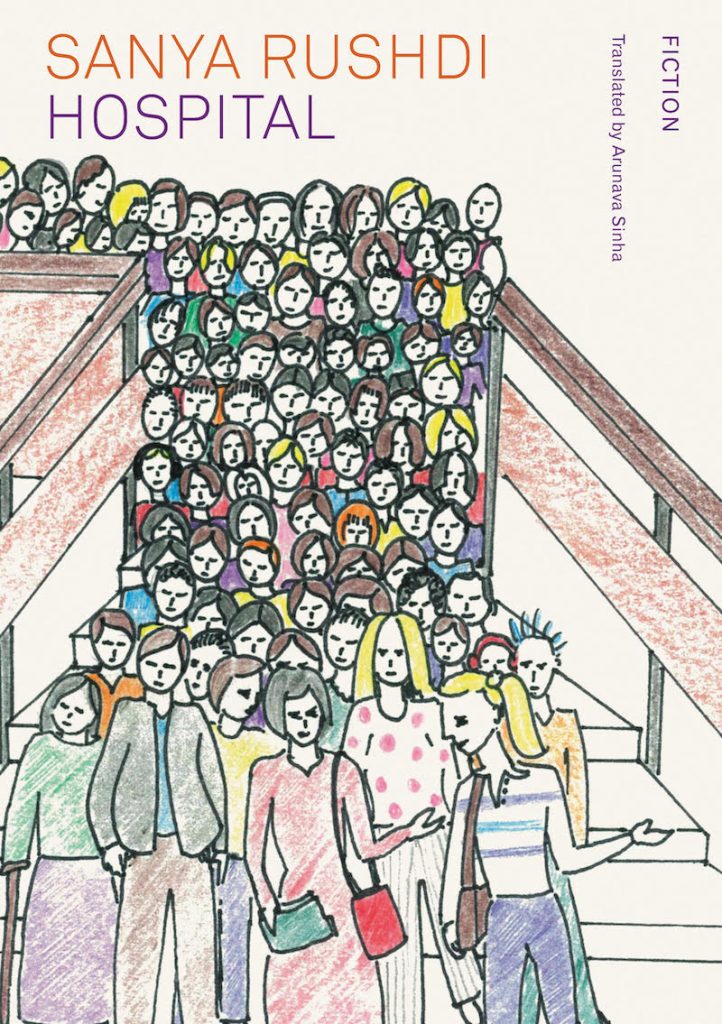

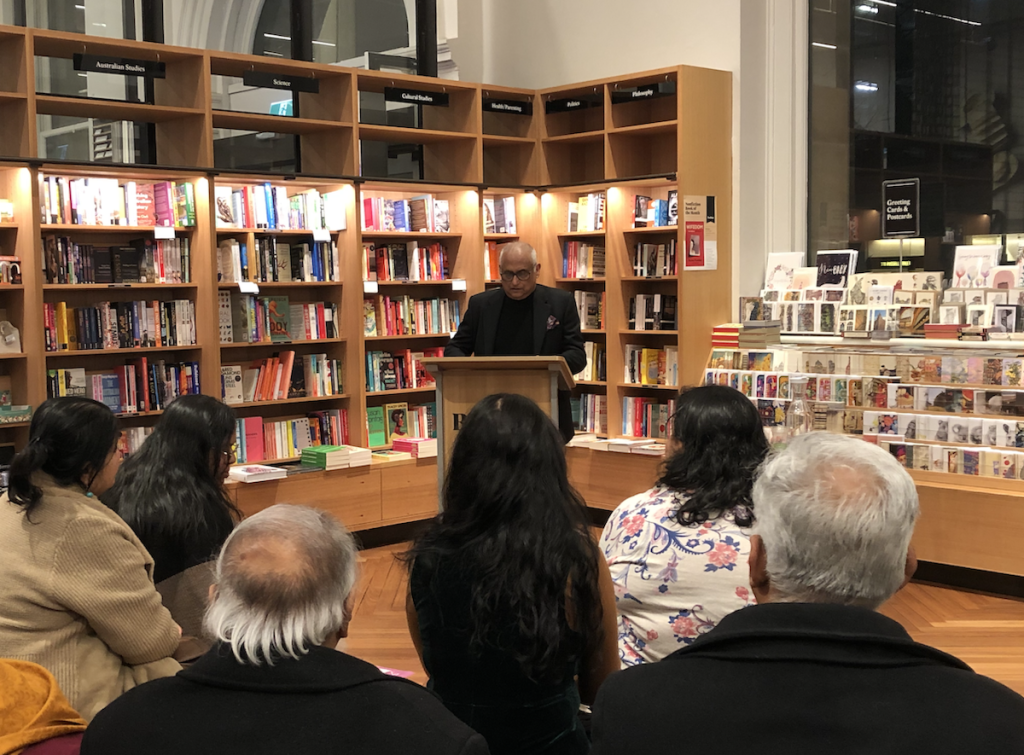

Transcript: Adib Khan launches Hospital by Sanya Rushdi

The acclaimed novelist Adib Khan launched Sanya Rushdi’s debut novel Hospital in July 2023. A transcript of his speech is published here.

What reality often hides or obscures, literary fiction frequently reveals as the unacceptable truth. The best in serious fiction jolts us into a realisation that there is a glaring discrepancy between the perception of living in a free society and the punitive reality of restrictions and rules which must be obeyed for a community to function within its social and political structures and without too much disruption. The truth is that an artist often has to contend with a flawed and gashed humanity. And this is what we confront in Sanya Rushdi’s novel, Hospital. As readers of this novel, we have to brace ourselves and engage emotionally and intellectually with words and ideas which are sharp and prickly. They are more than likely to offend our sensibilities, shake our values and challenge those conventions around which we build our lives. A meaningful novel compels us to feel and think. It can make us uncomfortable. There are those who believe in the virtues of a ‘feel good novel’ as the definitive measurement of quality literature. I don’t happen to be among them. I want to be prodded and to be made uncomfortable by what I read. Perhaps it is a form of cerebral masochism. The ultimate stimulant of the reading experience is a series of questions which crop up as the narrative unfolds but for which there are no reassuring answers. This is what happens when you read Rushdi’s novel. Acceptance does not mean resignation. That is one of the fundamental issues explored in Hospital. There is not always a single way to treat those with mental health issues. A civilised society is also compassionate and broad-minded and it is a moral imperative to approach those people who need help in the way that is best for them, offering understanding and inclusion, listening to their concerns and the ways in which they want to be treated. Unfortunately, this is not always the case.

One of the striking features of Hospital is the clarity and succinctness of the narrative. Often Rushdi uses short sentences without too many embellishments of figurative language. The language is bone dry. There are no distractions or deviations, no flourishes and no extravagant metaphors or similes. The stark simplicity of expression enables us to freely explore her inner world of turmoil and her perception of a threatening world out to get her. We learn of her fear of ‘pigeons, dogs, cats, moths, cockroaches – anything that moves.’ She is afraid of anything coloured brown. Most computers, by her reckoning, are for the purposes of monitoring and control.’ She is fearful of mobile phones and the harmful effects of radiation. She doesn’t feel safe in institutionalised living and constantly expects a mishap at ‘any moment, a robbery or murder or kidnapping.’ This paranoia underlines her insecurity which is at the core of her problems. We are not only privy to Rushdi’s inner world but also the hierarchy of the community house where we see well-intentioned professionals, seemingly dedicated to the welfare of the patients but narrow and insular in their belief of what constitutes effective treatment.

There are parallel worlds fictionalised in Rushdi’s novel. We read about those human fallibilities which plague society at large. But somehow, they take on a more sinister dimension when they are presented within the confines of a limited community life. It is hardly surprising that bigotry and racism are manifested in the common activities of everyday living, even among those who are frail and need help. There are moments of brutal insensitivity in every day living as in the scene where the protagonist refuses to eat chicken parmigiana because there are bits of ham in it. Some at the table find this adherence to her Islamic belief funny and burst into laughter. But Rushdi’s emphasis is on mental issues themselves. It is not easy to confront and acknowledge the anguish of a mentally ill person. Consistent throughout the writing is Rushdi’s resistance to the controlling forces of a system which treats her with its myopic dependence on medication. Hers is a struggle for the retention of an independent mind and the right to question the treatment she receives. The defects of a social system which supposedly represents the best and most advanced in medical science are exposed in her conversations with the experts who attempt to help her. What the medical practitioners do not understand is that despite Rushdi’s problems she is quintessentially an ordinary human being with ordinary human needs. She has needs common to everyone in a community. She has sexual desires, she longs for love and compassion and emphasises the importance of communication. Medical treatment is the least of her priorities. ‘All I need,’ she says, ‘is proper help, based on conversation, not medication.’

The sustained tension in the novel is primarily the result of the first-person narrative which takes us close not only into Rushdi’s inner world but also into a community house where we come across professional medicos seemingly dedicated to the welfare of mentally ill patients. There is an ongoing struggle between those who seek to cure and those who are subjected to the treatment which modern medicine offers. One of the main aims of the treatment is to stabilise and promote self-control. Dr Wong directly addresses what he perceives to be Rushdi’s problem. ‘Your mood isn’t stable,’ the doctor tells her, ‘you have no control over yourself.’ Rushdi sees the attempt to manage her as an extreme form of repression. ‘The self,’ she says, ‘is subdued with medication at every opportunity.’ In Ken Kesey’s groundbreaking 1962 novel, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, one of the mental patients, Dale Harding, observes, ‘In this country, when something is out of order, then the quickest way to get it fixed is the best way.’ And this attitude is prevalent in Hospital. Rushdi’s novel is not only an exposure of the inhumane way that mentally ill people are frequently treated but also a plea for help. Her cry is for someone who ‘is in possession of both common sense and compassion.’ And that compassion is a healer. It is ‘based on conversation, not medication.’ Rushdi argues that there is not always one way to treat those with mental health issues. We, as a society, must do our utmost to approach and treat people in the way that is best for them. We must offer understanding and inclusion. The institutionalisation of those who are mentally ill and the reliance on modern medicine as quick-fix curatives are crucial concerns in Hospital. They represent the oppressive mechanisation, dehumanisation and emasculation of those who do not fit the perceived norms of society. One of the residents pleads his case to Russell, the bodybuilder: ‘I am a human being and you have to treat me accordingly.’ It is the supreme irony of the novel that in a free society there should be institutions which exercise such cruel control of individuals even as they try to liberate and cure people shackled by their mental conditions.

The novel opens and closes with a focus on art. The media res opening of Hospital lulls us momentarily into a state of calmness as we are invited to examine some of the details of Claude Monet’s painting, Bridge Over a Pond of Water Lilies. We wonder why the narrator suddenly decides to sketch what Monet has painted. In itself Monet’s picture not only captures the calm beauty of nature but also sends a powerful message about finding a balance between human existence and our environment. But very quickly, the sketch moves in a different direction because within herself Rushdi does not find any compatibility between her inner chaos and nature’s calm beauty which characterises Monet’s painting. There is a pond within which is an island connected to the mainland with a bridge. Its last step leads us to a lotus. Much later in the book, as she sits by a window and observes the changing weather pattern, Rushdi discloses that ‘There have been storms outside throughout, the state of my mind matching the state of nature to provide some sort of consolation.’

By the end of the novel we return to Rushdi’s picture which she sketched three years previously. If ever, Samuel Coleridge’s famous line about the Willing suspension of disbelief was applicable to a reader, then it comes into effect in the last page of the novel.

There is calmness in the scene which Rushdi describes at the end of the novel. But there is also a sad realisation of the inevitability of another attack of psychosis at some future point. That does not dampen the hope of healing by not using conventional medical therapy. The sketch based on Monet’s painting is eventually fashioned after Rushdi’s own needs. There is gentleness, love, harmony and communication. There is something mystical and elusive but ultimately fulfilling about the book’s ending. We return to the island connected to the mainland by a footbridge where trees grow and flowers bloom. Among the intertwining trees, there is one that stands apart. The lotus is still there except now people talk to it. Man and nature appear to synchronise as an alternative process of recovery and living together. There is unfettered growth which complements the mind’s endless search for the self. The solitary tree continues to grow until its top almost touches the clouds ‘where the birds fly.’ It brings to mind what Henry Beecher, an American clergyman, said: ‘Every artist dips his brush in his own soul, and paints his own nature into his pictures.’ Above everything else, Hospital teaches us about the irrepressible condition and the resilience of the human spirit and what it means to be human. Hospital is a very fine novel which gives us much to think about. I urge you to read it. It is with great pleasure that I launch Sanya Rushdi’s debut novel. Thank you.

— Adib Khan