Published January 1999

Become a subscriber

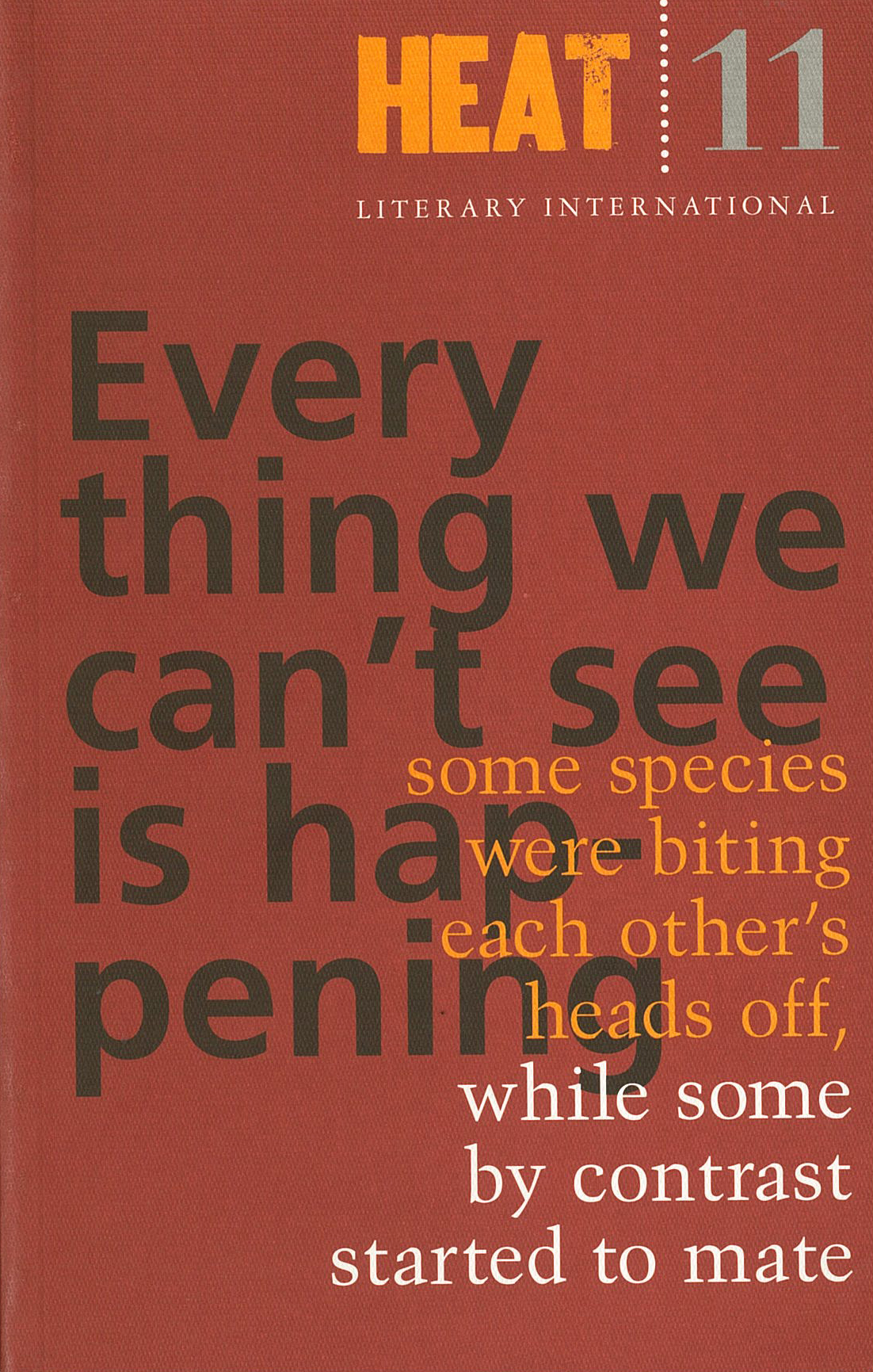

Ark

Translated from the Danish by Roger Greenwald

I was writing a long and labyrinthine poem in which I opened up and at the same time stepped into that openness, stillness, with a white voice as word after word drank from its stream, and the further the poem extended the more difficult it became, its syntax gradually transforming according to mathematical principles no one had ever revealed to me, but the words’ reciprocal contacts reminded me of leaves that the wind has caused to sing in the air, and this meant that the poem must be written in a single unbroken chain if its meaning was to hold, its language kept tightening in constantly new patterns, in which certain words demanded ritual repetition in such a way that both a male and a female began to appear in the surrounding lines, one male and one female, until a great many species had arrived in the poem, where they demanded their place, even though it was practically impossible to accommodate them in the stringent system that was virtually constructing itself when a friend my own age showed up one day before my desk of gopher wood and asked about my next book, astonished at finding the room full of animals and me so young, just as I was amazed to see his hair in a white wreath around his head, a frosty crown of age, and while we exchanged smiles and spoke the language of truth, as we had always done, the animals continued to sneak in through a window behind me, two by two, so without my being aware of it, my study had begun to resemble a zoo—I had just kept writing the poem and hadn’t noticed birds of all kinds, cattle, wild game and vermin, because my desk with its many drawers was raised high on a ledge, almost a platform, in the vaulted room, but there were in fact a myriad of animals that had found their way there and had come in pair by pair, male and female animals that I knew quite well but other species too had arrived as I wrote and together we began to capture these animals, especially drawn by a type of yellow frog whose croaking must have given the poem its tonal modulations, but each time we tried to get hold of one, it evaded us and I became aware that I had developed a certain aversion and didn’t like the idea of touching all the animals that were streaming in through the open window and down the wall, out across the floor where they continued their wandering in long files up toward the platform with the desk: animals I had been fond of in my childhood now suddenly made me insecure, I was unsure of their characteristics, shapes and precise relations to one another, I didn’t recognize their ways of reacting, couldn’t recall if they bit or stung, secreted a dangerous poison or were just harmless creatures, but my friend was fond of them all, both the slimy and the scaly ones, handled them and moved them around so they wouldn’t hurt one another, some he set atop the desk as a sort of unformulated commentary on the poem, which after all wasn’t finished and at once I was afraid that its structure would start to craze if I didn’t take it further right away, so I returned to my seat but at that moment the water outside began to rise, and the animals clambered pair by pair up onto the platform, and from there up onto my desk, where I labored to put the higher mathematics into speech by continually deciding what should go into this poem and what should come out, while the water rose all around so even the highest peak under the heavens was underwater, the animals were still alive, but the chaos was growing great upon my desk, where some species were biting each other’s heads off, while some by contrast started to mate, and when nature thus before my eyes repeated itself in an endless number of each species, as well as an unlimited number of unforeseen variants, and moreover developed a whole series of new races that I had no names for, the result was soon an abundance of irrational proportions that further complicated the poem as did the noise from the many species, roars mixing with chirping, humming with snorts, whinnies with bleating, howls with weak hissing, but the worst affliction was the yellow frogs, which sounded now like cicadas and now like rattlesnakes, and whether the animals were growling for food or in chorus awaiting the conclusion of my poem was impossible to tell, because I was preoccupied by intensifying pains in my right arm and I would have hated to close the poem now, when it was changing at so fast a tempo that it made me realize mathematics probably didn’t have much to learn from me and my longing for infinity: I wrote from sea to sea, but there wasn’t room for all the animals, I understood that it was limitation that was endless, my right arm stiffened so I could work only slowly and with difficulty, the poem was to form a knot that no one unversed could untie but at the right tug on the sentence-threads, with one shoulder toward the sky, it nonetheless came loose with ease, only to reveal that in the world of the spirit there is no completed entity, and just then I noticed that the water had penetrated the whitewashed room but the animals were safe on the desk under the vaulted ceiling and the water hadn’t reached the ark, where everything wasn’t quite gathered yet but I had gotten far enough along so I could speak with my friend and say how happy I was that he’d found me in the midst of the enigmatic notation that would lead to this poem, which still wasn’t very legible because of the many corrections I’d made underway and was hard to keep in order since I was continually making revisions, until after a time, at the sound of a bird’s cooing call outside the window, I looked up and saw that the water had retreated, that the light no longer merely seeped in but was here—it filled the room, and only then did I decide unequivocally not to include anything more, but to concentrate on the multitude I had taken onto my ark, relieved that the paper wasn’t the least wet, as if during the ceremony it had lain protected in a small chest, I saw a bow in the clouds and laid aside my fountain pen, I hadn’t eaten or slept or gone to the toilet while I’d written, hadn’t seen a single person, but now someone was addressing me again, and I felt I must respond; everything occurs as it occurs, and my friend, sitting before me, marveled that my dress remained freshly pressed and white.