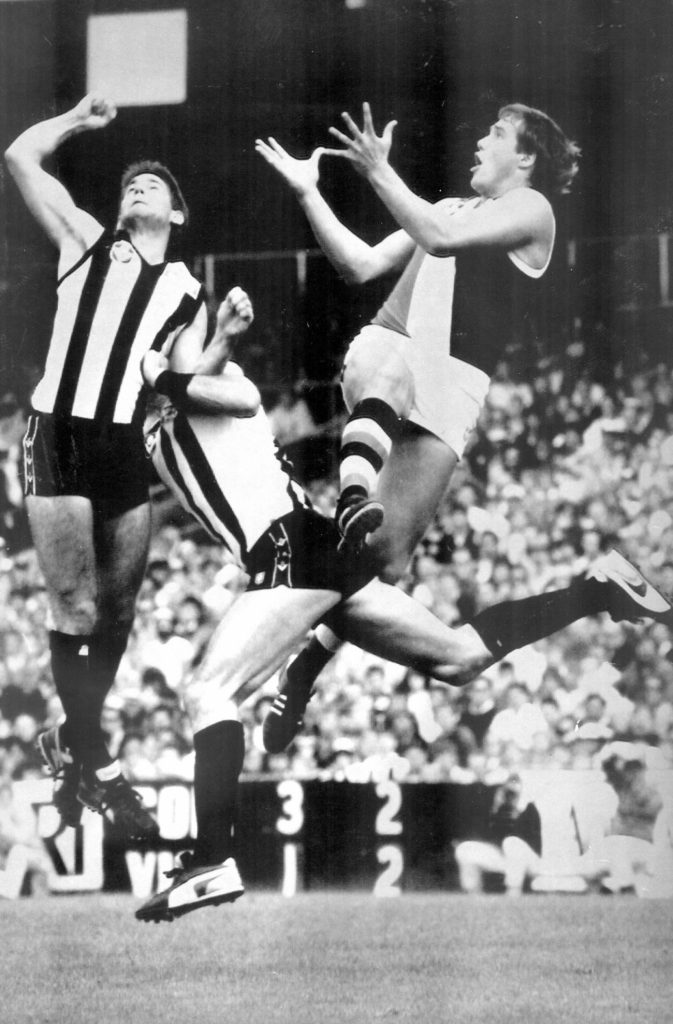

Tony Lockett in the Eighties

When the Sydney Swans met the Hawthorn Football Club at the Sydney Cricket Ground in May last year, the game was a strange kind of anti-football: topsy-turvy, through the looking glass. And we have become so used to it no one noticed. Here was a game of Australian Rules football played on a warm Sydney Sunday in bright sunshine, far from Melbourne mud. Hawthorn, not that long ago one of the greatest sides in the game’s history, came in as rank underdogs while Sydney, lately one of the worst sides, was looking at top place on the ladder. And the big interest focused not on this or that dashing new recruit, but on the two old crocks hobbling around at either end of the ground. In the full-forward positions were Tony Lockett and Jason Dunstall, both ancient in football terms with around five hundred punishing games between them. Dunstall barely makes it on to the training track these days, and took the field with more protection around his knees than a champion rollerblader. Lockett looks outwardly fitter, but has been so surgically sculpted that no one knows what might go next. In the previous game, he had been blanketed, getting a single kick for a single goal.

They ought to be the game’s has-beens, but no one dares write them off. With his fourth goal of the game, Lockett kicked the twelve-hundredth of his career. This would seem a strange number to celebrate if it weren’t that the all-time record is Gordon Coventry’s one thousand two hundred and ninety-nine goals, and that the only other man to have passed twelve hundred was Dunstall, at the other end of the ground. Physiology would suggest that the two gun forwards will not line up opposite one another again; in any case these full-forward ‘shoot-outs’, as they are billed, are usually anti-climaxes. This one wasn’t: soon after the last break, the unfancied Hawks led; Dunstall had four goals, Lockett five. Then the Swans clicked into a higher gear. Suddenly the ball was being delivered to Lockett from everywhere and he kicked Hawthorn out of the game with six goals for the quarter.

St Kilda supporters like myself have to grimace and pretend to assume a purely aesthetic interest in the game when this happens. The last time I saw Lockett kick eleven goals at the SCG was in 1994 when he was still wearing the red, white and black of St Kilda. With his last goal he brought off an astonishing win against Sydney after the Saints had been down and out, adrift by forty-eight points several minutes into the final quarter.

Most of my time with Tony Lockett was spent on the weed-choked terraces of Moorabbin, St Kilda’s old home. The slightly grumbling folklore was that most of the play went on in front of the stand, because that was where the roar for the home side was greatest. The effect opposite on the terraces was often stupendous. It was not a huge ground, but an average crowd in the stand produced the atmosphere of sixty thousand at the MCG. A Winmar gather on the wing would start it off; we on the terrace would squint into the shadows and maybe catch Winmar’s run against the motley background before he spotted the lead. A moment’s lull, time to flick the eyes to the leading Lockett, then the shockwave would hit us even before we knew that Lockett had come to ground with the ball or simply got out in front and taken it again. At the southern goals, we never needed to wait for the goal umpire’s signal; ten thousand voices told us truly enough how the kick had gone. I remember the miracle of a rare Lockett torpedo punt. He had marked somewhere in the shadow of the stand and must have judged he was too far out for the drop punt. I never saw the kick, just the ball wobbling in an arc so huge it seemed beyond reference to anything as insignificant as the goalposts. But the roar when it came was huge, and it was truthful.

Still people ask me why I would want to write about Tony Lockett. ‘Isn’t he a thug?’ they say. In Sydney, no one forgets the day at the SCG in 1994 when Lockett clashed early with Swans defender Peter Caven, whose nose was smashed on Lockett’s elbow. Lockett received an eight-week suspension. One day at Moorabbin I saw him kick fifteen goals (as it happened, against the Swans), but spend so much time wrestling with opposition defenders that we wondered whether the Tribunal would let us see him again that season. In any case, Lockett has not been a Saint for more than three years. Now he’s the highest-profile Australian Rules footballer in New South Wales, his career winding down. He kicked more than a hundred goals in each of his first two years with the Swans, and in the second year put them into the finals. He broke the hearts of St Kilda supporters, myself among them, when he left at the end of 1994. And these are hearts well-credentialled in the breaking business.

The answer is simple. Lockett’s job for almost the entirety of the two hundred and fifty-odd games he has played, barring a few minutes in the ruck here and there, has been the straightforward one of getting the ball and putting it through the goals, ideally through a mark and resultant kick or, if necessary, the harder way in general play. Simple, and incredibly difficult all at once, with opposition backmen doing everything they can, legal and illegal, to stop him; with ruckmen dropping back to get in the way; the supply of the ball, for at least half of those games, coming from a very weak team. And with the media scrutinising every action, on- and off-field.

There is a lot that suggests that nobody has ever fulfilled this task better than Tony Lockett has. In raw figures (which never quite tell it all), only one man has kicked more goals than Lockett and he seems likely to pass that mark in 1999 and to do so in considerably fewer games than the current record-holder. But sheer weight of numbers is only half the story. Lockett had kicked around nine hundred of his goals for the Saints by the time he sealed a narrow win over Collingwood in his last St Kilda game at the end of ’94. He conjured up improbable wins, gave hope in appalling losses. I saw very many of these games and goals. I am rather less interested in the three hundred and fifty goals he has kicked since then for the Sydney Swans. This is not simply about the dispassionate admiration of skill but about someone who made one of the worst Australian Rules teams of recent times a joy to watch.

Neither is it about pure pleasure, not at all. I don’t pretend that Tony Lockett hasn’t made my life difficult. When he kicked ten or more goals to deliver yet another unlikely win to St Kilda, it could provide a sustaining glow for a week, Tribunal willing, but on balance I am sure there has been more despondency over the years. And it has not always been possible to enjoy the wins fully, or the double-figure goal hauls, for worrying about Tony Lockett’s groin, or knee, or back, or upcoming Tribunal appearance, or rumours of imminent moves to Carlton, Collingwood, or the Sydney Swans. My relationship with Tony Lockett has not been like a relationship with a girlfriend or wife. It has been much more difficult than that. You can patch things up with your partner, or walk out; you reach understanding, or you call it off. In the end, I don’t think I fully understand Tony Lockett.

After years of playing with our feelings, Lockett left St Kilda at the end of 1994. The rumours that he wanted to go from St Kilda had been intensifying for weeks. There had been rumours before, and I tried to ignore them. For a time it was to be Collingwood that would take him in, then the Brisbane Bears, then the Swans. The newspapers, including the usually reliable Melbourne Age, announced a move as imminent. But the papers, in their eagerness for a scoop, are often wrong about player movements and I didn’t give up until I heard Lockett’s manager, Robert Hession, speaking on the radio news, saying it was over. I was listening to Classic FM on the ABC at the time, and I had never heard anyone on that station refer to Tony Lockett before. In fact, I had never heard anyone refer to football on Classic FM (this was back before it was devoted to classical greatest hits, middling celebrities talking about classical greatest hits, and the mating calls of frogs). So I knew it was true.

You realise at such times that however much you love following one player, you don’t really have an allegiance to that player alone, even when he is a colossus. Somehow, he is not that same player when he puts on another jumper. Perhaps it is possible in English football when your hero goes to another stage: from Premier League to the Italian Serie A, for example. But here in Australia when your hero moves he goes to a rival club (one which, quite possibly, you already loathed before it stole your player). It is even worse when the new club starts doing well and, needless to say, worst of all when it does well against your club.

So I find myself dwelling on Lockett in the 1980s, not just because that was when I lived in Melbourne and saw him most, but because already he has become sedimented in legend. It suits me better to see in memory the figure with the awful larrikin haircut (cropped at the front, long at the back) than today’s crew-cut version. These days, there’s a touch of the aged Beowulf stepping out to meet the dragon about him – it could all be over very soon. It’s easy to adopt a sagely mythologising attitude: sure he’s good now, but you should have seen him against Grendel.

Lockett began playing for St Kilda close to the club’s lowest ebb, in 1983, when the side would comfortably take out the wooden spoon and hold it uncontested for the next three seasons. He appeared in twelve games that year, kicking nineteen goals while Mark Jackson clowned it up in the goal square and made sure no other forward interfered with his space. The hapless Saints had been able to secure their big recruit through the old zoning system. Lockett’s talents were hardly a secret; he had dominated in North Ballarat as a teenager, and his father had been a famously talented bush footballer who never made the move to the city.

Nevertheless, when he took up full-time occupancy of the goal square at St Kilda in 1984, Lockett’s results were for a time solid rather than spectacular: seventy-seven goals from twenty games in that year, seventy-nine from twenty-one the year following, and in 1986, sixty goals from eighteen games. The kind of contribution you would rather have than not, but not the stuff of legend. There were excuses, mostly in the form of injuries. When he was on song, nobody stopped him. And that, given that he was looking for delivery of the ball from the worst team in the league, was a considerable achievement. Without ever having kicked a hundred goals in a season, or a double-figure total in a game, Lockett was already the most worshipped Saint at the beginning of the 1987 season.

There was a sense that something had to happen at St Kilda. The club had almost gone bankrupt the year before. Darrel Baldock, club captain in the glory days of the 1960s, had been brought back as coach, perhaps less for his tactical brilliance than as an icon of former success. The side responded by losing in the first round at home by a point to Geelong. A win was notched up in round three, Lockett’s contribution just ten goals to this point. But that Easter, St Kilda met Melbourne – eventual grand finalists – on the Saturday. The Saints lost, but Lockett kicked twelve of the side’s fourteen goals to take the club record for goal-kicking, equal record for goals on the MCG, and the most anyone had ever kicked in a losing side. Something interesting was going on at St Kilda.

I have often thought about this game, and the times I have seen Lockett kick a swag of goals even while St Kilda lost. By this time, Lockett’s career coincided with that of Jason Dunstall. Dunstall was a very different kind of player, less demonstrative than Lockett but equally devastating. He would have been good in any team, but he played in a Hawthorn side that at the time was usually the best. A less charismatic figure (and playing for a team that knew how to handle the media), Dunstall was the good twin to Lockett’s evil genius, a simple polarity which suited many of those who had to write about them.

It is staggering that Lockett did what he did in one of the league’s worst teams. No one had ever kicked twelve goals and seen their side lose before, but that is what happened against Melbourne. In 1987, he at last delivered; consistent, after the twelve-goal haul, Lockett played in every game and finished the season kicking eight, nine, eight, eight, three, eight, and five. Even a bad side couldn’t help winning a few with somebody contributing like this, and the Saints did beat several teams on their way to finishing tenth. Lockett kicked 117.52, and went on to share the Brownlow Medal with John Platten as the first full forward to win the medal.

Some years ago, I managed to get in to a performance of Hamlet at the Barbican in London with Kenneth Branaugh playing the lead role, in a return to the RSC after many years. It is even more fashionable in Britain than it is here to criticise Branaugh, who is surely amongst the celebrities the British most love to hate. This performance was quite unlike his populist and sometimes very middle-brow Shakespearean films. Hamlet was performed full-length, and Branaugh’s was at least a twelve-goal performance. Reflecting on it later, back in Australia, I realised that I would probably never see Branaugh take on Hamlet again, but that I might see him move into the older roles, one day, perhaps, to do Lear.

That doesn’t happen in sport. There is no Lear on the football field. So there comes a point with someone like Lockett when you realise that something special is happening and you had better get along to see it, and see as much as possible. Football heroes are Homeric: exaggerated, larger than life, and soon gone. At worst, our heroes come back as those gibbering shades, the commentators.

1987 was perhaps Tony Lockett’s Hamlet. Looking back, it is a slight surprise to see that the twelve goals against Melbourne was the only time he reached double figures that season. But he played every game, and kicked straight, and shone in a side that would certainly have contested the wooden spoon if he had not been there. So we expected everything in 1988; a finals appearance, no less; Hamlet without the tragedy, perhaps. But Lockett would always struggle to play a full season. Up until then, his niggling injuries had cost him a week or two here and there. He had had a two-week suspension in 1986 for striking Footscray’s Rick Kennedy. It is not much remembered that at the beginning of the Brownlow year, Lockett was reported for striking one of his own teammates, David Wittey, who was (allegedly) thumped in an intra-club match. Trevor Barker would later recall that Lockett treated his teammates in such practice games much as he would any opposition player. One of the time-honoured defences – ’he doesn’t know his own strength’ – would often be invoked after yet another defender was felled. This was a side of Lockett not seen in the Hamlet year; 1987 was all nobility. Lockett has topped all his own records since then, but everything he has done has been accompanied by big doses of tragic flaw, at least in the eyes of those paid to write about him.

The St Kilda Football Club had turned up a true star, and didn’t know what to do. Unwisely (as hindsight clearly shows), the club closely watched its star and shielded him from media contact. Lockett, in turn, obviously disliked the city, and remained based in Ballarat in his early years at St Kilda, which would become the source of much tension between the club, its star, and the rapacious print media. At the Brownlow dinner in 1987, we saw a public Lockett not glimpsed before: as the count grew tighter towards the end, the big man sat with fingers on both hands crossed, eyes screwed shut. He was unashamedly tense, and equally without self-consciousness embraced his girlfriend when the votes were announced, and he clinched the shared award. A big country kid? Perhaps, but it was hard not to share the sheer spontaneous pleasure of the man in the moment. Later, it would become clearer that the same spontaneity and lack of self-consciousness marked his entire controversial career.

The kind of scrutiny and pressure the Brownlow win and the hundred-goal season brought to a player who was only twenty-one was not dealt with effectively either by player or, more importantly, club. There are ready-made mythologies in sports-writing for this sort of player: Lockett would be, for a time, the ‘reclusive’, ‘shy country kid’, on the basis of not much more than the negative evidence that he didn’t say a lot, and wasn’t around much to say anything anyway. Newspaper writers, by contrast, felt they had to say a lot about him, and they could hardly be blamed for that. St Kilda – a club more used to media scrutiny of its financial mismanagement than its brilliant football – felt he was best off protected from exposure. As Jack Dyer and Brian Hansen point out, this was a fatal mix. It was naive of the people running the club to imagine that an emerging superstar would be left alone by the media, and not to realise that if they didn’t give the media something to print or film, they would simply encourage speculation and, at times, outright invention.

1988 gave us the other side of the Lockett career, the other side of being an instant hero and having no idea how to deal with it. It was a tale simply told. In round one, St Kilda lost badly, the reigning Brownlow medallist kicked four, knocked out an opposition defender, and received three weeks on the sidelines from the Tribunal. The Saints went on to lose a string of games, though Lockett hit form with seven, seven, and nine (in a losing score) up until round eleven. Then disaster. Against Footscray, VFL Park, he lead out and came down heavily. I can still see the trainer dispensing clouds of ‘magic spray’ at Lockett’s ankle. He was clearly in agony, and this was just one of many ludicrous insensitivities practiced by the club. It would turn out that he had a broken ankle which would require the insertion of a plate. But the trainer, in his desperation to keep the star out there, let off enough of the freezing spray to put a rover into cryogenic suspension. It was the end of Lockett’s season: 35.19 from eight games. The Saints won just one more game, four in all for the season, and finished bottom. Meanwhile, the good twin Dunstall kicked one hundred and thirty-two goals and came equal second in the Brownlow count.

A few days after the injury, Lockett was besieged by cameras on arriving at hospital on crutches. He tried to limp away from the waiting journalists, but instead slipped on a mat and fell flat to the floor. That was when he got up, took his crutches like javelins and speared them at the cameramen, knocking one over. This went straight to the evening news bulletins. Much later, Lockett made some standard remarks about the incident in his autobiography: ‘I look back on it now and laugh, but at the time I was furious’; ‘If it happened to me now, I’d handle it a bit differently – probably count to ten and then throw them.’ But he also made the more telling point that one of the things that got to him was that he couldn’t understand how the media knew about the hospital appointment. ‘Noone was supposed to know except the club and me.’ Of course it didn’t have to be someone from the club who spilled the information, as Lockett implies; it could have been someone at the hospital. But this kind of thing was typical of St Kilda in those days, and it was the first serious instance in which a possible leak from the club would create tension between it and Lockett.

He was back in 1989, apparently fit, the biggest star in a troubled club and amongst the most-scrutinised players in the league. In the opening round at Moorabbin, St Kilda beat Brisbane, then a nothing side, and Lockett kicked nine. Next, he sealed a four-point win with his tenth goal in the last minute of play against Carlton. Then he kicked eight in a loss away from home, the Saints fragile as ever away from Moorabbin. And then one of the toughest fixtures of them all, Victoria Park and the hated Collingwood crowd. St Kilda had not won there in years and years but Lockett’s form, despite the round-three hiccup, brought a new optimism. Here was the real VFL: the tiny ground wedged in amongst the terrace houses of Abbotsford; Collingwood fans tearing down a piece of corrugated iron to make their own way into the ground; dirty-bricked factories visible from inside. No terraces behind the goal here, more a mudheap, with netting behind the goals – to stop the ’Pies fans stealing the ball, so it was said.

The Saints were down by seven goals at half time, but the mad optimism I took along in those days made it seem not insurmountable. Lockett had barely seen the ball, and at one stage was moved from the goal square, provoking jeers from the Collingwood crowd. He still kicked five – which as it happens is exactly what he has always said he tries to kick, every game. The Magpies kicked goals at will in the second half, to finish with 23.21, and a better-than-ten-goal thrashing.

It got no easier from there: a solid beating at Windy Hill – more of the bloody real VFL – five to Lockett. He kicked six the following week in a win over Sydney at Moorabbin. Then there was the trip to Geelong. The Cats kicked eleven in the third quarter, and nineteen in the second half, to finish with a monstrous 35.18 and a twenty-goal win. Well, it was their Hamlet year, filled with such astonishing highs as this, before the tragedy of the six-point Grand Final loss to Hawthorn.

Tony Lockett, to this point, had kicked forty-nine goals in seven games. He seemed unstoppable in a side that apparently could not win away from Moorabbin, and which, in two of those games, was beaten by twenty and ten goals. The league goal-kicking record – one hundred and fifty goals in a season held jointly by Bob Pratt and Peter Hudson – was now thought to be under threat. He kicked nine the following week, and went ahead of what was needed for the record. Then he took the field against the West Coast Eagles in the mud of Moorabbin.

Every time I see Guy McKenna, who has since developed into a top defender, I think of it. I see Lockett take the mark, then I see McKenna hanging on to him, just that little bit too long. And I see Lockett do that shrug, that flick back with the elbow. He is magnified in memory; he is the good-hearted monster in the horror movie, whose own misunderstanding of his strength causes tragedy. McKenna went straight to ground, concussed. Rather lamely, the club would later suggest that he had been knocked out not by Lockett, but when he hit the ground. He was carried off on a stretcher.

Lockett was reported, but went on to kick twelve in a comfortable win. But here was a new feeling; a kind of roiling low in the gut. It was impossible to enjoy the twelve-goal haul. The Tribunal handed out four weeks.

To that point, Lockett had seventy goals in nine games – one ahead of Pratt, the record-setter in 1934. Rage at the Tribunal seemed more complicated than simple frustration at the removal of our best player. Couldn’t they see that history was more important? Couldn’t they see they didn’t have the right to take away attempts at records from us? The following week, at freezing cold Waverley, the Saints won without their star, but they then embarked on a ten-match losing streak. Lockett came back after suspension to kick eight in two of these losing games. But all the momentum was gone; a groin injury, apparently incurred during a State of Origin game in which he had kicked five goals, set in. As ever with a Lockett injury, nobody seemed to know what was going on. Some weeks he would actually make the team list in The Age, but he did not play again after round sixteen. He still came third in the goalkicking with his seventy-eight goals, but Dunstall kicked one hundred and thirty-eight.

Behind the scenes, nothing was going right. While Lockett was not actually out on the field kicking huge swags of goals, the ‘troubled genius’ story was being mingled with the ‘shy country kid’ narrative to produce a bad boy. After the game against Sydney, for example, Lockett was involved in an ‘incident’ at the St Kilda club disco, in which, apparently, he knocked over club manager Ricky Watt. According to Lockett, Watt was nothing to do with the dispute, which centred, significantly, on someone telling the player he should have kicked more goals. (He had kicked six, in a winning score.) Lockett was without a driving licence at the time because of speeding offences, and went home to Ballarat with a friend. The friend put the car in a ditch (early newspaper reports suggested Lockett had been driving), and they did not get home until five-thirty in the morning. Training for the State of Origin game was at eight back in Melbourne, and Lockett missed it.

He eventually played in the State game, with distinction, alongside Jason Dunstall for the first and last time in a demolition of South Australia at the MCG. This was the ‘good’ Tony Lockett, as if some Dunstall had rubbed off on him. He only got there after a great deal of publicity over his bad side. Was he really committed to the Big V? Should he be allowed to take his place after missing training? Was he fit? Lockett was fined; there was talk of his being suspended from the next Saints game for missing State training – an idea which probably would have started a riot had it been followed through.

For most of his remaining time at St Kilda, Lockett would be the object of adulation from the terraces, and incessant questioning from many in the media. Is St Kilda a one-man side? (Too ‘Lockett-conscious,’ as they would say on Channel 7.) Would the Saints play better without such a dominant player in the square? Did his various misdemeanours mean that on balance the club would be better off without him? All these questions are part of that glorious confusion that is sports writing. The emphatic and in a way obvious answer is no. Would any sporting code be better off without an individual who happens to be extremely good at it? Would the fifteen hundred metres be better off without very fast men and women, or the high jump better off without people who jump extremely high in the air? If they stay on the right side of certain shakily consensual boundaries – avoiding performance-enhancing drugs, for example, and not, as an American basketballer did not so long ago, threatening to kill an umpire – then it is hard to see how the sport could be better off without those who are very good at it. If, however, they transgress certain other boundaries – by abusing rackets or umpires, by failing to turn up for State training – then they are only falling short of standards of gentility. Much as we would like them to be as graceful off the field as on it, we have to be content with them. Agamemnon would have had an easier time on the parade ground in front of Troy if he’d rubbed out Achilles for making himself unavailable. But the Iliad would have read like yesterday’s news in hexameters.

After 1987 and the Brownlow, then, the tragic flaw, the intemperateness. Lockett could not, in a way, be in the right again, except for the adoring crowds. In the eyes of those who relentlessly ran him down, such as the Melbourne journalist Mike Sheahan, he was a thug, a liability. Why not run him down? It was a prosperous little quasi-controversial industry, and such writers as Sheahan could mill out metres of copy from it. This was the ‘such a talent, pity about the personality’ narrative. On the other hand, Lockett’s supporters had him anointed as successor to the big goal-kicking legends, Bob Pratt and Peter Hudson, and likely taker of the one hundred and fifty-goal record.

Lockett himself never responded to this pre-set narrative laid out for him, and was even more contemptuous when, later, it was suggested he could kick two hundred goals in a season. In fact, he said so little about anything, and has disclaimed interest in personal records so often, that he has become something of a football tabula rasa, which scribes are all too eager to scrawl on. At an early stage, the key theme in writing about Lockett became what he could do – especially if he had been someone else. Increasingly, what he might achieve was defined without reference to anything he was actually doing. Meanwhile, Lockett himself kept maintaining that what he tried to do was kick five goals a game, with anything else a bonus, and thereby help his club to a premiership. But everyone, always, wanted more. In 1990, he opened the season by kicking ten and nine. The headline in The Age read, ‘What Will He Do When Fit?’

When Lockett moved to Sydney the Swans were the bottom side, ridiculed in their adoptive home town, and still struggling to escape the embarrassing association with the failed razzamatazz of medical entrepreneur Geoffrey Edelsten’s ownership. A perfect place to get paid well in his last years – and remain distant from the attentions of media and fans. Lockett was, for a time, almost anonymous in his new town. And if he had kicked a solid sixty or seventy goals a year, he might have stayed that way. Instead, he helped the Swans off the bottom of the ladder in 1995 with one hundred and ten goals and took them into a grand final the following year, topping the goal-kicking with one hundred and twenty-one. Then he got into trouble again over some allegations about sharp practices with his greyhound-breeding business and he was all over the papers in the off-season as well, until the charges were very quietly dropped.

In 1998, Lockett commenced what will be one of his last seasons very slowly, looking awkward at times and reduced to the level of a mere mortal. Just as the vulture scribes began circling round, he kicked seven in Perth in a win over West Coast, and more recently, the emphatic eleven to beat Hawthorn. It was his twenty-first bag of ten or more goals, extending the record for such feats, which he already held. We won’t see the one hundred and fifty goals beaten now, not by Lockett or Dunstall. Gordon Coventry’s all-time goal-kicking record of twelve hundred and ninety-nine is well within reach, Fred Fanning’s game-high of eighteen probably too much to ask. None of it is the same for me. I’m watching one of the greatest full forwards ever, of course, but emotionally, Tony and I have gone our separate ways. If Lockett did get to thirteen hundred first, or kicked eighteen goals, it couldn’t mean what it might have for to me, once.

Still, I hope I’m there if it happens.

Bibliographical Note

“All this, I am aware, sounds fanciful and is perhaps misremembered, written up. But if it is: well, that is the spectator’s fate—we watch but in the end we have to guess.” (Ian Hamilton, Gazza Italia)

Memory was aided in the writing of this piece by: Jack Dyer and Brian Hansen, Captain Blood’s Wild Men II (Mount Waverley: Brian Hansen Publications, 1994); Jules Feldmann and Russell Holmesby, The Point of It All: The Story of St Kilda Football Club (Playright Publishing, 1992); Tony Lockett (with Ken Piesse), Plugger: The Tony Lockett Story (Sydney: Pan Macmillan, 1992); Stephen Rodgers and Ashley Browne, Every Game Ever Played, 6th ed. (Ringwood: Viking, 1998). It is also influenced, in many important ways, by Nick Hornby’s Fever Pitch (London: Victor Gollancz, 1992) and Ian Hamilton’s Gazza Italia (London: Granta Books, 1994). The quotation from the latter is on page 12. Special thanks to Clare Forster, Brian Matthews, Jeff Richardson, and Imre Salusinszky.