Uncategorized

Cold Enough for Snow by Jessica Au is shortlisted for the 2023 Miles Franklin

Jessica Au’s novel Cold Enough for Snow has been shortlisted for the 2023 Miles Franklin Literary Award. The announcement was made on 20 June by Perpetual, the body that manages the award.

According to the judging panel: ‘The 2023 Miles shortlist celebrates six works that delve deeply into archives and memory, play confidently with style and structure and strike new grounds in language and form…this is novel-writing at its freshest and boldest.’

Read their comments on Au’s book below.

Based around a finely observed account of a mother and daughter holidaying in Japan, Cold Enough for Snow is an elegant short novel that reflects on the twinned mysteries of life and art. The calm surface of Jessica Au’s superb prose creates a languid, dreamy atmosphere that belies the novel’s true emotional depth. Her narrator’s reflections move fluidly between past and present, summoning a web of memories whose meanings seem at first to be ambiguous and elusive. The acuity and sensitivity with which Au registers the distances between her characters, their small failures of communication, their unspoken feelings of unease, is one of the novel’s triumphs. Au’s uncertain and possibly unreliable narrator is nevertheless ingenuous in her restless desire to understand, a desire that finds its focus in her meditations on the mysteries of art. In an understated way, Cold Enough for Snow is a novel that, in asking questions about the enduring power of art, becomes a subtle reflection on its own process of creation. Its search for an entree into the mysteries of art is a search for a way to capture the disquiet at the novel’s core, to find resonant symbolic expressions of the narrator’s regrets and doubts. Cold Enough for Snow is a sublimely atmospheric novel that considers the transformation that occurs when an experience is drawn into the realms of memory and art; a novel respectful of the fact that when a moment is captured something is preserved, but something is lost.

Au’s book has now won four awards (including the inaugural Novel Prize), been shortlisted for six, and longlisted for three.

The 2023 winner of the Miles Franklin will be announced on 25 July 2023.

Author events

A (relatively) up-to-date list of events featuring Giramondo authors, including book launches, festival appearances, readings, and more.

Tuesday 23 April 2024

Manisha Anjali in conversation w/ Izzy Roberts-Orr

Readings Carlton (VIC)

Learn more

Wednesday 24 April 2024

Book launch: Television by Kate Middleton

The Crystal Palace & Courtyard (VIC)

Learn more

Sunday 28 April 2024

&& w/ π.O. and Autumn Royal

Randwick Literary Institute

Learn more

Tuesday 30 April 2024

AVANT GAGA w/ π.O.

Sappho Books (NSW)

Learn more

Wednesday 1 May 2024

π.O. in conversation with Ivor Indyk

Gleebooks (NSW)

Learn more

Thursday 9 May 2024

Poetry evening w/ Manisha Anjali

Eltham Bookshop (VIC)

Single entry ($40) / Couple entry ($50)

Sunday 12 May 2024

Melbourne Writers Festival: Alexis Wright

State Library Theatrette (VIC)

Learn more

Sunday 12 May 2024

Melbourne Writers Festival: Grace Yee

State Library Theatrette (VIC)

Learn more

Monday 13 May 2024

Melbourne Writers Festival: Grace Yee

State Library Theatrette (VIC)

Learn more

Saturday 25 May 2024

The Tribe: Anniversary Launch w/ Michael Mohammed Ahmad

Better Read Than Dead (NSW)

Learn more

Monday 27 May 2024

The Next Big Thing w/ Manisha Anjali

The Moat (VIC)

Learn more

Andy Jackson wins Prime Minister’s Literary Award for Poetry with Human Looking

Andy Jackson has won the 2022 Prime Minister’s Literary Award for poetry for his collection, Human Looking. The announcement was made in December at a ceremony in Launceston, Tasmania.

The book, which gives a ground-breaking insight into the experience of disability from a distinguished poet lives with Marfan Syndrome, also won the ALS Gold Medal and was shortlisted for the Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards.

Read the judges’s comments below.

In Human Looking Jackson shows he has a highly distinctive poetic voice, and writes with great technical skill and variety. Starting with its ambiguous title, Jackson’s book is an extraordinary poetic exploration of his own disability – Marfan’s syndrome, which is disfiguring and distorts the shape of his face and body. His poems are blistering in their power, wonderfully subtle, objective and with no self-pity. The first poem in this book ‘Opening’ plunges straight in to the main subject, and deals with corrective surgery – the long incision, which his condition required. But Jackson does not stop with the physical incision. He confesses “the long suture ruptures/ in my head – the scar remaining open.” What happens to our bodies becomes our mind. Astonishingly he takes this yet one step further. Through his poem, Jackson tells us, you the reader “are becoming/ this unstitching, this sudden opening.” Jackson does not falsely valorise suffering – suffering is suffering – but it opens us. He is able to rise above it, feel love and empathy, and accept himself. In his poem ‘Borne away by distance’, referring to Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’, he writes of “I, this wonderful catastrophe . . . turning toward/ tremendous being.” Tremendous indeed. And beautiful.

— 2022 Prime Minister’s Literary Award judges

You can listen to Jackson talk about the book on The Garret Podcast and on the Poetry Unbound podcast.

Eleanor Goodman: a note on In the Roar of the Machine

From translator Eleanor Goodman’s introduction to In the Roar of the Machine by Zheng Xiaoqiong (July 2022).

Zheng Xiaoqiong’s poetry brings to the fore issues of Chinese domestic migration, global capitalism and income disparity, the contemporary Chinese poetry scene, geopolitics and the world economy, feminism, wage discrimination, and workers’ rights. Quite aside from the sociological import of her work, it is Zheng’s own unique poetics that gives life to these issues, providing a powerful experience through which readers can understand and empathise with often overlooked people, including workers, women, and the rural poor. Although Zheng has published several books and her work has been enthusiastically received in China and in international poetry circles, her poetry has typically been viewed under a narrow rubric, namely that of ‘migrant worker poetry’ and the ‘migrant worker poet’. While this is where Zheng’s literary career began, it is only one part of the story of Zheng’s life and work.

…

From the start, she wrote across genres, producing essays, fiction, informal reportage, and poetry; the juxtaposition and melding of these different modes of writing are characteristic of her style. Her poems sometimes seem to slip towards prose, and her ability to capture voices and experiences that are not her own shows an ear highly attuned to both song and narration. Much of her work comes from her own direct experience or observation, and pulsates with linguistic, moral, and narrative intensity…Zheng has resisted the limitations of the moniker of ‘migrant worker poet’, however, and the concomitant role assigned to her first by birth and circumstance, and then by the literary establishment. Most of her poems having to do with the factory involve a larger context, whether it be globalisation, feminism, or environmental degradation.

…

To translate her poetry requires a knowledge not only of the vocabulary of the factory and the urban village, but an attention to her delicate gradations of tone and diction, which address the lives of migrant workers and also engage with classical Chinese poetry, global inequality, her family history within its complex cultural context, and the flora and fauna of her home. Most important, however, is Zheng’s voice, which can be tender, urgent, imploring, regretful, and learned in equal measure. I hope these translations offer all that and much more to the reader.

— Eleanor Goodman

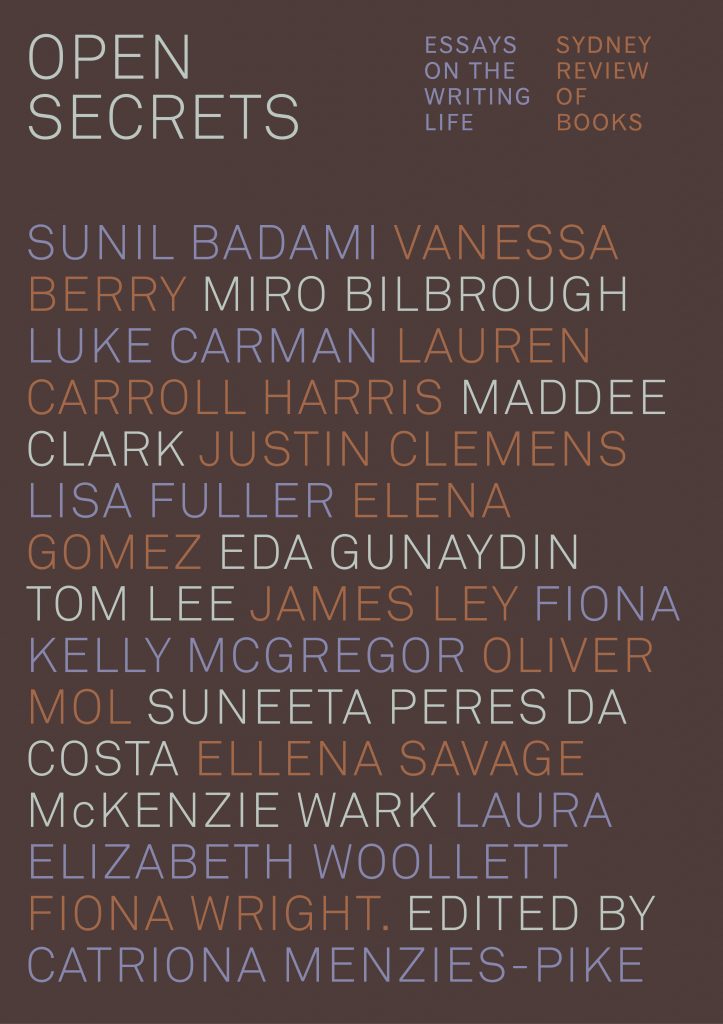

Catriona Menzies-Pike: a note on Open Secrets

Open Secrets: Essays on the Writing Life is the new collection published by the Sydney Review of Books and edited by Catriona Menzies-Pike. The following, written by Menzies-Pike, is from the book’s introduction.

The first myth about literary work in Australia is that writers don’t actually do much of it. Debauched, unworldly, undeserving, lavished with more public money than they deserve – they enjoy a sinecure funded by taxpayers, for which privilege they are asked little in return. Read, write, lounge, scrounge. The second myth is that to be a writer is to have answered a divine call. If writing is a vocation, it’s hardly work. Do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life. Bit rich to expect to get paid. Yet the reckless bon vivant and the worthy ascetic actually have few living counterparts in the corps of contemporary Australian literature. Most Australian writers don’t get paid much for their work, not by publishers, not by readers, not by the government – which is hardly to say that they shouldn’t.

So how – and why – does the work get done in a world that measures value in dollars and widgets and accords so little to literature? How are writers made? And how is writing made? These were the prompts the Sydney Review of Books issued to all kinds of writers, to the essayists and critics who are frequent contributors to the journal, and to poets, novelists and experimental writers. We sought essays that charted writing as a form of creative labour, and found ourselves with a large and eclectic set of works that deliver new insights into the creation of Australian literature.

How writers get it done is a staple of festival Q&As and magazine profiles. There are no precious morning rituals here, however, no magic tricks for aspiring writers, and little in the way of idealism. These essays document writing lives defined as much by procrastination, distraction and economic precarity as by desire and imagination, by aesthetic and intellectual commitments. Labour is at the heart of this collection: creative labour, yes, but also the day jobs, side gigs, and care work that make space for writing. The public funding available to Australian writers continues to contract, the prospects of healthy royalties from book publication are dim, and the gigs on which so many relied to pay bills, workshops, teaching, public events, have diminished in number. There’s nothing in Open Secrets that conflicts with the regular reports from the Australian Society of Authors about the sinking financial returns of literary work. Many of the essays in this book, especially those authored during the Covid shutdowns in 2020 and 2021, are characterised by a discernible weariness.

Is it worth it? For readers, the work is the reward. As you’ll discover, these essays are funny and intelligent and they quiver with joy and determination. For the writers gathered in Open Secrets, however, the true worth of literary work is a complex question that generates often contradictory answers. Writers may work alone in their rooms, but they are also creatures of the world, and each contributor to Open Secrets thinks in surprising ways about literature; they attest to forms of value beyond the economic, to the social, political and aesthetic dimensions of literary practice. This book offers portholes into the places where writing happens and portals to the new worlds and ways of living it might create. These essays bear witness to the resilience required to commit to the writing life – and to the vital transformative possibilities of literature, for writers, for readers and our culture.

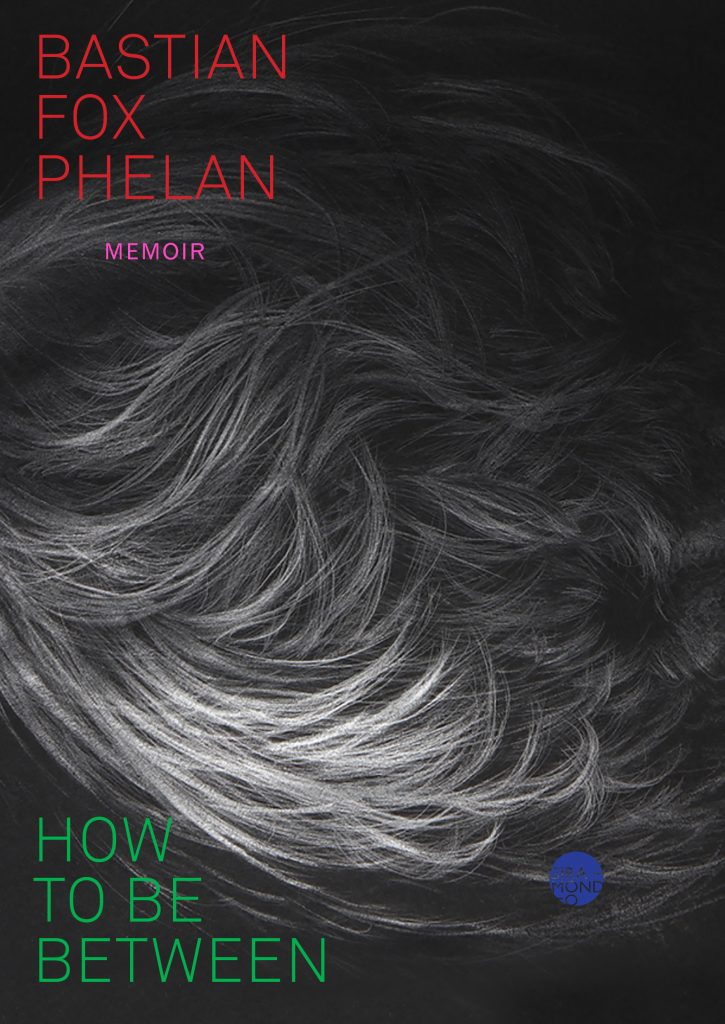

Bastian Fox Phelan: a note on How to Be Between

Bastian Fox Phelan reflects on How to Be Between (May 2022), their debut memoir.

I wrote How to Be Between because I had never read a story like mine. For a long time, I didn’t even know anyone who, like me, had the ability to grow facial hair as a female-assigned person. All I had were the narratives that had been imposed upon me – that female facial hair is aberrant, unsightly, shameful. That it should be hidden from sight and never spoken about. But I didn’t want to hide, and I didn’t see why I should feel bad about the way my body was.

This book has its origins in a zine called Ladybeard which I published in 2010 after growing out my facial hair for the first time. I knew I wanted to write more, but first I had to learn how to exist as a person who is visibly between sex and gender norms. My interactions with others showed me how deeply ingrained the gender binary is, and how people still seek to control how girls and women look. Although I had refused to accept invisibility and silence, these experiences often robbed me of my voice.

Writing allowed me to respond to the demands of a society that loves to categorise. From the first appearance of the hair in my early teens, and the need to survive high school, through multiple shifts in identity, friendships, family relationships, political activity, and artistic practice in my twenties, I have tried to find a way to articulate who I am. For me, writing has always been a bridge: between the self and others, between the material and the spiritual.

In writing How to Be Between I realised that my story was about much more than hair. It is about claiming an individual identity, and communicating this, but it is also about how we exist in relationship with others, always, and how precious these relationships are. Finding the balance is an ongoing project.

I worked on How to Be Between from my late twenties to my mid-thirties. For as long as I have been at work on this book, this book has been at work on me. Writing helped me accept my own fluid nature, and it gave me permission to continue changing and growing. I hope that reading this book brings comfort and joy to others who may sometimes feel that the world is not big enough to contain all that they are. And I hope it helps people engage with questions around gender norms, self-worth, and self-expression – questions that need to be asked, but don’t always need to be answered.

— Bastian Fox Phelan

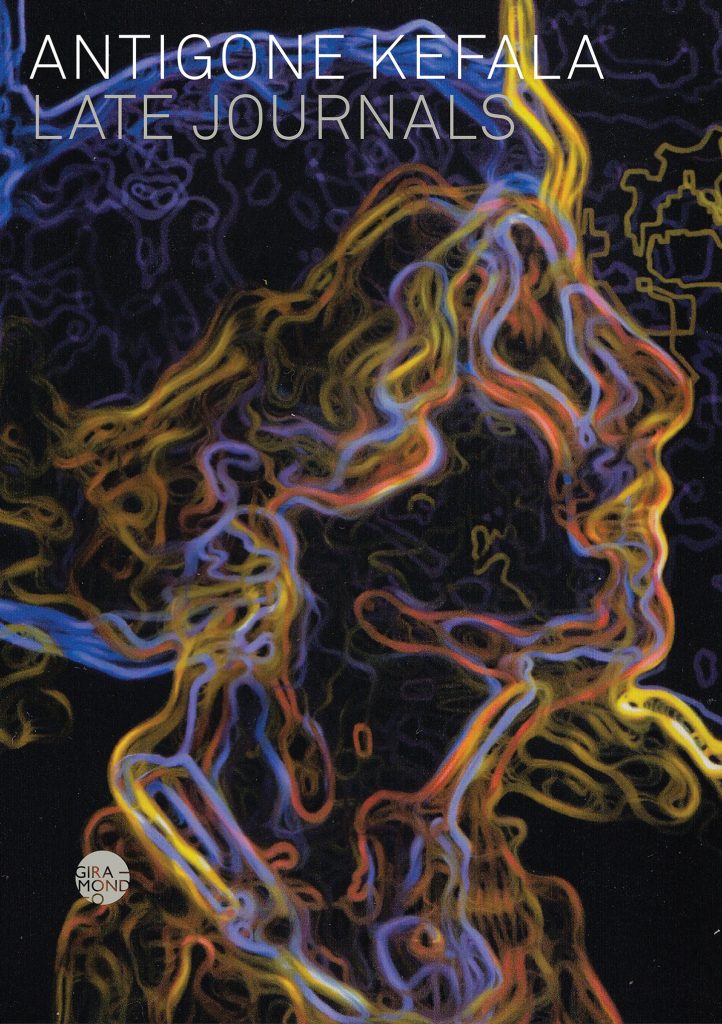

Publisher note: Late Journals by Antigone Kefala

The following note on Late Journals, written by Giramondo publisher Ivor Indyk, draws on a conversation between Indyk and Antigone Kefala that took place in January 2022.

The journal is an attractive and capacious literary form. As the term suggests, it is committed to recording the details of daily life, and Kefala’s Journals in particular display an extraordinary range in presenting her responses to the passing years, her deep sympathies with the lives of her friends, her intellectual interests in music, art, literature and film, and her keen awareness of the vitality and wonder of the natural world.

Kefala had been writing down her impressions from the period when her family was first displaced from Romania to Greece after WWII, but the physical journals which provide the raw materials for her published Journals date from the early 1970s (her first poetry collection, The Alien, was published in 1973, her first work of fiction, The First Journey, in 1975). In her words, ‘I always felt I was in a relative position [as a writer of migrant background in Australia] – writing became a way of making yourself more real, because you had to put it down, and you had to analyse it, and you had to bring the entire environment into it so that you could make some sort of assessment. We have gone through so many cultures, the Romanian, the Greek, the New Zealand, the Australian, the different languages, the different attitudes, landscapes, histories – you constantly had to adjust to all this, you had to find some sort of methodology that would allow you to deal with it in a much more natural way than making it into a major issue.’

The journal is different in this respect from a diary. ‘I think to a certain extent the diary would be something that goes directly onto paper without much stylistic consideration, while a journal you have to look at stylistically, especially if you are going to publish it, you have to see how it works for other people, while a diary is mostly for you. When I write in the journal, I write it as a piece of writing, constantly thinking of the form, but not to the extent that you would with a piece of fiction or a poem you were writing, something much more loose. The consciousness of it as writing is always there, and then afterwards there is the process of selecting and arranging the pieces in relation to each other, so that readers will understand what direction I am moving in, the remarks I am making.’ There is no specific time for recording the observations, ‘it could be a week or a month later, depending on what triggers it. I don’t write everything down, I write only things which I feel have some inner importance, because life is made of one hundred thousand things that you never write about.’

The published Journals are therefore carefully composed. Though each is structured according to a calendar year and divided into months, the impressions themselves may be drawn from different years – their ordering in the book is designed to create resonances and connections, and to enhance the expression of emotion.

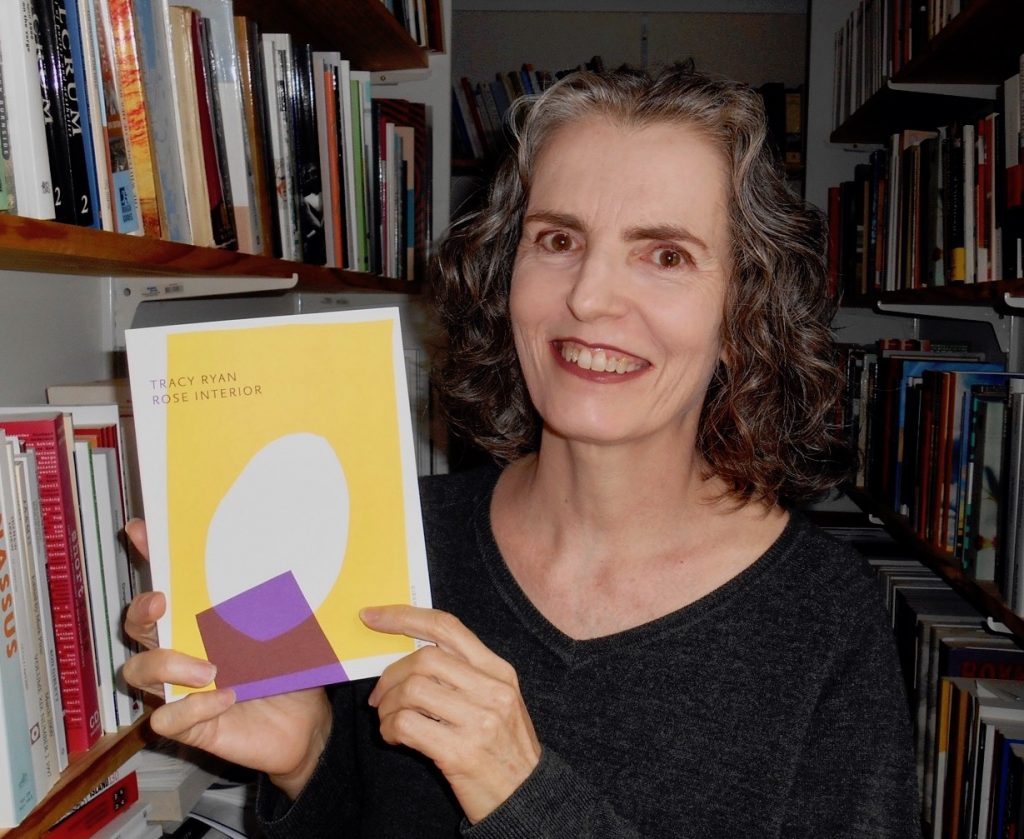

Tracy Ryan: a note on Rose Interior

Tracy Ryan reflects on Rose Interior (April 2022), her tenth full-length collection of poetry.

I’ve lived in many different places and houses, and many of the poems in Rose Interior focus on how you make a relationship with place. In recent years those places were Ireland and Switzerland, where I have distant yet strong family and emotional connections, and Australia. The poems look at all these from both inside and outside.

Sometimes the interiors are literal: hearing noises in a creaky house you’re just getting to know, or worrying about a leak in the ceiling. Those become images of psychological states. Sometimes they are symbolic: childhood memories, the mother-of-pearl on the inside of a shell my mother used for holding her jewellery. Or the knitting through which she created an outside to embody the inside of each child’s personality in a very big family.

Wherever home lies, it’s always on borrowed time – a house rented from strangers overseas, or the lease we seem to hold on our own lives. Our first home is the mother’s body; our individual space is always enmeshed with another person’s. We begin our lives connected, however isolated we might become, and several poems in this book dwell on the effects of the maternal bond, its duration and its apparent end, trying to find meaning in loss.

So the poems explore the domestic, but not only. Interiors suggest exteriors. This book is also about the outside world, its flora, including Rilke’s rose that provides the title, and its fauna real and imagined. How we interact with them – our care, or lack of care, for places and people – affects the way we grapple with global warming and other huge challenges. The last part of the book delves into schooling at home, as a kind of inside response to the outside. Warmth and safety, or unbearable confinement, stable or on shaky foundations – home is a word charged with contradictions on both sides, and that paradox for me makes poetry.

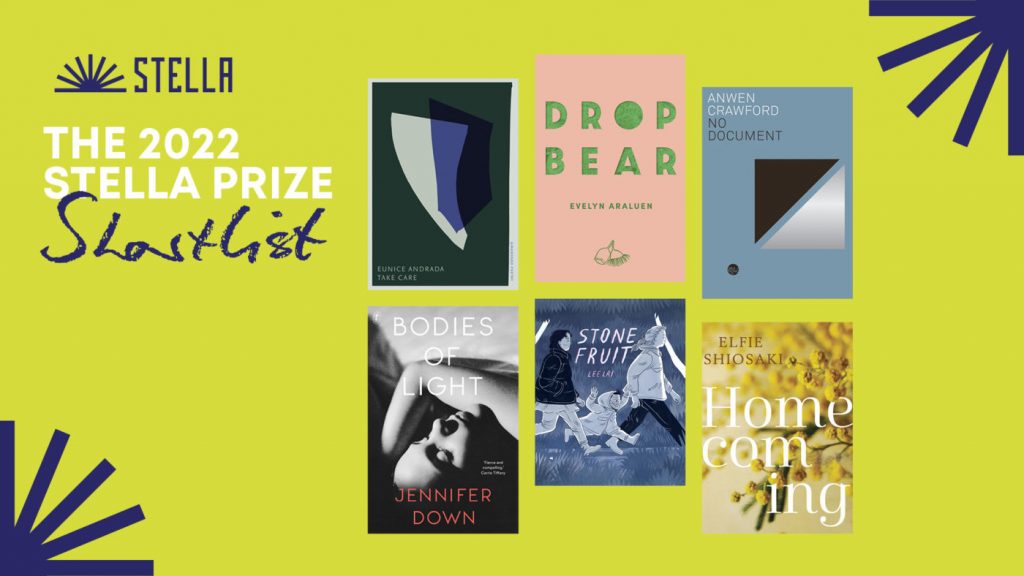

Eunice Andrada and Anwen Crawford shortlisted for The Stella Prize

Authors Eunice Andrada and Anwen Crawford have each had their works shortlisted for The Stella Prize.

In the first year that poetry has been eligible for the award, Andrada has been shortlisted for her collection, TAKE CARE. Bound in personal testimony, the poems in TAKE CARE situate the act of rape within the machinery of imperialism, where human and non-human bodies, lands, and waters are violated to uphold colonial powers.

Crawford has been shortlisted for No Document, a groundbreaking work of nonfiction, and an elegy for a friendship and artistic partnership cut short by death. First published in Australia in April 2021, the book will be published in the United States by Transit Books in June 2022.

Of the shortlist, this year’s judging panel chair Melissa Lucashenko says: ‘The 2022 Stella Prize shortlist is big on emerging voices writing in unconventional ways – from regions, positions, and literary forms that transcend the mainstream. These authors are writing back, insisting that ‘other’ lives – First Nations lives, poor women’s lives, queer lives, and Filipina lives – matter on the page just as they do in everyday affairs.’

Now in its tenth year, The Stella Prize is an annual literary prize that recognises and celebrates books from Australian women and non-binary writers.

Read the judges’ comments on the two shortlisted Giramondo works below.

Judges’ comments: TAKE CARE by Eunice Andrada

Eunice Andrada’s second poetry collection meditates on the ethics of care and the need to dismantle in order to recollect, to recover, and to create. Andrada is a master of final lines, and many of these poems – ‘Subtle Asian Traits’, ‘Duolingo’, ‘Pipeline Polyptych’ – conclude with memorably succinct and inspired turns, as in the sardonic humour of ‘Don’t you hate it when women’, which goes from ‘kill the herbs on the windowsill /devote their year’s salary to take-out’ to ‘kill the cop / the colonizer / the capitalist / living rent-free in their heads / demolish the altar built on their backs / without blame /walk away’.

Andrada’s collection adroitly combines the personal, the political, and the geopolitical, narrated by a voice that is at once hip, witty, and deeply serious. Andrada has the imaginative ability to move between the memories of poet-narrators, historical asides, reflections on the nature of race and feminism in Australia, and questions of colonisation both locally and in the Philippines. Formally remarkable, stylistically impressive, and often surprising, TAKE CARE is a collection that understands the ways in which ‘There are things we must kill / so we can live to celebrate.’

Judges’ comments: No Document by Anwen Crawford

No Document is a longform poetic essay that considers the ways we might use an experience of grief to continue living, creating, and reimagining the world we live in with greater compassion and honour.

Reflecting on the loss of a close friend, comrade, and creative collaborator, Crawford moves through time in search of a remembered momentum towards revolution. Deconstruction and creation exist side-by-side as the processes of artistic techniques are described in detail, as well as the successes and failures of collective action.

This work is a complex, deeply thought, and deeply felt ode to friendship and collaboration. There is the persistent feeling that through grief – remarkable and devastating – one is able to temporarily glimpse everything they need to know. Returning to something lost is full of sadness, futility, and frustration but also represents a fierce commitment to possibility. The emotional, paradoxical tumble of grief and hope represents a universal desire for meaningful change and No Document implores us to harness that desire collectively.

Find out more about The Stella Prize on their website.

Happy Stories, Mostly is longlisted for the International Booker Prize

Happy Stories, Mostly by Norman Erikson Pasaribu and translated by Tiffany Tsao has been longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2022.

The book, which is Pasaribu’s first work of fiction and his second book translated from Indonesian into English by Tsao, is one of thirteen books on the longlist.

The International Booker Prize is awarded annually for a single book, translated into English and published in the UK or Ireland. Happy Stories, Mostly was submitted by Tilted Axis Press, which published the UK edition in 2021.

On the Booker Prizes website, the book is described as a ‘powerful blend of science fiction, absurdism and alternative-historical realism that aims to destabilise the heteronormative world and expose its underlying rot.’

The longlist was announced on 10 March 2022. The shortlist of six will be announced on 7 April and the winners of the prize will be named on 26 May 2022.

A mostly happy chat about Happy Stories, Mostly

Norman Erikson Pasaribu: I wrote these stories in Indonesian mostly listening to music. Do you do your translation in a similar way?

Tiffany Tsao: I did the opposite and worked in a sound vacuum! Your stories have such rhythm, and whenever I tried to listen to music, it interfered too much, so I ended up not listening to any at all. Just repeating the words of your original to myself, then internalising the sound to make an English dubbing. What music did you listen to, Normie? A particular song for each story? I know you wrote some of these pieces a long time ago, so I don’t know if you remember. But then again, sound memories can be so strong.

NEP: Wow, I wonder now how it feels to write or translate with no other sounds except your mind. Music helps me to concentrate less on other things around me. I get distracted easily, as you already know, and music helps me focus on the mood of the story. I listened a lot to Joni Mitchell in writing the stories in this book. Also Batak pop songs from YouTube. Joni’s ‘Little Green’ is honestly the soundtrack for ‘So What’s Your Name , Sandra?’.

TT: Do you select the song for the story, or does the story select the song? Do you go through multiple songs before you find ‘the one’?

NEP: I select the first one randomly, and then let the shuffle decide. Did you translate each of the stories in one go? How do you partition your workload for the day, and balance it with your personal writing and other works?

TT: I always complete one story fully before moving on to the next. Each of your stories, even though there are running motifs and connections, are such creatures in and of themselves, deserving complete attention. And also, I am so bad at multitasking: I can’t work on a new thing properly if I haven’t finished what I am currently working on. I haven’t written very much of my own stuff during this pandemic. Life is so chaotic recently. No balance. But it made me really happy to have these stories to hang on to – a gently bobbing life raft. I could wake up on working days and look forward to translating the stories.

NEP: Good portions of these stories are about Batak people who live in Bekasi. We had that amazing Bekasi trip back in 2019. Did it ever help you in translating these stories, and do you still think of the pempek we had for lunch?

TT: It was really cool, Normie, to be able to experience your ‘hood with you. Translating brought back nice memories of visiting you. I think it helped make the people and places you write about more tangible, more vivid. And gosh, that pempek haunts my dreams. Pempek is one of the childhood foods I miss so, so much. We’ve talked about music, but what role does food play in your writing?

NEP: Food plays a big role in my fictional universe, Tiffy. It’s almost as if food helps create the memories that my characters hold most dear. In real life, I cook for people I love, as everyone does. I want them to remember me when I am in the best frame, which is when I eat. In my writing process, I sometimes use food to understand more the relationship between the characters in the book. I mean, meal time is probably the most integral part of a human life. An example: Sandra and her boy Bison – their relationship is defined by the street cotton candy she bought when she walked home after working the morning shift. The cotton candy is not just a metaphor for a mother’s love, but also a deep love from a single parent who works to support herself and her child, despite everything.

TT: This is true. Now I am also recalling how Tula takes Sebastian out for ice cream and makes him food. And when Meta, the girlfriend of the awful narrator in ‘The True Story of the Story of the Giant,’ sends nasi bungkus meals to the shattered narrator to support him through his grief. Food is such an immediate and physically nourishing way of showing we care. (Ironically I am answering this question while making lunch for my six-year-old who just finished school on Zoom.) But I also think of the scene in the airport in ‘The True Story’ where the narrator is flying back after his friend’s funeral, and he becomes obsessed with the taste of the McDonald’s cheeseburger he’s eating. Is it significant, his attitude toward food at this point?

NEP: It is. Food can be such a comfort, but it also might prevent us from dealing with our own grief. The narrator didn’t realise that he couldn’t process his loss of his close friend (and perhaps also the platonic love he unconsciously had for him) because he never processed his loss of his father. He was so untrained in grief-processing he ended up forcing himself to overanalyse the taste of junk food. I mean, all of those brimming emotions need to go somewhere.

TT: True. I definitely know KFC is a comfort food for me – and for the main character in ‘So What’s Your Name, Sandra?’ too it seems. She takes a trip to an unfamiliar place to recover from her grief and ends up eating a lot at the KFC.

NEP: Indonesians that I know have this strange ritual of cutting hair to cut off a streak of bad luck. Or to go to the beach and walk on the shallow salt water to drive off bad luck or bad spirit. I think somehow it is because we think the ocean is pure, even though in reality, in Jakarta, it was so dirty, all thanks to industrialisation and the way we live. In a way, Sandra went to Vietnam in that mentality. She wanted a place she never visited to heal her. A little story about KFC: I lived in Hanoi in 2017 with so much trauma on my bag. I loved Vietnamese food, but, at times, when my head was so rough, I kept finding myself ordering at a nearby KFC. Somehow, I feel now, I was so depressed that I just wanted something so familiar. KFC chicken defined my college times, as we students saw it as a luxury and we ate it once a week together. But we had such a good time. I imagined Mama Sandra felt the same.

TT: There are so many ways in which the emotions in the stories overflow, spill over (to use imagery from the stories) and take forms different from the original feeling. How it morphs not just into hunger, but anger for some characters. Or channelled (with irony) into ‘bouncing back and improving oneself’ in ‘A Young Poet’s Guide…’ Or just wanting to do something in the case of the retired nun of ‘Ad maiorem…’ Or snooping (‘Our Descendants…’) or stalking (‘Deep Brown, Verging on Black’). One of the lines I found most striking during the translation process was the one from ‘A Bedtime Story for Your Long Sleep’ – of ‘a bottomless pit of sorrow-bricks’ to build a ‘Babel Tower of misery’. I felt as if it captured how I’ve ended up approaching translating this collection. To be honest, I have felt so much sorrow during this translating time, for various reasons. And I felt somehow that, well, maybe there is hope if these bricks of sorrow can at least be used to create something – a tower that will lead out of the pit. I think it also held a mirror up to how I approach both my translation and writing work. I think there’s something almost superstitious about it, but I think I believe that the more of my heart I wring into it, the sweeter the resulting ‘juice’ will be. And it really felt like this when translating this collection. I don’t want to sound depressing or gloomy. I think it was more like…the transmutation of intense sorrow into melancholic joy?

Actually, I feel the original title of the collection captures this happiness-sorrow combo: ‘Cerita-cerita Bahagia, Hampir Seluruhnya’ could also be translated as ‘Happy Stories, Almost All of Them’. Could you tell us more about the ‘Hampir’ – the Almost? So many of the stories are about the heartbreak of ‘almost’ – either deep longings denied, or hopes crushed, or false notions shattered, or coming so close to happiness or actually experiencing it, only to have it ripped away.

NEP: One of the stories in the book was written based on the tale of Count Dracula. I grew up with countless Chinese vampire movies, and these B-movies have helped shape who I am as a storyteller. I also loved watching Coppola’s Dracula when I was a kid. And, to be honest, it was even more haunting to watch it on TV at midnight when your parents slept in the next room – their room didn’t have a door at that time. What if they woke up and caught you not sleeping, and instead watching the movie’s more erotic scenes?

The idea of using the word bahagia (happy) as a title of the book comes from a Goodreads reviewer who advised me to change the title of my first collection to ‘Stories of People in Suffering,’ a review that I found very funny. I mean, hetero readers hate sad-all-the-time fictional gays, but give zero effort to make us, who are gay in the flesh, happy. It’s a sad irony.

I decided to use the word ‘hampir’ because it is just a letter away from the word ‘vampir.’ Being happy, being contented, being positive, being productive, being on-top-of-the-world, being fearless, being be-yourself, and being unapologetic are often demanded of us by the so-called progressive heteros. Snap out of it, you poor gays, they might say. As sad it may sound: for them, happy gays are a sign of social progress. But, let’s be real: can you, as a queer, be happy in the way the heteros are happy in Indonesia? Happiness requires an endless list of privileges, in any part of the world. I mean, it is often the heteros that block us from accessing happiness. So I feel those words aren’t used with good responsibility. We queer are always thrown to the hampir, to the almost, and there the idea of happiness turns into the vampir.

On the other hand, I like to laugh. I like to complicate and challenge my sadness, like when you tear down the calm water just because you want to annoy the ducks. It is the way to cope for millions of people. I always hate it when I see Marvel movies trivialising traumatic events. And I hate the overwhelming heterosexualities in Disney movies. I think this book is also me approaching sad stories with a more humorous approach, while still respecting the feelings of my characters.

TT: One of the things I find so cool about your stories, and your work in general, is the extent to which queerness is woven through every aspect of your writing – the form and the imagery too, not just the subject matter. I feel, whenever I reread your works or discuss them with you, they are always yielding something new in this respect. I am always discovering a new queer feature of the stories.

NEP: Well, it’s probably because I like it when people read my work slowly (and slower). I am always a big re-reader myself. I mean, imported books are expensive. And I like the idea of finding something so different on the second or the third read. I feel, somehow, I had to live within a secret for so long that now I tend to build my writing with secret doors. For example, ‘Enkidu’ is a mini story about flooding in the area where I lived. For all my life, I always hated the rain because it is the time when my family is most vulnerable, but some of the most joyful childhood memories of mine were dancing in the rain, around the brown water that always seemed to try to swallow us all. But I always find ‘flood’ pretty queer. I mean, it is definitely not ’river’ or ‘sea’, but you can never call it ‘dry land.’ I wrote ‘Enkidu’ only after I thought the manuscript of this book was finished, after another flood happened during the 2019 New Year’s Eve. With the water reaching up to my hip that morning, I thought of the flood in Gilgamesh, and I thought of Enkidu, who was not female or male, and I thought of myself. So I decided to open my book with an environmental disaster…that I found pretty gay. And I want my readers to find these little things on their numerous re-readings. Layered stories, with their endless connections to other or older texts, work damn well with queer narratives. I mean, we need to invent our own new histories, because our own histories have often been erased, and fiction is just the way for that.

TT: The neither male nor female of Enkidu and sea nor land of floods makes me think of ‘Metaxu’ – the title of one of the stories, but also key to Simone Weil’s philosophy, which I know has influenced your work as a whole. ‘Metaxu’ – the Greek preposition meaning ‘between,’ which Weil uses to describe a connecting wall that serves as both barrier and means of communication.

NEP: I am always drawn to mysticism in general. When I was younger, my mom said that multiple generations ago one of my paternal ancestors was a tribal witch-something we never talked about openly due to Christianity. Stories of witch doctors, begu ganjang (hungry long-bodied ghosts), or even intergenerational curses filled my childhood, whispered among the adults. Just to be very clear: I didn’t grow up with secular philosophy on my plate. I grew up with the Bible and outdated lifestyle magazines and newspapers that my dad hoarded because he was a reporter. Simone Weil’s philosophy spoke to me because of her lifetime interest in rejecting power, any form of it. I found a quote of hers in the opening of Mary Szybist’s Incarnadine, my favourite book of poems. After that, when I was traveling, I bought Gravity and Grace, and I was quickly struck by the idea that grace can only fill empty spaces. There is something vulnerable and honest in that, I think, and I was drawn to it.

TT: And yet, God is profoundly and heartbreakingly absent in the stories. Absent from the life of the nun who devoted her whole life to him. Even the admin staff of heaven have never seen him. The only time we see God for real, it feels, is in the story that ends ‘The True Story of the Story of the Giant‘.

NEP: Talking about religion today is very difficult. Partly because I feel our relationships with religions and divinities have been smeared by how colonialism badly shaped our lives. And queer people’s relation with the divine is, of course, sabotaged by the heteros. Pramoedya Ananta Toer once spoke about an internal resistance, a resistance that happens inside us even when we’re silenced and have no way to fight. I like to think I channel my internal resistance through writing these stories.

TT: A less deep question – about the title, ‘Three Love You, Four Despise You’. I’m curious about where it came from!

NEP: My Indonesian editor Mirna asked a similar question before. She thought it was a cool title, and wondered how I came up with it. Ha ha! It’s actually the size of a typical kos room here: 3 x 4 meters. I mean, the story is about a queer person trying so hard to be a free person, but always ending up on the ‘almost’: he’s confined by his own ‘modernity’, his own away-from-parents-ness, his financial situation, the heteronormative world he is living in, his desperate love for the divine, and, yeah, his own room. Also, sometimes I feel titles in general are a bit like confinement too. Titles give a name or even identity to a narrative, but also contain it, as they often bring expectations to what the story will tell, silently erasing some possibilities. So, what if I apply a confinement (3 x 4 room) to a confinement (title)?

TT: The kos is just one recurring element of many throughout the collection: The mother characters who love their gay sons but then ruin their lives. Rotting teeth. The pupils of eyes. Lonely people longing to find that one other special person. Chocolate. Even names: Anton, Laura, Leo, Lin.

NEP: All the stories in the book are interconnected, in ways that might not be apparent on skim reading. I once found an English ‘larger than the sum of its parts,’ and I feel this phrase is practically how I write. Sometimes, for names, I picked it because it was the name of a character in my other work. ‘Laura’ is a name in a sci-fi novel that I never finished, Paralaura (Para is, of course, short for parallel, but in Indonesian ‘para Laura’ means a group of Laura, or the Lamas.) It’s like a Groundhog Day novel, but the Phil Connors in the story is a cranky older Batak woman. I borrowed Laura from that never will-be novel, and put it in another story. I like the idea of a revisable universe. I also like to play with names, I guess. The Sandra in ‘So What’s Your Name, Sandra?’ is actually from the word ‘sandera’ (hostage) because one of the recurring topics in these books is how we are dictated by our memories.

TT: Memories seem to open up such parallel worlds for so many of the characters – glimpses of alternate histories and lives they might have had. Not just memories in their heads, but memories in the form of photos as well – like postcards from another life. It makes me think of a phrase that I often hear and read you say: ‘discontinued futures’. Is there some other universe in which these stories are Happy Stories without the ‘almost’, the ‘hampir’?

NEP: Of course, there are! I am obsessed with the idea of re-creation. I have a never-published story about the girlfriend of Leo and Thomas’s son from ‘Our Descendants’. Another example is Tula, the nun in ‘Ad maiorem dei gloriam’ who, in another story that is set in the future, is a general in an intergalactic war between this galaxy’s God (who owns the office Heaven in ‘Division of Unanswered Prayers’) with an alien God from another galaxy. I just haven’t published these stories because I often feel insecure with the styles of my older writing. Maybe one day I will finally find my magical crispy chicken that will give me the energy I need to finish all of my work-in-progress. I mean, who knows?

The above conversation between author Norman Erikson Pasaribu and translator Tiffany Tsao was printed in the Tilted Axis Press edition of Happy Stories, Mostly (2021, UK), and is republished here with permission. The Australian edition of Happy Stories, Mostly was published in March 2022, and was longlisted for the International Booker Prize in the same month.

Norman Erikson Pasaribu and Tiffany Tsao: notes on Happy Stories, Mostly

The Indonesian title of this book is Cerita-cerita Bahagia, Hampir Seluruhnya. The idea of using bahagia (happy) as a title of the book comes from an online review that advised me to change the title of my first collection to ‘Stories of People in Suffering’, a review that I found very funny.

Hetero readers hate sad-all-the-time fictional gays, but often put in zero effort to make us, who are gay in flesh, happy. It’s a sad irony.

A story in this book was based on the tale of Count Dracula – where it was turned queer, Batak, Indonesian. And the word ‘hampir’ made itself into the title because it’s just a letter away from the word ‘vampir’. Being happy, being contented, being positive, being productive, being on-top- of-the-world, being fearless, being be-yourself, and being unapologetic are often demanded of us by the so-called progressive heteros. As sad as it may sound: for them, happy gays are a sign of social progress. But, let’s be real: can you, as a queer, be happy in the way the heteros are happy in Indonesia? Happiness requires an endless list of privileges, in any part of the world. It is often the heteros that block us from accessing happiness. We queer are always thrown to the hampir, to the almost, and there the idea of happiness turns into the vampir.

– Norman Erikson Pasaribu, author

After Norman and I worked together on my translation of his poetry collection Sergius Seeks Bacchus, there was no question about whether I would translate his prose. I had become such an avid fan of Norman’s writing, and we had struck up such a wonderful friendship and working relationship, that it was the obvious next step. I’d assumed that I would be translating his first short story collection, but Norman told me that he was working on a new one. He would send me individual stories to translate after he had revised and reviewed them. They were superb tender gems, arriving in my inbox one by one, until finally, there was a whole manuscript ready for me to read. Each story had been so unique, so distinctive, that I hadn’t anticipated how marvellously they would come together as parts of a whole. Even now, several months after completing the translation and many re-readings later, it is difficult for me to open the book and read part of a story – I end up reading the whole story, then the following story or the preceding story, and what was meant to be a brief consultation of the work ends up ballooning into a happy revisiting of the entire collection. I hope you will enjoy these stories as much as I have, and read them as I have translated them: from the heart.

– Tiffany Tsao, translator

Claire Potter: a note on Acanthus

Mais toujours et distinctivement je vois aussi La tache noire dans l’image…

Yves Bonnefoy

For a long time a plant in my garden flowered beneath the hydrangea, spilling bright green leaves. I would cut the leaves back as soon as they arrived as they crowded and swamped the path. As much as the plant was reduced, it would spring back to life. After a while, I began to admire this persistence and discovered the plant was an Acanthus. The plant did not appear in my writing until, by chance, I came across a story that linked it to the stone carvings of flowers and leaves that often ornament architectural columns. Trees, leaves and stones were already in my writing so it seemed like a good idea to name the collection after a plant that despite effacement, did not want to go away.

An enduring line running through Acanthus is perhaps one that inevitably moves obliquely or sideways. Looking back now, many of the poems traverse the clarity of a dream-like state: diverting from an imaginary centre and meandering across strange ground. As with all poetry, fragments matter; figures and objects – as if on the level of the bee – are significant; unintelligible feelings turn into a blueprint language that errs and wanders in order to find a resting place.

Nothing in the collection was fixed beforehand, you could say the writing took place in order to think a way through, think about certain things or events that at the time didn’t have any formal presence in my mind. The central question of the collection could be this inclination towards remembrance; a leaning inwards that – like Icarus – mirrors a leaning outwards, an imperfect zigzag between the reality of a leaf and its allegorical translation into stone.

If there is a context to the collection, then it would be a porous one involving authors I read; in many ways their work makes up the true sense of the writing. The untitled preface is a nod in this direction, to where on the edges something occurs almost out of the corner of one’s eye like an annotation; this insignificance is precious and full of life. As William Carlos Williams said of Marianne Moore, ‘There must be edges’ and I think that these edges, very important to architecture as well, are such interesting places and form a touchstone for this collection; they are like a photograph, albeit on the negative side, where unexplained and forgotten things again find place, become clear and therefore on paper begin to happen.

– Claire Potter

Eunice Andrada and Anwen Crawford longlisted for The Stella Prize

Authors Eunice Andrada and Anwen Crawford have each had their books longlisted for The Stella Prize.

In the first year that poetry has been eligible for the award, Andrada has been longlisted for her collection, TAKE CARE. Bound in personal testimony, the poems in TAKE CARE situate the act of rape within the machinery of imperialism, where human and non-human bodies, lands, and waters are violated to uphold colonial powers.

Crawford has been longlisted for No Document, a groundbreaking work of nonfiction, and an elegy for a friendship and artistic partnership cut short by death. First published in Australia in April 2021, the book will be published in the United States by Transit Books in June 2022.

Now in its tenth year, The Stella Prize is an annual literary prize that recognises and celebrates Australian women’s writing.

Read the judges’ comments on the two longlisted Giramondo books below.

Judges’ comments: TAKE CARE by Eunice Andrada

Eunice Andrada’s second poetry collection meditates on the ethics of care and the need to dismantle in order to recollect, to recover, and to create. Andrada is a master of final lines, and many of these poems – ‘Subtle Asian Traits’, ‘Duolingo’, ‘Pipeline Polyptych’ – conclude with memorably succinct and inspired turns, as in the sardonic humour of ‘Don’t you hate it when women’, which goes from ‘kill the herbs on the windowsill /devote their year’s salary to take-out’ to ‘kill the cop / the colonizer / the capitalist / living rent-free in their heads / demolish the altar built on their backs / without blame /walk away’.

Andrada’s collection adroitly combines the personal, the political, and the geopolitical, narrated by a voice that is at once hip, witty, and deeply serious. Andrada has the imaginative ability to move between the memories of poet-narrators, historical asides, reflections on the nature of race and feminism in Australia, and questions of colonisation both locally and in the Philippines. Formally remarkable, stylistically impressive, and often surprising, TAKE CARE is a collection that understands the ways in which ‘There are things we must kill / so we can live to celebrate.’

Judges’ comments: No Document by Anwen Crawford

No Document is a longform poetic essay that considers the ways we might use an experience of grief to continue living, creating, and reimagining the world we live in with greater compassion and honour.

Reflecting on the loss of a close friend, comrade, and creative collaborator, Crawford moves through time in search of a remembered momentum towards revolution. Deconstruction and creation exist side-by-side as the processes of artistic techniques are described in detail, as well as the successes and failures of collective action.

This work is a complex, deeply thought, and deeply felt ode to friendship and collaboration. There is the persistent feeling that through grief – remarkable and devastating – one is able to temporarily glimpse everything they need to know. Returning to something lost is full of sadness, futility, and frustration but also represents a fierce commitment to possibility. The emotional, paradoxical tumble of grief and hope represents a universal desire for meaningful change and No Document implores us to harness that desire collectively.

Find out more about The Stella Prize on their website.

The Novel Prize: entries opening 1 April

Giramondo Publishing, Fitzcarraldo Editions and New Directions are pleased to announce that The Novel Prize, the biennial award for a book-length work of literary fiction written in English by published and unpublished writers around the world, will open for entries for submissions on 1 April 2022.

The Novel Prize offers US$10,000 to the winner and simultaneous publication of their novel in Australia and New Zealand by Sydney publisher Giramondo, in the UK and Ireland by the London-based Fitzcarraldo Editions, and in North America by New York’s New Directions. The prize recognises works which explore and expand the possibilities of the form, and are innovative and imaginative in style.

The inaugural winner of The Novel Prize was Cold Enough for Snow by Jessica Au, which was selected from over 1500 entries worldwide. Cold Enough for Snow was published in Australia, the UK and the US in February 2022, and is set to be published in eighteen territories. Jessica Au said: ‘The Novel Prize has been an incredible experience – to have had the opportunity to work with publishers of the calibre of Fitzcarraldo Editions, Giramondo Publishing and New Directions, and for Cold Enough for Snow to be translated internationally from there, is something I will continue to be both amazed by and grateful for.’

The Novel Prize is managed by the three publishers working in collaboration. Entries will be open from 1 April to 1 June 2022, with Giramondo reading submissions from Asia and Australasia, Fitzcarraldo Editions from Africa and Europe, and New Directions from the Americas. A shortlist will be made public in December 2022, with the winner announced in February 2023. The winning novel will be published in early 2024.

For more information please visit www.thenovelprize.com.

Praise for The Dancer

It’s an extraordinary book and it just got under my skin and has filled my mind. It’s a book about my generation and the damage done so there’s a lot to recognise and it’s a book that keeps faith, with Philippa Cullen and the dance of life against the odds…The cascade of Philippa’s relationships…is awesome in every way…It is a book about Australia and our impossible relationship with the outside world…the changes that reached for the outer limits in the 70s.

Nicholas Jose

I adored The Dancer…it was absolutely the perfect reading for the tail end of the long lockdown – so transportative, it felt like I was actually going places, when I hadn’t left the house for months, and still didn’t quite have the option to! Loved the daring of the first 100 pages too, and now wish more biographies took the long view of a life.

Sam Twyford-Moore

This book is enlivening in every, extraordinary way. I want to live inside it like one of the leaves Philippa Cullen pressed between the pages of the books she read; her own and the ones she borrowed from other people.

Anna MacDonald

I finished The Dancer yesterday and am sad, for two reasons: one, because it’s been my companion during two weeks of camping and now it’s finished, and two, because Cullen’s vibrant life was cut so short. I had a bit of a cry towards the end…I really loved the book.

Tom Carment

A biography for, not of…And as always with Juers, an evocation of something more than a single life, or period, or place: events, characters, phenomena that might at first seem incidental but belong to a complexity and rich interconnection of things that she is fascinated by and which we, as readers, are seduced into finding equally relevant and illuminating.

David Malouf

I’ve plunged into The Dancer and it’s got a wonderful grip on me…I’ve never read anything quite like it. It’s one of those rare books that become an alternative world while you’re reading it… I keep thinking of…the lists of her daily tasks and duties – this moved me…the dense texture of her existence as both an artist and as an ordinary woman with friends and family she loved – how it was made up of great strokes of ambition and imagination and drama and LABOUR and at the same time of tiny, faithful, reliable, seemingly inconsequential quotidian details.

Helen Garner