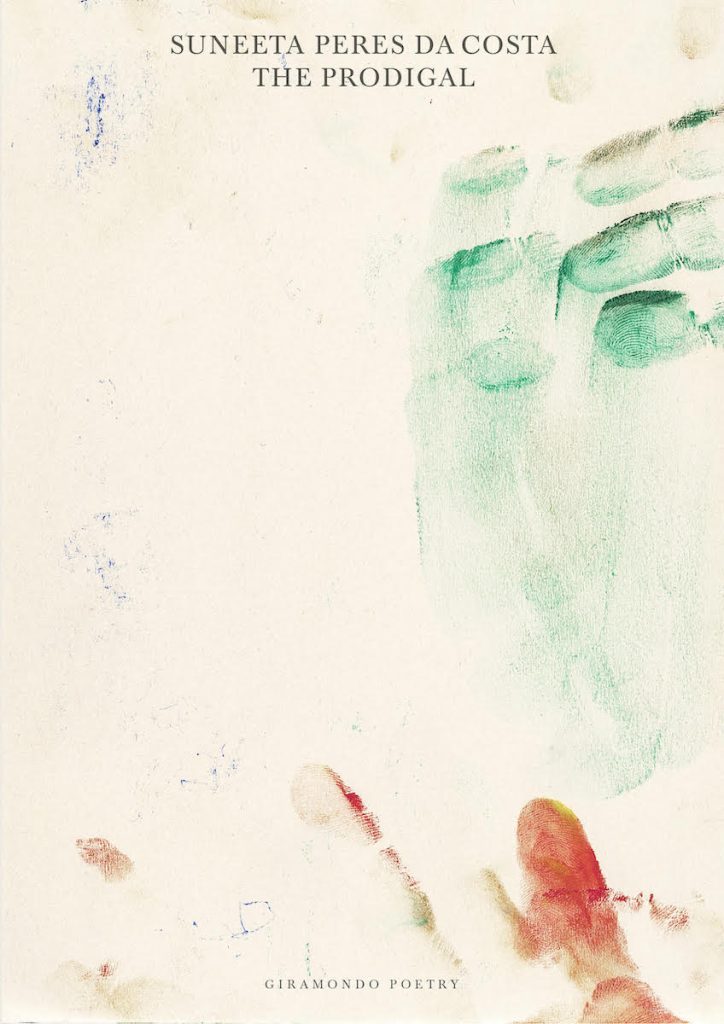

A poem from The Prodigal by Suneeta Peres da Costa

The Prodigal

Reeds stuck to her unwashed hair

and her cheek was bruised from sleeping

on the long string of tulasī beads she’d

bought at a temple stall in Tiruchirappalli.

Unbeknown to her they would tattoo

her skin in the night, writing their faint,

inscrutable calligraphy. No less than road

signs or stars or the compass of her GPS

(when the Airtel Towers gave signal),

she placed faith in the skein of these

wooden auguries. If they broke, she’d

weigh again the argument of freedom

over sanctuary, wild arithmetic that had

led her away from what was promised,

already hers. Her sandals – loose from

the monsoon – had been repaired at mochī

twice over; and the clothes she had taken

quickly, in the dead of night, slipping by

undetected while the watchman slept –

yellowed, grown threadbare. Legs sore

from wandering, she quenched her thirst on

salt lassis in random pure-veg restaurants,

counting her cash and days under the aegis

of goddesses with supernumerary arms.

Slick with yoga and āyurveda, their earthly

consorts flexed lissom torsos next door,

while a man whose legs belied all algebra

described exponential circles in the market –

his vāhana a makeshift skateboard. Stooping

to offer her leftover bhaji puri, she recalled

the rheumy eyes of the family dog Prabhu,

to whom she’d secretly feed breakfast rotis

under the table – later vomited in the yard.

In Rishikesh she entered the arms of a pilgrim

who, as he kissed her, whispered an Upanisad

of Isha: ‘He who sees all beings in himself and

himself in all beings loses all fear’ – but sensing

only her own anxiety, she soon took to the hills.

Through the window of a toy train, workers’

children played a game, balancing on steel rods

of a building site; between them, a celestial drop;

then mountains, ranges – called Dhauladhar.

In that last town, monkeys kept her awake, running

across the tin roof of the guesthouse and stealing

apples the caretaker’s wife, suspecting she was ill,

left out for her. One morning, instinct directed

her to a doctor on the town outskirts; a sign on the

grubby, scarred door thus qualified his credentials:

‘Sex determination of foetus not performed here’…

Afterwards, she kept walking, now and again resting

on hay bales, until farmers chased her away.

As she entered the river to wash, she realised it

was the glacial cover she’d seen earlier forming

the current and in its swift stream caught sight

of the bright wings of birds. It hardly mattered

she could not identify them by name, for their

choruses swelled in her, soon grew unmistakable.

The titular poem from pp.1-2 of The Prodigal.