On Guan Wei

Australia is an unusual country – a big island with strange animals and plants. It would not be surprising if eggplants had evolved here. They are very mysterious. I can imagine dark purple eggplants growing against the yellow sand in the desert.

Guan Wei

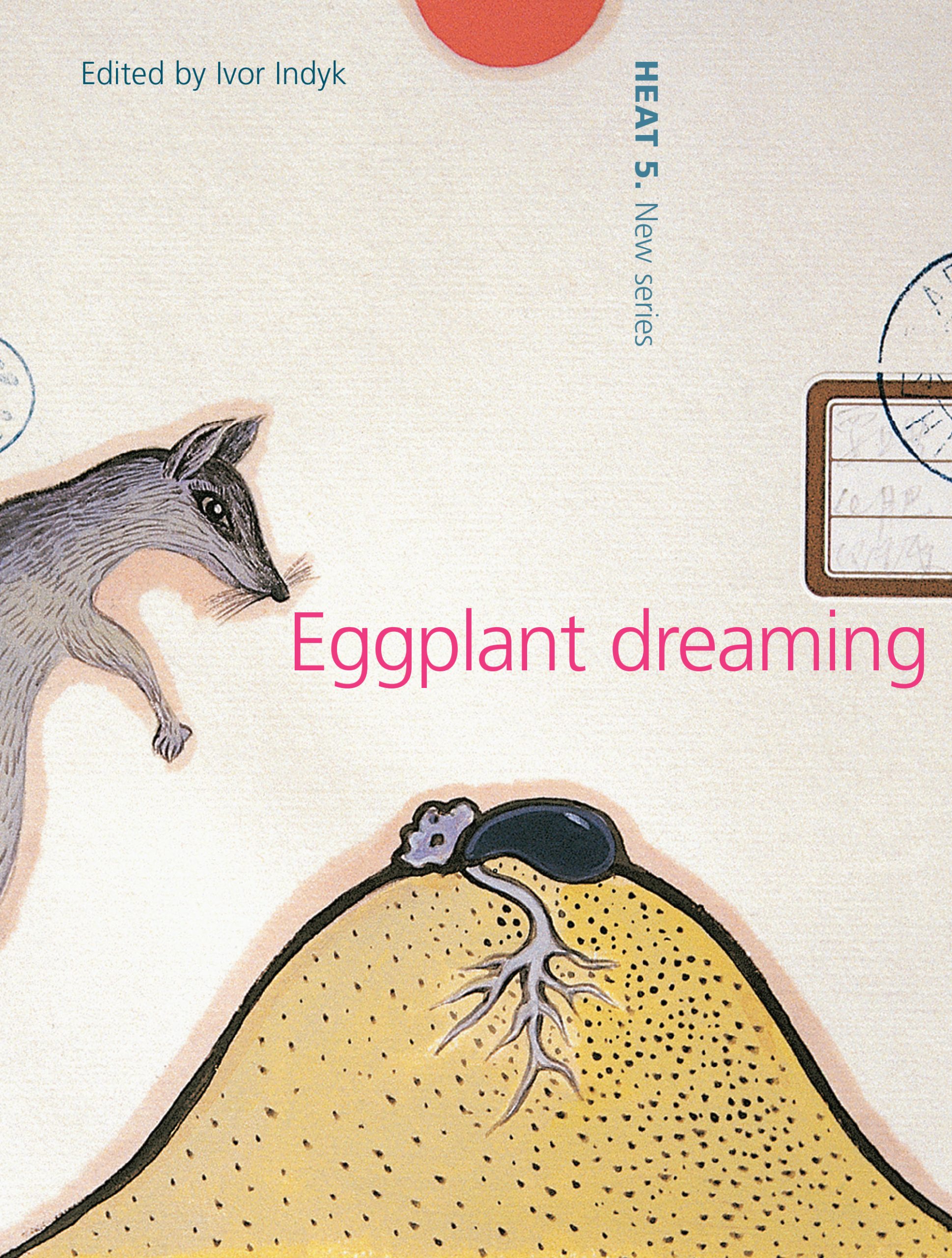

Sydney-based artist Guan Wei’s Method for Eggplant Cultivation is a concertina book covered in silk brocade that opens to reveal a series of ten paintings. Each page illustrates a stage in the development of an eggplant growing in the Australian desert, from a sprinkling of seeds, through the processes of sprouting, flowering and reaching maturity, until it is picked. The book is both a fantasy horticultural guide and, more broadly, a cautionary tale about the introduction of foreign elements, including people, into new environments. The book’s sequel, The Prevention and Cure of Diseases in Eggplants, ostensibly a guide to aubergine malady, also alludes to the potential outcomes of environmental manipulation and cultural transplantation.

Born in Beijing in 1957, Guan Wei first visited Australia in early 1989 as an artist in residence at the Tasmanian School of Art, and returned to live here in 1990. He was a child when the Cultural Revolution began in 1966 and just finishing high school when it ended in 1976. Like many of his generation, Guan Wei then went to work in the countryside. He worked as a labourer but dedicated his spare time to painting and drawing. Guan Wei returned to Beijing in 1979, just as the effects of the Open Door policy began to be felt. Art schools and universities had started to reopen and ideas, books and people from outside China were once again able to enter the country. Guan Wei read as much as he could about the world beyond China including books on science, art and philosophy, as well as fiction. During that time he also experimented with a range of Western modernist painting styles and became a high-school art teacher, a position that gave him the opportunity to concentrate on his own artwork.

At that time I painted a lot of my own sort of pictures, pictures about how I felt and about my friends, family and colleagues. Also at that time, China was changing and many foreign people began to be interested in buying and looking at art in China. I was in a good position. I could earn money from my job and from selling my pictures to foreigners at the same time. I also had a lot of opportunities to communicate with foreign people, including artists. It was a very interesting time.

By the middle of the 1980s Guan Wei’s distinctive style, with his deliberately flat application of paint, use of long narrow canvases (initially due to an opportunistic recycling of old window frames as stretchers), his division of the picture plane into horizontal sections, and the recurring depiction of stylised, often ghostly, naked figures, had started to develop. He was also producing paintings and drawings in series, an approach that remains characteristic of his work.

Figures with Acupuncture Points (1985–7) is one of Guan Wei’s earliest series. The group of seventy oils shows figures painted in black and grey against a darker grey background, their bodies marked in red with acupuncture points and Chinese characters. The fingers of the otherwise featureless figures are long and expressive. Guan Wei often uses hand gestures to help tell his stories, a trait he attributes to the ways in which such gestures are used to relate narratives in Chinese opera, an art form he learned as a child from his father, who was an actor in the Beijing Opera. Two Finger Exercises, a series created in the months following the tragic end to the pro-democracy demonstrations in Beijing in 1989, also centres on hands. Struck by the potency of the simple victory sign so often seen during that period, Guan Wei included figures making the gesture in each of the forty-eight works. The unidentified cloud-cuffed hand that plants and picks the eggplant in Method for Eggplant Cultivation has a similarly powerful presence. It represents a sort of deus ex machina, contributing to, rather than untangling, the ambiguity of Guan Wei’s plot.

Other constants – beakers, capsules, sausages, test tubes, babies and eggplants – are also used within series to convey narratives. The Living Specimen series, begun in Tasmania in 1991, uses liquid-filled beakers holding icons of Western art, including Duchamp’s urinal, Magritte’s pipe and Botticelli’s Venus, to ‘make some jokes for the masters’ and to communicate Guan Wei’s experience of living in a new country with limited understanding of the language. As he described the situation: ‘I was living in Western society, but on the inside of my body was Eastern culture. I felt very isolated, like I was inside a glass filled with water.’ In Treasure Hunt (1995), a large drug capsule with unknown contents is protected by Australian native animals and aggressively pursued by one-eyed characters apparently descended from the figures with acupuncture points, an adventure that can be interpreted as the continual quest for achievement and meaning in life. Believing his art should be polyvalent and as appealing to the mind as the eyes, Guan Wei’s works are rarely without intricate story-lines.

His work has a particular soft-edged humour and sense of folly that closer examination often reveals as a lure for something more serious. In addition to the personal and social experiences explored in series like The Living Specimen and Two Finger Exercises, Guan Wei is concerned with environmental and political issues and is fascinated by scientific developments, particularly genetic engineering and mutation. Roller Creatures (1997), for instance, charts the effects of industrial waste on the evolution of a species of insects through a series of mock scientific diagrams. Each canvas in another group of paintings, Test Tube Baby (1992–93), features a buoyant Chinese New Year-style baby holding a test tube and floating above a beaker containing a genetically modified vegetable or fruit. Created via a process of experimentation, Guan Wei’s babies grow up to become his Wunderkind (1993) who in turn undertake their own scientific research. Dow – Island, a monumental forty-eight panel painting completed in 2002, shows three main islands, ‘Calamity’, ‘Trepidation’ and ‘Aspiration’, as well as a group of smaller islands and surrounding waters. The sea is filled with mythical creatures and boatloads of people desperately trying to sail to safety. Guan Wei adapted the painting in the months leading up to the 2001 Australian federal election to include drowning figures as a protest over the Australian government’s response to asylum seekers trying to reach Australia and the exploitation of the subsequently discredited ‘children overboard’ scandal.

Though he is known primarily as a painter, artists’ books, drawings, prints, paper constructions and installation pieces are also integral to Guan Wei’s artistic practice. The books Method for Eggplant Cultivation and The Prevention and Cure of Diseases in Eggplants were first exhibited opened out as wall scrolls in ‘Guan Wei: Nesting, or the Art of Idleness’, Guan Wei’s solo exhibition at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art in 1999. They were created as part of a larger installation that included a grid of twenty-four eggplants resting on mounds of sand, various types of eggplants floating in giant beakers and a propagator box of seeds. Titled Reforming the Desert: A Plan, the installation presented an imaginary experiment in making the desert more hospitable by growing eggplants in the sand. While this playful piece hinted at Guan Wei’s concerns about damage to ecological balance through ill-considered intervention and orchestration, it also acted as a metaphor for the changes brought about in people and places as a result of the processes of migration and relocation. In a statement about the installation Guan Wei wrote:

One of the main reasons that led me to the development of this work is my ‘experience’ of Australia well before I arrived. From a very young age I read about Australia, which I consider to be a very uncanny continent on the earth. The plant and animal life here is unique. In particular, illusions and images relating to the central Australian desert are continually in my mind. To draw upon scientific methods to reform the desert is a wonderful reverie for me.

Guan Wei populated his book Method for Eggplant Cultivation with kangaroos and emus as they are the animals he associated most strongly with Australia while living in China. In reference to the astonishment and wonder he shared with the early colonists in encountering Australia’s extraordinary wildlife, his depictions of creatures draw on late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century images. Guan Wei’s kangaroos, one of which has a joey in its pouch, are based on the kangaroo in George Raper’s 1789 ink and watercolour work, Gum-Plant and Kangaroo of New Holland. A midshipman on the First Fleet ship HMS Sirius, Raper was also an active amateur illustrator who produced numerous views of the new colony. Raper’s shipmate Able Seaman Jacob Nagle is quoted as having written about the creatures they encountered, ‘There is pillicans, and ducks, and different kinds of animals, but the kangaroo is the chief…The she have a fals belly…’

Method for Eggplant Cultivation’s first page shows the large cloud-cuffed hand planting seeds in a mound of sand under a bright sun. From there the pages alternate between day and night scenes as the moon waxes and curious emus and kangaroos visit the burgeoning mound. They keep watch as the exotic little plant sprouts and forms a bud that opens into a lotus-like bloom before receding to expose a tiny foetal eggplant. The shiny purple fruit grows and grows until it is almost as large as its visitors when, under the full moon and with a kangaroo just departing the scene, the hand returns from the sky to pluck the eggplant from the sand.

Each page in the book is meticulously painted and ornamented with rubber stamps and stickers. The book’s title is stamped in blue on its gilt-flecked titlepage using the letters from a children’s stamp set. The titlepage also features a red star and a series of seals of the sort used on Chinese calligraphies. One is Guan Wei’s name seal, another reveals a nickname ‘talkative’ and a third reads xiang ru fei fei, or ‘fanciful thoughts’. The large irregular-shaped seal on the left of the page is a Zen saying, ‘A mosquito bit a steel cow’, which has to do with going ahead with a venture despite knowing that it is pointless. According to Guan Wei, ‘traditional painters have many seals symbolising their philosophies and status as intellectuals. I like to use the seals to make little jokes because in China there are a lot of stamps and the bureaucracy is very complicated.’ He also makes use of the utilitarian paper stickers and labels available from stationers and has applied them to a number of his works on paper including the suspension-file series Detective (1995), Secret Garden (1995) and Mapocalypse (1996).

Guan Wei started collecting stamps and seals in China in the mid-1980s and now has over 200 precious and everyday stamps from China, Japan and Australia, as well as some he has carved himself. The lower section of Method for Eggplant Cultivation’s first page features a ‘This is not art’ stamp bought at the Salamanca Markets in Hobart. Throughout the book are administrative stamps bearing characters that say ‘document’, ‘secret’ and ‘check’, as well as an adjustable office stamp set to print the Roman alphabet. A number of Guan Wei’s seals were inherited from his father who practised calligraphy and ink painting and actively fostered his son’s interest in the arts.

Guan Wei’s father’s name seal appears in blue in the lower right corner of every second page in the book, on the pages marked with blue dot stickers. The blue dots at the bottom of the pages indicate night, or yin, scenes and the red denote day, or yang times. Yin belongs to the dead, to the realm of the ghosts, and yang is for the living. The number of stick-on dots progresses from one to five on the first five pages then descends from five to one, indicating an entire cycle and creating further symmetry for the book and its carefully balanced images. The same formal qualities, the black margin around each image, the horizontal division of the space into two unequal parts, the central mound, the sun or moon directly above it and the stick-on name label and blue seals, appear on each page of Method for Eggplant Cultivation.

Eggplants first appeared in Guan Wei’s work more than a decade ago. They appeal to him for their colour, shape and sheen and because they have an element of danger. According to Guan Wei, eggplants are considered slightly poisonous in China, a liability eliminated by cooking them with garlic.

I first had the idea to make a work about eggplants many years ago when I was asked to make something for the Adelaide Festival. I wanted to create an installation of eggplant stories and I made up a fake history for it.

Hundreds of years ago, a mysterious boatload of people sailed to Australia from the east bringing eggplants and garlic with them. The land was very rich and desirable but the people from the east were not strong enough to take over the country so they decided to try something devious. They gave the people of Australia eggplants and garlic but didn’t tell anyone that they needed to be cooked together to combat the poison in the eggplants. They hoped the people would get sick and weak. War broke out between different groups in Australia over possession of the new foods, which weakened their position against the explorers even more. That war became known as ‘the Battle for the Eggplant’. Around the same time, a westerner travelled to China to find out the secret of the eggplant. There he fell in love with the king’s daughter who taught him how to use garlic to make the eggplant safe to eat. Afterwards the traveller went to Australia and shared the secret.

Guan Wei’s proposed installation for the 1994 Adelaide Festival was inspired in part by the story-line of The Rose Crossing, a novel involving the meeting and crossing of English and Chinese cultures in the seventeenth century, that his close friend Nicholas Jose was writing at the time. Comprising invented maps, historical texts and objects, as well as a sculpture of a giant eggplant and garlic nestled lovingly together, Guan Wei’s piece was not selected for inclusion in the Festival and was never realised.

Recently, however, Guan Wei has returned to the idea of creating a mock history and is in the process of developing a new work, Re-creation of Relics – the Pioneering Discovery of Australia by the Chinese. The installation draws on the artist’s existing eggplant history and the research of controversial British historian Gavin Menzies, whose book, 1421, The Year China Discovered the World (Bantam, 2002), argues that Chinese eunuchs sailed to Australia almost 600 years ago.

In the meantime, eggplants have been a regular motif in Guan Wei’s work and are the major players in The Great War of the Eggplant, a twenty-panel series painted over the summer of 1993–94 while Guan Wei was artist in residence at the Canberra School of Art. Ten of the panels tell a story about eggplants travelling out into the world from India in two directions – the first through Tibet, China and Japan to Korea, and the second through the Middle East and Europe with Italy as their final destination. The lower section of each panel in the journey includes an illustration of an eggplant dish from the corresponding country. The dishes are based on recipes from around the world collected by Guan Wei as part of his research for the series. Eggplants are used as objects of trade and markers of cultural interaction and change in the series, as well as in place of humans as the main characters in the drama. The other ten panels of The Great War of the Eggplant feature stories about the personal lives of the eggplants, their battles, escapes, romances and children.

The Great War of the Eggplant, Method for Eggplant Cultivation, its sequel The Prevention and Cure of Diseases in Eggplants and the larger installation they are part of, Reforming the Desert: A Plan are, as much of Guan Wei’s work is, elaborate fantasies or puzzles reflecting contemporary issues. Method for Eggplant Cultivation looks not only at ideas of environmental transformation through the introduction of foreign species, but at creating a life and flourishing in a new place before being snatched from the earth. The eggplant in the book, like those involved in the great war, can be seen to represent a human life. A carefully designed, painted and embellished book with a cheeky wit, Method for Eggplant Cultivation is also, as Guan Wei notes, ‘a wonderful reverie’.

Information about Guan Wei’s work in this article is drawn from interviews Melanie Eastburn conducted with the artist between 1997 and 2003. Material relating to George Raper can be found in The George Raper Collection, National Library of Australia (Canberra, 2000).