Suneeta Peres da Costa: a note on The Prodigal

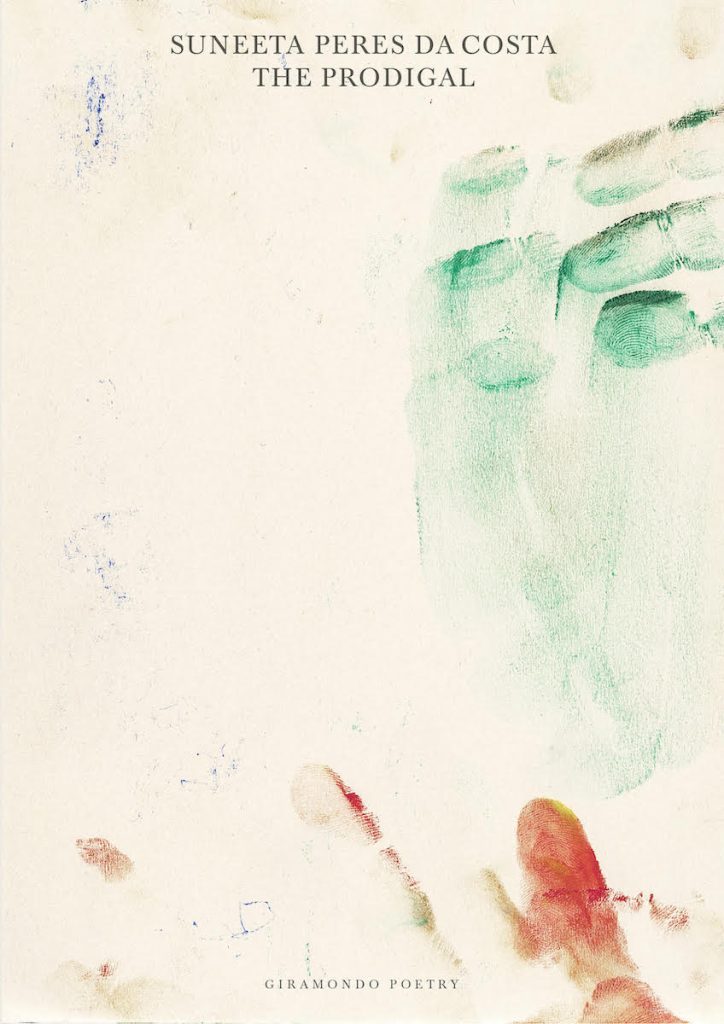

Suneeta Peres da Costa reflects on her debut poetry collection The Prodigal (1 November 2024). Her first book since Saudade, shortlisted for the Prime Minister’s Literary Award for Fiction, The Prodigal unravels myths of homecoming and return, belonging and displacement, patrimony and sovereignty.

Travelling in a North Indian city some years ago, I got lost on the subterranean floors of a public building and even more disoriented by a sign I saw on a doctor’s door: ‘Sex determination of foetus not performed here’. Wanting a child myself at the time, it was what the sign didn’t say which provided the entry point, or portal, into the title poem’s psychological world.

When I knew Giramondo wouldn’t go with ‘and Other Poems’, the ‘The Prodigal’ felt sufficiently expansive to encapsulate the myriad meanings and associations of the whole manuscript. I observe that these deviate from, even escape, canonical ones of the parable of Luke 15:11-32 – familiar to me from a Catholic childhood – with its settled arcs and redemptive imaginary of home and patrimony; leave-taking and remaining; the lure and māyā of foreign travel; filial piety and disobedience; servants, masters and indentured labour; want and abundance; squandering one’s inheritance; self-realisation, repentance and humility; forgiveness and reconciliation.

The Prodigal is itself a patchwork of poems, sewn together from different modes –lyrical, narrative, confessional, dramatic, prose. To the extent that their identities can be called diasporic, the poems’ speakers register a contested sense of belonging to history and country, through a reckoning with imperialism’s traces and encounters with contemporary forces of ecocide, ethno-nationalism, gender and caste violence.

The word sūtra – in Sanskrit meaning a string or thread, or even collection of threads; that which holds things together; aphoristic syllables and words woven together; a condensed verse or text – arises a few times. Spiritually, a sūtra may also of course be a prayer or invocation; for instance, the Heart Sūtra. Sūtra are also written on prayer flags whose threadbare fragments birds carry away to make springtime nests (this is occurring just beyond my window as I draft this Note).

The poems, invoking gods and goddesses, stigmata and samskāra, simultaneously conjure the mystical and the mundane world: skins, scars and tattoos; frogspawn and spiderwebs; sand-lines, battlelines and fissures; wombs, soil, hair and vines; blood and leads; scissors and axes; banksia and thorns; husks, shells, songs and bells. Metaphors of suturing, mending and healing act as counterpoints to cutting, breaking and tearing, I hope testifying to the inextricable connections between the landscapes of the body, the living Earth and interbeing.

— Suneeta Peres da Costa, October 2024