On ‘Sticky Bread Gets Sliced’ by Jackson Mac Low

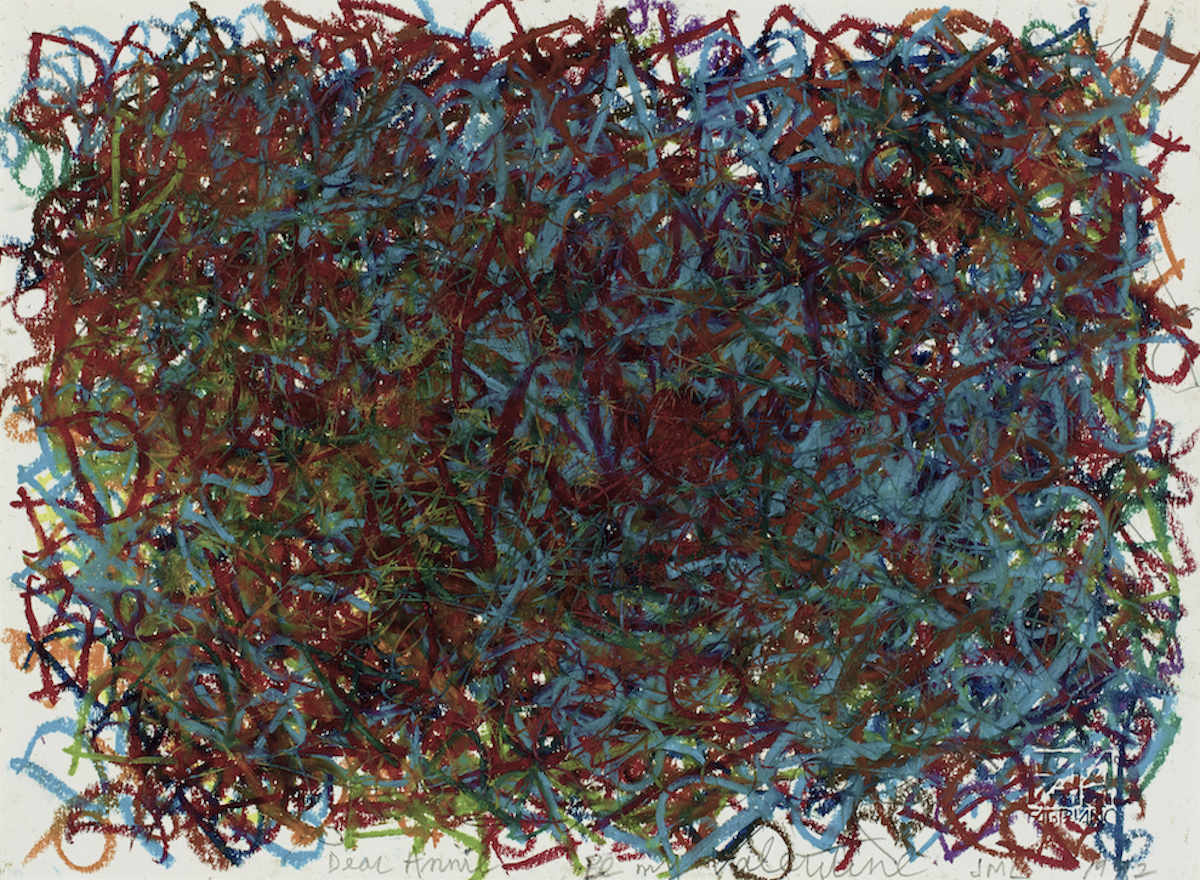

Jackson Mac Low, Dear Annie, Be My Valentine, 1992.

‘Sticky Bread Gets Sliced’ is number 108 in the Forties series that American experimental poet and composer Jackson Mac Low was working on in the last decade of his life, before his death in New York City in 2004.

When I read the poem I take the title as a cue and consider each of the eight stanzas as a tranche of ‘Sticky Bread’ (whatever this is…dense? doughy?), before learning that all the titles in the Forties series are formed by combining the first word with the last phrase of the poem. Just as all of the 154 poems are composed of eight stanzas, each following a similar five-line structure. There is always a compositional procedure at play in Mac Low’s poems.

I take several other lines as cues too – ‘nothing-disconnected’, ‘the smallest part or idea of it physical’ – and as self-reflexive keys to reading the somewhat disorienting poem that unfurls extraordinary lines and images, such as ‘a fenestrated melon’s hormonal horizon’, and ‘abstemious as mist after laughter’.

Unlike Mac Low’s other work that incorporates systematic chance operations or ‘non-intentional’ procedures, often using other material as source texts, the Forties poems are examples of his free writing where, as his partner, artist Anne Tardos, explains, ‘the poems incorporated everything he saw and heard and thought of at the time’. ‘Sticky Bread Gets Sliced’ however was not written off the cuff: the end notes state the poem was worked on in three bursts over a period of three years.

Primarily a performance poet, Mac Low’s poems, visual poems and artworks can function as notation or scores for performance. And in this poem caesural spaces signal the length of pause, hyphens between words signal that they are to be read quickly together (but not hurried), and the nonorthographic accents indicate stress. Voice and sound enter through these visual marks, reminding us that it is destined and designed to be read aloud.

Whenever I encounter Mac Low’s work I feel he is playing and making poems with pure energy. To read the poem is to chew it, to be alive to sound and language – exquisite, dense, surprising, full of wit and musicality – and to unexpected meaning. I consider it a gift that Mac Low made this ambitious free writing series after pioneering systematic writing methods (like the ‘deterministic’ diastic method, where he composed poems using an algorithm-like procedure by ‘reading through’ texts by Woolf, Melville, Stein, and others, attempting to move beyond ego and the self).

In ‘Sticky Bread Gets Sliced’, the space of the page becomes receptive, vibrant, like a ‘sticky decomposition web’ perhaps, where words, images, sounds lodge.