Time’s Arrow

But first let me introduce you

to the family…

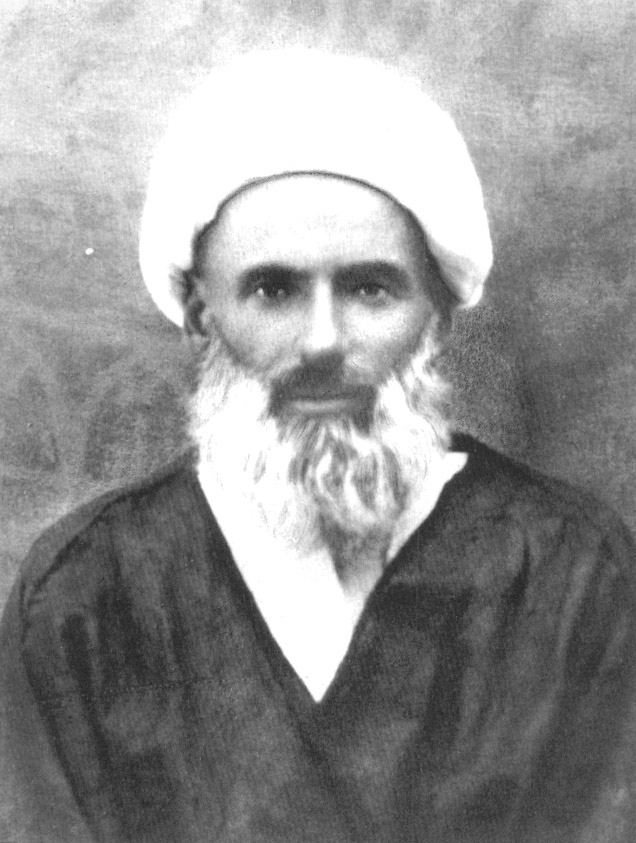

Men from five consecutive generations of my family, from my great-great-grandfather’s to my own, have moved away from their birthplace, either for a long period of their lives or for good. Around the middle of the nineteenth century, my great-great grandfather on my father’s side was invited by the people of the village of Jibsheet, a fifteen-minute ride from the town of Nabatieh, to become their religious leader, guiding them and presiding over their rituals of prayer, marriage and death. He was a Shi’a Aalim, literally a learned man or a scholar who can develop an understanding of the laws of God and apply them to daily life. He accepted the invitation, moved from his own village, some twenty kilometres away, and lived in Jibsheet until his death. My great-grand father followed in his father’s steps and became the village spiritual guide after studying for some years at the Shi’a religious schools of Najaf in Iraq. The few stories that my elder relatives told about him portray a rather stern man who adhered to a rigid interpretation of the scriptures and who saw himself as a guarantor of tradition.

His son, my grandfather, left Jibsheet to go to Najaf to become a religious scholar himself. It never really worked. A few years later, he caught tuberculosis while swimming in the Euphrates (to save a friend from drowning according to the optimists in my family). He cut short his studies and travelled back to Jabal Aamel, as the south of Lebanon beyond Sidon is known. Later, he became an unorthodox historian of the nascent Lebanese nation to which he belonged. (Another of his generation left the religious school of Najaf after a crisis of faith which led him to a long career with the Communist Party, until he was assassinated by fundamentalists during the gangster days of civil-war Beirut). My grand-father was a pan-Arabist who worried little about religious issues. His interests lay with the Arab Renaissance, the state of minorities in the Middle-East, the nature of Lebanon and the relationship with the West, rather than with matters of religious conduct to which he had a rather liberal, sometimes indifferent, attitude. Tradition in his view, with its authoritarian institutions and rejection of innovation, often froze our thinking in obsolete moulds that had to be broken if we were to rise and prosper as a people. He lived long enough to witness the rise of Shi’aradicalism in the early eighties and be dismayed by it.

My own father left Jibsheet, first for Nabatieh for primary school, then for Sidon for high school, and finally for Beirut where he trained as a teacher, worked as a school inspector for a few years, entered University, graduated with a law degree, then joined the civil service and rose in the hierarchy until his early retirement. He became part of the rising Shi’amiddle-classes who were often more integrated into city life than their co-religionists in the southern suburbs of Beirut, but still felt somewhat alienated by the city. (The traditional urban communities are mostly Sunni and Greek-Orthodox). He left the civil service disappointed by the political and sectarian machinations (or lack of them) that blocked his way to the highest non-elected rank in the system. Later in life, he wrote a doctoral thesis on Islamic law at the University of Paris, and tried to reconcile modernity with Islam by insisting that Islam is modern at its roots, and that the real tradition, unencumbered by false interpretations of the scriptures, had to guide us in dealing with contemporary issues, a line taken by a large number of reformers and traditionalists, ever since nineteenth-century intellectuals in Ottoman lands became fascinated (and troubled) by the West’s technological superiority and their political and administrative structures.

My father’s move from the small village of Jibsheetto Beirut – not so great in distance but fraught with difficulty – was to have far-reaching implications for our family. However, it was by no means exceptional. His case was one among thousands, and reflected the strong rural-urban flux that was reshaping Lebanon in the second half of this century. (The failure of the political institutions to cope with this socio-demographic change in a deeply sectarian country is largely to blame for the civil war that ravaged Lebanon from 1975 to 1990, the other destabilising factors being the Palestinian exoduses of 1948 and 1967, and the regional conflict in the Middle-East).

It was my father’s geographical move that brought us as a family into direct contact with the dynamic centre of power in the capital city, and the westernised educational institutions that Beirut offered. I was born and grew up in the city and went to a secular school run by the French while still living in a mixed cultural landscape which encompassed both Beirut and South Lebanon. My school was located in a street named after ‘Abdel Kader the Algerian’ – the nineteenth-century Sufi poet who fought the French relentlessly and became one of the most celebrated symbols of Algerian nationalism: the school had acquired the unlikely name of Mission Laîque Française, Lycée Abdel Kader to distinguish it from other Mission Laîque schools in the city. Piety, religion, physics, mathematics and Arabic grammar; Baudelaire, Racine, Ibn Sina aka Avicenna and Al Mutanabbi; Um Kalthoum and Jacques Brel; partying, dating and daily prayer; French restaurants, American hamburgers and Arabic desserts, all side by side in a great jumble that was not really a jumble because it was the only place I knew.

Even when, in my early twenties, nine years into the civil war, Shi’a militants from the southern suburbs of Beirut were to overrun the city and terrorise it for a while; even when I came to realise that the French pursued their secular ideals with an overbearing missionary zeal, those worlds were still part of me and must therefore, by necessity, remain compatible. I, and people like me, were the factories that maintained that compatibility, whether we liked it or not, and some of us did like it. Beirut, with its taut pluralism and cynical tolerance, provided living space for our hybrid selves. After all, we did not have a traumatic colonial past to contend with. This was not North Africa, where the language itself had been inextricably colonised. The Lebanese dialect is unmistakably Arabic; roughly a third of my school studies were conducted in Arabic, even though my school was French; most of us spoke Arabic at home and among friends; we watched foreign movies with Arabic subtitles. The French ‘mandate’ in the Levant only lasted around twenty-five years and had not entailed the level of violence that Algeria lived through. We could afford to think of our experience in terms of ‘multicultural richness’ rather than ‘identity crisis’ or ‘split personality’. It was perhaps easier for us, there and then, to learn that greatest of post-colonial truths: that you cannot wish part of yourself away.

Fortunate enough to gain two grants that saw me through my studies, I graduated with a Civil Engineering degree from the American University of Beirut, left Beirut for Europe in 1986 during the civil war to do my post-graduate studies, and lived in the UK, France and Lebanon over the following ten years before migrating to Australia.

Hergé’s Tintin is one place where the various worlds that made up my adolescence must have sat uncomfortably with each other. I read Tintin stories avidly as did many French-educated pupils in Lebanon. The gardens of the Chateau Moulinsart, where the adventures sometimes took off while Tintin was taking a stroll, were so delightfully different from the run-down concrete hulks of my own world. The colourful streets of Paris, as they emerged from the album, were clean, neat and peaceful, in stark contrast to the dusty clamour of Beirut. (Only later would I see for myself the hard cobblestones and the dog-turds of the streets of Paris, which, though they offered a more pleasant experience than Beirut’s, finally acquired a harder edge in my mind).

Tintin was an ideal friend, clever, adventurous and trustworthy, if somewhat sketchy and one-dimensional. He was more a vehicle for exciting travels than a real character. A pre-pubescent adult, he was morally upright, hardly ever revealed any yearnings or vices, and no women ever appeared in his life. His dog Milou and his friend Captain Haddock were far more interesting in this respect.

But Tintin traveled the world and explored continents, deep oceans, wild African jungles and nearby planets. He rubbed shoulders with Opera stars, South American Indians, Gypsies, Egyptologists, Indian snake charmers and Maharajas. To my adolescent mind, his qualities far outweighed any failings he might have had. At that time, I was not discerning enough to see how much more sophisticated were the stories of Goscinny, inventor of Asterix, even though I took almost as much interest in them.

Out of the seductive order and exciting adventures dreamt up by Hergé, there emerged a different view of the world, reflecting no doubt, his own prejudices and idiosyncratic inclinations. (In those days of course, Tintin had no author as far as I was concerned; it simply existed). Hergé did not refrain from referring to actual historical disputes and taking sides in them. Balkan kings fared well next to their villainous revolutionary detractors. China was a great nation that was misunderstood by the West and was abused, in colonial times, by a few nasty European businessmen, mostly Anglo-Saxon, and unscrupulous Japanese politicians. Scotland was a friendly if superstitious place. An endearing Portuguese trader kept cropping up and saving Tintin in times of difficulty. Chicago gangsters were easily outwitted by the hero and his white dog who were given a full-blown victory parade in New York. Much fun was poked at the Soviets and the South American guerrillas whose habit of shedding the blood of their vanquished enemies was only checked by the admirable firmness of Tintin himself.

The Arabs and Moslems did not fare well. Arab slave traders took advantage of African Moslem pilgrims on the way to Mecca and those pilgrims, we were made to feel, almost deserved it, so stupidly blinded by their religious quest were they. Arabs were effusive and simple-minded when they were not plain mean.1 Even the Arab-Jewish conflict was alluded to, and it is not hard to guess who were depicted as the villains.

A later edition of the same story went to the trouble of removing a mild reference to Jewish violence in Palestine when young Jewish activists, wrongly believing Tintin to be one of their own, seized him from the British soldiers who had arrested him. The revised version removed the Jewish characters completely, replaced the British soldiers with Arab ones, and attributed the same action to a mad Arab Sheik who abducted Tintin for reasons of his own. This Arab character, along with many others, already existed in the older version but had appeared at a later stage of the story.

The images conveyed by my surroundings, my teachers, friends and parents, and by my Arabic literature and history books were at odds with those of Tintin. A Sheik was a figure of wisdom to me not a subject of fun, and my own grandfather, whom I loved greatly, was referred to as Sheik Ali (though I suspected, even then, that this word had too many different meanings to be taken at face value). Pilgrimage to Mecca was a noble undertaking as far as I could tell, not a ridiculous quest by religious fanatics, regardless of what you thought of religion. As a child, I was disconcerted when I saw large groups of old men and women, the poorer pilgrims in their shabby white gowns, as they boarded air-conditioned coaches heading for a faraway desert, as crowds of poorer people anywhere may frighten a child from a relatively privileged background. But there was nothing futile or preposterous about them. And if I wasn’t handed down an entirely coherent view of the world, I was to discover later that this was just the tip of the iceberg: the world was made of contradictory images. I recognised this later when I revisited the Tintin stories again in my early twenties and, still later, when Edward Said’s Orientalism provided me with a new, illuminating angle on representation and colonialism.

If images clashed in my subconscious, there was conscious conflict too. One such was the change in the attitude to moral choice of different generations of my family. By moral choice I mean the way in which decisions are made in daily life when those decisions have an ethical or social dimension. Moral choice seems to have been largely determined by tradition and religion as far as my great-grandfather was concerned. Free will might be practised at all times and the right choices, sometimes down to minute details, were well-defined by a hierarchy of religious sources: the scriptures themselves as revealed in the Qur’an, the Prophet’s sayings and deeds, the Imams’ teachings and conduct and, so on. All you needed was a religious scholar, such as my great-grandfather, to show you the way. His world, although made somewhat larger by its links to the wider Shi’a world of Iraq and the religious schools of Najaf, was essentially small, rural and feudal. With my grandfather, moral choice had already shifted towards the political sphere: what mattered was political engagement because social progress and prosperity, it was believed, could only come as a result of political activism, which would undo the backwardness inherited from the Ottoman empire, European colonialism and religious conservatism. Finally, the religious revivalism of the seventies and eighties, to which my father is a moderate adherent, attempts to reconcile religion and politics and restore religion as a major component in the moral and political lives of individuals.

But I would like to single out another, less obvious, spectrum of comparison: if my great-grandfather who sought to transmit tradition and protect it from the subversive effect of time is at one end of the spectrum, my engineering education is at the other. And this is not so because of an a priori contradiction between religion and science. Such a contradiction, true as it may be, has nothing to do with the comparison. Rather, it is a difference in the attitude to time (and moral choice again), that the two ends of this spectrum seem to point at. If my great-grand father believed that the past must keep a restraining grip on the future, what becomes of this equation in engineering textbooks?

It took me a while to grasp the philosophy lying behind many engineering courses: managing time in order to bring about maximum change. What change? An entirely functional one: roads, concrete blocks, bridges. Engineering education is not usually concerned with tradition. I was disturbed to realise that Engineering Management, although a seemingly peripheral course next to Mechanics of Materials, Concrete Structures and Structural Analysis, was the quintessential engineering course. It taught students to bring about the required change at the lowest possible cost.

Cost, crude economics disguised as common sense tells us, is that of resources and labour. When resources are freely available or cheap, the only cost is that of extracting them, in other words, labour cost once again. Engineering is in many ways about managing time: people’s time as a commodity that cannot be squandered. And time is inherently associated with change: if the world yesterday was exactly the same as it is today, the chronological distinction would be unnecessary.

But there is more of course. The engineering approach to life is, to use two words that are often encountered in mathematically-oriented engineering textbooks, piecemeal or piecewise. A perfect world in the eyes of engineering consists of a sequence of simple tasks that achieve specific down-to-earth objectives. The only unity running through these tasks is their functionality with respect to some other wider task, higher up in the hierarchy. This is a transcendental system where functionality reigns. Engineers clearly define their field of action and work from there: the width of the central girder of the bridge is up to them to decide but the length of its span is not, because it is already determined by the breadth of the river. They must work out the exact carrying capacity of the bridge within certain limits dictated by the municipality, but they have no say in whether the bridge should or should not be built because of its negative effect on the local fisheries or the ferry business. Engineers, in other words, are taught to know their limits.

Having determined the variables and constants, engineers devise a plan of action, the embodiment of a model-plan, an algorithm, which chops up the project into little tasks that are easier to conceive of and carry out. Although this approach is practised by other professions, it often seems to define engineering methodology. Engineers are not trained specifically to observe, nor are they expected to be particularly good at understanding human nature or the way in which society works. There is little by way of the natural or social sciences in the undergraduate curriculum (apart from the laws of physics and the behaviour of construction materials which are quickly reduced to mathematical formulae). The concepts engineers work with are usually physical and well-defined. It is a combination of mathematical abstraction and analytic and problem-solving skills that is emphasised, leading to an approach that is both potent and deficient, potent in getting a certain job done under certain conditions and criteria of success, deficient in controlling, changing or critically appraising these conditions and criteria. Engineers, therefore, know their limits and are good at getting a job done.

The holistic approach to life that we inherit from childhood and religion is thus replaced by an algorithmic outlook. What engineering teaches you is that you don’t need a cosmic theory in order to build a bridge, which is true; and it subtly tells you that the less concerned with cosmic theory you are, the safer and cheaper the bridge is likely to be (if perhaps less beautiful, but engineering education is not very concerned with aesthetics). This is not to say that engineering has somehow generated these attitudes; rather, engineering is a medium where these ideas are predominant.

Within four generations, I found myself at this other end of the spectrum: from the world of my great-grandfather where a man’s duty is to transmit tradition, protecting it from the subversive effect of time, to one where tradition disappears completely and the only plausible raison-d’être of living is change that often sees itself as progressive per se. What’s more, in place of a holistic consciousness that sees a unifying thread running through all aspects of life, here was a world made of little disconnected tasks that could be carried out according to a self-perpetuating logic of functionality.

Another dilemma in my engineering career, perhaps a more significant one, is best illustrated with a little story. I was attending a seminar on wave propagation. The speaker, a visiting professor from the USA, had been staying in Australia to conduct the experimental part of a project funded by a Pentagon research institution. As it turned out, and as is often the case in engineering, a mathematically-titled talk had a very practical background. The purpose of studying wave propagation in this case was to develop the capability of the American navy to explode offshore mines remotely, prior to a landing. The speaker, a friendly civilian, illustrated the practical nature of the project by drawing an example from the Gulf War. As one of the options considered for the liberation of Kuwait was a marine landing, the mines deployed by the Iraqi troops could have been a serious obstacle.2 At this point, my mind drifted. Regardless of the particular context of the Gulf War, I could not help thinking that this man might have been talking about invading Lebanon or bombing Iraqi cities, Saudi Arabian oil fields or Vietnamese jungles and we would all have taken the same disinterested, perversely academic, interest in the matter. As if to pre-empt any attempt on my part to seek refuge in my new Australian identity, and to repress my outlandish sensitivities, a few minutes later the speaker added, without any apparent irony or malice, that the reason for conducting his experiments in Australia was that the American military could not get permission to conduct them in the USA, presumably on environmental grounds. The Australian government had offered its services. The audience, mostly Australian, let out a murmur of unease.

The background to an engineering project is a given or a constant that is considered to be beyond the scope of engineers, not least by engineers themselves. The moral dimension of going to war is not part of our algorithm; it is not one of the tasks that we can tick off. This is because the professional attitude, somewhat like that of a soldier’s, dictates that we do not see the decision to go to war as part of our competence. It is the competence of those who give us money to do our work, that is governments. And if we do believe that we ought to have an opinion on the matter, we consider that we should prevent our private opinions from affecting our professional conduct. Nor do we feel responsible for the act of war even when we have contributed in some fundamental way to the effort. In other words, the moral responsibility for what is a collective act is chopped up into fractions just as the military operation itself is made up of a large number of tasks carried out by different individuals and organisations. And if one is apportioned only a fraction of the blame, then one is more likely to round down rather than round up the figures. Just as time acquires an absolute, futuristic bias that makes it a bully of the past, rather than the reverse, so the moral dimension of our lives is kept apart from our professions, except when the consequences of our actions are immediate, direct and perceptible to us. Do your job properly…becomes the motto, even if your job is on the assembly line of a landmine factory.

I could have overlooked the Middle-Eastern reference in the seminar and shrugged it off as incidental, which it was. I could have reminded myself that at least there was no negative representation of the Arabs in the talk. I could have reminded myself of the indirect racial hostility that I have experienced in England where Arab bashing seems to be one of the few activities that the rural gentry and the urban working classes have in common. (A few months into my stay in the UK, the Sun newspaper carried the headline: ‘KILLED BY ARAB SCUM’, referring to the kidnap and murder, in south Lebanon, of an American army general). I have even grown tolerant of the well-meaning acquaintances who see a wife-beater and a child-kidnapper in every Arab man they come across. These stereotypes and this blindhostility, I say to myself, are perhaps no worse than my own preconceptions about parts of the world I have never visited.

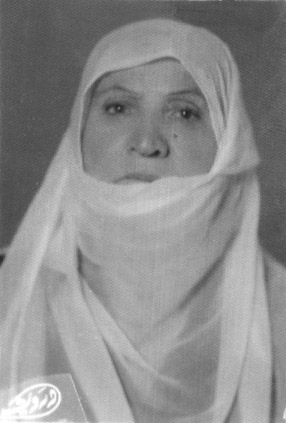

I could have had a different response altogether as I listened to the description of this weapon-design activity by the US navy, had I not experienced in my childhood and adolescence another feat of military engineering, a hostility of a far more tragic nature. In addition to the day-to-day violence of civil war, there was a violent death in my family. My maternal grandmother, a woman in her sixties, was killed in 1978 by an Israeli air raid as she fled the advancing Israeli army. She had been missing for more than a week when my uncle identified parts of her decayed body, largely dismembered amid the rubble of a house, from the clothes she was wearing. It emerged later that as the shelling and air raids had intensified, the car in which she was travelling pulled over in the village of Abbassya, on the hills overlooking the city of Tyre, and the passengers ran for safety. My grandmother was injured in the leg before she was carried into a nearby house, which was levelled by another air raid a few minutes later. She had been travelling with her sister-in-law and the little grand-daughter of her sister-in-law, who all died with her. Hours later, a few blocks away, more than a hundred civilians were killed when the mosque where they took refuge was flattened.

What lingers most in my mind from the episode – I was fifteen at the time – is the toll the event took on my mother, particularly because the mourning ceremonies had to be called off and then resumed as a result of the conflicting rumours that kept arising, one eye-witness confirming my grandmother’s death, while another reported her wounded at a hospital somewhere in Lebanon or Israel.

TSAHAL, as the Israeli army is called, has made the invasion of Lebanon a regular pastime, rolling in its tanks in 1978 (Operation Litani), 1982 (Operation Peace for Galilee), 1993 (Operation Accountability), 1996 (Operation Grapes of Wrath) and attacking again in 1999 (the prosaically named Operation Land, Sea and Air), at great expense to Lebanese civilians. As in many Israeli operations in Lebanon and elsewhere, American weaponry is frequently used. The question of weapon design by the US army therefore had a concrete implication in my mind and experience. The chopping-up and rounding-down of responsibility for war concerned me a great deal. Not because I believed that the world would necessarily be a better place if individuals made the right ethical choices – the causality is far more complicated unfortunately – but simply because under no circumstance did I want to be part of a war effort similar to the one that killed my grandmother.3

Robert Fisk, the Middle-East correspondent of the UK Independent Newspaper, once attempted to bridge the distance between weapon manufacturer and victim by smuggling parts of a US-made missile from south Lebanon back to North America.4 The Hellfire anti-armour missile had been aimed by a low-flying Israeli helicopter at a civilian ambulance, during the (lyrically named) 1996 operation, killing four children and two women. The ambulance was hurled by the missile sixty feet into the air and wedged into a house. Concerned about the practice of using anti-armour weaponry against civilian vehicles, which seems to have occurred more than once during the same operation, Fisk had investigated the story and interviewed a number of people, including the surviving father of the family, and the journalist who had filmed the atrocity. Parts of the exploded missile were stamped with its make and serial numbers, revealing the name of its US maker, whom Fisk arranged to meet in Atlanta without revealing the real purpose of the interview. Then he confronted three executives at the company with the missile evidence, the story of the south Lebanese civilian casualties and some photos of the victims. There was an eerie moment of silence as the presence of Fisk so improbably provided the missing link between cause and effect. At first, the executives cast doubt on the evidence then, admitting its strength, they expressed regret and embarrassment, but shrugged the responsibility off by stating that it was not really their job to find out how the rockets they designed were used.

Sometimes I think of the last moments of my grandmother, Sitti Um Abdel Ameer. I wonder whether she realised how helpless and slow the old Mercedes driving her and her companions was, compared to the state-of-the-art technology hovering overhead, whether she understood how pre-determined her destiny at that moment was by the difference in speed and perspective of the two engines. The driver could have sped through ten villages in under half an hour, the Fighter Jet would have caught up with them in under one minute. I wonder whether she overcame her fear for a moment, and paused to consider the technological making of her death, or whether she found it easier to consign the high-flying, droning monster to the realm of devils and evil spirits. I wonder how best to deal with my anger – at the manner of her death, at the vulnerability of my people. Although I believe in the overwhelming benefits that science, technology and the Enlightenment have brought humanity, a subversive metaphor keeps intruding on my mind. The past will no longer hold us back; with our wondrous technological innovations, we have ripped it to pieces.

About two years ago, I was stuck in a traffic jam on Corniche’l Mazraain Beirut, listening to the news on the radio. A middle-ranking Moslem cleric was raging against the proposed civil marriage law, which would have made it possible for a Lebanese couple to marry outside religious institutions, if they so wished. The law would have made it easier for a man and a woman from different religious communities to marry, and would have made inheritance rules fairer. Both Moslem and Christian officialdom opposed the legislation and eventually sank it. The cleric accused the proponents of the law of being agents of cultural imperialism and advocates of corrupt ideas imported from the West. He denounced his opponents’ lack of Assaala, authenticity, and their rejection of tradition. I found this offhanded confiscation of Assaala appalling – the way the cleric enlisted authenticity in the defence of his own power and prerogatives. I wondered where he drew the line of authenticity, what he thought of motor vehicles and whether he saw them as imperialist imports. As my car inched forward, I wished him a traffic jam on that day.

Three weeks later, I was stuck in another traffic jam on the Sydney Harbour Bridge. An American military pundit was on air, elaborating over the possibility of air strikes against Iraq to punish Saddam Hussein for his lack of co-operation with the United Nations arms inspection team. He was discussing possible targets in and around Baghdad, deploying the pseudo-scientific vocabulary that the American military use to make war sound as impersonal as heart surgery performed on a robot: ‘collateral damage’, ‘surgical strikes’, ‘remote sensing’, ‘target identification’, ‘night vision’ and so on. This misappropriation of science struck me as similar to the cleric’s self-interested usage of tradition. Science, as much as tradition perhaps, had to be fought over and appropriated. As the speaker moved deeper into his Star-Wars world and the residents of Baghdad failed to elicit a single word of sympathy or concern from him, I switched the radio off. Realising that the traffic jam was more serious than I thought and taking my eyes off the rear stop-lights of the car in front, I gazed at the amazing structure surrounding me, remembered how fascinated I was by the transparency and complexity of bridges, and lost myself for a moment in the charcoal steel truss built by my professional ancestors.

Had my great-grandfather been able to see the Sydney Harbour Bridge, he would have been moved by its beauty, regardless of any reservations a conservative cleric like himself might have had about the culture that had produced it. My grandmother would have been equally thrilled. My great-grandfather might have compared the bridge to his own architectural references, the Alhambra perhaps, or the mosques of Isfahan. He might have boasted his own architectural heritage to his Australian guide, or he might have confessed a pang of envy to a travelling companion. But whatever his attitude, he would have stopped and gazed and marvelled at the edifice.

There exists a space, unsullied by violence, racism and aggression, through which my ancestors may gaze at today’s world, across time, regardless of any cultural divide. Sometimes I think of myself as the conduit of that gaze. Migrants, particularly, find themselves fighting for that space and trying to preserve it, because the integrity of their lives depends on it. It makes their experience richer, while ensuring that their moral world is in tune with that experience. After all, if there is a such a thing as the ‘human project’, as Toni Morrison calls it – ‘to remain human and block the dehumanisation of others’ – then migrants have a very large stake in it.5

Then again, in my less optimistic moments, I think of myself as a hybrid who, when stuck in a traffic jam in one city, will consider it in the light of automobile congestion on the other side of the globe.

Notes

1 See Tintin au Pays de l’Or Noir, Coke en Stock, Le Crabe aux Pinces d’Or and Les Cigares du Pharaon (the corresponding English titles are, respectively: ‘Tintin in the Land of Black Gold’, ‘The Sharks of the Red Sea’, ‘The Crab with Golden Pincers’ and ‘The Cigars of the Pharaoh’). Hergé rejected accusations of racism in the case of Coke en Stock by pointing out that the only bad people in the story are ‘white men and Arabs’. This is recounted in all seriousness in Tintin: Hergé and his Creation by Harry Thompson in a book published in 1991 by Sceptre (P.166). The author, a BBC producer, has great sympathy for Hergé and depicts him as an artist hounded by what he calls the anti-Hergé lobby. Indeed, I was to discover that Hergé’s career is riddled with accusations of racism. One of his first stories, ‘Tintin au Congo’, written early in his career, is embarrassing in its stereotypical depiction of Africans, by the author’s own admission. The naïve Euro-centrism of the stories might not have been as offensive to non-Europeans concerned and might have remained a form of Belgian parochialism, if Tintin had not become such an international cultural product.

2 Fortunately, today, Civil Engineering consists of mostly civilian activities. However, the historical link between warfare and engineering is evident. Civil and mechanical engineering started developing independently from the military sphere at the beginning of the industrial revolution. See for example George Emerson’s Engineering Education. A Social History (1973).

3 Although there may be some truth in the saying ‘Guns don’t kill. People do.’, it does not follow that weapon manufacturers can be simply exonerated, if only because the kind of weapons used determines the number of people killed and the geographical extent of the killings. Whether it is a car bomb or a suicide bomb, an air raid, a shelling spree or a missile attack, the explosives, their range and power and availability on the market, are no less relevant to the action than the identity and motives of the perpetrators. The uncomfortable truth is that regular armies are far more likely to behave like unruly guerrillas, than vice versa.

4 See Robert Fisk’s article ‘Return to Sender. Is This Some Kind of Crusade?’ Independent on Sunday, 18 May 1997.

5 See Toni Morrison, ‘Strangers’, The New Yorker, Oct. 12, 1998, p. 68-70.