On ‘Alive in Ant and Bee’ by Gillian Mears

I’ve arrived late to Gillian Mears. Or exactly when I ought to have: standing in the morning rain at Adelaide Writers Week for a panel on biography, two days after a car wreck, not yet able to fully open my jaw. Towards the discussion’s end, Bernadette Brennan, Mears’s biographer, urged the audience to seek out ‘Alive in Ant and Bee’: ‘the most extraordinary nine and a half thousand words you will read’.

Two nights earlier, driving to Adelaide from coastal Victoria, I’d rolled my station wagon off the Old Coorong Road. I’d left the totalled wagon at a wreckers’ yard, and most of its contents – camping gear, tools, fold-out aluminium table that had lately served as writing desk – with an octogenarian cattle musterer back in Kingston S.E. I had no idea what the Mears essay was about but I was in the receptive state particular to near-death experiences: renewed meaning lurking at the perimeters of every other encounter. Or maybe it was the effects of lingering concussion. Either way, I was happy to be told where to look.

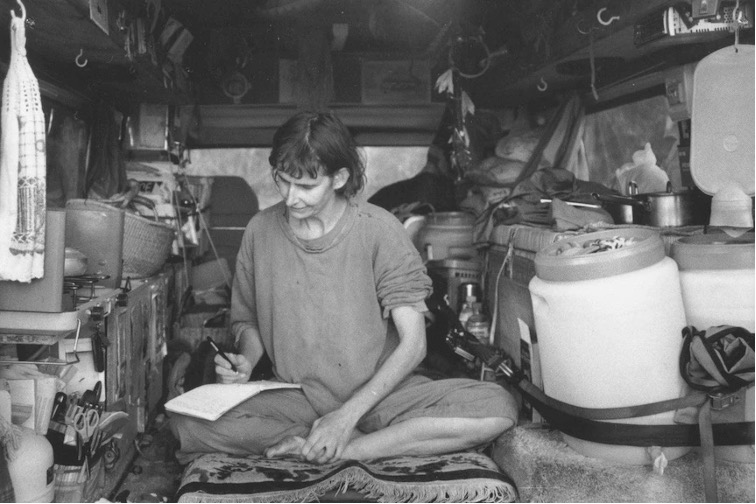

From the outset, ‘Ant and Bee’ – the yellow F100 ambulance which is to become Mears’s home, studio, escape vehicle, muse – is imbued with the animism that she affords all things. ‘Calyptorhynchus funereus,’ she notes of the duco, ‘the black-tailed cockatoos that always scream upriver when people I love die.’ The absurd gamble of the ambulance, of paring one’s life down to the dimensions of ‘a space no bigger than a bathroom’ in order to live out of said ambulance, seems less so once we are brought to appreciate the chain of cataclysms that have led to it: endocarditis, near-death by macrobiotic magical thinking, undergoing open-heart surgery alongside the debilitating progression of MS symptoms.

Within the logic of the essay – which is the logic of a life, shaped by extremes – going on the road in ‘Ant and Bee’ seems a sound avenue towards autonomy, becoming, as Mears puts it, ‘the solo driver of my own life’.

How to resist the metaphor of life in an ambulance, post emergency? Mears doesn’t: ‘last time I crossed the Clarence River in an ambulance, the siren was screaming and I was almost dead.’ A larger question: How to write about the tectonic upheavals of one’s life without listing into self-mythology? How to do so of a life that so readily deals out the stuff of myth? The figure – the driver, the writer, the woman – who emerges from these nine and a half thousand (yes, extraordinary) words is a firebrand, and in her telling there is both plenty of skin, and true mastery: ‘six shepherd hitch twists in the wire that put my sternum back together’, she writes. How the cadence here so perfectly conjures the repeated action, the sequence of deft, impassive rotations of a wrist.

‘The unendurable is the beginning of the curve of joy’, Mears quotes from Djuna Barnes, and in the pages ahead shows how one might live and love and work in fierce testament to this paradox.