Bushfire Journals

2 February 2002, Imperial Hotel, Clifton

Snapper & Chips on veranda. Second weekend drawing the burnt park. Room 3 has lovely view of ocean. Because the hotel is far above the sea – the window encloses a crazy perspective – you look down on a seething slab of blue. The main jukebox is under my room in the pub, which is a bit of a worry.

Today I’ve chosen a site to document for the next few months, as it turns from incinerated blackness and greenness flares up again. A passage of ground high up on Curra Moors which feels to me almost like some emblematic flag or heraldic statement. Take one rectangle. Divide down middle with narrow path. Left of this, burnt ground – with black skeletons of shrubs, trees. To the right, field of exuberant green – mosaic of living heath. Small trees and plants on the path are singed black or orange on one side, living green on the other. And beyond in the hazy distance there’s a great expanse of sea and the coast as it moves around to Cronulla and Sydney with its towers like a toy city on the far horizon.

Last night supper with Peter and Mindy and Steve Anyon-Smith and his wife Mayette. He wrote the Royal Park Bird Guide and is full of arcane bird knowledge. He was saying how attached to locality or place birds are. How Eastern Yellow Robins in the park have not gone to nearby unburnt bit but persist in fossicking about where their forest is burnt, faithful to their bare black and leafless ground.

In another area of incinerated park, he’d seen one living tree, which had been the territory of two yellow plumed honeyeaters. Several more homeless ones had come to join them. Result – civil war. I think I could paint those gorgeous cadmium yellow and pitch black feathers exploding out of that green tree and floating down to the sooty ground.

16 February, Imperial Hotel, Clifton

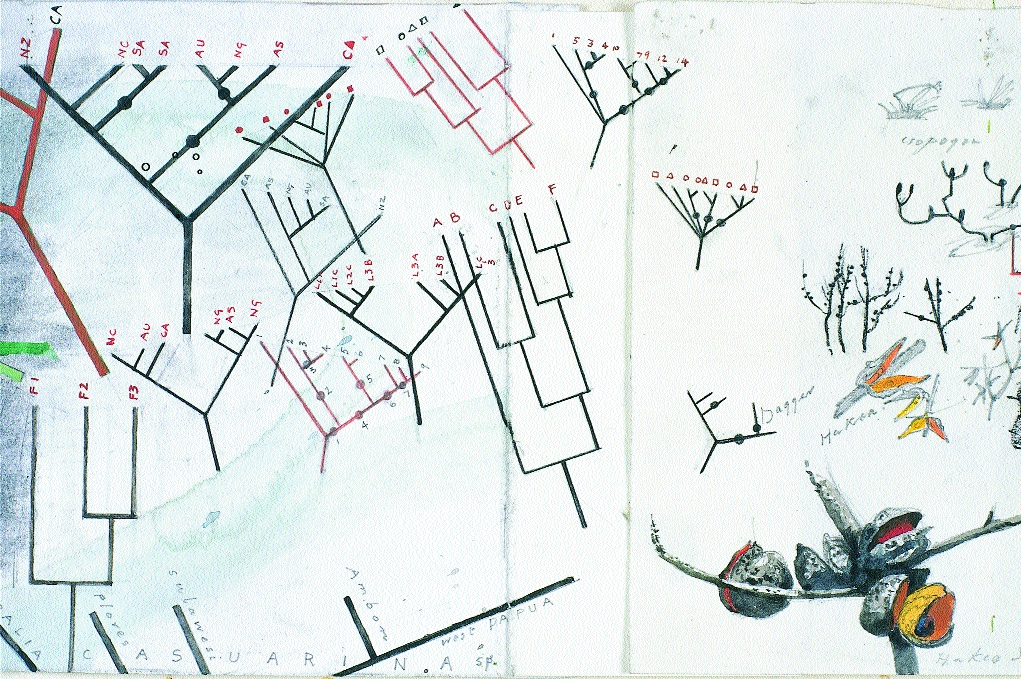

Shopped in Thirroul and got bread, sardines & pencils. Started drawing more of the Casuarinas on LHS. Good snooze in unburnt green bit and arvo drew a burnt Banksia stump and then some more Banksia branches – kind of syncopated. Not drawn yet – Hairy Needle Bush, Hakea Gibbosa. The slender stems studded with fruit capsules appear to be Leptospermum Squarrosum – Pink Tea Tree. There are five lovely Baeckeas. An Imbricatum which has green calyxes like Sydney Opera Houses strung kebab-like on stems; out of which peep little pink buds.

27 February, cave on road to Wollongong

Found excellent hidden cave to sleep in. Drawing No. 3. Painting in the Park for three days. Heavy rain for seven days has washed much of the recently released seed – Banksia, Isopogon etc – down to the Hacking River. Disney the science master said the potash-rich ash under the shrubs and trees is usually a perfect bed for the eager seed. These rains have washed much of it away. Today I drew some Dwarf Angophora and Isopogon stems and a strange Banksia which had a triangular base. But the way I’ve drawn it, it looks more like the head of a reindeer which has its body buried in the sand. I must de-deer this bit. New shoots at the base of many of the burnt shrubs have grown a lot since my first visit. Varied in colour, browny orange with yellow interiors to a rich verdant green with a halo of burnt cadmium orange – that’s the Grass Trees which spume out of their black bases like an army of bunsen burners.

Now some fifty days after the great fire: overall colour of ground pale sand with burnt sediment. No regrowth yet: Silky Needle-Bush, Isopogon, Personia, Porcupine Grass. Plants with fresh growth: Dwarf Apple – amber/orange up to sixteen inches; Coastal Banksia, with a twelve-inch explosion of strange apricot/khaki at the base of burnt stems.

16 March, Curra Moors, cave on old Princes Highway

Came via Kogarah – bought tarp for cave and poles and esky. The fire has stripped down the shrubs and small trees. Leaves, buds, textures of subtle bark, all pared down to the primary lineaments of the bare idea of Isopogon or Banksia. They are like Platonic ideal forms – the monochrome blackness of these skeletal shapes adds to the feeling that they are not real but some kind of graphic diagram of the essential nature of each tree. The candelabras with bobbles on the end of each twig are utter Isopogon. And the way the Banksia’s branching is a swoop up to each seed pod, and then divides into two or three stems each, ending in another furry explosion of fruiting body, is essential Banksia.

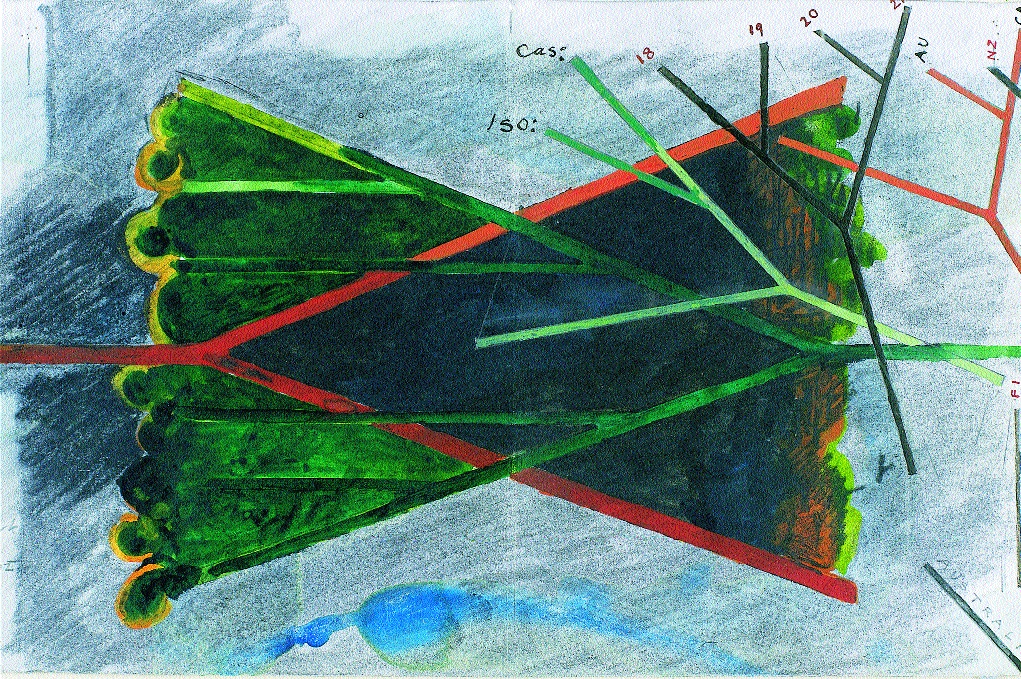

Yesterday I drew the shapes of the living tree next to a cladogram or family tree of its species – a diagram of its evolution since Cretaceous times. The diagram looks like no forest known to man – but perhaps to God? God’s Blueprint? The two types of ‘tree’ have something mysterious in common but I’m damned if I know what it is. Perhaps that Isopogon represents the furthest the plant world can go in being that particular plant form in its physical appearance in space now, while the cladogram form, showing the shape of its evolution, its ancient origin, might reveal its being in time – deep time. Not just dry diagrams but a dance of rhythmic energy. The main stems surge up from the ground in counterpoint to each other – I remember Utzon saying that he based his architecture on the spacing of tree trunks in a forest – and open out their smaller branches and twigs to the sun spaced at intervals in a way one can only describe as musical – perhaps a kind of percussion. Today’s Isopogon from above was a little constellation of white terminal fruits, each one punching the air rhythmically. Come to think of it…its popular name is Narrowleaf Drumsticks.

This morning’s drawing falls short of expressing this. But this afternoon something happened which was completely amazing. The strong wind was shaking my easel so violently I could hardly draw. Then the large piece of paper on its support crashed over on top of the Isopogon. And there – punctuating the surface – were the most rhythmic and lyrical charcoal notations. The little black fingers of the plant – arranged at intervals like some extraordinary drawing instrument holding charcoal sticks, had made staccato dots and marks of a kind I don’t think I could intentionally draw myself. So I then clipped some new paper to the board and gently and sometimes firmly moved the board on to and over several different burnt bushes. What was so beautiful was that the different charcoal twigs would land on the paper and then as I moved would register their sliding, almost syncopated movement, across it.

26 March, Sydney Grammar School, Sydney

I’ve pinned up six of the Bush Drawings. Don’t know what to call them – ‘Auto Frottage’ seems to imply something rather different. I described the random quality of the drawings to John Hughes and he said there was a word applied to some of John Cage’s music – aleatoric. I liked that musical reference…I haven’t quite worked out why, but these marks do have the feeling of being some kind of musical score or notation.

Now I’m wondering how aleatoric or random this process is. There is an element of chance about the way the marks land on the paper – but this system of working seems also to embody the idea that nothing is accidental, as the Taoists would explain. The charcoal fingers punctuate the air in the different branching modes peculiar to each species. And you could say, the pattern of marks they inscribe expresses the nature of that piece of land – the wind and climate, the low scrub habitat.

Then this blundering animal moves in with his drawing board. Random in a way…but I did try to move the board with a particular motion each time. Even to begin with some meditative Tai Chi exercises. Even to thinking that I was moving into the heath with a certain stride and rhythm and then the movement of the board would continue the flow of it and the scrape and dot and dance of it would be there caught on the paper.

6 April, Royal National Park

Greg Weight, Carol Ruff, Mike Cooper, Maria and I set off for the burnt Royal Park to do giant drawings, Greg to take photographs for his planned book, and Mike to record the process for the music to go with the installation at the MCA in November. As we drove on past Waterfall the great vistas of Heathcote National Park still looked transformed by fire, but compared with when I first saw it there are all those frills of new leaves up the trunks of the gum trees. Like pyjamas somebody said. We parked off the old Princes Highway near a kind of viaduct where huge pylons marched across the charred landscape.

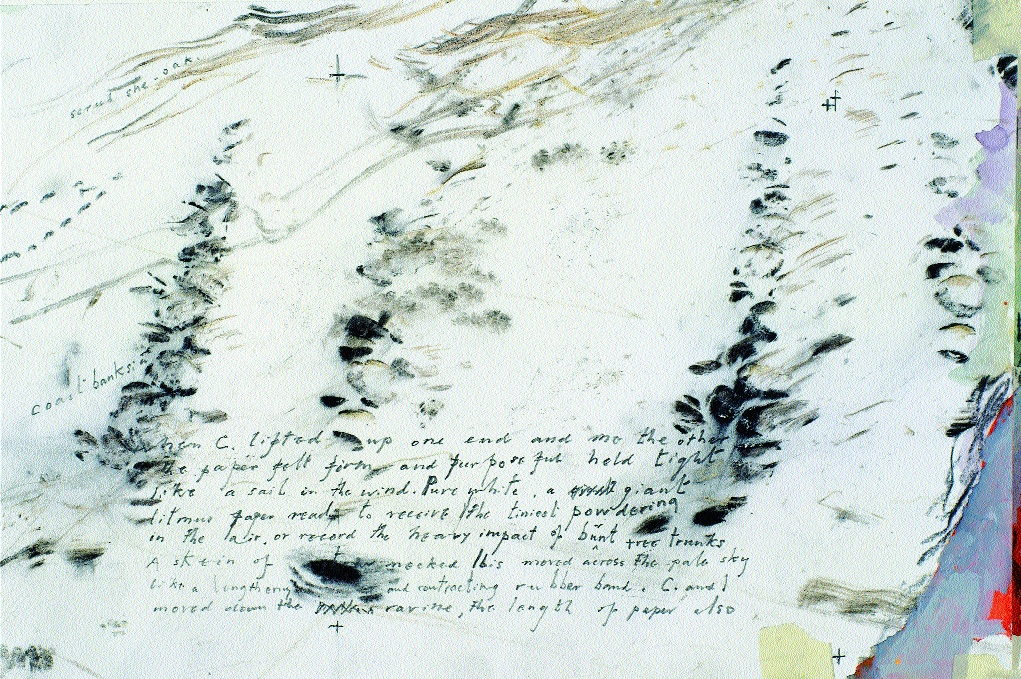

I unrolled the 5 foot by 30 foot roll of 300gsm Saunders’ and trapped a 12-foot length at each end with 2 x 1 strips of pine – nailed together. When Carol lifted up one end and I the other the paper felt firm and purposeful, held tight like a sail in the wind. Pure white, a giant litmus paper ready to register the tiniest powdering in the air or record the heavy impact of burnt black tree trunks. Just before we set off a skein of Straw-Necked Ibis – fifty or so – moved across the pale blue sky like a lengthening and contracting rubber band. There was one white bird, probably a lone Australian White Ibis which seemed to stay near the middle of this wavering calligraphy. Carol and I moved down the ravine, the length of paper also became a variable line – a snake-like contracting or tautening – as we wove between the burnt saplings. And even after only a few feet there were gestures and arabesques of tiny charcoal lines, fixing both our movement and that of the little charcoal twig fingers dragging and flicking back as we passed.

We crossed the motorway beside which several more traditional artists were painting large canvases on easels. Meeting of fixed versus nomadic. Peripatetic artists carrying long paper sailed purposefully past and disappeared into the burnt bush. It was like the encounter of two different species of animal – each group giving the other puzzled glances as they passed. Once into the bigger trees and more rocky terrain we moved slowly down where the hillside folded in on itself and there was a hint of a pathway. We had different kinds of encounters with four or five different types of tree – some we gently brushed against – and then there was a more coercive meeting with a big Banksia whose sooty knobbly bark left a passage of black scales on the paper as if a huge reptile had moved over it.

There were other times when I think we registered the effect of quite rhythmic interplay between us as we pulled the paper back and forth against the tree. And the tree was not passive. It moved its arms almost as if a wind was encountering them, forward and back, then flicking them away. Once the wind itself was blowing quite strongly and also took part in the mix of pressure and release. There were already strong strange patterns on the paper when we arrived at the intended main site. I wanted to register the subtle changes from tree to sapling to smaller scrub – following the natural progression – probably a watershed going down into a valley. Halfway down there were some slender delicate petrophile saplings at quite regular intervals, and these caressed, then dragged, then sprang away from the paper, as it was held flat rather than upright. These contrasted with the much tougher impact of rich carbonised stumps of dead trees, which left bands of black as we pulled the paper over them.

Bigger works like this suit a group collaboration more than the one-person works which are more a meditative communion with plant and tree. That day it was fascinating how serendipitously five friends all combined. It’s almost as if the paper had invisible vectors attached to it. All connected to the participants but with different energies. Mike hovered beside and over the movement with his small recording machine. I looked at him once or twice, and as he moved his head this way and that it was almost as if he was recording it with his ears rather than with the little machine. I wonder if the marks on the paper were altered by his presence, because I found myself enjoying and prolonging the scraping, scratching sounds for the benefit of his recording.

12 April, Imperial Hotel, Clifton

The images on the paper from yesterday’s drawing have the feel of a negative – a presence which is also a dark absence.

Some marks suggest other ashy flying things – sooty smudges like moth wings, or feathers or flying seeds. Perhaps those moths whose small white larvae are engulfing the green-amber new growth of the Angophora Hispida. Hispid leaves they are, with maroon fur. Where on earth did these caterpillars come from – eggs in the ground, or were the buried pupae ready to produce moths when the raging inferno passed over? Or did the moths colonise the burnt ground soon after the fires swept through the heath? Even as the embers glowed perhaps leaves of ash and those white moths floated down together onto the dark ground.

This heath is pale sandy-fire-bleached, looks as though it has had a black fishnet laid over it. The heavy rain has moved down the slope and eddied the unfixed ash and burnt detritus into arcs or pleats. Lots of fascinating things to draw in these ridges – burnt unidentifiable bits, and fragments of Isopogon, Leptospermum and other seeds, some of which are already sprouting. Soon it may be a green fishnet. Reminds one of those Mulga scrubs one sees from the air in the Northern Territory. A kind of fish-scale look caused by the same processes – eddies of water pushing ash of organic matter into ridges in which seedlings can burst up into trees.

This evening I left the drawing place at around 7.30 p.m. and drove towards Thirroul to the hotel. I asked for the key to my favorite room, number 3, which I had booked the week before. Arthur, the manager, inspected me and said that I was late and he had given the room away to someone else. ‘But I’ve been coming here for the last three weekends, don’t you remember me?’ ‘I’ve been here for a year and a half and I’ve never seen you in my life,’ he said.

After Arthur’s rebuff, and because he’d closed the counter teas early, I drove further down the coast wondering which novel or film the fellow had slipped out of. Perhaps he was one of those Conrad characters muttering in the cabin of a steamer on some jungle mud flat. There’s an Ancient Mariner quality too – ‘he holds you with his glittering eye.’ I remember Teresa W. remarking as we drove away one time that ‘he had a strange stillness about him’.

Last week he had approached me as I ate my solitary fish and chips on the moonlit veranda – possibly the only guest – and stood for several minutes telling me to expect heavy storms. ‘I know about weather,’ he said. ‘I used to be a pilot.’ He told me how the number of planes entering Sydney Airport had changed the weather patterns at Wollongong. ‘Aeroplanes shift a lot of air you know.’

I’ve ended up in a pizza parlour at Thirroul. Writing this surrounded by brilliant green and mauve walls and one pale blue one. On the green one there is a mural of a couple dining at a table with a huge wave about to fall on them.

Up there on Curra Moors this evening – such a lovely light – rays of sun from under piles of cumulous raking the burnt scrub, picking up the orange mouths of Hakea seed pods. Took a telephoto lens shot of a Regent Parrot – scarlet breast lit sideways as it sat on a dwarf Angophora and fastidiously picked off the white caterpillars. A quail-type bird flew towards the sea down the line where green meets burnt black. Some more Beautiful Firetail Finches flew across the line from cooked to raw. Each one rising and falling as if tied to each other – green nuggety things, with a slash of scarlet.

After I sat down in the pizza parlour an elderly woman shouted across: ‘Those pictures are by our local artist – made of seaweed.’ I politely got up and inspected the collages on chipboard of brown and ‘off’-brown which reminded me of old rooms with dry rot and exuberant fungi bursting forth. ‘Bit of an artist myself,’ I told the pizza man as he quizzed me from within his lime green servery window. He said: ‘Brett Whiteley died in the hotel down the road, did you know? Saw him the day before he died – blue eyes which looked right through you. That afternoon a whale shark beached itself at Thirroul. It had been ravaged by sharks, no fins, no tail, it was rudderless…like Whiteley,’ he said. Just now when he gave me my Mexicana with the lot he said: ‘That shark thing – that’s called a conspiracy of improbability.’

20 April, Imperial Hotel, Clifton

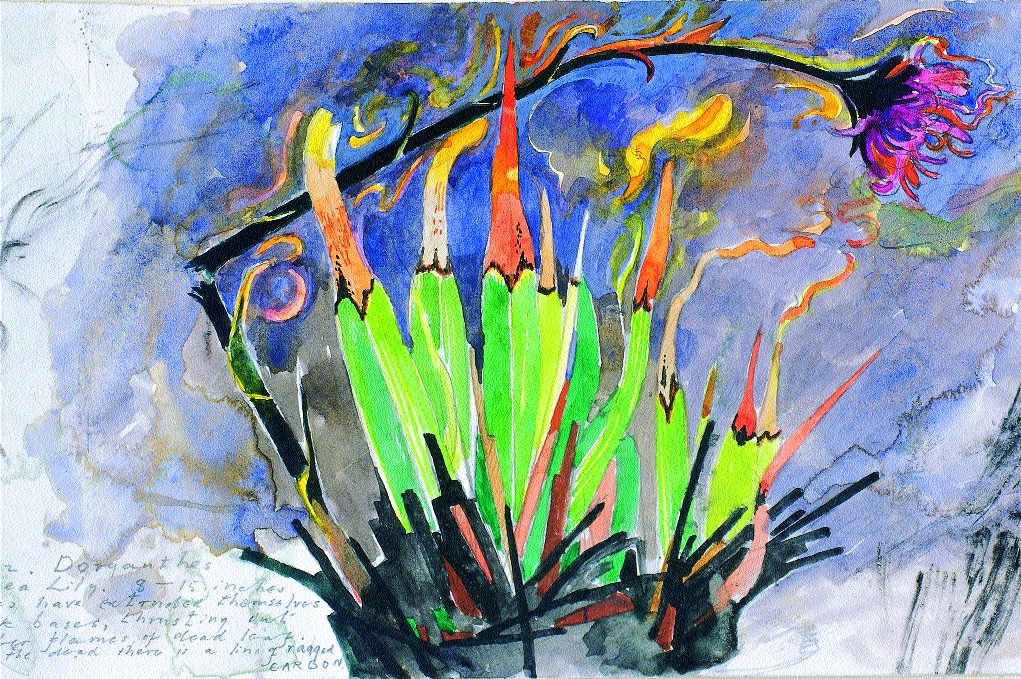

Good day yesterday – drawing a Gymea Lily which had extended about seven inches of leaf up into the air since the fires. It was as if each leaf was made of some green tape which, from a hidden dispenser underground, pushed up the orange spears of the original burnt leaves. Between the living and the dead there was a line of ragged carbon – a memory of that instant of raging fire.

I managed to get room 3 back again last night. Wild wind all night and even wilder dreams. At first I was on the beach below a forest with deer and horsemen, as if they had run out of the Piero di Cosimo ‘forest fire’ painting. There were birds fleeing, bits of wings and claws on fire whirling away in black clouds of smoke. On the sand there was a grand dinner party going on. Margaret Thatcher was helping me look for precious possessions which had fallen out of my suitcase all over the sand. I was desperate to find them before either the sea or the fire got to us. My anxiety was fuelled by the terrible sucking sounds which I’d heard when passing the Christmas Day fire – of primeval suction as the raging inferno consumed all the oxygen and pulled into itself the air from miles around.

It was as if one was sitting within an abstract painting by someone like Poliakoff composed of clearly defined blocks of paint, and the shuddering passages of urban buildings contracted and expanded against a block of bubbling green forest, which was then painted over by wave after wave of jade green sea.

At one stage the urban section expanded, and lunged towards the forest, pushing it into the sea, and Mrs Thatcher and I and the whole dinner party were smashed into the heaving water. I was sucked deep down and was drowning till I woke gasping.

Lying in bed in the Sunday morning stillness with my window of sea seemingly painted without brush marks, I did a drawing of the tumultuous night. I drew it as if the swelling and contraction of those elements of fire, water, forest and city represented the particular unbalanced dynamic which we have created on the earth. A different air with no protective layer of ozone, swelling the global seas till they rose to engulf a once-eternity of forest which, like a green nut in a nutcracker, was being crushed on the other side by an ever invading grid of metropolis.

I couldn’t work out where Mrs Thatcher or my suitcase figured in all of this, but my dream did seem to be saying something about the fate of the national park trapped here on its lonely escarpment.

Like when some geological or chemical model sucks in a proportion of the contents of the next one – or explodes in its pursuit of equilibrium – I felt as if my dreams had provided some solution to my ecological neuroses. And I was thinking that perhaps we should be looking at our planet’s ecological crisis in the light of such simple and obvious models when – my God! – what a scene of catastrophe greeted me when I went down the hall to the loo.

Great winds had hurled themselves down the cliffs and into the hotel bedrooms. In room 8 it looked as if they had surged into the hotel and had blown to bits the plastic Venetian blinds and then sucked them out again. It was as if a small biplane had hurled itself through the window. The tattered fuselage still writhed and creaked as the wind slammed the door open and shut. Two nervous fantails and several enormous spiders had been blown into the stairwell. In another bedroom there were more louvre bits flung all over the floor like green yarrow sticks. ‘Wild night,’ I said to Arthur. ‘Didn’t hear a thing,’ he said. ‘Someone’s made a hell of a mess in one of the bedrooms.’

11 May, Garie Beach Youth Hostel

Early this morning Curra Moors was calm and rain-scented under a washed eggshell-blue sky. Sometimes papery winged seed would float down from the needle-bush I was drawing or a bird would send a shower of snow flakes from the Isopogon bush.

I saw a chrysalis poking up through the sand – last night’s rain must have encouraged the Swift Moth to wake up from its secret metamorphosis from caterpillar to moth. I explored the ruby red interior of a Hakea seed capsule emphasising the sinews where the two lobes hinged; muscles which had so violently contracted in the heat to release the winged seed. In miniature there enacting those kinds of spring back to equilibrium which happen in macrocosm when volcanoes erupt or giant ice shelves break off into the sea.

25 May, cave near Wollongong

It’s now some twenty weeks since the fires. The high heaths and my site on Curra Moors are regenerating well, but this morning I walked along the southern part of Lady Carrington Drive and it’s sad to see how the tender new growth is being grazed down by the alien Rusa deer. I climbed up from Bola Creek to a sandstone ridge with ease and remembered how it would not have been possible to walk through the original luxuriant vegetation before the fire. I looked down on a small valley with some burnt Turpentine and Allocasuarina trees. Silent, no birds sang on the bare slopes. By a small creek red sap oozed from trunks of Green Wattle where the deer had ripped off the new stems.

It felt like a place in thrall, a wounded land – though I suspect ‘wounded’ is a bit over the top to describe a terrain like this where fires cyclically burn the landscape. Perhaps ‘dumbed down’ would be more apt to describe such a habitat which has lost so many of its original species since European settlement – the lovely Brindled Greater Glider, the Tiger Quoll, platypus, bandicoot, and the Regent Honeyeater and so on. Lost – because the unnaturally frequent succession of high-temperature burns is too much for them, and for the regeneration of trees which are often struck down before they are old enough to produce seed.

‘Dumbed down’ implies too that those plants and creatures have not got a voice. It is property and possessions in our society which have priority and speak loudly. Last week in a tutorial with twenty year-twelve boys I showed a slide of a Tiger Quoll, our beautiful marsupial wild cat. Not one boy could tell me what it was. I thought to myself…here is a culture which truly lives in a virtual world radically separate from the rest of creation. Not only did that animal not have a voice it did not even have a name.

I was so discombobulated by all this that I rang Peter Latz up in Alice Springs to share my indignation. He said, ‘Forget your pissy little park and its pussies. Up here there are areas of the Tanami and Simpson deserts as big as Ireland and Scotland which have been burnt to bits and the fires are still raging.’ He described how areas in the McDonnell Ranges like Simpson Gap were experiencing such repeated incineration that drastic things were happening to the biodiversity. ‘Introduced Buffalo grass and global warming, mate,’ he said.

I put the phone down and puzzled about why they were being allowed to burn like this. And why I hadn’t read anything in any of the media. ‘That figures,’ I thought. ‘What price a vast desert with a thousand different habitats and not even one “still voice calling in the wilderness”?’

2 June

Jenny and I met Peter Hay at 9.30 at the Ranger’s centre, and he drove us to Heathcote National Park which is out of bounds to the public while it is recovering from the big fires. Turned off the old Princes Highway along the road to Woronora Dam. We stopped once to look at the regrowth on the side of the road. The petrophiles were at last beginning to sprout at the roots. Lovely clumps of miniature acanthus leaves at the base of the black antlers of burnt shrub.

Entering the hills and deep valleys we could still see how the ferocious tongues of the fire fronts raked the park. There was a brindled burning, a striped sense of the landscape caused by advance forces of fire surging forward in great licks. Darker, totally incinerated strips of ground lie next to less fiercely burnt bits. We drove to some hanging swamps or flatter valley-bottom swamps which had lots of very green regrowth of a kind of sedge – Gahnia and even greener ferns under a veritable grid of completely burnt skeletons of Banksia. A kind of exoskeleton. I looked at one pool in the lee of stacked rocks full of tadpoles from frogs buried deep in the ground as the fire surged over the top.

We were philosophising about these and how such water bodies become centres of regeneration, and Peter described another example of energy radiating out from a central source. Shortly after the great fire he had found a dead half-burnt wallaby. Feeding on it was a mass of blowies and a huge goanna chomping away. Death keeping the lizard alive; and birds fluttering over the lizard’s head catching flies. There was a ripple of maggots under the skin and a swishing loop as a hawk dived down and carried off a fantail. Radiating bundles of nutrients, as one kind of living thing metamorphosed into another and spread out to colonise the dark landscape.

Later, when Peter dropped us at headquarters, he gave us a key and we returned to do another giant frottage drawing. We found a good place near a steep burnt hillside. I added to my communication techniques with the different trees. Twice there were places where twigs and branches had collapsed on the ground and lay as braided or parallel passages of burnt charcoal – maintaining their twig shapes like layers of bought charcoal in a box. Here I placed the paper over them – put one foot on one side of the paper and pressed the other sole rhythmically at intervals over the burnt bits. The result was a lovely ‘thank god for dappled things’ kind of print. The ‘printing plate’ could only be used once; the second time the charcoal had no definition and had become charcoal powder. An interesting progression of physical nature which had changed from being living green branches of leaves to black platonic ideas, then to undefined evenness of undifferentiated matter.

3 June, cave on road to Wollongong

Today is my last visit to the park before I hang up some of the works at the Hazlehurst Gallery with the other artists. Something fulfilling about completing this group of drawings at the same time as Curra Moors’ surge of renewal has got under way – it’s bursting into leaf and into flower. As I stood where I had done my first tentative drawings in the burnt landscape some five months ago I felt quite tearful at the sheer energy and abundance of it. The singing of birds in the frills of leaves all up the branches of the Port Jackson Mallee. The army of grass tree spires flowering between luxuriantly green clumps of Gymea Lilies. And every conceivable seedling exploding out of the sand. The sound of bees and bird song and the whirring of an unseasonal cricket all added to the feeling that I was standing within some wonderful organic machine which was driving this renewal. The tower blocks of Sydney just visible in the hazy distance – ‘the still sad music of humanity’ and the recent aggressive posturing of its world leaders seemed far away, existing in a more temporary dimension than did this great surge of energy – this ancient cycle of regeneration. At dusk I rolled up all twenty-five drawings and took them to the city to show what I had seen.

The editor wishes to thank Sydney Grammar School for its generous support, which allowed the use of colour reproductions in this feature.