Lisa Gorton: a note on Mirabilia

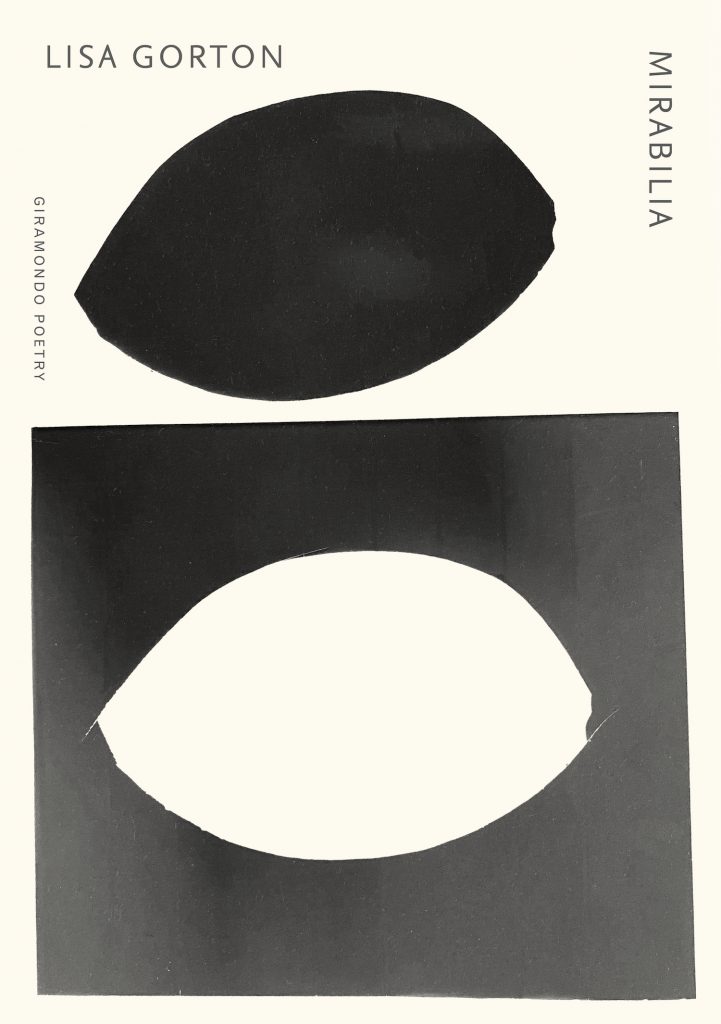

Lisa Gorton reflects on her poetry collection Mirabilia (August 2022), which follows on from her acclaimed books Hotel Hyperion, Empirical and The Life of Houses.

I wrote the title poem Mirabilia during one of Melbourne’s lockdowns. It’s a poem about pangolins: the most-trafficked mammals on earth; they die in captivity. Perhaps, scientists said, the bat coronavirus mutated in a human host; perhaps the bat and pangolin coronaviruses met in the same host, caged together.

‘Mirabilia’ is also a meditation on a line in Marianne Moore’s poem ‘The Pangolin’: ‘if that which is at all were not forever’. ‘Mirabilia’ is written in Fibonacci syllabics, reflecting how a pangolin spirals up in itself. That pattern in the poem is also a lament for the natural pattern of growth and return, which has lived in the background of poetry’s images for so long.

Over time, reading about poets’ lives, I noticed how often mothers, particularly of male poets, are characterised as destructive. Slowly I started to put together a long poem ‘On the Characterisation of Male Poets’ Mothers’. For this, I set myself a rule: only to use quotes from Wikipedia, because, in this poem, I’m trying to hold to light to generally received ideas.

I wanted to disrupt the language of connoisseurship, organised around the dream of the male ‘genius’ – to force the experience of the artist’s muse back into the picture. I set quotes from Cellini’s Autobiography against the Louvre’s suave description of his artwork. And, after reading Bernard Berenson’s dismissal of Leonardo da Vinci’s painting The Benois Madonna – dismissed because the ‘young woman’ in it had ‘puffed cheeks, a toothless smile, blear eyes’ – I spent a year trying to trace the life of the woman who is, I think, the model for this picture.

So, the sequence ‘Tongue’ sets Leonardo’s artwork in context, in the year of the Pazzi conspiracy, when Giuliano de’ Medici was murdered, and it traces the life of Fioretta del Cittadino who was the mother of Giuliano’s child. After his murder, her child was taken and she was forgotten. Art, broken bodies, grief, effigies, and the myth of Medusa: these poems worry at the relationship between the human body and its language.

I wrote ‘Great World Atlas’ for Izabela Pluta’s artist’s book Figures of slippage and oscillation (Perimeter Editions, 2019). For this, Pluta made darkroom contact prints from three editions of the Reader’s Digest Great World Atlas. Her artworks have the colours of an x-ray. They show maps, overwritten, backwards against each other.

These poems track the vast extent of nuclear testing in the years of these editions. They include the careless brutality of Ernest Titterton, for instance, who, knowing that Britain had ploughed plutonium into the sands of Maralinga, said: ‘If aboriginal [sic] people objected to the tests they would vote the government out’ – when Australia’s First Nations people were unenfranchised, still.

In Mirabilia, I was questioning the relationship between art and politics. These poems are crowded with quotes, events, anecdotes, inventories, and fragments of myth, because I was trying to bring into poetry that heteroglossia (raznorechie, ‘varied-speechedness’) which Mikhail Bakhtin found only in the novel: a clash of different voices, different conceptions of world.

— Lisa Gorton