Only one refused

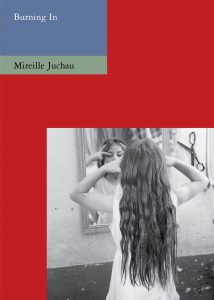

Even as I uncover materials that suggest Renate’s appearance – a portrait of her sister on an East Berlin balcony in 1961, prisoner records from age sixteen till liberation, a Hollerith card that catalogues her physical features – she remains stubbornly abstract, a dream that can’t be retrieved. I scan the women photographed at the Mauthausen subcamp and the summer women displaced in southern Italy though I can’t possibly recognise the one I’m looking for – Renate Grau. She’s an assemblage of Nazi documents, a set of symptoms in a reparations claim, one name on the postwar lists of survivors and displaced persons. Who can make a person from such traces? Despite this scarcity, despite five years of searching, I’m driven to discover more. Sometimes I’m unsure if I’m summoning Renate – an obscuring aura that heralds a migraine, an unquantifiable sensory fact. Sometimes our positions reverse and I feel my self dissipate as her form material ises out of the past. Then I’m haunted, in the ways Avery Gordon describes it, as unresolved social violence erupts directly or obliquely, and ‘…home becomes unfamiliar…your bearings on the world lose direction…the over-and-done-with comes alive…what’s been in your blind field comes into view.’

Renata Grau, Häftlings-Personal-Karte Mauthausen, DE ITS 1.1.26.8, 56960, ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archives.

On Renate’s Hollerith card her nose, mouth and ears are classified ‘normal’. Her face is oval, her teeth gut, her hair is Schwarz, her eyes are grey, or Grau like her surname. The card describes a body broken into parts considered suitable for slave labour, a human cog in an industrial system overseen by Deutsche Hollerith-Maschinen, IBM’s German subsidiary. Hollerith cards were used by the Nazis to manage their prisoners, and since IBM designed, made and supplied these cards, my portrait of Renate comes courtesy of a Nazi system developed by an American company, via the Mauthausen subcamp in Lenzing, Austria where Renate did forced labour in 1944. Ten years earlier, a facility using IBM technologies to process the census opened in Berlin. In his speech the manager, Willy Heidinger, prefigured the overblown claims, pseudoscience and lethal administrivia that would characterise the Nazi regime:

We are very much like the physician, in that we dissect, cell by cell, the German cultural body. We report every individual characteristic…on a little card. These are not dead cards, quite the contrary, they prove later on that they come to life when the cards are sorted at a rate of 25,000 per hour according to the characteristics. These characteristics are grouped like the organs of our cultural body, and they will be calculated and determined with the help of our tabulating machines.

Not dead cards, quite the contrary. The little card tells me Renate was 163 centimetres tall – the same height and age my daughter is now. She’s slim. With her parents, Hubert and Herta, she joined the 1,388 prisoners transported to Auschwitz on 12 October, 1944. They’d survived sixteen months in Theresienstadt, where 34,000 people had died of malnutrition. At some point Renate contracted tuberculosis. In Auschwitz, her parents were murdered. Soon after this event, which she will later describe as the source of all her suffering, Renate was sent from Auschwitz with 600 Jewish women to Salzkammergut, the mountainous region of Austria. It was just before the brutal winter of 1944. Most women were assigned to the local textile factory, Zellwolle Lenzing AG, to make rayon. From the scant list of dates and places sent to me by the International Tracing Service, I assume Renate, classed as an unskilled worker, was among them. At Lenzing the women worked under Frau Schmidt, Oberaufseherin Margarete Freinberger and Maria Kunik – each guard trained to recognise work slowdowns, sabotage and to perform something called ‘malicious pleasure’. One survivor who witnessed this training recalled that when fifty trainees were instructed to hit a prisoner, ‘only three asked the reason why they had to hit the inmate; only three asked the reason why, and only one refused.’

During my childhood I’d sometimes help my mother choose fabric from hundreds of patterned bolts. Her tight domestic budget meant she made most of our clothes, and like the daughters of countless refugees, she’d learned from her parents to sew. While she headed for the subdued cottons, I’d drift away to the novelty buttons and applique lace, to the synthetics, where my uncertain face would appear, distorted in the sheen. Choosing material was one of the few things I did alone with my mother, whose father once sold fabric in a Berlin department store until it was Aryan ised, though I didn’t know this then. My mother rarely spoke about her childhood, or her parents’ lives. Later, I associated this silence with the years of hiding her background in a culture that preferred neither Germans or Jews, and called this erasure assimilation, so I can’t help thinking that the muted fabrics she preferred were an extension of this passing. I would not be the kid in flammable nylon at parties or barbecues, better to fade out, or blend in. When asked if I think of myself as Jewish, a strange uncertainty overcomes me and I wonder about the false self that assimilation demands, a self which still must pass as real. I wonder what this performance might have cost my mother. Over time I’ve grown nostalgic for those fabric shops with their bread-and-camphor scent, just as my mother, while choosing fabric, perhaps reprised the suburban dress shop her parents ran decades before. Now, after researching Lenzing Zellwolle, when I pass my local Fabric City with its bright rayons stacked on the street I detect only a toxic base note.

At some point in this childhood I heard about Renate, my grandmother’s cousin, who was living back then in Tel Aviv under another name. I was told she was ‘damaged’, and since liberation, preferred not to be visited by any surviving family. Maybe because I’d developed a liking for solitude, and a habit of drifting into epic silences, I was privately awed at Renate’s demand, and what I understood to be her radical isolation. I didn’t know how to voice any wish, least of all a wish to be left alone by my family. The word damage stood out most particularly when my grandmother used Renate’s diminutive name, Reni. In a name-based synaesthesia, I pictured someone slight, fondly regarded, incompatible with harm. Later, I convinced myself her isolation must have been a form of courage and in dependence. I interpreted every fact through a teenage solips ism, yet I sensed something askew in this history. I hadn’t registered the way family stories rigidly fix us in the group and in the world they claim to describe – like a mirror in which we expect to see ourselves but find only an empty double veering from our surroundings.

Of all my grandparents’ stories about life before and after exile, it was Reni’s that took hold of me. So I requested everything the International Tracing Service had about the Graus. Eventually I received the Nazi records of Renate’s twelve years of persecution including the Hollerith card, and the lists titled Sh’erit ha-Pletah (surviving remnant) of the Jews who survived. Since my grandmother’s death there’s no one left in my family who can describe the precise nature of Renate’s injuries, though I’d always sensed these were more psychological than physical. Renate was absorbed into my childhood why, that answerless word, engine of my days. The mystery of Renate became inseparable from the mysteries of existence and, it seems to me now, from the puzzle of my self.

As I read about the carbon disulphide used in the factory at Lenzing, I began to wonder if this work was the partial cause of Renate’s ‘damage’ – the dangers of working with the chemical were already known in the nineteenth century when neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot linked it to hysteria. In Fake Silk, Paul David Blanc includes Charcot’s account of a man working in rubber production collapsing with ‘toxic hysteria’, his recurring nightmares of ‘fantastic and terrible animals’. British doctor, Thomas Oliver, noted the ‘extremely violent maniacal condition’ of factory girls exposed to the chemical in the rubber trade in 1902. ‘Some of them have become the victims of acute insanity, and in their frenzy have precipitated themselves from the top rooms of the factory to the ground.’ It was under the Third Reich that the most severe cases of carbon disulphide poisoning were recorded. At the Widzewska Manufaktura cotton mill in Łódź, Poland, several workers were said to have become so ill they were sent to an asylum and never seen again. Pure carbon disulphide is colourless and said to smell sweet, but industrial carbon di sulphide is yellow and smells like rotten radish. As I researched the chemical I found a photo taken through a microscope showing the effects of poisoning on the muscle, a close-up of swollen fibres and ‘waxy degeneration’ that resembled marbled fabric. I read about the disease’s ‘slow deceitful beginning’, and its further symptoms of ‘paraethesias, asthenia, difficulty in walking, mental deterioration, spastic paresis, alteration of speech’.

At Lenzing the women were woken at 3 a.m. for black bread and ‘brown liquid’, recalls Czech survivor Hanna Kohner. Her descript ions of camp life spare none of its depredations but pointill ist details reveal the women’s affinities. These ‘walking skeletons’ marched four kilometres from their Pettighofen barracks to the textile factory. They passed through ‘the cobblestoned village…along meadows, a dense forest and a small, clear stream’. Kohner doesn’t describe many local people in her account (written with husband Walter). You have to imagine them in their gabled alpine houses, the red flowers like gashes in the window boxes. Or read the work of survivor Jean Améry, who spent his childhood nearby in the Gasthaus zur Stadt Prag. The crimes of the regime entered my consciousness as collective deeds of the people. Two weeks after aborting a baby in Auschwitz, Kohner is ‘lucky’ to work on the Lenzing drying machines. Others slaved without protection over vats of steaming carbon disulphide used to turn fir and beech into fabric for German army uniforms. The women worked twelve-hour days. Some were blinded by fumes and sores opened on their hands, others developed menstrual disorders from chemicals known to cause birth defects and degenerative brain disease. Many died and those who became ill or injured were gassed nearby at Mauthausen. They worked through the winter, marching through sleet and blizzards. At night, rain and snow through the barracks ceiling. Outbreaks of dysentery, tuberculosis and typhus. Hunger oedemas and skin disease from poor nutrition. The youngest among them was twelve. By March 1945 the women were starving. They picked roadside herbs on their way to the factory. They cooked snails in machine steam.

In a photograph from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ten women stand outside the Pettighofen barracks. Some wear the striped jackets tied with rope sewn in the workshops of Dachau, Ravensbrück and Sachsenhausen. Isabel Wachenheimer, sixteen when she worked at Lenzing, wore a KZ‑ Frauenjacke of this kind. After her death in 2010, her jacket was found at her home in the Netherlands, wrapped in dry-cleaning plastic from the Rotterdam Hilton. I’m seized by these details – the plastic, which puts me in mind of a crime scene, the interval between young Isabel Maria of Germany and what transpired in that Rotterdam hotel. Most camp uniforms were destroyed after the war – they were stained, filthy, infested with lice or drenched in the DDT used for delousing after liberation. A man I know, a survivor who at ninety-nine continues to record the stories of others, lost his KZ jacket after his housekeeper took it to the drycleaners. Someone collected it by mistake, or perhaps it fell apart in a vat of perchloroethylene. In the Pettighofen photo only one woman looks young enough to be seventeen. She isn’t tall. She stands at the back of the group, head angled up between the women’s faces. I tell myself it can’t be Renate, headed for solitude. She’s too eager to be seen. Or perhaps I prefer to believe this than to imagine her waiting, after the war, to be found.

Among the 38,206 listed in the Mauthausen museum death book, are the nine women who died at Lenzing. Four of tuberculosis, intestinal obstruction and circulatory failure. I say died, but their injuries were sustained during their enslavement, and were, like the work itself, a slow murder. Five were crushed by a train on their way to the factory. Here’s how Margaret Lehner recalls it in her oral account:

[T]hey had to go there every day, early in the morning with their wooden shoes. And the winter was very strong. […] And most of them didn’t have any shoes, and they rolled paper around their toes and their feet. […] And one day um, there is a local train, a small train from Atnang-Pucheim to Kammerschorsling […] there was a bad accident […] you have to cross the railway to the train before the train is coming, and five women didn’t reach the other side […] And we, we think the parts of the bodies are taken to Mauthausen, to the crematory of Mauthausen, because they are, there are no names within the books of the date, of the people who died here. And we think with no names.

There are no names within the books of the date. We think with no names. Lehner’s faltering description of the unnamed women returns me to the Hollerith card on which Renate appears, in pieces, which is also how the Nazis referred to Jewish prisoners or labourers, using the word Stück. With some former prisoners Lehner organised a memorial to the women of Lenzing; she wanted ‘to make the history still alive’.

What else is a ghost but a disturbance in the flow of time. More than once I’ve hovered over items in a chain store, until registering with a jolt that they’re made from Lenzing fabric. Here, by a rack of flowing shirts in ecru, grey or mustard, under pitiless Zara halogens, I am haunted. The afterlife of state terror, genocide and slave labour erupts in such banal instances in everyday life; wholly private, practically invisible. It erupts in Lenzing’s ‘eco-fibre’, Edelweiss, named after the woolly white alpine plant that symbolises the local people’s purity. Edelweiss, which means ‘noble’ and ‘white’, was Hitler’s favourite flower. It erupts as I scroll through photos of the Lenzing complex for signs of its history. Clinical foyer and conference rooms, tiled factory floor, logs stacked outside. It erupts while viewing a company promo spruiking green credentials, ‘putting sustainability first…for the past 80 years’ even as workers at their Indonesian factory wash toxic chemicals from viscose products into the Citarum River, one of the most polluted in the world. It erupts during Banc’s tour of the Austrian factory, when he climbs the multi-level factory tower with a company rep who proudly notes there have been no suicides since 1950. Five years before that, Kohner watched the first liberators – a band of partisans looking like ‘a chorus from an itinerant opera company’ – approach the Lenzing camp. Schmidt and her fellow prison guards were preparing to flee. Schmidt seemed, writes Kohner, ‘to have lost her iron German nerves. She seemed to choke on something. Her eyes became watery.’ Her parting words before fleeing with Freinberger and Kunik, ‘und macht uns keine Schande’. Don’t bring dishonour to us. None of the women guards were ever brought to trial.

Years before I began searching in earnest, I found Renate’s entry in the Yad Vashem database. She was mistakenly listed as having died in the Holocaust. I wrote to the museum asking them to correct the record, wondering, even then, if Renate would approve. Maybe she preferred to disappear. I thought then of Imre Kertész who once received, in a large brown envelope, the Buchenwald camp records in which his death was recorded. Kertész recalls this in his Nobel Prize speech. He says, ‘I died once, so I could live’, but cautions against thinking his story apocryphal. He doesn’t want this to be an account of exceptionalism he says, accepting the litera ture prize. He prefers not to be singled out from the six million dead. What does it mean to search for a woman who so expressly chose to disappear, and to write her back into history? I recall Kertész’s novel, Kaddish for an Unborn Child, in which survivor György Köves refuses to bring a child into a post-Holocaust world. Köves mourns this child that he won’t conceive of, either literally or figuratively, and in the process grieves his own childhood cut short by deportation. Renate, it occurs to me, is equally inconceivable. If my attempt to bring her to life is both debt and guilt (in German the same word, die Schuld) it’s also a way to resist a family story that turned her and her ‘damage’ into a warning about who could be assimilated and who could not.

Some time ago, an editor who read another work on this history advised against my approach. It isn’t possible, she said, to combine epic historical events with smaller-scale contemporary material. War will always overshadow lives at peace, she seemed to say, or she was arguing for the Holocaust’s exceptionalism. I didn’t know how to explain that this shadowing was my very subject, and all the ways it threatened to obliterate me my deepest reason for writing. Only later did I see that prohibitions about representation can perpetuate the kinds of silence that took root in my mother, who’d passed to avoid the shame of being cast out and learned from the historic upheavals that splintered her family that major or minor feelings were comparatively inconsequential. This shadow remains with me still. It hangs about my writing as a ceaseless string of questions about which stories are mine to tell; what kinds of feeling are permissible; how much of myself belongs in this account or ought to be sublimated; whether leaving myself out is wilful disappearance, distortion or erasure.

When Luc Tuymans painted Schwarzheide concentration camp it’s said he had in mind a story about the prisoners there who tore their drawings into strips to keep them from being found. But Tuyman’s long vertical lines, which seem to reference that tearing, in fact echo a drawing by inmate Alfred Kantor which contains the same wintry trees, the same black lines fencing the page. Painting what an inmate might have seen, writes Ulrich Loock, Tuymans ‘takes the place of the inmate, to reproduce a substitute of something (trees) which he cannot reproduce (the concentration camp, death). The representation – hope-filled, fatal – of the other, who is oneself, is connected with the failure of the artist’s own representation.’ I recognise this failure in my attempts to recover Renate, the other, who is oneself, and how my acts of retrieval are similarly dependent on the accounts of others, partial, hope-filled.

I’ll never know if it was Renate’s wish to remain unknown – if she chose isolation or preferred to be recalled only as the young woman she was before Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, Lenzing and Mauthausen, the child who lived in Berlin with Hubert and Herta and sister Marion at Gustloffstrasse 17. It’s only by reading Améry’s sober work on exile that I can evoke Renate’s experience. ‘I rebel: against my past, against history…Nothing has healed.’ Like most of my family, Améry didn’t practice. In Salz-kammergut he wore lederhosen and was raised as a Christian. He called himself a ‘catastrophe Jew’, an identity forced on him by the Nuremberg Laws. Reading Améry – a person who could no longer say ‘we’ – I have a sense of Renate’s solitude. Améry can only say ‘I’ by force of habit. He says it without feeling in ‘full possession’ of himself. What’s left of the self when it hasn’t been held by family or friendship, by the machinery of the state? In her work on nostalgia, Svetlana Boym warns that ‘the moment we try to repair longing with belonging, the apprehension of loss with a rediscovery of identity’, we forfeit mutual understanding. Boym is thinking about exile and nationalism, but the same impulses spring up in a minor form within the family. Renate eventually received reparations under Germany’s policy of Wiedergutmachung (making good again) but this didn’t redeem life after liberation – as a maid in the Hotel Kinereth by the Red Sea; as an illiterate woman, married to an itinerant worker who beat her; estranged from what family remained across three continents. In Améry’s ‘analysis of resentments’, in his experience of exile, he recognises the ongoingness of estrangement – not just from the new home and the old, but from the self.

I still have no picture of Renate, though I’ve recently received the reparations claim lodged by her grandmother Jenny Badrian in 1952. Somehow Jenny escaped the transport that sent her daughter and granddaughter to Auschwitz, remaining in Theresien stadt till liberation. By lodging the claim she took care of Renate – who was by then living precariously in Tel Aviv. Within this 340-page file (its extent unnoticed by me until exclam ation marks arrived from the friend who helped me translate it), are reports from Renate’s specialists, clinical descriptions of her Lungentuberkulose, her Neurosis Schizoider Psychopathy, her ‘limited conceptual world’. After Theresienstadt, Auschwitz and Mauthausen, after years in the displaced persons camps on the Italian coast, after arriving, illegally, into a besieged Palestine in 1948, Renate was later hospitalised in Bat Yam, a psychiatric institution. A friend, deported from France with her mentally fragile mother to Israel in 1961, knows a little from her mother’s later, itinerant years, about life on the edge in Tel Aviv. Bat Yam, she says, was colloquial for ‘mad’. But it also means ‘sea daughter’. After reading these reports, the family story of willed separation gains the elaborate tone of myth. What if psychological illness, not ambiguous ‘damage’ kept the family distant, and even threatened their assiduous assimilation? In an account that offers no insight into what a uniformed man might signify to a former maid in an SS barracks, Dr Erich Goldschlager, Specialist for Nervous and Mental Diseases, reports that Renate once assaulted an Israeli policeman. Did her madness – entirely rational in the face of what W.G. Sebald calls, ‘the objective lunacy of history’ – also make her unassimilable?

If my searching has partly been an attempt to provide what Gordon calls, ‘a hospitable memory for ghosts out of a concern for justice’, I must also admit that it’s driven by a more personal, and possibly lifelong inquiry. What happens to the child whose temperament threatens the unspoken codes by which a family organises itself to survive? To belong to any group that forbids excess feeling is to relinquish genuine expression, mutual understanding. The ceaseless injury of being outcast can turn you into a detective, or a writer, who’ll prefer almost any other mystery than one that confirms that outsider status. In the Hollywood redemption story, Renate has broken from the family that preferred not to acknowledge her madness, and how expressly it communicated her rage and grief. She chooses freedom over conformity, longing over belonging. Here she is, sluicing water down the halls of the Hotel Kinereth. Here she is, in a maid’s uniform, zigaretten burning down as she stares across Tabariya, which is the Palestinian name for the sea of Galilee, and is no sea at all, but a lake.

Goldschlager attributes Renate’s trauma to the murder of her parents, to twelve years of persecution, to her lack of education and the violent husband she met in a displaced persons camp and divorced after a year. The doctor reports in German and his disparaging tone seeps through every machine translation. My Berlin friends, M and P, confirm this: ‘a sloppiness pervades the commentary,’ they tell me. ‘There is a disdain, even scorn for Renate – the writer seems to find her appearance offensive – seems to take it personally that she’s not attractive in a way he thinks appropriate, remarks on how her clothes are inadequate (nylon), she smells unwashed and has aged prematurely.’ A few lines restore her humanity. She loved her dogs and learning languages. She smoked 20–40 a day, despite her tuberculosis. She carried into the doctor’s rooms a primer used by schoolchildren from which she was teaching herself English. She had a passion for the cinema.

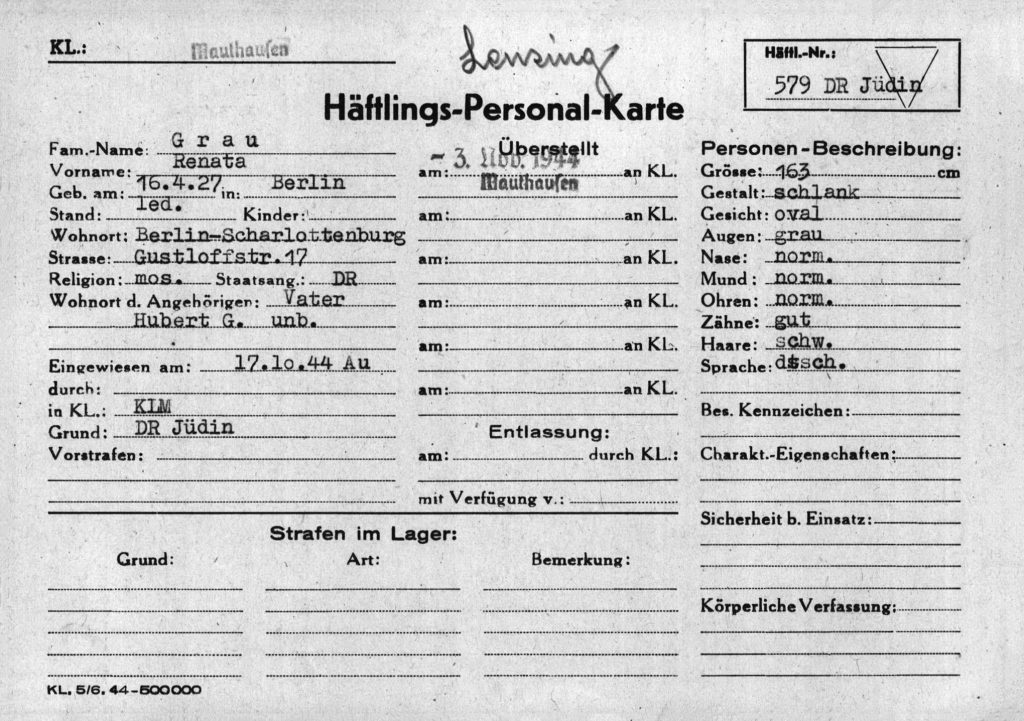

One day, searching archival images, I found a photo of women recuperating in the Mauthausen infirmary soon after liberation. Was Renate among them? The image is so overexposed that the wooden frames of the upper bunks look like windows full of sunlight. In the foreground a young woman, her face blurred and spectral from the long exposure. In every image from the camp I pick the most elusive figure and give her Renate’s name. There’s something unquantifiable in this photo, as if the whole scene were conjured by séance. But perhaps I only see it that way because the lives of women in the camps remain occluded, or because I want to fill in the spaces without distorting the picture. The blazing clerestory windows, the floating beds, the raw bulb in the foreground, the door at the far end of the hall opening onto nothing but glare. Somewhere beyond, camp brothels, once staffed by women from Ravensbrück. ‘Now we belong to Mauthausen,’ says a Hungarian survivor as she recalls their arrival from Auschwitz. In super-8 footage taken by the liberating army, she thanks the Americans with their k-rations of SPAM, powdered eggs, chocolate. ‘They made from us people again,’ she says in lilting, emphatic English. The infirmary photo is overexposed, a photographer friend tells me. Otherwise, with all that light from the windows, you wouldn’t see the women at all.

Survivors in the women’s barracks at the newly liberated lower camp of Mauthausen, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #38063, Courtesy of Ray Buch, Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Sources

Jean Améry, At the Mind’s Limits, trans. Sidney and Stella Rosenfeld, Indiana University Press, 2009.

Edwin Black, IBM and the Holocaust, Crown Publishers, New York, 2001.

Paul David Blanc, Fake Silk: The Lethal History of Viscose Rayon, Yale University Press, 2016.

Lizou Fenyvesi, ‘Reading Prisoner Uniforms: The Concentration Camp Prisoner Uniform as a Primary Source for Historical Research’, Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, 2006.

Avery Gordon, ‘Some Thoughts on Haunting and Futurity’, Borderlands, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2011.

Imre Kertész, ‘Heureka!’, Nobel Speech in Nobel Lectures, Melbourne University Press, 2006.

Imre Kertész, Kaddish for an Unborn Child, trans. Tim Wilkinson, Vintage, 1990.

Hanna and Walter Kohner, Frederick Kohner, Hanna and Walter: A Love Story, iUniverse, 2008.

Interview with Margaret Lehner and Yehuda Bauer, United States Holocaust Museum, 1994.

Ulrich Loock, in Luc Tuymans, Phaidon, London, 1996.

W.G. Sebald, Campo Santo, trans. Anthea Bell, Penguin, London, 2006.

Magdalena Zolkos, ‘Resentment, Trauma Subjectivity and the Ordering of Time’, Reconciling Community and Subjective Life: Trauma Testimony as Political Theorizing in the Work of Jean Améry and Imre Kertész, Bloomsbury, NY, 2010.

My gratitude to Michelle Moo, to Priya Basil and Matti Fredrich-Auf der Horst, Josiane Behmoiras, Saskia Beudel, Gail Jones, Phillip Maisel, Karen O’Connell and Maria Tumarkin.