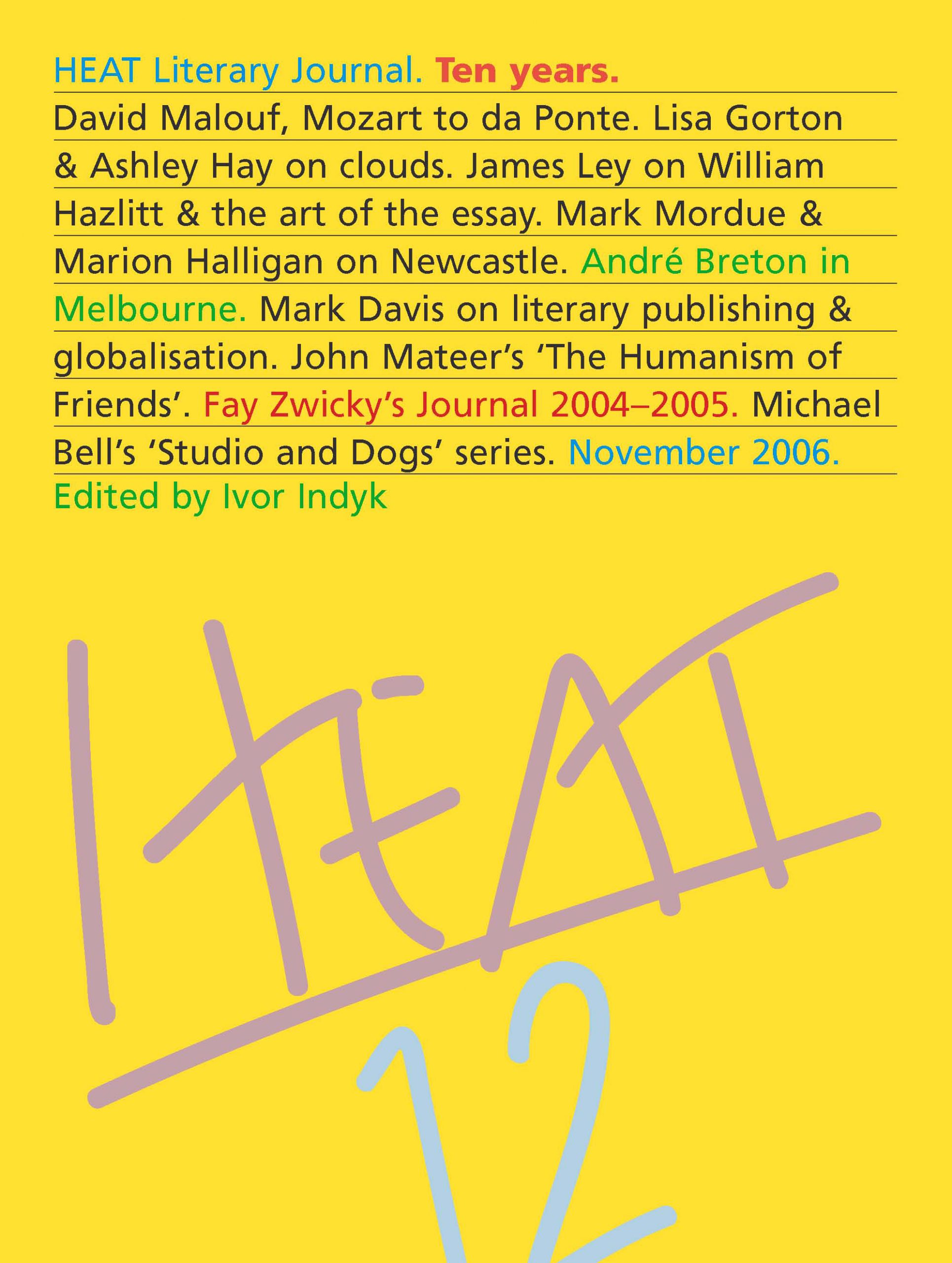

Journal 2004–2005

Probably lots of writers who keep journals stop and reflect on how awful they must appear. Sassoon wrote a poem on the egotism of diary-keeping, ironic of course:

This was the truth, as near as I could get it,

Although the truth is truth to me no longer.

But dead misapprehensions make me stronger

Who am infallible now and no more blind!

Then mummied thoughts seem vivid and exciting:

For (like a vast percentage of mankind),

Myself’s myself’s main interest: so I find

Not one dull page in all these reams of writing.

I don’t agree, having often stopped to reflect on my own dullness and obtuseness: I’ve never thought that what’s written indicated a unique person. Merely a woman survivor who likes to chat, often far too loosely and uninformedly to make her anything other than a scribbler of the Johnsonian breed. How I wish I had something other than the usual set of delusions common to septuagenarians with a shaky grasp of reality, insights repetitive and intelligence limited. I’m sure that, if I could only weld it all together, I have a story to tell that would extract from the raw chaos of a long life a truthful making of some kind of sense. As V.S. Pritchett said about the memoir, ‘It’s all in the art. You get no credit for living.’ To sort out the notion of self as the organising principle, the entity that gives shape and texture, propels the narrative, offers direction and unity of purpose. Who, exactly, is this ‘I’ that nudges the memoir into being? It’s a search in the act of writing: the process of becoming is revealed through selection of circumstances that shaped the self – the bringing to consciousness of what was formerly inchoate and unnamed. Valuing the flotsam of one’s own past and sifting out the chaff is what’s to be done – what counts in the end is not the company of ghosts that haunt me but the work embodying their exorcism. So far, I seem to do this best in poetry.

And whom do I feel most akin to, stuck out on this edge of a desert, my family gone, friends dead, sick or mad? Cavafy, ageing in Alexandria – who else? Remember ‘The City’? A dialogue between two friends repeats the dilemma in stoic, flat finality, like Chekhov’s loopy sisters forever yearning to get away from the provinces:

The first speaker lets fly (?), laments his exile from some mythical home:

How long can I let my mind moulder in this place?

Wherever I turn, wherever I look,

I see the black ruins of my life, here,

where I’ve spent so many years, wasted them,

destroyed them totally.

The second speaker puts paid to whatever delusions his friend may have about greener grass: it’s as if two halves of myself were speaking for it’s exactly the sort of inner dialogue that accompanies every day of my life in Perth:

You won’t find a new country, won’t find another shore.

This city will always pursue you.

You’ll walk the same streets, grow old

in the same neighbourhoods, turn grey in these same houses.

You’ll always end up in this city. Don’t hope for things elsewhere:

There’s no ship for you, there’s no road.

Now that you’ve wasted your life here, in this small corner,

you’ve destroyed it everywhere in the world.

The repetitive neurotic yearning, the statement of cutting awareness of the futility of trying to escape betrayal and disappointed hopes in a more congenial place among more congenial people. Romantics always want the promise, not the fulfilment: older ones can live simultaneously in hope and disenchantment, can live in poetry and prose without really accounting for time’s passing, managing to get stuck in the past without ever quite acknowledging the present. You can know your own delusions quite thoroughly, without much chance (or even inclination) of relinquishing them.

You can’t deceive an old dog who knows that the master’s journey was the best part, the entering of new places for the first time, the summer mornings of vanished childhood among birds and cicadas. Even if now incapable of being lured or deceived, the goal begins to seem less attractive: what made it once wonderful was its mystery – and youthful ignorance:

Wise as you will have become, so full of experience

you’ll have understood by then what these Ithakas mean.

You can be both disenchanted and bewitched when old – there are no obvious contradictions in these states because you don’t care anymore what people think. Your self-importance, anxiety, aspirational selfishness have been stripped away by age and exile. You can say no to so much that once you would have put up with for whatever specious injunctions you thought society required you to validate. You’re not obliged to resolve contradictions, however comforting the thought, and however much resolution is promoted as necessary to mental health. Perhaps it’s just not given to everyone to achieve harmony in old age. It’s one of those myths that proposes reconciliation and serenity as the mark of maturity, e.g. Shakespeare’s Lear had to become The Tempest, Rembrandt’s portraits of young men become luminous with enlightenment of mortality etc. What about the disjunction of Beethoven’s late quartets? Tolstoy’s very late break for freedom to the railway station at Astopovo? Ibsen’s angry last plays etc.? Are these the doings of wise and composed elderly sages? They are riven with rage and contradiction, beaten down with irresolution yet intransigent to the end.

In Cavafy’s poem, ‘The God Abandons Antony’, history gives the poet (via Plutarch) the great moment in the Roman hero’s life as he faces the loss of everything that once mattered to him: his hopes, his physical prowess, his sex appeal with its cheap regrets and facile self-deceptions. And, finally, the city that once nurtured the prime of his life – Alexandria: he is enjoined to look hard at that place whose life he once shared and was feted in – a pageant in which he is no longer a shining light and whose consolations he can no longer call upon for reassurance:

Go firmly to the window

and listen with deep emotion,

but not with the whining, the pleas of a coward;

listen – your final pleasure – to the voices,

to the exquisite music of that strange procession,

and say goodbye to her, to the Alexandria you are losing.

That’s the ultimate, most profoundly dignified goodbye to life I can remember reading. No false elevation, no grandiosity – just the stoic, hemlock-taking farewell of the enlightened sensualist who craves no longer. It’s quite Zenish in a way, and I must remember to read it often enough until it can’t leave my head. It’s the point at which poetry and prose become almost indistinguishable from each other. You can replicate your sense of exile in poems that hand over meaning to the unknown reader while denying its compensation to yourself – like the selfless teacher you once hoped to be. You’re too shy to be part of the action, and remain apart. But you see things, and what you see is a world outside to which you know you’re only remotely connected in one sense but bound indissolubly to in another. I’m burbling – time for bed: it’s after 3 a.m. and it’s so seductively silent and black outside. And within.

Bertrand Russell told a meeting of the Heretics society in Cambridge (founded by William Empson) that the Ten Commandments were like an examination paper and should bear the rubric: ‘Only six need be attempted.’ Now that’s realism!

Graeme Murphy became a ballet dancer and choreographer of considerable flair. An article this morning tells of his formidable mother, an ebullient pianist who bashed out everything from deportment class accompaniments, christenings etc. to the classical warhorses. ‘Her great talent was that ability to pick up on the mood and play to that. She knew if someone was a bit arty and musical, she’d pull out the big rep. The power of a woman with a piano is to be reckoned with, I’ll tell you.’ Think of D.H. Lawrence’s poem, ‘Piano’ as I’ve so often done, remembering my own childhood crouched under the instrument while Debussy’s ‘Cathédrale Engloutie’ engaged my (probably depressed) mother on high. Murphy has just produced a new work, Grand, inspired by his mother’s spirit, the music as shamelessly eclectic as his mother’s repertoire. The article describes it as a ‘muscular meditation on the relationship between the piano and dance.’ A very ‘personal work…for me, she and the piano were linked, almost physically connected.’ He even played an old cassette she’d made at her own funeral ‘full of energy and life and bashing out classics and some singalongs…I made sure one of the pieces had a big bum note in it so that the gods wouldn’t be too angry: the gods don’t like perfection. It was a beautiful ending because the family were all there.’ Wonderful stuff…

I like the idea behind Murphy’s ballet, setting up thoughts about what to do with my own mother who began life dancing, armed with a spectacular back kick that landed the toe of her ballet shoe on the back of her skull. Deriving creative energy from the mother, an endless Australian story that runs like a powerful undercurrent through the murky waters of this benighted country’s history.

‘A literary spinster, with a pen for a spouse, a family of stories for children, and twenty years hence a morsel of fame, perhaps; when, like poor Johnson, I’m old, and can’t enjoy it – solitary, and can’t share it’ (Louisa May Alcott, daughter of Transcendentalist, Bronson Alcott, whose house I visited in Concord). She was no fool. More, surprisingly sharply self-critical, regarding most of her novels as merely ‘moral pap for the young’. Her Little Women created in the hearts of generations of women just what a happy girlhood looks like. Her own beginning was somewhat different: she had to forge her own luck as her family came from the class of ‘silent, poor…needy but respectable, and forgotten because too proud to beg.’ Bronson was above providing for his family who moved house (according to his wife) twenty times, always looking for cheaper rent or a more favourable prospect. Like Chekhov, Louisa ended up supporting the entire family by her pen, doing her publisher’s bidding with an ironic aside ‘Anything to suit customers’ in her journal when cuts or plot changes were required. From such crucibles of deprived childhood come our myths about undisturbed relationships between parents and children, our models of dauntless females capable of sustaining a vocation alongside romantic love and adult responsibilities. Then a life is spent undoing all the nonsense while never forgetting the original catalyst with affection, regret, and much sympathy for the brave author.

C. Paglia has written another book about ‘The World’s Best Poems’ (her assessment); forty-three of them. Having grown up in a NY factory town among ‘speakers of sometimes mutually unintelligible Italian dialects’, she was attached initially to the language of her parents but grew to love English:

What fascinated me about English was what I later recognized as its hybrid etymology: blunt Anglo-Saxon concreteness, sleek Norman French urbanity, and polysyllabic Greco-Roman abstraction. The clash of these elements, as competitive as Italian dialects, is invigorating, richly entertaining, and often funny…

Poets often insist that they ‘love language’ but few actually validate that love by usage or appreciation. The nearest many come to true love is either an omnivorous indulgence or a constipated minimalism indicative of over-fastidious retreat from abundance. It’s hard to tell from her eclectic choices just what, apart from grafting popular on to high culture, constitutes good poetry – perhaps the phrase ‘hybrid etymology’ best describes the stylistic criteria used in her aesthetic evaluations. Sincerity doesn’t necessarily serve to distinguish good from bad art, regardless of what the current panjandrums of academe prescribe.

Smoking, again. King James I railed against it in pulpit language: ‘a custom lothsome to the Eye, hatefull to the Nose, harmefull to the Braine, dangerous to the Lungs, and in the blacke stinking fume thereof, neerest resembling the horrible Stigian smoke of the pit that is bottomlesse.’ Yet we still persist, lured by associations with dangerous beauty and theatrical self-regard, branded by dissidence, fired by the wilful adolescent need to defend pleasure against the forces of morality. What gives pleasure is equally intensified by the promise of risk, the gamble with/against boredom, the impulse towards life while dicing with death. Whether or not we’re on the path to perdition, smokers have created the best things in contemporary culture – films, books, plays, music (especially jazz) – none of this legacy is lightly erased from the cultural record despite the frantic efforts of the health police. What comfort remains is often in the discovery of a smoker’s sense of solidarity with others of this beleaguered minority. ‘A certain dark anti-glamour lingers outside the restaurant doorway as you and people you will never meet again enjoy the rough comradeship of exile, puffing away in your thin jackets in February as if you were doing something heroic’ (Luc Sante, in his book No Smoking). ‘As if’ is just about right for this most enjoyable of aberrations: I do seem to rev up creatively and leave the pits of depression far behind once back on the weed. Yet I still wish I’d kicked it after the last bronchial disaster and left it kicked…

A. went off on Saturday to see friends in Israel and England. I still have residual worry about her vague dithering and don’t know how much of it is real and how much assumed. Whatever the motivation, it certainly produces a high anxiety level in those who can’t live with excessive indecision: it’s the stuff of my nightmares – missed planes, ships, the paralysis of inaction, the confusions of ignorance. In typical older-sister fashion, I said in the goodbye phone call, ‘Use your head. You’ve been given one for survival. For God’s sake, use it!’ She laughed in that customary rueful dismissal of my reliance on ‘brain’, in that there-she-goes-again-telling-me tone which covers and defines a lifetime of difference between us. Neither is better or worse. Beckett’s Hamm in Endgame shouts: ‘Use your head, can’t you, use your head, you’re on earth, there’s no cure for that’, which pretty well describes my credo.

Why do we think a long life more worthwhile than a short one? If both end without meaning or purpose, then it makes no difference. To die before the lessons of adulthood have been grasped would have been, for me, a huge deprivation. That mirage of individuality, that travesty of freedom that informed my youth had to be faced for its fragility, falsity, and potential to implode. I don’t know that the word ‘happiness’ is much use to anyone in either sound or sense: its hemmed parameters don’t come anywhere near describing the daily enjoyment experienced now that I’m over 70 – and this includes a large variation in mood ranging from rage to serene calm such as I felt listening on Sunday to the Schumann piano quintet in the concert hall with Ben and the ASQ playing more seamlessly than I’ve ever heard it performed. The day was perfect, and all without strain or self-consciousness. How wonderful it is to be released from the corporeal self now and then, no pain, no struggle, no backward regret. What else can you call it but a little bit of luck, a moment’s respite: Hardy wasn’t a happy man but he saw things in a grand scheme – grimly masculine:

This fleeting life – brief blight

Will have gone past

When I resume my old and right

Place in the Vast.

(‘When Dead’)

The earth might be, most surely is, a ‘blighted star’ as Tess calls it, but sometimes, if you’re blessed to grasp it, the blight lifts and a clear pane lets in the light. There’s no cure for your span on earth but what can be made of it may amount to an unanticipated gift.

I’ve always loved Middlemarch, the perfect fusion of moral and aesthetic intentions. The last paragraph speaks of Dorothea’s ‘incalculably diffusive’ influence on people around her, ‘for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.’ I’m not sure what she meant by ‘unhistoric acts’ – are they those deeds that never make it into the history books? And what are the assumptions that lie behind the notion of ‘the growing good of the world’? If you’re neither a political reformer or social crusader, are the qualities that might determine ‘growing good’ more nebulous, more spiritual, harder to quantify or dissect? Anyway, nobody who understands irony could ever be suited to ‘historic acts’; their performance rests with ideologues, buffoons and demagogues and laughter is usually last on their agenda. Unforgivable in most writers: the only one who escapes is Tolstoy whose very being is a ‘historic’ act in every sense of the word. But even he managed to repudiate, in the most pig-headed way, the aesthetic values which make his great novels tower over the spectrum – so contradiction and perversity have to be taken into account when trying to determine greatness. If I had to decide between James and Tolstoy, I’d always plump for the latter whom James denigrated by calling his novels ‘loose, baggy monsters’.

Harold Bloom’s Western Canon is amazing, amazingly good and amazingly bad, with so many different styles bumping up against each other, so many unexplained critical terms, and much disdain for close engagement with the texts’ nuts and bolts. I remember struggling with his The Anxiety of Influence which seemed to have armed itself with an impenetrable vocabulary for a set of ideas that couldn’t make it past the steel spikes of the encampment. I recall a critic who likened Bloom to a sort of mountaineer of the Sublime in his book about Shakespeare: ‘The view may be great from the high ground, but, boy, is it windy up there’ e.g. ‘Inference in Hamlet’s praxis is a sublime mode of surmise’. Time and again, he’s up to his neck in clotted parodic language that gets under my skin and makes throwing the book away, breaking its spine, and murdering the author seem an easy option. He seems to revel in language of any kind, indiscriminately grasping whatever abstract floridity comes to hand e.g. ‘cognitive charisma which cannot be routinized’. The critic I once read (Lane?) likened exposure to the Bloom Vocabulary in The Anxiety of Influence, to being shown round a plant nursery stuffed with treasures like Tessera, Apophrades and Clinamen by ‘a gardener with a filthy mind’. I gather now they were only mock-classical: not the genuine province of mediaeval scholarly rhetoricians I originally supposed.

My original reaction to the book was a feeling of great inadequacy, a sense of having been left behind long ago by far cleverer practitioners of the critical persuasion I once thought myself capable of understanding. Even doing my own amateurish bit for the humanist cause! Later, I began to sniff a con and revered him less as I struggled through the obscurantist fog only to realise there was no view from the summit other than a desert, desiccated and lifeless, and a lot of gasping near-dead masterpieces blighted by the gaze of the Jehovian sage. In The Western Canon, all those words have gone and are now replaced by ‘aggressivity’, ‘overgo’ and ‘passional’, none exactly wrong but sufficiently out of kilter with what’s being discussed to get up one’s nose. If he’d only abandon the polysyllabic rebarbative pulpit manner and stay with the natural, conversational recollections, allusions to friends, enemies, etc., it would be a great salvationary trot through what he calls ‘the time of chaos’. Sometimes, he can be really insightful but I have to say he’s not in tune with Emily Dickinson whose poetry doesn’t exactly fit the volley-and-thunder scale within which he operates. I suppose none of these objections has stopped me reading, extracting whatever crumb of insight pops up and even coming to appreciate the sheer cheek and perversity of an old man who loves literature and loves talking about it. Come to think of it, I’m an old woman who likes doing the same thing but hope to do it in private these days without any messianic delusion clouding the view. I remember how much Gwen Harwood loved the book and recommended it warmly to me in between the jam-making and the demure pretences of housewifery. Stuck as we are/were in the Australian wilderness, we always cocked an ear for a kindred spirit who made up for the resounding silence and pussy-footedness of our ‘critical’ forums: Bloom, at least, kept us alert if not always in accord.

Reading is a solitary occupation, like playing piano. ‘We see literature best from the midst of wild nature’ (Emerson’s ‘Circles’). Silence and concentration – forget book clubs, chain stores, English departments if you want revelation. St Augustine wrote about being ‘dissociate from myself’ until he heard a voice summoning him to open the Gospels: ‘Pick up and read, pick up and read.’ A child’s voice, the event reminded me of Blake’s vision in ‘Piping down the valleys wild’.

This is probably why I’m most receptive at night, especially in the very late hours alone with absolute silence and the pool of bright light from the halogen lamp beckoning from its reflection on the white empty page. The thought-fox strikes after midnight. Thanks, Ted.

English as a study has come to represent some of the shoddiest aspects of our culture: posturing about sex, social inequities, the cult of celebrity. It shows up all the contradictory attributes of a religion in its final decadence: desperate to attract converts combined with a pronounced lack of conviction and belief in its own scriptures and traditions. It has become saturated by the market mentality it decries, expert in planned obsolescence, incapable of resisting the consumerism of the contemporary university where student-approval surveys control the inflation of their grades. There is a craving for great art, a yearning for what exceeds that which one has been able to articulate for oneself. For me, the contact with great writers has been indispensable and, as a teacher, it was my hope to pass on that appreciation to my students. I’m very happy that I no longer have to coax and prod and provoke in what passes for an English department today but sometimes I miss the stimulus of those few excellent minds I was privileged to tangle with in tutorials. I probably left them in high ambiguity, much as I’ve always been. Few can stand it and I still don’t know if I served them well enough…to become morally independent of the tottering values of our weak-kneed polity is beyond the strength of any but the most gifted or insane. I am neither but a fringe dweller of both camps.

Listening to Ben and the ASQ playing the piano quintet by Schumann in a very quiet concert hall last Sunday afternoon, I remembered the last time I played it back in 1956. The programme note said S. dedicated it to Clara who was to give its first public performance. But she was sick so had to be replaced at the last minute by Mendelssohn, no less. Schumann died at 46 and the quintet was written 14 years before his death. Karl disliked Schumann and I remember his irritation as I practised the G minor sonata: he said it was ‘nervy’ and he obviously found romanticism unsettling, preferring the order and calm of the Baroque period, starvation rations for me. When I was on tour in Indonesia in ’56, we went to Palembang in Sumatra, and inside the Royal Dutch Shell compound I found an amateur string quartet busting to play the Schumann with me. I wasn’t very good at it but we had such an enthusiastic encounter on a sticky night with constant tuning-up from the strings and sweat pouring off my head as I brushed buzzing insects aside as they whirred about the piano lamp. I remember thinking how incongruous the piece was in that jungle setting – the very peak of nineteenth-century Romanticism pouring its heart out among four cultured European amateurs and one green Australian naif, all variously displaced in the magical tropical night of Sumatra, the strange lush vegetation and alluring scent of cloves and coconut oil. The memories returned in waves as I listened attentively, admiring the group’s poise and Ben’s selfless capacity to blend unobtrusively with them. Not easy with the great black lid up and looming, ‘appassionato’, over the scene: we’ve had such a companionable time together – I always feel rejuvenated after his visits. Yesterday, we had lunch on the river at the Barrack Street jetty Shag Bar Café and afterwards he came home for an hour and played a Prokofiev sonata with great verve and intelligence. I was studying his pedal foot when playing a Chopin waltz and suggested he might be less dry and sparing with it. He was resistant, as I used to be, to the more sustaining grace, the swooping effect the pedal can give – he likes it dry, crisp and austere, putting emotion suspected of falsity at a distance. I put forward memories of Rubinstein playing the same waltz as happily and unhurriedly as if sitting down to a good meal. I think Ben rather despises Rubinstein’s facile hedonism (or that’s what he thinks his music stems from). I once may have armed myself against the same suspect emotion but have obviously softened in old age. Not into mushy sentiment but more able to appreciate the sound of an older man effortlessly enjoying what he did best. So many other things have come to shake me since those days that any respite from the strain of being is welcome.

Today I bought Tears (Naturale) from the chemist, ‘specially formulated to provide soothing relief from the symptoms associated with dry irritated eyes’. Paying for tears which, given the right moment, I can shed for myself. Especially, by strange and touching coincidence, I’m reminded of K. and our younger years as I was by Simon Edhouse’s poignant card and framed photo of Karl in our kitchen in Victoria Ave. Simon had been to Melbourne to help Harry after a kidney operation and, going through some old slides, came upon Karl’s photo. ‘This picture seems so special, and it seemed wrong for us to have it and not you. So I brought it back and had prints made for you and Karl. Warmest regards – Simon.’ Strange, too, that I passed along Bay Road on Tuesday and lingered outside their old house, gentrified with dark green paint and a row of white rose bushes blooming away along the fence line. Further along, the old Practising School and the unbroken avenue of huge eucalypts brought back a rush of memory, the two little blond boys (now 47) running to the entrance in their grey shorts, their little brown legs with knobby knees, and Margaret at home with large tray-loads of fresh cake, the smell of cinnamon, the endless mugs of tea and the intense talk, usually about children and how best to rear them. Talk that often left me troubled, unsure of my direction, even upset to the point of tears, yet always receptive to any possible improvement. I was always self-critical and prone to feeling inadequate so made a susceptible target to self-proclaimed experts. Despite all this, I needed the stimulus of a mind in action since so few of the people I knew at the time were inclined to talk of anything that mattered and there was no shared past with young mothers caught up in the self-denying chores of children’s lives.

So Simon’s kindness and amazing sensitivity caught me unawares and I cried, looking at that young man (he must have been about 37 – the same age as Anna), quiet, slightly amused, kind, gentle, composed, hair awry as usual, unselfconscious and exactly the kind of young man I loved with all my ignorance and inadequacy in full flower. I’ve put the picture on my table and he’s there now, just as I remember him, a very peaceful and beautiful memory brought to me by Margaret’s son in a gesture that wrenched my heart and shook the carefully-built jokey line of defences reared to keep old age at bay. Today, at lunch with L., H. and S., the reality of being 80 came across observing the sad unease of H. and S., one nervous and obsessional, the other static to the point of physical and mental paralysis – a warning greatly heeded. Keep the mind alert, don’t give up, try and be strong for your children and grandchildren. Make the best of this one little life: there’s no other. Enjoy everything you can while you can – it’s terrible to find old friends caving in and giving up. And all this has little or nothing to do with whether one’s husband is alive or dead. We are, finally, alone with all our imperfections on our heads, and this includes memory’s delusions and snares.

Auden’s prescription for novelists reveals his own ambivalence about being a poet. Knowing poets ‘can amaze us like a thunderstorm,/ Or die so young, or live for years alone,’ he negates his own position, having done none of those things and his poetry was never of the thunderstruck kind. He seems to be talking to himself about the need to struggle out of his boyish gift, learn ‘how to be plain and awkward, how to be/ One after whom none think it worth to turn.’ He has to become ‘the whole of boredom, subject to/ Vulgar complaints like Love, among the Just/ Be just, among the Filthy filthy too,/ And in his own weak person, if he can,/ Dully put up with all the wrongs of Man.’ Did he have Proust in mind? Joyce? Certainly not Tolstoy who has never seemed capable of ‘putting up with’ (such an English phrase!) anything that couldn’t be seized by the neck and shaken. What sort of love did Auden have in mind that poets haven’t taken on? Is he implying that the poet’s youthful facility for the graceful lyric denies him a place in his draconian pantheon? It’s really a clever boy’s slant on the morality of writing. What else can ‘just among the Just’ mean other than being fair to all your characters? The God-like omniscient author (G. Eliot?) who practises what she preaches and evokes sympathy wherever possible for the most unlovable e.g. Casaubon. There seems to be some confusion between teller and tale here – whatever she answers, he always sets you thinking. In his ‘Rimbaud’ poem, he goes about the same theme (‘Verse was a special illness of the ear’) from Rimbaud’s point of view but inserts his own moral twist in the last line that gives back to the poet his true function and unappreciated wisdom. Wishing his way into the ‘real’ world, the sphere of practical affairs and lax morality, he dreams of delivering ‘His truth acceptable to lying men’. In the same poem, he wrote contemptuously of Verlaine as ‘his weak and lyric friend’ – it all reminds me of Rakosi’s ‘in an age of injustice, it is embarrassing to be found playing the lute’.

‘You can’t build your own happiness on someone else’s unhappiness’ was something my mother used to say (probably connected with my youthful penchant for older, often married, men). Or their feeling for me – I just went along for the ride, being shy and flatterable and lacking any confidence in myself as female. She was, of course, right but even while knowing it, I didn’t want to acknowledge what I knew. It seemed cowardly and guilt-prone and I’d had a double dose of that as a child. Strange, therefore, that so many of my women friends (all dead now) had a ruthless streak, a foolhardy courage to go against the status quo – I suppose my mother also had it which accounted perhaps for her self-hatred. The one thing I’ve never understood is how D. and M. could leave their children or how H.W.W. could be so cruel to her devoted cavalier servant. Yet, I also noted the irritation and impatience with fond solicitude, a kind of anger with kindness which they equated with dullness, static monotony, as if the ordinary daily chores that keep us alive were too tiresome to be borne. Impatience with earthly life? Desire to shuck off what keeps us earthbound? Icarus-like, they soared in youth but older age proved bitter. I think I’m one of those who prefers the later years with all the pain and disability they’ve brought: the gift of invisibility, the dropping away of self-consciousness, the observer’s vantage point without regret for non-participation. This was a renewed insight during my stay with K. in Gawler when I went to the ‘wrap’ party in Adelaide marking the end of the fifth series of McLeod’s Daughters. I sat outside looking at the flat green manicured lawn of the Adelaide Bowling Club among the red balloons and the clusters of young animated drinkers and talkers and didn’t mind being alone at all. Once, I’d have felt out of gear, wrongly dressed, apprehensive of my role – who, what, where was I? No longer: very comforting and surprising to not even think about such things, and even manage a couple of good talks with two of the directors, R. and S., who didn’t seem to find my company boring despite being someone’s mother.

My favourite subject in science at Junior School was volcanoes, anything to do with grand terror of the explosive kind. Shelley was also addicted to chemistry of the stink-and-bang variety, burned holes in his college room carpet and performed colourful experiments with dangerous chemicals in the graveyard. It must have something to do with poetic vocation (quick burn-out, self-destructive impulse, low tolerance for the dull grind needed for novel writing etc.). Auden seems to have shared the affinity enough to generalise about it: ‘All poets adore explosions, thunderstorms, tornados, conflagrations, ruins, scenes of spectacular carnage. The poetic imagination is not at all a desirable quality in a statesman.’

This is warning enough for me to stop sending letters to the newspaper in one of my frequent bursts of outrage and indignation over hypocrisy and injustice endemic to present government policy, especially the mandatory detention issue. My last letter was unpublished as were the previous two. Poetic ambition and tyranny have been solid bedfellows in some cases: Mao, Hitler, Goebbels, Karadzic. I don’t know where Havel and the last Pope fit in this equation or whether Jimmy Carter’s Always rates a mention in the thunderstorm league. I’m not sure whether Stalin, Castro and Ho Chi Minh should be included as I’ve never seen anything they’ve produced. The thought did surface about French cultural superiority when the new French P.M.’s four volumes of poetry were publicised as an admirable ingredient in his C.V., grandiose adjectives, portentous obscurity etc. M. de Villepin greatly admired Rimbaud of whom he writes that ‘a single verse [by R.] shines like a powder trail [gunpowder?] on a day’s horizon. It sets it ablaze all at once, explodes all limits, draws the eyes to other heavens.’ This was young Rimbaud. What he doesn’t talk about is R.’s wise choice to abandon poetic ambition in his twenties and take up a life of action in Africa without accompanying recitative: gun-running is more lucrative than handling metaphor. Especially at a time of intense liberalism when most people can’t distinguish between actuality and fantasy, the monosyllabic blunt instrument and the imaginative catalyst. Romanticism might serve youth but has to come a cropper eventually. Better not to bring down the world trying to transcend its mundanity so keep out of politics. Or, if you can’t stop writing poetry, keep it to yourself.

In an otherwise unenlightening article on Rembrandt’s late religious portraits, one sentence struck me. It had to do with audience reaction which the writer linked to the discomfort and embarrassment that may shadow huge reputation. Artist as hero becoming Artist as canny entrepreneur (in line with shifting historical attitudes to human behaviour and motivation). He suggests that people who go to see these masterpieces ‘may unconsciously react against their initially awestruck responses. Confronted with works that unsettle ordinary expectations, they may imagine that the safest course is to banalise their own reactions. The public may believe that it is more sophisticated to assume that one is being manipulated than actually allow oneself to be moved’ (Jed Perl, ‘Trembling’, The New Republic 6/6/05). All very hypothetical as it assumes the capacity ‘to be moved’ is already in place. Could it not also be said that being moved exposes one to feelings long kept under wraps for survival’s sake and that safety lies in containing that which might upset precarious emotional equilibrium? This has little or nothing to do with ‘sophisticated’ response. In a sense, one is manipulated by the artist but not with sinister intent. An assessment of audience reaction in a public arena like an art gallery surely has to take account of many more variables than the writer has allowed for: what’s on show is often more than what hangs on a wall, and willingness to be exhibited will vary from one subject to another. Self-analysis or consciousness of reaction is largely beside the point; the desire to appear ‘sophisticated’ is more likely to have figured in Perl’s calculations than in those of whose reactions he claims glib recognition.

Margot L.’s death notice in the paper yesterday set up many memories. Strangely, the day she died I was thinking I should ring her regardless of her reluctance to stay in contact. I knew of her rejection of her Jewish side and unwillingness to be reminded of it. I’m sure this is why she chose never to see me again: just being there was enough to prod past pain into existence. I phone Sally K. who had placed a notice in yesterday’s West, unfortunately misspelled in ‘I shall miss our interesting conservations’. When I phoned, she said she had to arrange the funeral and asked if I would speak. I said no because silence seemed to be Margot’s choice in her severed connection with me and that it would violate what she’d wanted in life. But, if anything might do the job, music would fill the gap. I suggested Bloch’s Kol Nidrei and Sally took up the suggestion with enthusiasm. A time to speak and a time to be silent: words are too treacherous when the subject was as complicated as Margot. I remember one story she wrote about her childhood in Germany and thereafter nothing. The memories of her ruined childhood were clearly more than she could handle and, despite the obvious talent for writing, the material was meant for burial. She was one of the Kindertransport children shipped off to England to be fostered out to several families. Probably a difficult child, she didn’t last long with any of them by her account. Yet there must have been some salvationary moments and they couldn’t all have been as Dickensian as she seemed to remember them. Knowing other orphans and people with what, from the outside, had been terrible childhoods and traumatic experiences, I also recognise that there has to be something in the personality that can, against whatever odds, seize on hope and make a go of life, reach out to friendship and sustain some measure of normality. Within the circumscribed bounds she set for herself, I suppose she didn’t do too badly. But there was a stubborn refusal to probe the truth of her mixed parentage, and, in negating the maternal side, this left her emotionally impoverished. In turn, her friends felt a certain withdrawal, and impossible vacuum which could never be filled no matter what gestures of friendship were available. I feel really sorry I didn’t make more effort in the last years but I didn’t know whether it would be tactful to phone or call since there had been no indication of her wish to revive the contact. I also had a few years out of action and was too taken up with loss of mobility to go further afield than absolutely necessary. It doesn’t stop me feeling bad that I didn’t brush aside all reservations and just bring flowers or a book. Or something to help a lonely old woman (she was 79) cope with her imprisonment and isolation. That War has a lot to answer for as the threads of enforced exile unravel…the genocide of a people and eradication of a culture have left a sad and interminable legacy. Ghostly presences and the muted and often incomprehensible murmur of nearly forgotten voices keep the conversation alive, but soon we’ll all be gone who might have reminded this foolish forgetful world of its moral derelictions. Margot’s life was another link in that iron chain of memory: whether I should have spurred the connection remains an unanswered question. At least, I’m left with what I’ve learned to bear, not always soothing or pleasant but at least proof of a life lived.

I remember being often surprised at the extent of Whitman’s influence and how early it took root. For some reason, I assumed that his being an American would limit the world’s exposure to his work. I wasn’t entirely surprised by Lawrence’s acknowledgement – Walt’s outspokenness fitted L.’s role as outsider-cum-prophet within English society. I was, however, amazed that he spoke to G.M. Hopkins who called him ‘a very great scoundrel’. On the other hand, maybe that great trumpeting voice and loner stance was exactly the kind of companionship Hopkins might well have responded to as a shy, reserved, religious temperament bursting with inner life but out on a limb without a comprehending readership or a Great Friend.

I should have picked Neruda for a fan but forgot his ‘Canto general’ which threw me off the track by his communist sympathy and localised support for Stalin. What he acknowledges is his debt to Whitman as teacher of what and how to see and name in the South American landscape. Like Americans and English before Whitman, everything was familiar in poetry, painting, geography – all named, signed, sealed and delivered to an unquestioning culture. But Neruda saw that there were ‘in our countries rivers which have no names, trees which nobody knows, and birds which nobody has described. It is easier for us to be surrealistic because everything we know is new. Our duty…is to express what is unheard of…He [Whitman] was not only intensely conscious but he was open-eyed! He had tremendous eyes to see everything – he taught us to see things. He was our poet’ (interview, 1966, with Robert Bly). The section of ‘Canto general’ that best reveals Whitman’s influence is ‘The Heights of Macchu Picchu’; in this, poet-as-redeemer (and rather too strenuous in the role) addresses multitudes – ‘Speak through my words and my blood’) you can see Lawrence’s affinity with this.

The Mexican poet Octavio Paz was also an admirer and tried to merge the public and private faces of the poet into one. ‘His mask – the poet of democracy – is something more than a mask: it is his true face…the poetic dream and the historic one coincide in him completely. There is no break between his beliefs and the social reality.’ Paz links this entity with the singularity of America – a bit simplistic as an interpretation, underestimating Whitman’s poetic complexity to which the word ‘democratic’ is hardly applicable: ‘my self’, ‘the real me’, ‘me myself’, ‘my soul’ are just a few of the sometimes irreconcilable personae that flit ironically or otherwise through the action. A lonelier, more remote observer of society couldn’t be imagined. Again, I didn’t know or begin to imagine Borges as an aficionado but discovered that he translated parts of Leaves of Grass in 1969 and went on to distinguish between the author and his mask, Walt and Walter: ‘The latter was chaste, reserved, and somewhat taciturn; the former effusive and orgiastic…it is more important to understand the mere happy vagabond proposed by the verses of Leaves of Grass would have been incapable of writing them.’ Now that is worth telling, especially in this country which likes to envisage its rough-hewn literary heroes as simple livers. Ha! It’s a most necessary antidote to our antiquated scholar-gypsy romanticism inherited unquestioned from nineteenth-century British models. It sits as awkwardly in our fierce landscapes as the rose gardens palely loitering in the sandy wastes of our insubstantial settlements. Home sweet home isn’t anywhere near what the pallid imagination wills. For some, home will always be an idealised mental construct.

Again, Borges said in a 1968 interview that Whitman was the creator of an epic ‘whose protagonist was Walt Whitman – not the Whitman who was writing, but the man he would like to have been.’ Therefore, he becomes ‘an imaginary figure, a utopian figure, who is to some extent a magnification and projection of the writer as well as of the reader.’ Borges speaks of W.’s merging of himself with the reader in order to express his democratic idea that ‘a single protagonist can represent a whole epoch.’ He then goes on to offer two ways of looking at Whitman: ‘there is his civic side – the fact that one is aware of crowds, great cities and America – and there is also an intimate element, though we can’t be sure whether it is genuine or not.’ He likens the character of W. to Don Quixote and Hamlet and this certainly seems convincing enough. There surely are, however, times and poems e.g. ‘Drum Taps’, where public and private faces merge? The gentle compassion of the wound-dresser moving among the dying young men in the Civil War seems a pretty seamless union of personae and evokes more feeling in the reader than the Lincoln elegy which blurs into abstract grandeur on a much larger scale than the more graspably human vignette. Or the live-oak growing alone without company:

…and though the live-oak glistens there in Louisiana, solitary, in a wide

flat space,

Uttering joyous leaves all its life, without a friend, a lover, near,

I know very well I could not.

Yet this is just what he did for all of his poetic life – uttered joyous leaves with or without a friend or lover. He shied away from his strong feelings for young Peter Doyle, and seemed to hang desperately on to a lonely pride rimmed often with self-chastisement, the potential for humiliation always lurking. Fearful of closeness, he rationalised his flight from what he most yearned for:

I hate to have people – throw themselves into my arms – insist on themselves, upon their affection…It is a feeling I can never rid myself of. (Whitman to Horace Traubel, a young friend of his later years)

He also, in line with his intensely personal pitch in his poetry, staged himself theatrically as a brave talkative companion, saying ‘These actor people always make themselves at home with me…I feel close to them – very close – almost like one of their kind.’ No ‘almost’ about it. He was very much of their kind – every theatrical trick in the book but miraculously devoid of thespian ego: a very complicated blend of fastidious recoil and gregarious advance, not unlike that perverse swag of contradictions, D.H.L. himself. It can’t all be laid at the door of unacknowledged homosexuality. There are times when I really wish Freud had never put stuff in my head which I can’t shake myself free of. Would I have thought it for myself without that inescapable grid of character development? Would Shakespeare have pointed the direction as uncle Bloom seems to believe?

Beethoven’s piano in the Bonn Haus on a card sent by S.B. on one of her Handelian pilgrimages (a festival in Göttingen). A warm orange-brown wood, very simple music stand without curlicues, broad-cut wooden floorboards, a cello and two violins in a case at room’s end, two woodcuts of the city and three portraits hanging above a rectangular glass case containing manuscripts and a couple of undecipherable objects. Old Europe and a very familiar angry old ghost. The piano seemed whole enough and in perfect shape but I remember a drawing of him in his workroom in the old Schwarzspanierhaus seated with a quill, an ear trumpet and a smoking pipe on a littered desk. Behind him the battered Graf piano, strings piled askew over the curved edge which he apparently wrecked in desperation to hear his own playing. There are also ‘conversation’ books in which a visitor had to write whatever it was he wanted to say, a broken cup, food scraps and a candlestick. The miracle of the last five quartets when his hearing was almost completely gone stands along with Tolstoy’s 82-year-old break for freedom at the Astopovo railway station and Lear’s rage on the heath as peaks of tragic struggle against our frail corporeality. Somehow, I can’t see a woman rising in old age to such grandeur of defiance, such folly in the face of nature. Too much prudence and self-preservation stops us short of that kind of mad genius. Our madness manifests itself in internal dramas, squalid small-scale breakdowns of the head-in-oven variety. So damn domestic. The one who might have taken on nature in a big way is Emily Brontë but, female enough, she died according to nineteenth-century romantic rules – young and consumptive and indoors. Able, at least, to read her own one novel though somehow I don’t see her doing anything so banal. Thinking of what genius amounts to, at least one of its components has to be titanic energy which can go either towards creation and/or destruction. Whatever it is, the miracle of B.’s last quartets remains unsullied by analysis: unknowable is often the most we can come at. Some would call it God-given but that’s to limit its definition to our impoverished spiritual vocabulary and conceptual arsenal for salvation.

I never warmed to Eliot but he certainly sticks. This morning I’m lying abed, listening to Brahms and worrying about how to position a pronoun in order to ask for a toilet at a service station! Through my raddled brain went old Prufrock’s ‘Sometimes these cogitations still amaze/ The troubled midnight and the noon’s repose.’ (Is that why I titled my last poem ‘Cogito’? No, it was Descartes that set that off.) Anyway, all because of a letter from Ludovic Kennedy who has to be about 80 with bladder to match. It begins, ‘With regard to “toilets”, it depends entirely on whom one is talking to.’ Instantly, I recall problems with ‘who’ and ‘whom’. In Australia, you can’t say the latter with impunity: you’re branded a member of the latte set and relegated to Purgatory for the Élite. After much irritable inner debate, I’d have settled for ‘It depends on who one is talking to’ but I’d feel compromised nonetheless. What about ‘It depends entirely on to whom one is talking’? I was taught never to end a sentence with a preposition. With a name like Ludovic and an Oxford address, he ought to know but maybe he’s trying to achieve street cred by breaking the rules? Aristocracy is always allowed license forbidden lesser mortals. Is there an aristocracy of the aged? Of those who, once having absorbed the rules, are now permitted to give them the finger? By the time I will have sorted this out, it will be too late to find a ‘toilet’ (verboten in upper-class circles at best of times and painful to utter at worst). It’s a form of noblesse oblige to tailor one’s vocabulary to one’s audience but this is the only way. As Kennedy says, ‘To Charles Moore [Spectator editor], I would employ the diminutive “loo” and hope he would reciprocate. But in motorway service stations, for instance, “loo” will lead to bafflement while “toilet” is likely to reap speedy dividends.’

Why, then, does my cogitating tool get to work on ‘reciprocate’ which I always thought implied some sort of mutual exchange or requiting a favour with gratitude? The request for a ‘toilet’ or ‘loo’ between equals is nothing more than the seeking of impersonal relief from an uncomfortable but common problem. Certainly not a warm-hearted exchange of bodily fluids. I’d better get out of bed before cogitation turns amazement into disbelief.

The classical FM station is playing its usual drivelling diet of minor English (Frank Bridge) and Celtic harpies with breathy flutes so it’s Bach for me – Fischer-Dieskau doing the Kreuzstab cantata, as sublime a work as ever was conceived by genius – a solo for F.D.’s wonderful bass, perfect tempo, not too funereal but with an underlying buoyancy as if floating towards death, trusting and ready. The second movement or aria is accompanied by a joyous oboe obbligato solo: ‘At least I shall be relieved of my yoke’, and the final chorale, ‘Come, Death, thou brother of sleep’ seals the whole with an unoppressive tragic resolution. Unlike the fragmentations of Beethoven’s late quartets, Bach isn’t cut off in the same way from the old bourgeois order that informed his life and work. Deepening rather than transcending his perfect balance between this world and whatever might come next, he creates a miracle of synthesis between human and divine. Wholeness sits as naturally and unforcedly with Bach as breakage marks Beethoven. Ripeness is all? Different ways of approaching death. As Adorno said speaking of Beethoven, ‘The maturity of the late works does not resemble the kind one finds in fruit. They are not round but furrowed, even ravaged. Devoid of sweetness, bitter and spiny, they do not surrender themselves to mere delectation.’ Bach isn’t sweet either but, like Dr Johnson, carries weight and the ineffable authority of a man who believes without cant, speaks straight, and has worked all his life in a rigorous discipline that encompasses light and darkness without flinching. This discipline is in itself an act of transcendence. Joy and melancholy are indissolubly bound up in a life that never oversteps into hubris – the music tells as much of mortality as it does of divinity without Promethean presumption. The last cantata, ‘Ich habe genug’ has the most moving oboe accompaniment and has always been my favourite among the many cantatas miraculously written over an astonishingly short space of time (sometimes at the rate of one a week!). He was a dutiful servant of his ecclesiastical masters but, further, of his God. Only when confronted by the miracle of Bach do I yearn to believe. Mozart, almost. Bach, totally.

It comes back to me that I married K. because he whistled Bach perfectly – that was, as I remember, the reason I gave myself and others. It’s as good a basis as any for marriage and I was not disappointed. Staying in the Schaeffers’ upstairs Kamar Tamu for the very first visit to Bandung for a concert, I woke to hear the whistler downstairs, as yet unseen and unknown, and I was enthralled. Every note perfectly pitched, tempo and rhythm exact. I couldn’t wait to learn the whistler’s identity which was only revealed on the last night of my stay when he came for dinner. We were never left alone but he did come upstairs afterwards to say goodnight wearing his dead father’s blue towelling dressing gown. We talked and he recounted briefly and without self-pity the story of his ruined childhood, being orphaned at the age of eight, losing his adoptive father (his uncle) the same year, and being left in Zürich without language, parents, money etc. in the care of his German-born adoptive mother under siege from the stern Swiss clan which distanced themselves from all foreigners. I knew I would marry him. I would make it all up to him. I would make it better. It wasn’t a question of pity: it was admiration, respect, and a genuine love for someone who had come from the fire so seemingly independent, so untouched by falsity, so intelligently balanced and content with his lot, modest and without the egotistical thrust that set me at odds with most of the young men I’d known up till then. I’d always admired quiet scholarly old and young men, feeling inferior to them in every way but wishing to be of their kind. Passionately idealistic, ignorant, I must have been rather like Dorothea Brooke whose limited puritanical upbringing (I didn’t think mine had been so at the time) ‘turned all her small allowance of knowledge into principles’. Hardly equipped to deal with the surreal confusing world of post-revolutionary Indonesia with its remnants of Dutch colonial society, its rootless émigrés from war-torn Europe both innocent and less so (Vlaschutz from Montenegro, the German doctors in central Java who took Karl in after his motorbike accident and kept him in their home for 6 weeks, deeply concussed and without the medical treatment that today would probably have detected whatever damage he’d incurred). He never could remember anything about the accident. Only the recreated detail by observers told him he must have clipped the hub of an ox-cart and was tossed in the air to fall unconscious on the road. The context, the landscape, the people were so alien to me, so attractive sensuously and spiritually that I had no defences against this luxuriant feast nor my freedom to choose unreservedly, and without parents to put the damper on life.

Here is George Eliot on Casaubon: ‘Consider that his was a mind which shrank from pity: have you ever watched in such a mind the effect of a suspicion that what is pressing it as a grief may be really a source of contentment, either actual or future, to the begin who already offends by pitying? Besides, he knew little of Dorothea’s sensations…’ That’s a knotty one, but I long ago realised my offence and regretted my blindness: I was as much unloved as he which made us powerless to comfort each other as we wished to do when, in more difficult times many years ahead, survival and sanity were at stake. What an irony that the very qualities I admired so much in the young man in Bandung in 1957 (‘freedom to choose unreservedly and without parents to put the damper on life’) were actually my own but not recognised until many years later. Acknowledged now as mine but with sadness and regret – not as desirable attributes but as delusions of independence which fooled me thoroughly. Both of us. So much for Pelagian free will.