sentimentality before even acute suffering – all sustain the reader’s empathetic connection as they participate in the community.

The painfully edged comedy of daily survival is pervasive, though. A major motif that runs through the verse novel’s seven sections is the rat-plagued fish and chip shop, which is the economic engine driving the family’s quest to thrive:

Or we could look at the way the cinematic montage swoops us to the centre of sacrifice and pain: after a wonderfully abbreviated sequence of who is doing what in the household, we find Ping (whom we know from Grace’s vivid and succinct evocations to be clever and beautiful), throttled into illness by endless hours of enslavement over the fish, chip, and sausage vats, on top of all the domestic labour with the big extended family, venting her sorrow regarding her faithless husband. (p.50) And later (p. 87), her rage emerges: you dead man you dead man you dead man.

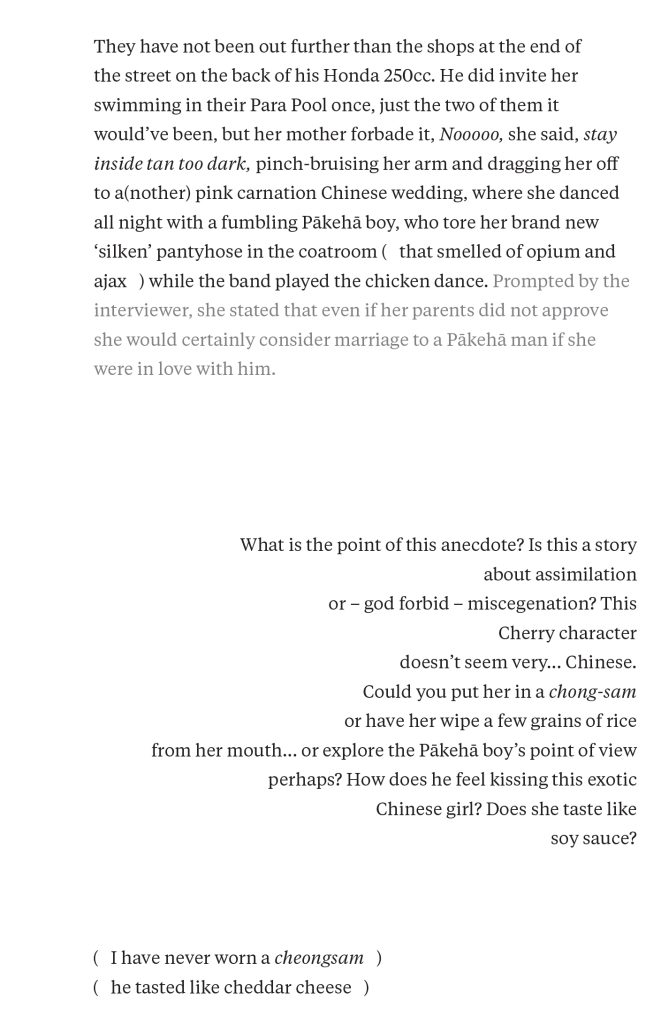

But this rage is countered by the delightful evocation of Cherry’s coming-of-age, her experimentation with Punk gothic rebellion with her superb friend Delia, and her sampling of Pākehā boys’ attractions.

How about Grace’s parodic verve here, poking her tongue at the persistent orientalism corroding the ‘politically correct’ veneer. Here’s nothing like laughter to undermine the power of the would-be assimilationists and to disarm virtue-signalling Anglo-Celt post-colonialist critics.

It’s impossible in a few minutes to account for the extraordinary richness of this masterwork with its myriad story-worlds, bestowing us a host of gorgeously flawed and entirely engaging characters.

Chinese Fish is a great artistic triumph that I do hope you can fully celebrate tonight, and that deserves all the critical accolades it will surely attract.

Congratulations Grace!