The Last Local Heroes

(Kalinga, Northern Philippines)

For Belen and Sam Saguindel

1

She says she remembers only being young and unmarried at the time. When you are young and unmarried, men like to look at you, since a young girl with tattoos is lovely to see when she dances. At a feast or wedding she opens her arms as an eagle, blue and white beads on her forehead, gold in her ears, strings of yellow stone, green glass and white clam shell across shoulder and breast like a bandolier. Her palms turn upward as she leads the village. Her eyes are shut. But the eyes of all the men and even the women follow the tattoos on her arms, shoulders, breasts, as if they are watching her in the sky.

The tattooist was from Lubo, maybe eight hours walk from here, and his name was, perhaps, Inaw. Her mother picked out the designs: the fern leaf – lafat – and tiny triangles that reproduce the skirts women fold. And even though the family paid him with a pig, her mother also butchered a chicken for him and made a meal of sticky rice: it was a celebration, her daughter was her pride.

It happened the usual way. Inaw found thorns from the pomelo tree, straight, sharp thorns, half as long as his thumb. He bound one at right angles to a short stick, his wand. The girl lay still, lulled by her mother’s whispers. In a coconut shell he carried, Inaw mixed black ash with water into an ink and this he dabbed and rubbed into the small bleeding circles, lines and waves that, with a hammer, he tapped out of her skin. Two days it would take to finish and she could not touch her skin for five days more because of the pain. But the girl was slight and young and pretty and in shock, so Inaw advised her mother to keep her at rest for ten days in all.

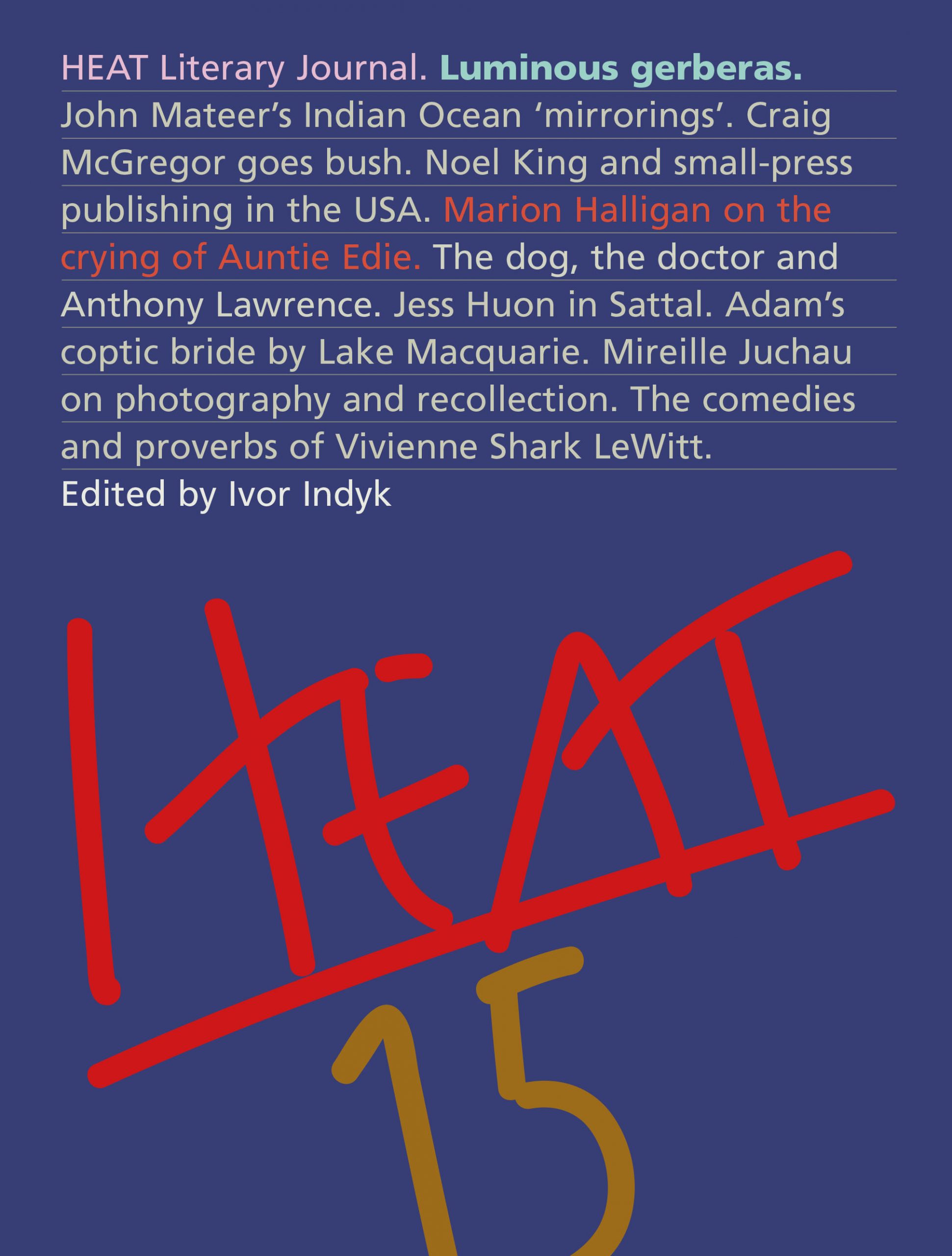

Once she became a married woman, moved away to her husband’s country and had children, she was given other tattoos, but she does not speak of these. The strings of centipedes – kinayakaya – on her shoulders and here, she says, around her neck, are not from this place. They are special designs, different from what you see in this village, among these people. She rolls the sleeves of the tee-shirt down again to cover them. She stretches the shirtfront to display a cartoon – a girl in local dress, who smiles beside a slogan: ‘I AM AN ACTIVE Community Volunteer Health Worker of Tinglayan village.’ These designs, she says, are what she shows nowadays.

2

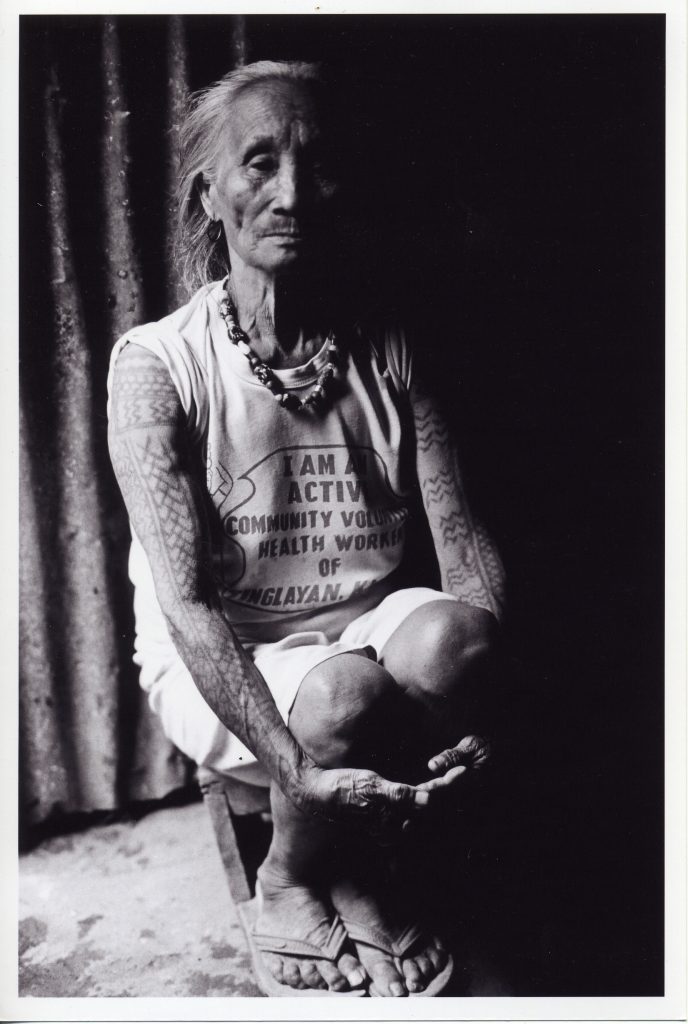

She remembers getting the tattoo when she was a girl, when the Japanese were in Kalinga. She thinks the man who tattooed her was from Tulgao, across the valley, and maybe his name was Teyater. He may still be there, though exceedingly old, if so, for he was already an old man when he came. She picked out the designs herself, which surprised her mother and amused the tattooist: it showed the woman making her way out of the little girl.

Each arm took one day to be done. She had to stop many times, held down by her mother, especially when the needles hit the bones close to her wrist, but she knew the pain would eventually pass. In ten days there would be no more fever and by then her mother could run a hand over her skin on either arm and she would not faint, or flinch. She is smoking now, a cigar she’s rolled thickens the room. Between puffs, she lets her hands hang, displaying the decorated underside of her wrists like bracelets, the pattern of the freshwater crab – akama – running up her arms until it becomes the magnified pattern of akit, the bitter fruit of the rattan tree, tessellated like snakeskin.

When people die, she says, they take their tattoos with them to the next life. You cannot take your clothes, your pigs, your fields, your riches to heaven, or your husband – mine is dead. But your tattoos go with you forever. The dead, you see, if they are dug up, still have beautiful tattoos. This is because the needles go through the skin and bone, straight to the soul.

3

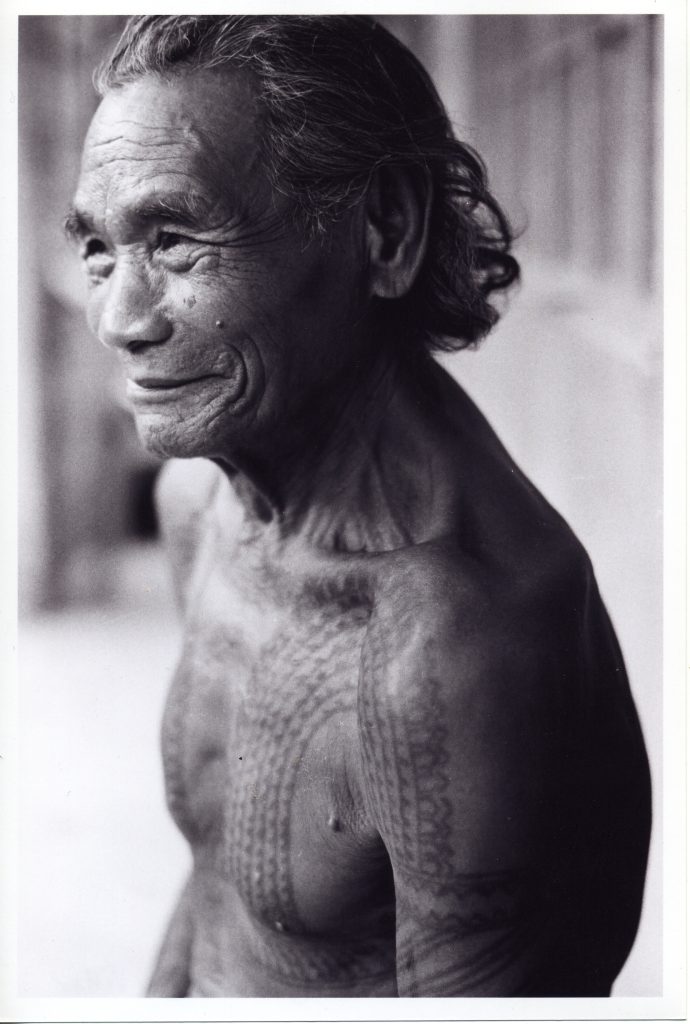

He remembers a time when the men from Lubo, beyond the town of Sauyang, to avenge a half-forgotten wrong, had planned tribal war against his place, Tulgao, high above the Chico river. A dozen boys, none older than seven, are sitting around him, not yet listening as he speaks.

The elders of Lubo, themselves old warriors, consulted the natural world for signs of whether their plans were auspicious, for nature reveals the future to those who can see in her movements the fortunes of men, the cycles of birth, harvest and death. Far away from their village, the old men were given the first sign: Idao, the great bird of these mountains, came to rest on a branch and began a long, shrill call, the sigod song, that foretells resounding victory. They waited for six further omens. When at last they heard the great bird chirp while it made a jagged path across the sky, they rejoiced, for fate had given the final sign, a confirmation that their assault would be favourable in all ways, without great casualty, without difficulty.

Marching to the Chico River, the men from Lubo sent messengers to Tulgao with a challenge to accept the war which rumour had already announced weeks before and fight at the riverbank. Such war was kayaw, war without surprise, open to every village male, grown men and awestruck boys both. To refuse was to be laughed at. By then, rumour also reached soldiers of the Fourth District constabulary, who arrived to stop the conflict and for the benefit of official records, reported and dated it to March 1940. But before the troops intervened, the Tulgao men fought bravely, fought like their fathers before them, with spear and shield and head-axe. They took three lives. The men of Lubo took four because they had an advantage. It was not bravery. It was a rifle.

He had killed one of the three warriors with a spear and was responsible for what followed; he cleaved the head off its body with a head-axe, dislocated the jawbone as custom dictated and took it back to his village where it was made into a handle for a gangsa, a ceremonial brass gong. Men from Lubo asked for bamboo poles to carry away their dead and make litters for their wounded; Tulgao men obeyed the pieties of honour, so no one disturbed them. Silently while they are listening, one or two of the boys take make-believe axes to each other’s throats.

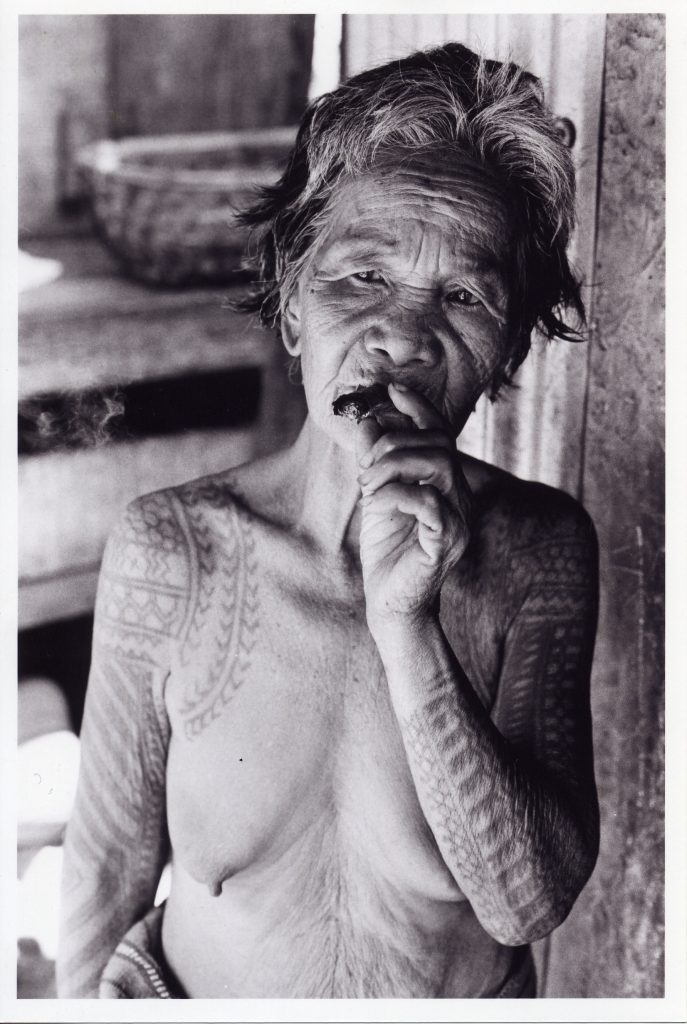

Kumafei from the Akerwan tribe took one day to do the fato – the tattoo. He worked fast but precisely. He took one large hog as payment. After five days there was no more pain.

The old man’s fingers trace over the rows of saw-toothed stripes across his chest until they rest for a moment at his nipples. Below here, he says, the needle hits breastbone. Below here, fato usually stops – too painful! The boys are all eyes and ears. A moment later his fingers go to his solar plexus where their tips follow a honey-comb pattern that wraps his abdomen.

One boy with a snotty nose, no more than four, repeats in air the movements of the old man’s fingers with his own tiny fingers; another, older, slaps the hand down. The old man makes a face, laughs. Sometimes, he says, when they are not playing, these village boys are men-in-the-making; they help him carry wood or rice from his field, even though their parents say he looks like a dead man – well, not yet! Sitting up straight, he opens his arms wide. Chin against chest, he looks down at his body then describes what he sees of himself. Look, he says, here, he says, on my breast. Where the left and right sides meet is the um umot. Remember. Here, under my chest, is the band of the kumlipao. Here, the chilog. One day you will be men, you will be our men. This is what our men look like, remember. Here, and here, and here. One day there will be nothing left to see!

4

He remembers the Japanese bombing of Kalinga and later discovered it was December 8, 1941. The Japanese came through the mountains fighting everyone, every village, and each one fought back.

Like the others, the village of Sumadel ambushed them from the cover of the forest. A group of five men had already laid sharp bamboo stakes – sugo – in the surrounding trails. This local mode of guerrilla warfare, native to Kalinga – bañgabang – was the preserve of older men, accustomed to prudence, stillness and biding time. But sometimes they took a patient younger man, like him, to acquire the art.

He killed one soldier with a spear, cut the head clean off with a head-axe and gave the jawbone to his village as a handle for a gangsa. Years after the war they would joke that some gangsa in the village were ‘made in Japan’. He meant his son to have it, to hide it as his people did, in the rice granary with precious blankets and family necklaces where each bead was worth a water buffalo, so that only a few would know where it was except at celebration time, when his son would play it, hold it between his knees, beat out the song, dance its music and remember aloud to the village what his father had done. But somehow, someone else kept the gangsa – it was a long time ago – and his son went elsewhere. His daughter, whose family he lives with, ducks out from the counter of the corner store she runs and brings him a bottle of Coke, removes his baseball cap.

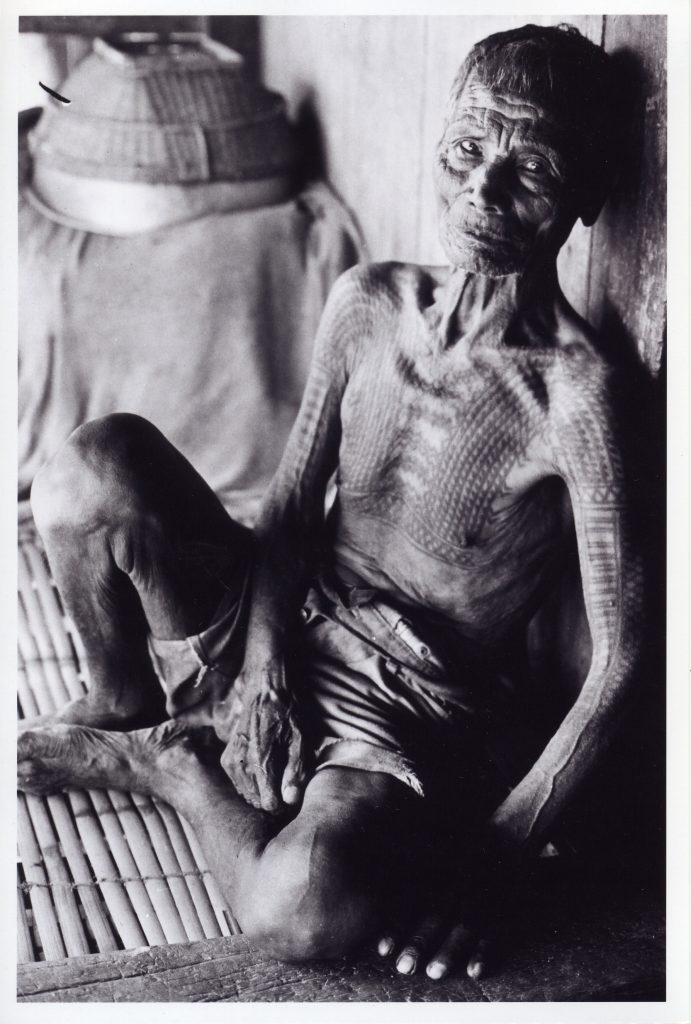

He was entitled to a fine tattoo and the tattoo man was very famous – Mañgortag – so he paid him a black pig up to the waist, tall. It took some hours for the stripes on his arms, then another day for a dozen centipedes to cover his nipples and shoulders, down his upper arms to where the stripes began. His could not move for two days and felt heavy for five. But a change had begun to work in him, a move toward a higher order of manhood. Yes, they treated him differently after fato. Men honoured him in many small ways, gave him pride of place at feasts, offered him courtesies, listened to his counsel. Women flocked around him – he was not yet married! Fato is the insignia, the outward sign of the hero. Only women who have the good fortune of having a hero in their family have the honour, even as children, of acquiring fato, though a family, of course, has many branches.

He took another head that year, another Japanese, and earned his second tattoo. In his village there were eight heroes like him, by some called headhunters. Maybe five, four, two, are still there. It isn’t so far from here, from this village, he says, but his knee, his leg, it doesn’t work anymore, it isn’t young. It hurts if he tries to climb the mountain, home. I don’t want to smile for you, he says, raising the bottle over part of his face, because I am ashamed. You will laugh at my old man’s mouth with only one tooth.

This piece and its accompanying photographs are from a larger work on the Philippines.

Black and white photographs, 2006

40.6 x 50.8 cm