On ‘Sighs Too Deep for Words’ by Helen Garner

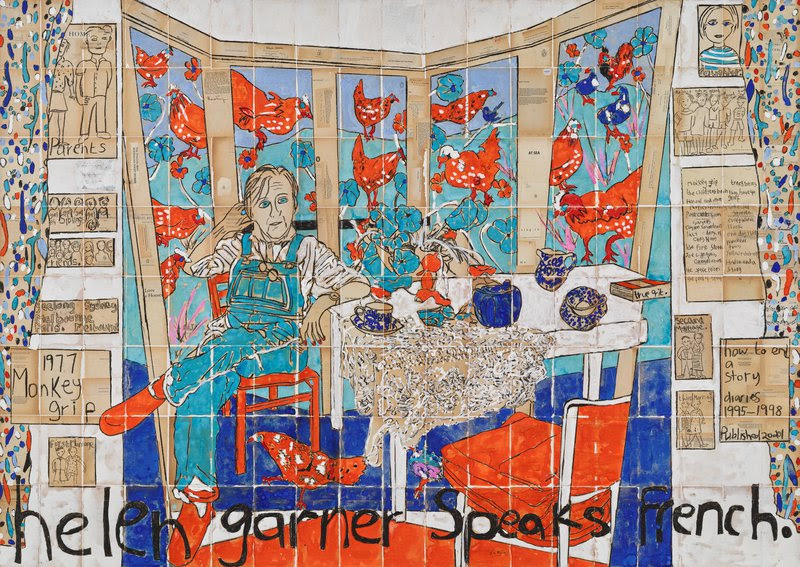

Katherine Hattam Helen Garner Speaks French 2022

I was on the phone the other day, chatting to someone who was telling me enthusiastically about the 2024 winner of the Archibald Prize, Laura Jones. I’ve never been a follower of this aspect of Australian culture – don’t have the eyes for visual art – so I have missed important details about the entries this year. I make a joke about Gina Rinehart, the only relevant fact I’ve managed to absorb from the zeitgeist. My interlocutor tells me to look up the portrait of Tim Winton, but whether the line crackles at just that moment or I transpose the letters in my head or perhaps am not listening properly, my mind half-elsewhere, I hear the name Tim Minchin.

Even as I obediently Google the portrait and stare, commenting on the clear talent of the artist, the expression in Winton/Minchin’s eyes, it takes me a full minute to cotton on to the misunderstanding. I only figure it out when my interlocutor says, ‘He’s quite Christian,’ and I say, ‘Really?’, somehow knowing to hold back my immediate thought, which is, Didn’t he write a famous song about being an atheist?, and my interlocutor responds, ‘Yeah, it’s all the way through his work, if you read it carefully.’

Later, I tell my friend Tim the story, filled with a combination of amusement and shame. Tim has a degree in English literature, and although by day he is a lawyer, he reads a lot and well. He is also one of those people who, walking down the street, might stop to appreciate the way the light strikes an object, a visual sensibility so finely tuned that he has even had a cathedral window tattooed to his bicep (that, and he was raised Catholic). He’s often quipping that there are cathedrals everywhere for those with eyes to see, especially when I have failed to appreciate the beauty of some thing or another. I don’t have the sensibility for it, I remind him – what I mean by that is that I am a depressive.

We get to talking about the Christian themes in Winton’s work, and Tim says, ‘It’s pretty clear in Helen Garner’s work too.’

I mishear again, responding, ‘Who is Hilary Chapsworth?’

‘Oh, Eda,’ says Tim.

In her 1999 piece, ‘Sighs Too Deep for Words: On Being Bad At Reading the Bible’, Helen Garner stages more than one exchange with Tim Winton about their shared faith, asking him his thoughts on prayer and God. Winton talks about the power of letting himself be moved by bible stories, and giving oneself over to their emotional truths. Garner reflects on this too, moments when reading the bible has offered her great solace, when she has allowed it to. I have worried lately that I am unreachable: not a good enough reader, listener, or person, a worry that intensifies when I realise that Garner, and Winton, are so capable of producing beauty because they know how to consume it.

But Garner also writes, with characteristic self-deprecation, about these worries herself: her fears that she is a bad reader – not disciplined enough, not knowledgeable enough – and of the times she has been too hard and or too numb to be moved. Reading this piece offers a kind of solace. She writes: ‘There was a time when it comforted me to see a daggy sign on the front of a fundamentalist church in Newtown: “God loves you, with all your troubles.”’