Uncategorized

Autumn Royal’s launch speech for Naag Mountain by Manisha Anjali

Naag Mountain by Manisha Anjali was launched in April 2024 at The Alderman in Brunswick East during a sold-out evening event. The event featured a speech by poet Autumn Royal in honour of releasing Manisha’s debut book into the world. The speech was followed by a haunting and transcendental vocal and harp performance by Genevieve Fry. Read a transcript of Royal’s speech below.

The following speech was delivered on the unceded lands of the Wurundjeri Woi-Wurrung people of the Kulin Nation. We acknowledge and respect their Elders, both past and present. We extend this respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals who may read this speech. Always was, always will be Aboriginal land. We also wish to express that from the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.

I first physically met Manisha in a garden. It was 2019 and we were reading alongside each other at a house fundraiser for the Djab Wurrung Heritage Protection Embassy. But I do not doubt our spirits already knew each other intimately as years earlier, Manisha’s stunning poetry gushed into my psyche, and I was enraptured and now – I am here.

At this point, it feels necessary to summon (or depend upon) the words of the brilliant Eunice Andrada when she expresses that Manisha’s ‘Naag Mountain is an exquisite work that resounds with the reminder of what can be reclaimed when a community moves towards their awakening: their dreams, their futures. This is a distinguished debut collection from a poet whose vision is urgent and consuming.’

‘Urgent and consuming’. I respectfully echo Andrada’s words as I attempt to form an articulation of Manisha’s Naag Mountain and the significance of its existence. Speaking about this book in front of you, dear audience, is a privilege and beyond this scripted reading, I promise to consider how I can ever return such a deep honour.

As Manisha explains in her author note to accompany this work of brilliance: ‘Naag Mountain is the recovery and aftermath of the girmit, the period between 1879 and 1916 when Indians [derogatorily termed ‘coolies’] were taken to Fiji for indentured labour on Australian-owned sugar cane plantations’. Manisha’s Naag Mountain potently and generously illuminates the realities of the cultural and cellular inheritance of this indentured labour through a collaboration of dreams, oceans, archival documents, songs, ancestral historiographies, and poetry.

Naag Mountain also reveals a complex and intertwined circuitous narrative spanning across times, oceans, and realms. Within Naag Mountain, there exists an imaginary film called ‘Paradise‘. As Manisha eloquently describes this film within the text:

In this film, the actors are allowed to walk away – to reject their scripted roles and embrace their continuous evolution of identities between human and non-human beings. The existence of the film, ‘Paradise’, allows for such action. The poetry surrounding this film, ‘Paradise’, also generates an action, but without containment. As Naag Mountain declares, nothing should ever be contained.

‘Paradise’ correspondingly brings awareness to the concept of ‘depiction’, and the deplorable truth that this film, this narrative of ‘Paradise’, should already be known and that these actors should have always had agency and dignity.

I quote another passage from Naag Mountain where such agency and dignity are allowed, encouraged, and guided by spirits across oceans in a moment where the actors:

Naag Mountain is an epic poem in which the concept of the ‘single and distinctive hero’ is not just overturned by Manisha’s captivating poetic voice and defiantly vivid expressions, but completely quashed. This is not done out of spite or in a cruel manner – but through a multitude of polyvocal voices, bodies, entities, spirits, animals, elements, and sensations that challenge the notion that there can only be one dominant account of history. As Manisha’s expressive voice guides me over the phone: ‘The Indo-Fijian psyche does not just inhabit the physical realm’.

Radical metamorphic bodily changes occur throughout Naag Mountain during violent scenes and traumatic events, but most significantly, these transformations also take place throughout moments of deep love and celebration. There is also the metamorphosis of yourself as a reader – something that is so very crucial and so very sacred. As Nancy Gray Diaz elucidates, metamorphosis ‘represents the conjunction of self and world, and it plays out the individual’s conflict with, or assumption into, the values of that world’.

Interconnected with metamorphosis is a meaningful and poignant theme in this book is the birth and rebirth as ‘Paper jackal fly out of my mouth, and / into the misty air, and into the monsoon’ (p. 8).

With such lines, both birth and rebirth are intricately woven and profoundly expanded upon throughout the entirety of Naag Mountain with keen attention and generous dedication.

In this work, in Naag Mountain, all matters expressed are actualities and are not merely metaphorical representations. Here, in Naag Mountain, ‘metaphor’ as a concept is considered too simplistic and detached for such a profound understanding of what is occurring. In Manisha’s own words: ‘through the process / of extraction, I see my responsibility. It is standing still at / the top of the mountain (p. 31). There is a view from the top of the mountain and Manisha is showing it to you, dear reader.

At this point in my scripted act, I have exceeded over 300 words. Three – the number ‘3’ – and the time of 3 a.m. is extremely poignant and forceful in the actuality of this work and the history it is based upon. This is the time when ‘the coolies’ were ordered to rise from their dreams and begin work. It is also known as ‘the suicide hour’, a bodily sacrifice often performed as an act of resistance against ‘the company’ that once ‘owned’ Manisha’s family. The Colonial Sugar Refining Company.

I will end/open with Manisha’s evocative and powerful description of ‘this company’:

Alexis Wright and Sanya Rushdi shortlisted for The Stella Prize

Two Giramondo authors are shortlisted for the 2024 Stella Prize: Alexis Wright for her epic novel Praiseworthy, and Sanya Rushdi for her autofictional work, Hospital. The announcement was made on 4 April on ABC Radio National.

Six books are shortlisted for the $60,000 prize for Australian women’s writing, which is awarded annually ‘to one outstanding book deemed to be original, excellent, and engaging’.

‘A canon-crushing Australian novel for the ages’, Wright’s Praiseworthy has won the Queensland Literary Award for Fiction, and is currently shortlisted for the Dublin Literary Award and The James Tait Black Prize. Rushdi’s Hospital, translated from Bengali by Arunava Sinha and described by the judges as ‘deeply experiential’, is the author’s debut book.

Judges’ comments, Praiseworthy:

Fierce and gloriously funny, Praiseworthy is a genre-defiant epic of climate catastrophe proportions. Part manifesto, part indictment, Alexis Wright’s real-life frustration at the indignities of the Anthropocene stalk the pages of this, her fourth novel.

That frustration is embodied by a methane-like haze over the once-tidy town of Praiseworthy. The haze catalyses the quest of protagonist Cause Man Steel. His search for a platinum donkey, muse for a donkey-transport business, is part of a farcical get-rich-quick scheme to capitalise on the new era of heat. Cause seeks deliverance for himself and his people to the blue-sky country of economic freedom.

Praiseworthy walks the same Country as companion novel, Carpentaria, published in 2006, and here, Wright demonstrates further mastery of form. Reflecting the landscape of the Queensland Gulf Country where the tale unfolds, Wright’s voice is operatic in intensity. Wright’s use of language and imagery is poetic and expansive, creating an immersive blak multiverse. Readers will be buoyed by Praiseworthy’s aesthetic and technical quality; and winded by the tempestuous pace of Wright’s political satire.

Praiseworthy belies its elegy-like form to stand firm in the author’s Waanyi worldview and remind us that this is not the end times for that or any Country. Instead it asks, which way my people? Which way humanity?

Judges’ comments, Hospital:

Hospital is an unflinching, insightful and delicately wrought work of autofiction that brings devastating lucidity to the often-opaque realm of mental health. Drawn from Rushdi’s own experience with psychosis, it is a novel that bucks the classic tropes and cliches, eschewing sensationalism and sentimentality in favour of an invitation to meaningful engagement and understanding. Through her spare, honest words, deftly translated from the Bengali by Arunava Singha, Rushdi’s ordeal becomes our own. We descend into psychosis with the narrator, acutely feel her disconnections and institutional indignities. We come to question notions of “illness” and “treatment”. There are no jump scares, just the ineluctable clarity that demands we remain in the moment with something we find deeply uncomfortable.

The winner of the 2024 Stella Prize will be announced on 2 May.

An excerpt from Manisha Anjali’s Naag Mountain

The following excerpt is from Naag Mountain, Manisha Anjali’s remarkable debut collection. Anjali is an Australian and New Zealand poet of Indo-Fijian background, the descendant of indentured labourers. Her book is an imagined recovery of the little-known cultural inheritance of a displaced and exploited people.

The film that emerges from the waves in our place of conception, Port Douglas, Far North Queensland, is misty and blue-green. The reel is entangled symbiotically with kelp, sea lettuce and jellyfish. The film stock is full of salt and coral. Images imprinted on plastic film are visible through fragments of algae, sand and micro-civilisations of the sea.

When the two moons are released from shadow, we unravel the living reel and project the propaganda onto the sky. When we hear the ringing of temple bells, we hear songs that have been backmasked. When we hear the singing of conch shells, we hear songs that have travelled generations to be heard.

We are actors in an obscure, banned film called Paradise. Paradise is comprised of footage of the girmit, the haunted ‘agreement’, the Indian indentured labour system which was established after slavery was abolished. We sign contracts we cannot read, then we wipe the bloods from our brows with our eight hands, then we plant our eight hands into the lungs of the South Pacific.

—

Opening scene. Sugar cane plantation on fire. Tea plantation on fire. Copra plantation on fire. Banana, banana. Copra, copra. Fire. Fire wails with choirs of widows and seabirds: girmit songs of longing, mourning cries and culling prayers.

A circle of flames in the ganna field. In the middle is a white horse named Pajero, eating yellow wildflowers. Next to Pajero is Pilgrim with two black braids bound with red ribbons, a gold nose ring, white blouse and white petticoat. Pilgrim has a white chicken in one hand, and a mirror in the other. In the mirror is the reflection of the blue sea.

—

Things we carried on the Leonidas, 1879: our ganja, our nose rings, our holy water from the mouths of our rivers.

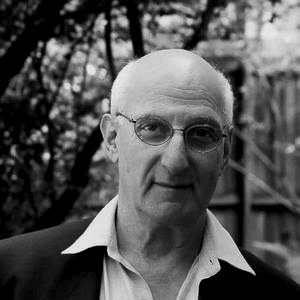

Celebrating David Malouf at 90

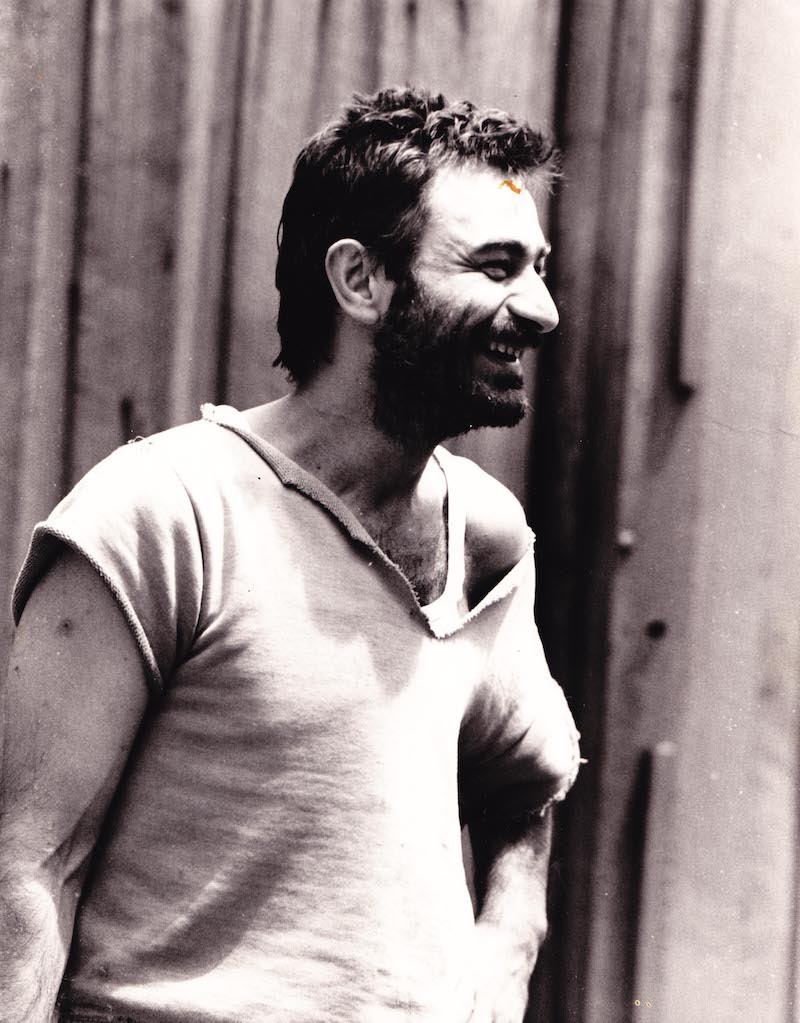

‘The most striking aspect of David Malouf’s life in letters is the multiplicity of forms it has taken, as if one should talk of his lives in letters rather than think of it as a single life,’ wrote Giramondo publisher Ivor Indyk in the Sydney Review of Books in honour of the author’s eightieth birthday in 2014. This March, Malouf turns ninety. We celebrate one of Australia’s best-loved writers and a long-time supporter of Giramondo, with a recorded interview, Malouf’s contributions to HEAT, and a poetic tribute from Nicholas Jose.

The photograph above captured David Malouf at the very beginning of his career, just ahead of the publication of his debut poetry collection. Sally McInerney, the photographer, said of that day: ‘David’s book of poems, Bicycle, was soon to appear, and the publishers had requested a suitable “author” photograph. So, in the summer of January 1970, we wandered rather shyly through the University of Sydney’s semi-deserted grounds, looking for places and light that would lend themselves to portraiture. We have been friends ever since.’

In conversation with Ivor Indyk

In a recording made in April 2021, Giramondo publisher Ivor Indyk spoke with David Malouf about his body of work as a poet and novelist, the time he spent away from Australia in Italy, his international reputation, and the imaginative power of his writing. Listen to their conversation below.

Giramondo Talks: David Malouf in conversation with Ivor Indyk

David Malouf in HEAT

David Malouf has been an important contributor to HEAT, Australia’s international literary magazine, founded by Giramondo in 1996. We feature below five contributions by Malouf, recently digitised in the HEAT archive. The sixth piece is a poem by Nicholas Jose, published in the very first issue of HEAT in honour of Malouf’s sixtieth birthday.

Epimetheus, or The Spirit of Reflection

‘We have all heard of Prometheus, great rebel against the gods and bringer to earth of a commodity, fire, which we have depended on from earliest times for much of what makes us human: campfires, cooked meat, the forging of iron into ploughshares, horseshoes, swords. What is not so well known is that Prometheus had a brother, also a titan and demi-god, but as his name suggests quite opposite in nature and habit of thought.’

Buxtehude’s Daughter

‘What she found most insufferable was the camaraderie between them, which she could not help but feel was an alliance; that and the assumption, in their careless all-conquering manner, that the world was theirs by right, to be divided up just as they pleased. Well, not if she could help it!’

Mozart to da Ponte: Words and Music

‘Words act, they get things going, they are sociable. They form unions, found cities, make contracts in which responsibilities are established and dues paid, or they break them and start wars. A sentence is a theatre in which something happens, it is all agents and events. But music is just itself. It has no story to tell, no truth to utter, and it cannot lie because it proclaims nothing but its own perfect presence.’

Ulysses, or the Scent of the Fox

‘The Greek commanders, Nestor, Agamemnon and the rest, could do nothing but wait, unheroically, for the cloud to lift from their champion’s brow. Till it did, they dared not move.’

The South

‘On a soft, sunlit morning in March 1959, just a few days before my twenty-fifth birthday, I stood at the rails of an Italian liner, the Fairsky, and after a five-weeks sea-voyage that had taken me via Singapore, Colombo, Bombay, Aden and Port Said, saw the Bay of Naples open before me, and utterly familiar in the distance the dark slopes and scooped-out cone of Vesuvius – all just as I had always imaged it, like the breaking of a dream.’

Moonflowers

By Nicholas Jose

‘Inside meantime, past sixty, you hold forth, tossing pasta and greens, searing the fish, uncorking wine, adjusting the lights, sentence by sentence giving shape and grace, enthusiasm, optimism, critique — all the while you are out there in the dark…‘

Grace Yee wins 2024 Victorian Prize for Literature for Chinese Fish

Melbourne-based poet Grace Yee has won the 2024 Victorian Prize for Literature, Australia’s most generous writing prize worth $100,000, for her verse novel and debut book, Chinese Fish. The surprise announcement was made at the Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards ceremony at The Wheeler Centre in Melbourne, during which Yee was also awarded the VPLA for Poetry, worth $25,000.

It was an exceptional day of recognition for Yee and her book, which was longlisted for the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards in the poetry category earlier that morning. Yee holds dual citizenship in Australia and New Zealand, with Chinese Fish distributed on both sides of the pond.

A polyphonic, multi-generational and feminist tale which tells the story of a migrant family in Aotearoa New Zealand, Chinese Fish began as a PhD thesis. ‘I wrote it for myself,’ said Yee. ‘I had absolutely no ambitions for publishing it…[and] when I finished my thesis, it sat in the top drawer.’ You can hear Yee talk more on her book in her interview with Mel Fulton on Triple R’s Literati Glitterati, which aired a few months after Chinese Fish was published.

This is the second year in a row that a Giramondo author has taken away the Victorian Prize for Literature, with Jessica Au winning it in 2023 with her novel, Cold Enough for Snow.

Read Yee’s acceptance speech for the Victorian Prize for Literature and the VPLA judges’ comments on her book below. A transcript of Yee’s Poetry prize acceptance speech can also be found on her website.

Grace Yee’s VPLA acceptance speech

If my parents were here, they would be gobsmacked. They would be astonished that this little story that I wrote even got published in the first place. This story, which was inspired by very ordinary people like them, to have been acknowledged like this is mind-blowing.

One of the things that has pleased me a great deal since I published the book, which I did not anticipate, is so many readers have reached out to me and told me how much this story has resonated with their own family stories of immigration and resettlement.

I think that literature is crucial for illuminating the ordinary. Ordinary people’s lives. Lives that have been marginalised, hidden, and erased. And for shining light on the darker recesses of the world. Literature raises really big questions and it has no easy answers. It gives us pause and I think those pauses are significant, more significant, when you read a story and the characters in that story, their lives are so very different to your own. That kind of literature gives us the biggest pause.

This award will enable me to have a bit of a pause and reflection. Which doesn’t mean that I’m not going to be doing anything! [laughter] Pausing and reflecting is as much of the writing process as putting pen to paper and putting words on a screen, as all writers know.

I am so very very grateful for this award, it is such an amazing honour. Thank you.

Watch the livestream of Grace Yee’s acceptance speech here.

Judges’ comments

Chinese Fish switches between lyric, dramatic and documentary poetic forms, to tell a multi-generational tale of the Chin family’s migration from Hong Kong to Aotearoa New Zealand. Yee focuses on women’s experience; particularly, how migration tests the relationship between a mother and her daughter. She tells this story with sparkling humour, wit, and stylistic verve, while paying sustained attention to historical circumstance – particularly everyday racism and the discriminatory government policies which affected Chinese migrants. Characters’ voices are interwoven with archival text and scholarly observations. Cantonese-Taishanese characters, peppered throughout the dialogue, enhance a reader’s connection to this fictive family and their past. We were impressed by how intelligently Chinese Fish braids its modes and forms, its feminist vision, and its literary and conceptual sophistication.

Order Chinese Fish on the Giramondo website, or find it in your local independent bookstore.

Additional coverage

‘Australia’s richest writing prize goes to Melbourne poet for family saga’ — Sydney Morning Herald

‘Debut poet Grace Yee wins $125,000 for ‘feminist vision’ at Victorian premier’s literary awards’ — Guardian Australia

‘I want to celebrate Astro, the robot boy I loved’: A poem from Television by Kate Middleton

Read a poem by the award-winning poet Kate Middleton. It appears in pages 14-5 of Television (1 February 2024), a collection in which Middleton considers the emotional impact that television programs had on her formative years.

Author note: Kate Middleton on Television

The award-winning poet Kate Middleton reflects on Television (1 February 2024), a collection which is part criticism, part autobiography, and always acute in its recollection of the emotions inspired by television drama.

In 1986 I wanted to dress like Punky Brewster. Like her I had dark hair and freckles and a talent for enthusiasm. I wanted to sleep in a flower cart and paint a rainbow on my wall. I wanted to stride into my class as confident as her and make friends with all the kids I met.

In 1992 Brenda Walsh seemed to represent my struggles: she was an outsider, moving from Minnesota to Beverly Hills with her family, and she wanted desperately to be cool. Which is to say, she wanted the right friends, the right clothes, the right boyfriend, the right future.

In 2000, I wanted to be Willow Rosenberg. The moment that she told Buffy she was turning down all the fancy universities that had offered her a free ride because she wanted to be the best witch she could be and face down the evil she had already seen too much of right at the lip of the hellmouth, I found her idealism infectious.

I could go on. I still turn on the television and find myself, among all my critical thoughts and aesthetic responses and guesses at the next plot twist, imagining myself into the lives of characters I somehow identify, or over-identify, with. I find myself imagining their qualities into my own life, trying them on, keeping those that seem important in my pocket for a time.

When Rilke says you must ‘change your life’, it is a treasured epiphany. When the Pretty Little Liar Aria Montgomery says something like it, it’s silly. I love Rilke, but I admit that I took in Aria’s epiphany a little more, because my own life is filled with similar frivolities to hers, if not with the same horrors.

I knew a few people as a schoolkid whose families did not own televisions, and I thought they were better than me. They could use their time wisely. They would not be infected by this nonsense that obsessed me. They could live more like Anne of Green Gables, a character I also carried with me, from the page, into a world full of broadcast technology she wouldn’t have recognised. In a way, I probably still think those people are better than me – but I can’t write about what I am not. I have watched a lot of television, as most people my age probably have. I have tried in this book to think about that time watching television not as escapism, but as, in some way, real experience – experience filled with memories and images and emotions that I carry with me into the real world.

Chinese Fish by Grace Yee shortlisted for Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards

Grace Yee’s debut collection Chinese Fish has been shortlisted in the Poetry category for the 2024 Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards.

Wrote the judges:

Chinese Fish switches between lyric, dramatic and documentary poetic forms, to tell a multi-generational tale of the Chin family’s migration from Hong Kong to Aotearoa New Zealand. Yee focuses on women’s experience; particularly, how migration tests the relationship between a mother and her daughter. She tells this story with sparkling humour, wit, and stylistic verve, while paying sustained attention to historical circumstance – particularly everyday racism and the discriminatory government policies which affected Chinese migrants. Characters’ voices are interwoven with archival text and scholarly observations. Cantonese-Taishanese characters, peppered throughout the dialogue, enhance a reader’s connection to this fictive family and their past. We were impressed by how intelligently Chinese Fish braids its modes and forms, its feminist vision, and its literary and conceptual sophistication.

The winners will be announced on Thursday 1 February 2024 at a ceremony in Melbourne.

In the awards’ Fiction category, Max Easton’s second novel Paradise Estate was also Highly Commended.

Three vignettes from Paradise Estate by Max Easton

On a muggy, bright and rain-spattered day in November at the low-slung Pratten Park Bowling Club in Ashfield, Max Easton launched his second novel. Almost two years had passed since the launch of Easton’s first, The Magpie Wing, which also celebrated its entry into the world at the bowlo, and which went on to become a finalist for the Miles Franklin. In the nearby suburb of Hurlstone Park, and perhaps known only to Max himself, was the real-life house that the author walked by a few years ago and began him thinking about the book which would become Paradise Estate.

The launch featured live music from local bands Mope City and Zipper, as well as Max reading of six ‘vignettes’ from the pages of Paradise Estate. Three of these vignettes have been published below.

From p.71

Dale bought another round for the old fellas at the Crystal Palace Hotel. He’d been roped into their conversation about former State of Origin greats, and while he usually liked to drink alone, he appreciated this excuse to keep drinking. After some hectoring, Dale told them about the circumstances that lead to him being made redundant (‘who doesn’t wank at work?’ the eldest at the table said, and when the youngest was hesitant to support Dale, the older man yelled: ‘what are you a priest?!’). Dale laughed meekly with these people, who he felt a comfort with, a generation who had never picked him up on his behaviour. To most that he knew, he didn’t seem to come across as ‘likeable’, and it showed. He’d react pre-emptively to the distaste he saw people feel towards him. It made him sensitive and jumpy, and when stretching that energy over a day, he became tired, and gaunt. And that made him look unwell. If he told friends about this anxiety, they’d try to reassure him by saying, ‘it’s all in your head’ but he would reply: ‘I know! That’s the problem!’ Then his friends would run out of patience and advise him to seek ‘professional’ help, which yielded the same advice delivered over several hour-long sessions—only it came with a bill attached, and sometimes a prescription. He was constantly humming with this energy, his eyes darting, his breath short and laboured, trying to take his ex-girlfriend’s advice, that: ‘no one could possibly hate you as much as you hate yourself.’ That had never helped either.

From p.81

‘Nathan, I’m sorry to bring this news to you, but we’ve received another complaint about one of your essays. It’s an anonymous one again, so we’re not sure how to take it. It’s…another plagiarism accusation. If you can call me back when you get a chance…that’d be great. Thanks.’ Nathan knew this one wouldn’t stick. This ‘anonymous’ member of the community going to each of the editorial committees he volunteered his time to, picking apart every word he said and claiming it was someone else’s work. He was no more a plagiarist than anyone else! Sometimes he’d receive a good pitch by a new contributor, reject it, and write it up as his own, but no one could pin that on him as far as he could tell. This complaint suggested that his recent article (criticising the She-Hulk production team for deflecting criticism of the show’s low-quality CGI by claiming it was ‘body shaming’ the titular character) had an identical argument to an essay published years prior (a defence of the Joker movie’s location shoot at a stairwell in Harlem that since became a tourist destination, stating that any critique of a unionised location shoot gave fuel to the push towards all-CGI sets). In the end, the editorial board had to throw out the complaint; Nathan had published the She-Hulk essay under his own name, and the Joker article under a pseudonym.

From p.162

‘What’s wrong?’ Sunny asked a pale-faced Helen, who entered their shed with a bucket of KFC at midday. ‘I went into the church,’ she said, looking overawed, ‘there were nuns.’ When Sunny started howling in laughter, Helen snapped, saying that ‘it’s too fucking cold’ and she needed some reprieve from the winter. Too fried after her all-nighter on Beth’s acid to get any further than the corner of the street, her blankets damp to the touch, shivering through the house, hoping there might be some kind of warm snack inside the church to tide her over until the KFC opened. ‘One of the nuns talked to me,’ she said conspiratorially, starting work on her bucket, ‘she knew about our house. She told me to take a seat. It was really weird.’ Sunny took a piece of chicken and tried to find a deeper psychological reason for Helen’s decision to walk into a church for the first time in her life, but Helen grew impatient, took her chicken away from them and said that no, she wasn’t in need of help from a higher power, because she was ‘beyond redemption anyway.’

Max Easton: a note on Paradise Estate

Sydney-based author Max Easton reflects on Paradise Estate, a book which occupies the same universe as his Miles Franklin longlisted debut, The Magpie Wing. Paradise Estate was released in October 2024.

The writing of Paradise Estate started on the week of The Magpie Wing’s launch in December 2021. A few people had asked if I was working on anything, and it was easier for me to claim that I knew what I was doing than to admit to how lost I felt. ‘I’m planning a book set entirely in 2022,’ I said. (That week, I’d gone for a long walk around the neighbourhood and passed a house in Hurlstone Park, signposted with For Lease signs belonging to three different real estate companies, flanked on each side by apartment blocks). ‘It’s set in a sharehouse with no privacy, on the edge of a suburb being swamped by development,’ I continued. ‘No it’s not a sharehouse novel…it just features six people cohabiting in their thirties because that’s the way it is now.’ And while at the time it all felt rushed, and hurried, and motivated by social anxiety: I look back at the final edits this morning, feeling like it all went to plan.

Of course I’ve embellished the hastiness of the book’s setup. I had been thinking a lot about years of historical significance. It was on my mind since the writing of the Barely Human podcast (isolating points over a fifty-year history during which countercultural action slipped into subcultural practice) and was sparked again by The Magpie Wing’s timeline, when it hit the 2010s and each year seemed to blur into the other.

Going into 2022, I thought it would be fun to explore the meaning of what felt like potentially another miscellaneous year…but then things kept happening. A war took the world’s attention and instigated the start of a recession; extreme weather events were laid one atop the other; the pandemic continued despite our wilful ignorance; the housing crisis finally became a discussion point; and governments changed hands with no signs of curbing any of the above. I tried to take notes and wrap a narrative around all these events, to find parallels by way of allegory, to satirise the process itself as I went, allowing the march of 2022 to dictate the progress of the book. It was much more of an experimental process than I imagined, and it took a lot of work to bring it into some kind of order. Finishing a book in 2023 that was all set in 2022 has done all kinds of weird things to my perception of time, and I wonder if that’s a personal effect, or something that will flow on to the reader.

I should mention that Paradise Estate picks up a timeline shortly after the end of The Magpie Wing via the character of Helen (that’s a sophisticated way of admitting this is more or less a sequel). This one is written so that you can read them in either order, and I think it’d be an interesting way of parsing time, going from the fine-angle lens of Paradise Estate’s 2022 to The Magpie Wing’s twenty-five year history. It seemed to me that sequels aren’t really a done thing in contemporary literary fiction, and while I’m not sure what the wisdom is there, it seemed like every reason to write one.

Thanks to whoever takes the time to read Paradise Estate, and to everyone who helped bring it through to completion.

— Max Easton, August 2023

Praiseworthy and Harvest Lingo win Queensland Literary Awards

Alexis Wright’s novel Praiseworthy and Lionel Fogarty’s poetry collection Harvest Lingo have both been named winners at the Queensland Literary Awards.

Alexis Wright’s epic novel was presented with the $15,000 University of Queensland Fiction Book Award, and also shortlisted in the Queensland Premier’s Award for a Work of State Significance. The judges said of Praiseworthy:

The great Moana Jackson declared the doctrine of discovery a legal fiction. In Praiseworthy, farce, satire, tragedy, the colloquial, myth, pun, repetition, elegy, and the epic expose the absurdity of the doctrine and the everyday lies, habits and horrors keeping it in place. Praiseworthy is simply astonishing.

Lionel Fogarty’s collection Harvest Lingo, which has already been shortlisted for the NSW and Victorian Premier’s Literary Award, received the prestigious $15,000 Judith Wright Calanthe Award for a Poetry Collection. The judges said of his book:

Deliberately diverging from the status quo, Harvest Lingo offers a sovereign alternative to standard ways of poetic thinking and reading. Continuing his revolutionary tactic of critique via his personal powerful, poetic language, Lionel Fogarty subverts and disrupts white capitalist structure and its confinement of and lack of knowledge of Indigenous life and culture.

Several Giramondo titles were also shortlisted in the awards: Shaun Prescott’s Bon and Lesley for fiction, and Michael Farrell’s Googlecholia and Autumn Royal’s The Drama Student for poetry.

Congratulations to all the winners and finalists.

Transcript: Marion May Campbell’s launch speech for Chinese Fish

Chinese Fish by Grace Yee (June 2023) was launched at The Alderman in Brunswick East at a sold-out evening event. The launch included readings by Yee, as well as from fellow ex-Aotearoa poets Alison Wong, Saradha Koirala, Xiaole Zhan, romesh dissanayake, and Manisha Anjali. Poet, novelist and academic Marion May Campbell wrote the launch speech, which was delivered by Lisa Gorton on the night. Read a transcript of Campbell’s speech below.

Chinese Fish is a brilliantly devised, comic feat of cultural resistance; a fantastically polyphonic verse novel majoring in riotously funny and heartbreaking ways, the minoritised experience of three generations of a Chinese family, who in the 1960s migrate from Hong Kong to Aotearoa / New Zealand, or, as white Australians hypocritically used to joke, the land of the wrong white crowd.

Its most intense emotional charge comes from the struggles, triumphs and resistance of the female characters. There’s the doubly silenced Ping, crushed and exploited both by internalised patriarchal oppression, emotional neglect by husband Stan, and the pervasive racism, both blatant and casual from the host country, and there’s her feisty Hong Kong-born, first child, Cherry, whose coming-of-age story the work also intermittently charters. But Stan and Ping’s other children, Joseph, Lenore and Starlit, a host of minor characters, co-inhabiting in-laws, neighbouring kid bullies and friends, also emerge vividly alive through the narrative fragments.

The economy, dramatic verve and imaging give these fragmentary story-worlds an almost hallucinatory intensity. Uncompromisingly, Grace builds this tessellation of poetic and dramatic fragments into an ever-more resonant mosaic, allowing the reader to circulate in freely imaginative participation in the gaps. The work is all the more brilliant for eschewing the conventional lyric and also for being free of polemic and interpretative commentary. The voicework performs the scenes for us throughout, setting into friction the dynamic exchanges between family members, in their Cantonese-inflected English, (with interruptive Chinese characters), plunging us directly into each newly unfolding stage of their material and white-bread, milk-tea cultural accommodation to suburban middleclass life, with the virulently racist Sinophobic journalistic diatribes, slogans and casual slurs, playing in their grey font like a gruesome drizzle through the text.

It’s an ingenious mode of poetics driving the work (in all its experimental graphic, spatial, and narrative dimensions) and it’s all the more remarkable, that despite the jamming of speech acts from a huge range of genres, with their culturally saturated images, ads chanting the seductions of new domestic appliances, or the visceral intersplicing of body events in pain, danger and pleasure, the multiple stories emerge with a secure dramatic contour.

Through the voicework, Grace unfolds the often ingenious and sometimes desperate ploys of the family’s adaptation to a frequently hostile culture, with passing and subterfuge working as oblique resistance. Grace’s satirical brio, her delightful riffs on the absurdities of masculine behaviour, for instance, her deflating laughter before injunctions to aspire to conventional feminine beauty, and her complete eschewal of sentimentality before even acute suffering – all sustain the reader’s empathetic connection as they participate in the community.

The painfully edged comedy of daily survival is pervasive, though. A major motif that runs through the verse novel’s seven sections is the rat-plagued fish and chip shop, which is the economic engine driving the family’s quest to thrive:

Or we could look at the way the cinematic montage swoops us to the centre of sacrifice and pain: after a wonderfully abbreviated sequence of who is doing what in the household, we find Ping (whom we know from Grace’s vivid and succinct evocations to be clever and beautiful), throttled into illness by endless hours of enslavement over the fish, chip, and sausage vats, on top of all the domestic labour with the big extended family, venting her sorrow regarding her faithless husband. (p.50) And later (p. 87), her rage emerges: you dead man you dead man you dead man.

But this rage is countered by the delightful evocation of Cherry’s coming-of-age, her experimentation with Punk gothic rebellion with her superb friend Delia, and her sampling of Pākehā boys’ attractions.

How about Grace’s parodic verve here, poking her tongue at the persistent orientalism corroding the ‘politically correct’ veneer. Here’s nothing like laughter to undermine the power of the would-be assimilationists and to disarm virtue-signalling Anglo-Celt post-colonialist critics.

It’s impossible in a few minutes to account for the extraordinary richness of this masterwork with its myriad story-worlds, bestowing us a host of gorgeously flawed and entirely engaging characters.

Chinese Fish is a great artistic triumph that I do hope you can fully celebrate tonight, and that deserves all the critical accolades it will surely attract.

Congratulations Grace!

Transcript: Grace Yee at the launch of Chinese Fish

The poetry collection Chinese Fish by Grace Yee was published in June 2023, and celebrated its launch at The Alderman in Brunswick East. A work which ‘portrays the fractured, multilayered, imperiled body of the immigrant story in a stunning work of genre-bending prose poetry’ (Juli Min), it brings us into the daily lives of a multi-generational family newly settled in Aotearoa, New Zealand, where Yee grew up. The book’s launch speech was written by Marion May Campbell, and delivered on the night by Lisa Gorton. Read a transcript of the speech presented by Yee at the launch below.

Thank you Lisa, and thank you Marion, for your generous words.

I am hugely grateful for Marion [May Campbell]’s support from the inception of this book, which began as part of a PhD project, and for her generous support for my work in the years since.

I am also very grateful to Lisa [Gorton] for editing Chinese Fish – Lisa’s guidance and suggestions, particularly on characterisation and voice, challenged me to think more deeply about the work.

Thanks to Ivor Indyk and the Giramondo team for taking a chance on the manuscript; to Aleesha Paz for extraordinary attention to detail, and Kate Prendergast, for her tireless marketing and promotion.

Thank you, Alison, Saradha, romesh, Manisha and Xiaole, for your kind words and brilliant readings. I feel honoured to be in your company and look forward to reading more of your work.

Huge thanks also to Fran Martin, who supervised the critical component of the thesis that accompanied Chinese Fish; to Ely Finch, for expert guidance on the translations – and the pronunciations!

To Zachary Wong, for the illustrations; to my early readers Alison Wong, Coral Campbell and Helen Gildfind, for reading numerous versions of the manuscript; and to my family and close friends for practical and moral support over the years it has taken to complete this book.

There was a comment that Marion made on a very early draft which has remained with me. It was in response to a series of vignettes that I’d forwarded to her, which were narrated in a single omniscient voice.

The comment was: ‘it’s important that there be levels in the work, that lend a kind of poetic hospitality.’

I love this idea of ‘poetic hospitality’, of openness in a text, of spaces between levels – or layers – that allow readers to visit with the text – to sit with it, to enter, leave and re-enter…

I didn’t strategically create different levels in Chinese Fish, but the more research I did, the more voices I heard, the more I felt that this story needed to be narrated in multiple voices.

So there’s Ping, the long-suffering wife and mother who migrates from Hong Kong to Aotearoa, with her husband; there’s Cherry, the eldest daughter, who has to navigate the space between the patriarchal Chinese home, and the outside Pākehā world.

There’s the serious voice of the scholar, and the colonialist orientalist mainstream narrator, a voice inspired by the archives, that parodies orientalist tropes and stereotypes, which haven’t really changed that much over several decades – the epithets and exoticisations that I grew up with are not so different from the ones I read in late 19th century newspapers, or hear on the street today. Chinese culture has often been described as ‘traditional’, ‘timeless’ and unchanging, but maybe it’s the orientalist lens that is fixed in its stare.

I had a lot of fun playing with the voices in the book: Ping is inspired by my mother and the women of her generation who migrated to Aotearoa as newlyweds to Chinese New Zealand men. The English they spoke was typically ‘broken’ and integrated with other Chinese languages. My mother and aunties spoke Cantonese, Taishanese, English, and occasionally Mandarin, fluently – but often mixed two or three of these together, in the same breath.

We all grew up communicating in this hybrid language that we later couldn’t teach or hand down to our own children, because it was so make-shift, transitional, the kind of bridge that is gradually dismantled over the generations once the family becomes more established in the new land.

I am very happy to have written a little of it down now for posterity, in this book.

I will now read a selection of poems from Chinese Fish, with the assistance of my friend, Coral.

An excerpt from π.O.’s The Tour

Featured here, an excerpt from π.O.’s The Tour, published in 2023. The book is a road trip in verse, narrated by one of a group of Australian poets undertaking a tour of the United States and Canada. π.O. is considered one of the pioneers of performance poetry, and The Tour can be read as a chronicle of its difficulties and triumphs.

Transcript: Sanya Rushdi at the launch of Hospital

Sanya Rushdi’s debut novel Hospital was published in Australia in June 2023, and launched at Readings State Library in Melbourne. Narrated in the first person, the book is a literary account of a woman living with psychosis, and is based on Rushdi’s own experiences. Read a transcript of the speech presented by Rushdi at the launch here.

Dear Audience,

Peace be upon you!

What a way to spend a Friday night, aye? I mean, you could have spent the night with friends and family. Perhaps watching a movie, or watching Friday night sports or cooking up a big meal for the dinner party. Instead, you decided to be here at my book launch! I am humbled, honoured and grateful. Thank you for making the time to be here.

Let me first warn you of the fact that I am an extremely bad oral communicator. So please forgive my shortcomings.

You may be saying that: “how can that be even possible? You wrote an entire book for goodness’ sake!”

To that, I just want to say that: “Yes, I wrote a book called Hospital, but, as Vygotsky said in Thought and Language:

…the mental functions which form written speech are fundamentally different from those which form oral speech. Written speech is the algebra of speech. It is a more difficult and a more complex form of intentional and conscious speech activity.

Of course, there are differences other than intentionality and level of consciousness between oral and written speech. For example, oral speech usually occurs between two or more people, and the sentences can be left incomplete for the other people to complete them, which, I think forms some kind of mental connection between people, whereas, written speech is usually more expanded and even monotonous.

However, there are different ways of reducing the monotony in written pieces. Written pieces can be written out as different characters speaking to one another, for example. That’s what novels tend to do. They use dialogue, which, I too, have used extensively in Hospital.

In the novel called Hospital, the protagonist receives a diagnosis of schizophrenia after her third episode of psychosis. Psychosis or schizophrenia is something that most people find interesting if not fascinating. It’s one of those colorful illnesses that keep normal people wondering about what’s going on in the affected individual’s mind. There are other, less colorful mental illnesses too, like clinical depression, which is perhaps more devastating and debilitating than most cases of psychosis. Yet, psychosis steals all the public attention – negative attention, to be clear. I experienced both, and want to see one in light (or should I say darkness) of the other.

If there is anyone in the audience who is experiencing, or knows someone who is experiencing some kind of mental illness, know that this darkness does not last forever. It subsides in due time. Often, change starts with something very little, like keeping a diary and writing in it whatever comes to mind. That’s how my writing journey began. During my depression, my elder sister Luna used to ask me write whatever would come to my mind, and afterwards, I could read it out to her if I wanted to. I mostly wanted to, because during major depression, one is in constant need of human interaction. The TV doesn’t do, the internet doesn’t do too much, it’s the actual presence of other people that leads to healing. I remember my younger sister Ifa and her family used to make time to take me out to the beach (which I used to find very soothing) or recite for me from the Quran, or dine with me, or whatever they could, to keep me company. I remember Ifa’s sister-in-law Farhana Snigdha and her family visiting me often. And of course my parents, Sultana Rushdi and Ali Ahmed Rushdi, my ex and my extended family did for me what was beyond my imagination, beyond what I could ever expect! But I just want to say that even if you can’t have all the support that I had, just starting from something very little is often the start of big changes.

Hey, I never thought I’d write a novel. But it’s the writing habit that I built up by keeping a diary, together with the help and encouragement of my beloved Tanvir Ahmed Chowdhury, my publisher and friend Bratya Raisu, and my friend Monzurul Ahsan Olee that led to the completion of the original, Bengali version of this novel called Hospital.

So, how did I go about writing the novel? A couple of months after returning home from the hospital, I became very eager to share my story with a caring ear. So, I gave a few pages of writing to a friend of mine, Bratya Raisu, who is a publisher and editor for a couple of online magazines (and also a renowned poet, writer and artist). Raisu asked me to develop my story into a novel, because he thought it had all the material for a good novel. I was hesitant to start writing a novel so he asked me to give him some chapter headings – just one to two lines of what can be expected in each chapter. I did that, and upon writing the first chapter, it was published in shahitya.com, and subsequently chapter by chapter there. Although I didn’t end up sticking to the chapter headings, it was a rough guide to start with. Each chapter just flowed from the last spontaneously and naturally afterwards.

Later, after the book was published in Bengali, my elder sister Luna sent a copy to Arunava Sinha, who is a friend of hers and is a renowned translator in India, the UK and the US. Arunava read the book and expressed interest in translating it into English, which was a very humbling and happy experience for me. Translating, at his level is a big thing. I’ve read somewhere that ‘writers write for local readers, whereas translators translate for universal readers’. Following Arunava’s translation, the novel received international attention. The English version of the book was published by Seagull Books, and the wonderful Giramondo Publishing Company in Australia, working with whom – my publishers Ivor Indyk, Evelyn Juers, Nick Tapper and the entire team including Kate, Aleesha and others who are working behind the scene, has been an absolute pleasure and honour!

As shown in the novel, psychosis can occur without depression and vice versa, just like obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) can occur with or without anxiety disorder. Although mainstream psychology and psychiatry do study the aetiology of different mental illnesses, they do so in fragmented ways. Vygotsky compares this method to studying a fragmented water molecule. As we know, a water molecule is composed of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom. Both hydrogen and oxygen are combustive in isolation, but when they are within a water molecule together, as H2O, their characteristics change. Indeed, the characteristics of a water molecule is completely different to that of its isolated atoms.

I think, in a similar way, the different mental illnesses can be compared to see whether they occur together in certain personalities and mind sets, races and nationalities etc., and in cases of multiple mental illnesses, and multiple incidents within a person, how they develop from one illness to another and what happens in-between the incidents other than just ‘resistance to medication’. I think the aetiology of mental illnesses should be studied using more non-mainstream, naturalistic and qualitative methods.

Looking back at my own experiences, I found that in clinical depression, I felt as if I was unable to do the things I previously enjoyed, because there was an internal block that excluded me from feeling any pleasure. Time passed very slowly and there was a frequent thought of death, not because I was grieving something, but because I felt no pleasure in anything at all!

Psychosis is a bit different to clinical depression. For example, during my three incidents of psychosis, time passed so quickly, that I felt as if I could not keep up with the “tasks that needed to be done.” This speed of passing time, however, did not happen from enjoyment, but from a constant agitation, restlessness and irritation due to a feeling of persecution in my first two incidents and a feeling of responsibility and accountability in the third. The last incident seemed to be without much agitation and restlessness, as was shown in Hospital.

So, in psychosis, one feels as if one is unable to do the things one enjoys or thrives in because there is an external pressure of some sort to do otherwise.

But wait a minute. Doesn’t this description of psychosis apply to life in the present world in general too? Is mental illness and mental health a matter of two different languages used by the ‘normal’ and the affected individual? That’s something that Hospital hints at, and it is for you to find out.

Thank You!

‘Green mantis’: a poem by Luke Beesley from In the Photograph

‘Green Mantis’ appears on pages 99-100 of Luke Beesley’s 2023 work of prose poetry, In the Photograph. The genesis of the work lies in a morning ritual Beesley performed while still a PhD student, where he would rise at dawn to write in the ‘slipstream of a dream’ in a Thornbury cafe. Beesley reflects in his author note that ‘over years of editing, the often-surreal images of these poems have become as strong, if not stronger, than my own memories.’

For the second time I went to the author and told her I had read her book. She said she’d only just finished it, waving her hand out at the room. I followed her frail hand, and it opened the space out to me. It was a darkly lit pub with numerous hollows and a waiter moved effetely with a long match and lit small tea-light candles in terracotta pots. What came to me was a memory of India, a decade before, twisting sideways to fit through the misty air between two hanging hand-woven rugs—a corridor.

Oh, look! There’s so and so, said the author (it was the editor of the national literary papers). I could see a review in his eyes. Recognising me, his face frowned thoughtfully in critique. But he passed on. Phew, said the author, and I felt her breath on the hairs of my forearm. My forearm moving across the page!

I sipped water provided by the pub and brushed biscuit crumbs. I said to the author, or I wanted to say: What do you mean you just finished it? I’d slept poorly. A mouse trap had gone off in the night, the night before, and I’d woken with my startled heart racing, listening for a thrash in the dark. I’d wondered whether to get up and check the trap. At this, the author seemed like she was again to open out her hand to the room, but she showed me the ink staining the inside of her arm where it had met the page. Her papery skin stayed in my mind as I looked up from her arm.

She was shorter than I’d remembered and had expressive eyes. Her voice seemed circuitous, but I’d begun to realise that it was often like this. I described the effect of her first paragraph, and I said yes. She raised a finger and dabbed at the side of her lip and the candleflame swayed briskly like a mantis on a branch or, to put it another way, I tried, again, holding my arms, elbows, to go over that paragraph. I pictured it in my mind—actually, I followed the sentence back before civilisation had a wheel—and there it was.

She stepped back with a polite expression as I turned. Here, writing again, tearing little knobs, bows and loops into the paper. Knitting on a line beside coffee, where I saw the actual author in the seam, and in the pub, and in the air.

Perhaps you reached the end? she said. And I remembered saying I’d only just begun and was savouring the book, but I must have forgotten my place. Heat in my face and the smell of stale beer and the pub’s sticky thick carpet. I stood groggily and held my hands out as if to say kudos. But she took them, confused herself, perhaps, and in my hands were pay packets—a few folded notes, small change, and she released her hands and gave me a copy. It was fresh. My mouth opened, not in joy but praise, quiet surprise—a shiver looking up to find the author not there.