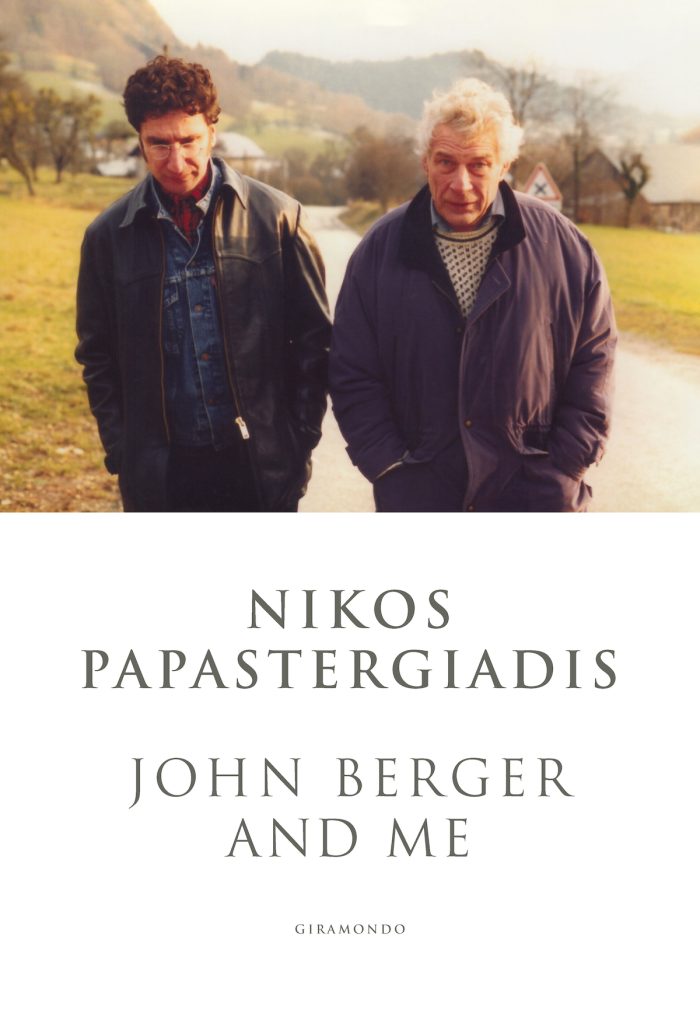

An excerpt from Nikos Papastergiadis’s John Berger and Me

The following excerpt is from John Berger and Me by Nikos Papastergiadis (1 August 2024), an eminent Australian sociologist. Part memoir, part biography, this book tells of the deep connections between the two, with the late English writer and art critic to Papastergiadis a mentor, father figure and friend.

A year before I met John, I had a lunch with Edward Said, the author of the magisterial Orientalism and the brilliant campaigner for Palestine. He talked with reverence about John’s work and even more warmly about John. Edward had a voice that flowed like a river but would creak and leap when he hit a rocky point of injustice. He was tall, broad-shouldered, and looked impeccable in a dark suit. And then he added:

‘But whatever you do don’t go and visit him in the village, there are pigs and shit everywhere!’

‘That’s fine with me, it sounds like my father’s village.’

It was the first time that the idea of visiting John in the village entered my head. At that point I was trying to work out the status of Ways of Seeing in my dissertation. I was given this book by my university friend Michael Healy. He was a poet who had just returned to Melbourne after a year in Berlin. In sympathy with my irritation at what Aby Warburg called the excessive empiricism and petty formalism of art history he sneaked a copy in his dungarees and walked out of the university bookshop. The moment I started reading it my mind blew up. At last, I thought, a real comrade in art and politics.

…

I once asked John why he never bought the house in Quincy from Louis. He was clearly very attached to it. His desk was upstairs by the window at the end of the bedroom. On this small table was a checked tablecloth, with just room enough for a couple of A4 sheets, an Indian ink bottle and another book. He used a Sheaffer fountain pen. Yves pointed out to me that Schäfer in German means shepherd, which of course in French is Berger. In the kitchen there was a pot-belly stove with a long pipe that kept the room cosy in the winter. The wood was stored under the verandah. They even installed a hot shower decorated with the odd Delft tiles.

So why didn’t they buy it?

John replied: ‘I have no wish to. This predisposition in myself – because it is almost a repugnance – served me very well in my relationship with the peasants who are my neighbours. I have noticed that whenever a peasant sells his house to say a Swiss family so that they can use it as a holiday home, and no matter whether it is a fair price, there is always a lament in the contract; the peasant feels as if he has betrayed his ancestors. It is felt as the illegitimate taking of something that if justice existed belonged to them.’

…

Not long before I arrived in Quincy, John’s chimney caught fire and the house almost burnt down: ‘It was a question of two minutes. Had it not been for all the neighbours who came with water the whole thing would have gone. As it happens the damage was not very great. Knowing that Louis would hear about it very quickly via bush telegraph, I immediately went to tell him. His reply was “Well as long as you are fine, it’s all right.” A couple of months later I went around to pay the rent which he refused to accept. “No. I don’t want it. You use the money to buy the things of yours that were burnt”.’

I don’t want to give the impression that John and the peasants had a monk-like disregard for material possessions. Artists, especially photographers, often gifted their work to him. Anya Bostock had the perspicacity to keep the painting by Fernand Léger when they separated. John treated each piece with great care and attention. As he stared deep into an image he would sigh, rub his thumb and index finger together, then an insight would flash in his eyes, and finally, a string of metaphors and similes would tumble out.

In the house in Quincy there were very few images that adorned the walls. There was an enigmatic poster of the pregnant Madonna by Piero della Francesca (Madonna del Parto 1460) that was glued into the arch under the verandah. The original painting was a fresco for the modest chapel of Santa Maria di Momentana. It showed the Madonna, patron saint of pregnant women, in a long flowing blue gown. Her hand is resting on her protruding belly. There is a slit in her gown revealing a cream-coloured under-dress. Two angels, one on each side of the Madonna, are holding up a damask canopy. The arching of the curtains draws the eye to her delicate and bent fingers that touch the slit. The poster was still legible even as it had peeled and faded in the harsh weather.

Inside the house there was another poster that was loosely framed, tinged in nicotine-time and watermarked, as if it had once served as a table protector. It was dedicated to Orlando Letelier, the Minister of Defence in the Allende Socialist government of Chile. The photograph shows him being frogmarched by a dozen armed soldiers. Their guns pointing at his back and their helmets shining in the morning sun. Orlando is in a dark suit, flared trousers, white shirt, with a wide floral tie. His head is upright, and his moustache is unflinching. The prison guards tortured this guitar-playing minister by breaking his fingers. A year later he was released. Soon after he was appointed as Director of the Transnational Institute where John and Teodor Shanin were research fellows. He continued to call for the downfall of the Chilean junta. The military ordered his assassination. His car in Washington DC was detonated by Cuban exiles. Below the poster is a poem by John about the quiet valour of this man. It ends with an invitation to come to the village:

He has come

as the season turns

at the moment of the blood red rowanberry

he endured the time without seasons

which belongs to the torturers

he will be here too

in the spring

every spring

until the seasons returning

explode

in Santiago

– John Berger, Sept. 1976

From pages 30-36