SlipzonesThe Politics of Pleasure in Art Writing Today

A few months ago McKenzie Wark’s Higher Education column in the Australian (June 25, 1997), described Robert Hughes as the curmudgeon of contemporary art with his failure to catch and refract the variable lighting of the art world in the 1980s. Likewise Stephen Feneley, on the ABC’s Express, who poked around the same issue, asking Hughes if this blind spot could be a generational thing? Perhaps, conceded the conscience of High Art Modernism.

Forgive me for age-essentialising some sixty million people but generational turnover can be a serviceable orienting device. Take a look at the last three chapters of Nothing If Not Critical where Robert Hughes attacked artists like Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and theorists – the precieux ridicules – like Jean Baudrillard. The poet-laureate of TIME magazine is a man with shaping enthusiasms too late for counterculture, too early for Postmodernism.

At the 1990 Adelaide Festival, Hughes got some easy laughs at the expense of the theorists. In a performance that reminded me of Orson Welles selling sherry, Hughes stood for lost ‘universal values’, for a lost imperial centre and earlier times, while strangely coterminous with a younger self. It was a call for contemplation against the commodity, the atelier system over the Warhol factory, lost originals over reproduction, substance over style, nuances of meaning over philistine social display. Along the way, like the Alexander Pope of SoHo with eucalyptus leaves in his hair, he fired rounds of buckshot at trusteeships to Museums, ‘lifestyle’ journalism, teaching ‘constipated with theory’, and criticism that grossly inflates the language of Art in its attempt to justify everything, no matter how trivial.

Hughes’s erudition and style are stunning. But underneath there is all the tonality of a rant, making it difficult at times to distinguish between the heft of moral judgement and pique. There is in his prose-persona a touch of the testy pukka sahib. Apparently some aspects of America – especially the Lower East Side of Manhattan – can make Australians behave 500% Roman Catholic Archbishop.

It’s not as though others didn’t think the 1980s were a hot air balloon. If you ask me, any decade’s self-conscious and venal ‘art world’ can be nauseous. There are inexorable forces that require one or two to be ‘great’, to represent their era, to have their moments of glory consolidated into permanence by the vast institutional machinery of museums. We didn’t need Charlie Sheen as stockbroker to see a Schnabel as no more than a commodity either. At least since Rembrandt, according to Svetlana Alpers in Rembrandt’s Enterprise, artists have understood that if you buy their work, you are buying a share in their reputation.

For Hughes the 1980s were a time when careers were mobilised by money and opportunity, depending for their success on media recognition-factors while encouraging a hit-or-flop mentality. To make matters worse there followed fretful commentaries by hypochondriacs of ideology. Signs and symptoms of impropriety were everywhere. Meanwhile, Hughes has been fostering his own counterculture of complaint – the ‘Cassandra critics’, a kind of Neo-Conservative Liberation Front, whose members wear their neckties around the forehead. A subculture, which seems to give our art journalists here, the John McDonalds and the Giles Autys, with notepad and smirk, yet another excuse for censuring the pleasure of others.

In case you hadn’t noticed, the art world, like the literary one, is not a community; it’s a fairly savage social and economic zone where values are in conflict. There is a proliferation of taste-cultures these days and so within the art world there are sects of intense belief, who put that extra zing behind values in common play. All objects, all words, exist in a network of trust. Often these sects mistake themselves for the mainstream. Like Les Murray and his sub-human pink-naped brethren, goosing the network that runs though the words – ’myth’, ‘mate’, ‘monoculture’, and ‘divine redemption’. Outside these networks, you are made to feel like a mountebank or prankster. Hence a certain ferocity these days in our art and literary scenes, with a reluctance to give contending practitioners the benefit of the doubt.

Contemporary art, often art before its time, needs some understanding and support. In competition with Rock and Roll, stand-up comedy and other things, it is too fragile to attack so arrogantly. Writing criticism is an inescapable part of the structure of power. Not a make-or-break power, but the kind of clout that comes from an influential paper, with too few reviewers and too few rivals. Hopefully the critic’s power will not run to gratuitously lethal comments, but take the form of dialogue. Artist and critic involved in a common enterprise, doing their bit for pleasure in a complex and terrifying world.

For someone of Wark’s generation and predilections, Hughes’s passion mobilised against mixed-media art, and beyond it to the cyber or digital re-organisation of the image world, seems archaic and quaint. To that generation, Hughes’s handicap is not only a preference for the contemplative in art, limited to the vehicle of painting, but an inability to establish a context with regard to other media. Especially the catch-all spirit of installation art, with its wildly additive approach to the cultural junkyard. It is as though the Hughes sensibility – despite the glories of style – is not theirs either. His mode of access – connoisseurship – is a dandyish desire, strenuously cultivated and slightly masochistic, registering all the nuances of brushstroke etc. Hughes comes across as more your straight man who might pound the ivories after a few cocktails and regale his guests with show tunes. Still, we are all partial to our own experiences, otherwise why bother?

Hughes’s world. Wark’s world. Me? I’m pulled three ways: toward Hughes, so crafty and wise; toward Wark, so astute and media-savvy; and toward a compromise which should offer the artist a richness of formal or empirical description with a worldliness of context. Hence my pleasure at a recent book by Terence Maloon and Simone Mangos, nothing …… will have taken place …… but the place. But more of that at the end of this spiel.

Qué pasa? Two things: a lament for the loss of a human-scale public space; and ‘for that tissue of meanings that sustains common discourse’. In other words, the society of spectacle and the ascendancy of theory.

But how public was the public space? High culture, from the Court through to Church, was for the privileged few. In hushed, wood-panelled halls, or quiet museums, you absorbed the mountain-peaks of civilisation, written and painted by geniuses, usually male.

By the 1960s, mass forms – movies, pop music etc – were so pervasive it was impossible for you to insulate yourself against the flood. Television, less a medium than an environment, fully saturated homes, bars, motel rooms.

Societies produce not only commodities for consumption (food, music, sport, fashion and so on) but also consumers for those goods. The hierarchy of cultural goods reflects the social hierarchy of consumers. A lot about art and literature is about how you take your pleasure – do you dissemble your enjoyment? Do you display it?

High art was for individual appreciation, popular culture was into mass release. But if commercial culture has its numbing effects, the classics – out of context and austerely imposed – can be pretty good tranquillisers too. Pop culture dissolved the values of the dominant interest group with its trademark features of one race, one class, one gender. While post-modernity is defined today by its ability to mix all ages and tax brackets into a tossed salad of segmented desires.

Culture was this thing apart, with a wedge put between what is lived and what is learned. This tension has led to a do-or-die struggle between a conservative cultural agenda, and those pedagogic forces trying to reground culture in everyday reality. Accusations of ‘decline in standards’ and ‘hotbeds of specialised subversion’ took an ugly turn in America (see Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind, Roger Kimball, Tenured Radicals, and Dinesh D’Souza, Illiberal Education) and here in Australia too, we’re feeling a rollback with drastic cuts in funding to the Humanities.

While Hughes may or may not accept the collapse of cultural hierarchy, he’s hypocritically resisting the mechanical means of reproduction. Sure, it’s easy to tell that Rembrandt is art, but what criteria do you invoke when assessing a giant tube of toothpaste? After Warhol walked into the supermarket and signed Campbell soup tins for a fantastic mark-up, post-Pop culture has had to learn How to Stop Worrying and Love the Commodity. Or at least address it.

Much recent art takes for granted a bilingual grasp of both ends of the cultural register, both high and low, erudite and streetwise. Art has mostly thrived on flux and opportunity – look at the careers of Daumier or Courbet. Countless artists exploit the creative possibilities between high culture and low (from Dickens and Poe and Lautrec, to Godard and Dara Birnbaum).

The savant-expert role that Hughes embodies is always in danger of turning into the Dandy – no less precieux than the ridicules he trounces. The Dandy is a snob who wants to crystallise life into a perfect form, or literary style. Choosing and achieving so ‘deliberately’ has blinders of its own. Unlike Kruger and Holzer whom he vilifies, he is blinding himself to the politics of information and its contested terrain. Laurie Anderson, for example, minority mixed media artist of the 1970s, sold 150,000 copies of her LP Big Science through Warner Brothers. The strategy, according to the wily Bertolt Brecht, is to hijack the ‘bad new things’ rather than genuflect towards the ‘good old things’. Plugging into the power surges of ordinary fantasies while trading on the established vehicles of expression.

I don’t wish to be a reverse snob, but writing for TIME Warner magazine means that as custodian of dying universal values, it’s hard for you to be just-and-free for all. TIME operates globally via Intelstat and OTC. Page-proof positives translated into digitised information in New York are Pagefaxed to Melbourne so fast that a complete copy of the magazine – a reproduction of the original, not a copy – with local editorials and ads, can be sent in a 12-hour satellite transmission window.

Isn’t Hughes taking for granted that he speaks to the world in a magazine that itself is like typographic TV? That his precious art must be contextualised with the trivial stink of demagogically-slanted news up its nose all the time? Is his anger provoked by the fact this kind of outlet is precisely where the vacuum of the 1980s art world meets the unspoken void of the masses (readers of TIME, watchers of TV)? That it commodifies consciousness in a particular way, prefers interview-thought and instant-thought, and forces you to talk in sound-bites? That his rhetorical position is the result of a particular mass media address: the ready-made studio audience waiting for the usher to hold up the placard to tell them when to applaud?

It’s a price we pay to become part of the pantheon of celebrities within the communications industry. Nothing wrong with it: it is a society we create for our own consumption. It borders the academic and the press, literary and para-literary. Part of the establishment, but also united in contesting it. Attacking ephemerality and purveying it, parlaying about it. The Clive Jameses and the Robert Hugheses – are they stretching the received (industrial) definitions of what art/TV/scholarship are? Or are they merely entering a new yuppie mass market? That place in the late twentieth century where values get sucked through the vacuum of the media and where post-modern myths are not merely defined, but certified.

Under the influence of photojournalism and television, our ability to distinguish truth, fact, and opinion is now heavily reliant on visible proof. The tragic demise of Diana in Paris, and the to-do about the evil-eye of the paparazzi, gives us pause. A visual artist, like Barbara Kruger or Cindy Sherman, can consider such consequences in ways the mass media can’t: the poignant impossibility of transcending subjectivity with even so objective an instrument as the camera, and the failure of subjectivity to affect the world with even so anonymous a medium as photography.

One insight to value from theory is that no text is innocent and no language transparent. Back in the 1930s James Joyce, in Finnegans Wake, was one of the first writers to tackle this experience of language in media space: thought, feeling and action carried on by unrealities in a totally unreal context which only spectacle makes plausible. Signs become atoms of dreamlike verbal sensation: a 24-hour barrage of infomercials, slogans, captions, jingles, platitudes, and what Jenny Holzer in the 1980s called ‘truisms’. Holzer exploits this nullity behind words – as any newspaper reader, or TIME magazine reader has experienced it – by making us feel that some of her lines have been exhaled by an LED machine, rather than by a person (SOMETIMES ALL YOU CAN DO IS TURN THE OTHER WAY. STASIS IS A DREAM STATE. PAIN CAN BE A VERY POSITIVE THING.). No ideas, no emotions, no facts, no proper language, and yet communication happens.

A lot of the scaled-up theatricality of work in the 1980s (the artist trying to impress, according to Hughes with ‘short-impact conceptualism trying to be spectacle’) includes work by Anselm Kiefer, Leon Golub, Imants Tillers, Juan Davila among others. It was a way of making short-lived clearings in the media swamp. It is a response to the squeeze, the admass sandwich that blows you up and flattens you out. Like them or hate them, Kruger and Holzer are examining the language of this era when TV makes life an indefinite elsewhere, and where casual social exchanges feel more numbing and complicated than alienation.

Contemporary art and literature, then, is part of the expanding world whose constituents will simply not mind their manners or keep their place. Images these days happen in a continuum of visual experience with TV, video and the computer screen. Books don’t seem to fit easily inside the neat categories you find in bookshops. Is it autobiography or fiction? Documentary or memoir? High or low?

Much contemporary art is a bit too worldly for the polite lust of the connoisseur or the headache-inducing world of academic theory. By ‘worldliness’ I mean the application of common taste, acquired from looking not just at art, or texts, but at the world and everything.

The paradigmatic change can be seen as a shift from the gemstone model of art (to borrow a useful distinction from Donald Brook), to the model of art as a birthday present. (In other words, it often doesn’t matter what the gift is so much as the occasion for the gift. Anything can be a gift if given in the right spirit.) When Marcel Duchamp put his bathroom fixture in an art gallery and called it Fountain (1914) he questioned the rules by which art was made and expanded its possibilities. The work was not about its meaning, it was about its function within a given context. Art history is still reeling from the pitiless matter-of-factness of non-art objects finding their way into the sanctified precincts of the museum. Isn’t every object regardless of its merit as art (an Appalachian banjo, an Islamic coin, Chinese dragon bones, a 12″ LP, a lunar module) of potential interest, value to, or insight into, the culture of the age?

After Duchamp’s ready-made, after Minimalism and Conceptualism, the frameworks for the viewing experience and the critics’ languages for mediating it, have proliferated. Before that, the public displays of Enlightenment art, down to the vocabularies of Modernism, were an uninterrupted line. The art object was autonomous but required for viewing it a class-specific mastery that derives from a kind of medical inspection of the canvas, modulated to a pure gaze that grinds your attention down to a fine grit; this seems gone with the myths of high art and a patrician aesthetic. The space for viewing has expanded beyond the museumised categories of painting and sculpture.

It follows that for the art writer too the role has changed emphasis. Hence the bleatings from the Cassandra critics who feel an entire caste is going down the gurgler. The shift has been made from the scholarly humanist tradition of the art historian (humanistic values, Western cultural tradition), to the cultural critic, attacking the myths of high art and historicizing the values. This is McKenzie Wark’s world. Meanings are not natural, they are constructed. The cultural critic asks: what’s the game and who is it for? Which leads to this crucial set of understandings – (a) How we read conditions what we read. We read selectively from an angle based on our sources; (b) There’s no functional relationship between the instrinsic richness of a text (read artwork) and the richness of the discussion it can support. Umberto Eco on James Bond, or Philip Brophy on B-grade movies, are much more compelling than connoisseurial discussions dawdling over colour tones and abrasions on a flat surface.

A sociologist like Jean Baudrillard is less interested than Hughes in contemporary art as a twenty-five-year feat of cultural engineering with channel systems fed by scholarship, criticism, journalism, PR, tax deductions and museum policy. With McKenzie Wark, Baudrillard sees most art as high-end interior decoration. Baudrillard’s interest is in how artists – especially Duchamp, Warhol, and Koons – outsmart the logic of capitalist production. A strategy of the counterfeit, not parody. Forms are being grasped at once, while content and its attendant mysteries do not exist except as a commentary on the capture of form. Like Taiwanese copies of designer labels. For the market deconstructs itself faster than a Marxist can say ‘infrastructure’, it widens and swallows all opposition: so how otherwise do you tackle it as an issue? Pop culture theorists, in their turn, believe the neo-conservative art critic belongs to a superannuated tribe of unreconstructed Frankfurters with a nostalgia for pre-industrial folk art.

As for Hughes’s injunction for ‘a tissue of meanings that sustains the public life of art’? Baudrillard belongs to a sizeable discursive community: just check out most bookshops.Theory, once so specialised, underwent startling demographic changes. The glacial page-time of academic publishing has now picked up speed. The ready-made categories of knowledge have shrunk, and after Roland Barthes and Umberto Eco, the potential market of young multicultural big-city readership is ‘competitive’ in every sense. Observe the extraordinary career of Umberto Eco, the first Professor of Semiotics but best known, as the academic hitmaker whose multiplatinum smash, The Name of the Rose, was made into a film starring Sean Connery.

In the twenty years Hughes has been writing for TIME Warner, our world has become increasingly a classroom culture, a culture based on knowledge industries. The regrouping of scholars ran the old disciplines at highly eccentric angles to each other, with recondite methodologies like psychoanalysis, semiotics and post-blahblahblah emerging. Unfortunately not theory, but theoreticism – the mistaken attachment to system – has hindered rather than facilitated a more responsive approach to the specifics of art. This systematisation of reading and writing as social practices takes place in education. It has led to both the professionalisation of the college-educated artist and the professionalisation of criticism. The command of Theory, the subcultural dialect of ‘Theoryspeak’, begins to confer social rewards and influences.

Theoryspeak (as opposed to ‘Layspeak’) is the special way art is talked about (read and discussed) in universities and art colleges and what the students get out of them. A lot of it is a bit like a foreign language. Once unthreatening paintings and sculptures are texts and installations, sites of contestation and inscriptions of subject-positions. Layspeak is more the kind of thing you use writing for TIME, or translating for television audiences, but there is no fixed border between T-speak and L-speak. Often what was once specialised (like the word ‘paranoid’) becomes L-speak. Today you hear in basketball they ‘deconstruct’ an end-zone.

Jargon gets laughs. It can block thinking and sail past the obvious sometimes. Jargon, common everywhere from law to administration and electronics, comes across as mystery-fakery and suggests intellectual self-indulgence. You can end up teaching Art Theory as a Second Language. People do. Outside the class context you may as well be speaking Albanian.

By now we feel that theory has taught its lessons too successfully. Over the last fifteen years there has been an accelerating production of language about language. Like every other system it operates under the law of entropy – everything gets more difficult, never easier. Why? Because there is no other direction left. I’ve read catalogue essays that read like Derrida with food poisoning. Hughes quotes from a catalogue by New York curators, Richard Milazzo and Tricia Collins in American Visions. I agree: this writing is deconstruction with a dentist’s drill. Talk about the displeasures of the text.

By over-privileging philosophy you atrophy description. You lose direct contact with the work, as well as that strange but salutary effect of feeling naive. Naive in the sense of running into the brick wall of the work’s radical materiality, its zone of silence. In that zone you are no longer hostage of your own premises.

In some ways, I concede, Robert Hughes is right. We’ve got a whole lot smarter but no wiser. Sociologising art culture and moralising the sociology had become just as overbearing as the commercial pressures through the 1980s, but way less fun. It has led to a growing divide between some artistic practice and critics. With the loss of the artist’s studio-derived considerations (the death of the author) we’ve lost another layer of the experience: the murky dynamics of creativity itself. Eliot said we had the experience but missed the meaning. Today many have had the meaning and missed the experience. But Hughes too is setting up a lose/lose situation by slighting some of the potent work created by contemporary artists.

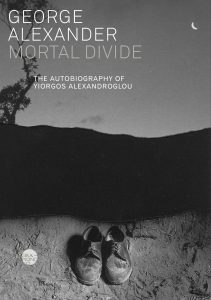

Which brings me back to Terence Maloon’s essay in nothing …… will have taken place …… but the place, a monograph on Simone Mangos, an Australian installation artist based in Berlin. Maloon was the best art journalist we’ve had here, generating in his Sydney Morning Herald reviews a complexity of tones in a small space: praising without hype, and criticising without gratuitous radioactive comments. A serious critic able to straddle generations of artists, and as comfortable with painting as with installation. Maloon, for example, was able to fend off inter-generational polemics by bridging painterly abstraction as practised by artists like Michael Johnson or John Firth-Smith, with the conceptual use of it by Imants Tillers or John Nixon. The latter were diagnosticians of the image. This helped, rather than hindered.

So with installation. Which has become something of a bugaboo or joke these days in the press. Installation joins forces with the critique of commodity culture embodied in unsaleable works – Conceptual Art, Process Art, Earth Art, Minimalist Art, Performance Art – either from the 1970s, or their scattered reprise in the 1990s. It dismantles the tidy groups of spatial experiences we associate with museums, those neat rows of eye-level art, by forcing us to enter other spaces and take in other information. Installation transforms the foursquare stable place used by architects into an existential or actualised space produced by a viewer.

Installation is the experimental prose poem of the visual arts, an unforeseeable bastard offspring of all the misalliances that constitute experience. Disjunctive but nonetheless emotionally compelling installations can be tiny, intimate, discriminating habitats or uncorked environments of violent theatricality. Installation is art finding new ways to go on despite frightening historical discontinuities. With society turning all experience into a form of consumption, is it still possible to be moved?

Installation connects with the empowering forces of indigenous cultures (folks who have been making vernacular versions of installation all along), or makes us aware of our crippling forms of absent power (like dharma or voodoo). At the same time it plugs into current metaphors of techno-immersion (like ambient music or omnidirectional acoustic space; interactivity, virtual reality).

Women artists have been drawn to the half-charted world of installation in significant numbers. The big blown-up macho space of heroic sculpture is side-stepped – in a countervailing feminist strategy – for an inclusive, immanent space responding to the inhabited environment. While each artist’s efforts in this area are as intimate and revealing as handwriting.

Simone Mangos’s extraordinary work celebrates this scavenged, ephemeral, shipwrecked aesthetic. In the unforgettable Well (1986), Mangos used a whole fresh pine tree, uprooted, covered in honey. The atmosphere was just as heady downstairs at the Roslyn Oxley Gallery in Sydney, where a single wooden bed, surrounded with pine needles, was filled to the brim with honey, and on it lay a pure white pillow.

Writes Maloon: ‘Hers may be a variant of the ‘art of the real’, where a tree is a tree, a salt-pillar is a salt-pillar and a net is a net, yet viewers of her installations will rarely if ever experience these things literally – the elements in the installation are obviously laid out for divination, for sensing, for fathoming.’

There is a psychological, even moral quality to inhabited space that Gaston Bachelard detailed so eloquently in The Poetics of Space. The space we inhabit is never geometric, but oneiric. ‘Space’, he writes ‘is compressed time.’ Think of the daydream-soaked house of childhood. The heady intellectual space of the attic, the basement into whose subconscious levels we descend with a metaphorical candle even in the age of electricity. They each conjure a super-sensory, even sub-sensory, dimension: centres of boredom or reverie or silent beholding.

This is art less about observation, than ways of connecting processes. This shift from an art that describes to an art that connects breaks from a clenched Western tradition of the formal function of artefacts. Ordinary objects carry a spectral meaning as well as the obvious ones. Daniel Spoerri talks in awe of the still warm loaf of bread he found on the side of an autobahn after a fatal accident. A strange voodoo attaches to certain personal objects. Why, for instance, do we tear up the photo of an ex-, or treasure it for that matter? Hex signs? For Aboriginal Australians the mundane object made of stone, cloth and wood – the tjuringa – can run power through it like an electric light. And some people are the earthly batteries for those energies.

Though it helps concentrate the mind, the white cube of the gallery is a place deliberately deprived of location. Installation returns power to the site, as well as physical scale to the body. It takes issues beyond the universalising white cube with its track lighting, and provides a structure for dealing with the hard questions about contemporary reality that left to its own devices will savagely outstrip the arts-palace model of culture. Importantly it gives artists the chance to work ad hoc with materials and apply downstream problem-solving. This in contrast to the mainstream tendency to deep engineering and shallow ideas.

Installation reflects a polyculture, rather than a monoculture. Photography, video, painting, sculpture – all the mediums of installation – shed their autonomy. The object itself is not the work but the system of relationships. These may be informed by a range of disciplines – information systems, archaeology, astronomy, ecology. Disciplines that, left to themselves, fall silent on matters unprovable.

Art, suggests Maloon, generates ideas, it doesn’t represent them. Art of this kind can attack on two fronts, with both sides of the brain. Maloon moves smoothly from the textures of the outer world which is politically specific to the resonances of the inner world. He captures in this work, shifting politics and sociologies and is not against asking tough-minded historical questions. Mangos’s Tolling Läuten, for example, in Berlin’s Prinz-Albrecht-Gelände is a counter-monument, evoking memory and resisting it also. Maloon writes that the work ‘dispelled the oblivion of the white cube and effected the restitution of a sense of place…a place fatally compromised by history’. Tolling Läuten is a stacked rise of rubble from that area in Berlin where the main offices of the Gestapo, the S.S. and Reich Security were located from 1933 until its bombing and devastation in 1945 – a taboo area corresponding to a profound trauma in Berliners’ communal memory. Collected and painstakingly washed by the artist, the porcelain, bricks, metal objects and glass deformed by fire, were set precariously on a platform hung from a steel cable, which was in turn attached to a wall that had been detached from its fixed position and made to lean into the space.

How can we rationalise the emotional weight of this? What do we do with it? We don’t put it through the wringer of semiotics. You learn the theory (let’s say of Freudian screen-memory) then ditch it because, as Guy Davenport pointed out, ‘Imagination is like a drunk who loses his watch and has to get drunk to find it again’.

The works of Simone Mangos, austere, yet enveloping, leave language in this state of suspension. Not that they’re undiscussable, but they require as much silence as talk. Is it possible for criticism to use what is essentially the method of poetry? To offer cracks, ledges and handholds for the imagination? Objects operate by a kind of visual shorthand. To command an object’s potencies is to oversee magic: what do you make of a rifle covered with feathers? a tepee covered with dollars? a black bag with the letters H2O stencilled on it? What do you think of when you see ex-Yugoslav performance artist Marina Abramović continually scrubbing a human skeleton on five video monitors? Things I’ve encountered in installations, but given short shrift by our reviewing brethren.

As Maloon shows, a poetics of thinking offers many counter-strategic insights. Playing fast and loose with poetry’s reserve of metaphors is another way of getting your head around a work. One half guesses, half understands the work of art, forcing language into a dance of veils, shifting its threshold each time in order to survive the consequences. Words debate the images which compel an opening upon perception. Perception that gets inside you and makes you be and know and grow, and maybe, if you’re lucky, intensifies your sensuality too.

Robert Hughes, Nothing If Not Critical, Selected Essays on Art and Artists, HarperCollins, 1991

Robert Hughes, American Visions, The Epic History of Art in America, Harvill Press, 1997

Terence Maloon and Simone Mangos, nothing …… will have taken place …… but the place, Louis Verlag, 1996