Grace Yee

A poem by Grace Yee from Chinese Fish

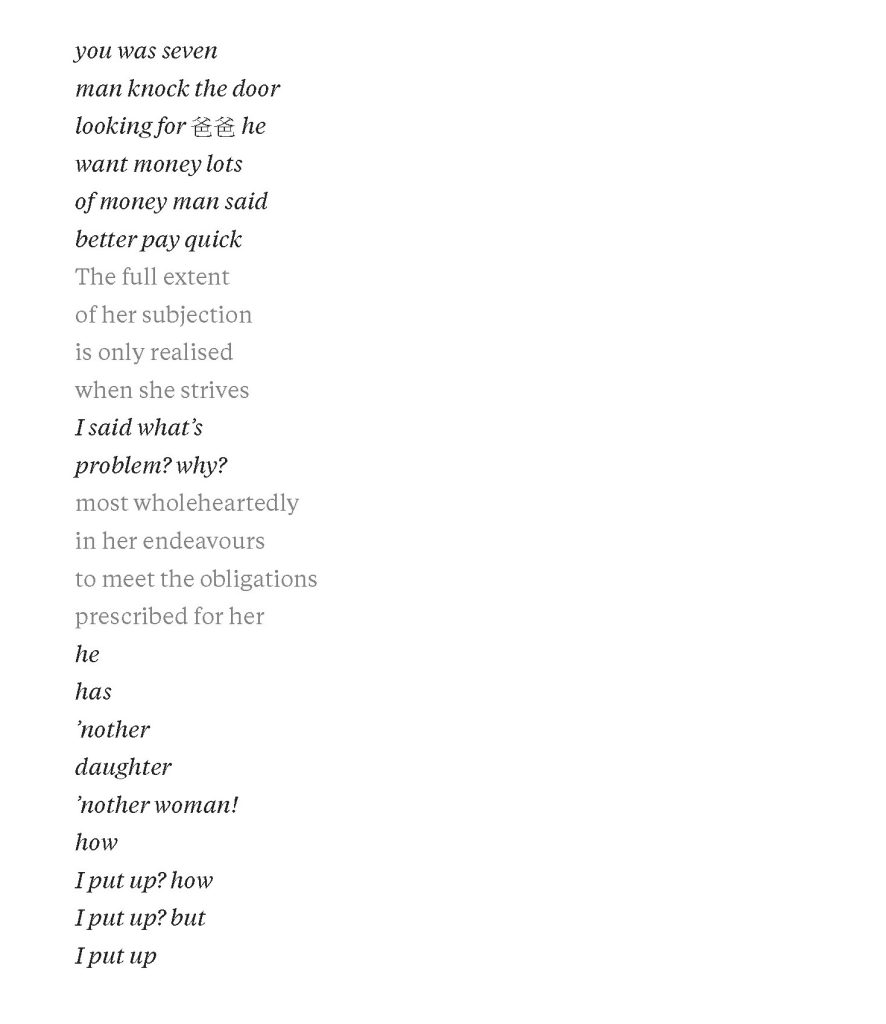

Read a poem by Melbourne-based writer Grace Yee from her 2023 collection, Chinese Fish. These lines (found on page 49 of the book) appear below as an image to preserve their unique typography, which signals to the reader a switch between the voice of Ping, a young Chinese mother newly migrated to Aotearoa New Zealand, and the ‘scholarly’ voice.

Grace Yee: a note on Chinese Fish

Melbourne-based writer Grace Yee reflects on her collection Chinese Fish, a genre-bending work that tells the multi-generational story of a migrant family in the ‘Land of the Long White Cloud’, Aotearoa New Zealand. The book was released in June 2023.

The title Chinese Fish is borrowed from a story published in the Evening Post newspaper in 1904, an extract of which I adapted for the opening poem of the titular sequence. The story, set in Wellington’s Chinatown, features an inspector, who interrogates a cook about some ‘strange and uncanny’ ‘fearful looking’ ‘specimens’ sitting in a bowl of water. The cook’s response, ‘Oh! Chinese fish!’ is an ‘inscrutable’ answer – a tactic – that deftly deflects further questions. The title may therefore be read as a descriptive noun phrase – an exotic hook – or as a verb phrase that brings to mind fishing, or angling, thereby assigning a sense of agency. In the latter sense, the title may be read as a synecdoche for a range of practices: what the settler Chinese in Aotearoa New Zealand had to do in order to navigate the insistently present orientalist narratives that circumscribed their lives.

In the opening sequence, ‘Happy Valley’, the use of definite articles to refer to family members is reminiscent of wildlife and anthropology documentaries in which fascinated voice-over narrators observe and monitor non-human animals and third-world humans. Some of the poems parody stock colonialist orientalist tropes and narratives, which variously exoticise, appreciate, infantilise and/or denigrate Chinese people and their cultural traditions. They include references to first-world/third-world dichotomies; transactional obligations such as tolerance in exchange for assimilation, benevolence for gratitude; the valorisation of saviour attitudes towards women and children. Most of the sequences in Chinese Fish are set in the most ‘English’ of Aotearoa’s cities, Ōtautahi, otherwise known as the Garden City, a ‘paradise’: the very antithesis of the impoverished squalor that many in the west imagined China to be in the middle decades of the twentieth century.

It is a little confronting to see the word ‘Chinese’ printed next to my name on the cover of this book. Because the settler Chinese community’s experience of this word was for so long associated with stigma, the instinct to refrain from making overt displays of ‘Chineseness’ and assimilate into the Pākehā mainstream was strong. The title feels a little treacherous, almost illicit: a talking back that flies in the face of the ‘model minority’ imperatives we were brought up with – be quiet, lie low, know your place – all of which were amplified for women and girls.

— Grace Yee