Bonny Cassidy

Author note: Bonny Cassidy on Monument

The award-winning poet and writer Bonny Cassidy reflects on Monument (1 February 2024), her first work of non-fiction. Moving seamlessly through genres in its recovery of the past – part poetry, part prose, microhistory, memoir, travel writing, and sometimes counterfactual speculation – Monument traces the complex consequences of colonial settlement across the generations of a White Australian family of mixed origins and ancestries. You can also read an interview with Cassidy in issue 38 of Rabbit.

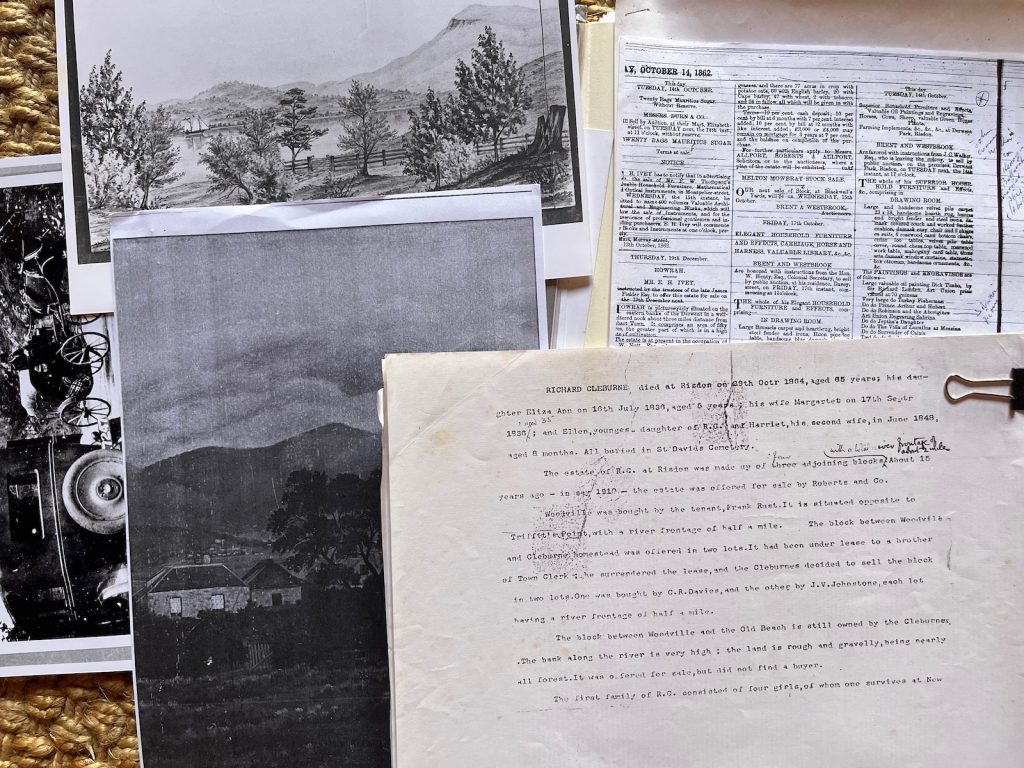

The research for this book began as a private path; enclosed. While there were signs in stories and documents about some of my relations’ lives, most of the first, second and even third generations in Australia were unlettered and untold. As I quickly found out, this ignorance is common amongst White settlers.

For a couple of years, I travelled around and riffled archives to learn those lives from scratch, or to test the well-trodden parts. I sought out people who I felt could help me gain an understanding of what and who were encountered by my family’s first generations on an already occupied continent. A way to bear witness, my searching grew into a fantasy of reconciliation. I would, I imagined, make deep connections with communities with whom my family has no living link. I would re-start the past.

Eventually, I realised that of course this fantasy could not be fulfilled. Writing a book could not stand in for such relationships. It could not be an express ticket to trust from communities that have often found their trust betrayed. And writing a book alone, no matter how many sources I consulted, would not constitute justice. Moreover, the fantasy was a distraction from what had become abundantly clear: I had to get my own story straight.

What I find in Monument is a shadow text. A way towards something else. I still might have let this remain a personal store of reference and research, but it had already gotten away from me by connecting with other writings, histories and events that were taking shape out in the world. I have thought a lot about what non-Indigenous people might contribute to the growing wealth of First Nations truth-telling. This book stands adjacent. I think of it as storytelling and sometimes, when it’s corroborated by sources that vary from colonial authorship, as history. While much of my work was meant to seek overlaps, the gaps in it show me what can be forgotten, what recovered, and what paths lie beyond the emblematic nature of a book.

An excerpt from Bonny Cassidy’s Monument

The following excerpt is from Bonny Cassidy’s Monument (1 February 2024), a hybrid literary memoir which views white settler family history against the impacts on the Indigenous people with whom the family members interact.

In the 1830s two young Palawa men, Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener meet George Augustus Robinson, Chief Protector of Aborigines for Van Diemen’s Land.

Tunnerminnerwait is a Parperloihener man of the north-west coastal nation of lutruwita, Tasmania. As a child he witnessed a massacre of his people at Cape Grim. Maulboyheener is of the Panpekanner group from the north-east tip of the island. He has never known his younger brother, who was taken as an infant from their mother by the English squatter, John Batman. Robinson is an Englishman, a builder by trade, tall with a good deal of strong flab. He keeps a journal.

His story is raked over by historians and writers. Robinson seems to be eternally fascinating and inscrutable to us whitefellas. We have hoped him to have been some sort of noble settler, and yet.

The Governor of Van Diemen’s Land has given him a mission, to meet all Palawa groups and persuade them to join a settlement at Flinders Island in the Bass Strait. Robinson proposes that the Palawa be permitted a reserve on Van Diemen’s Land so that they can remain closer to Country, but the Governor rejects the suggestion. The land is too valuable and the danger too risky – to everybody – he says. The Governor much prefers the idea of sending Robinson off into the forest. He never expects the Chief Protector to return, let alone walk into Hobart one day with a deputation of clan leaders.

Trudging around the island on foot, covering unfamiliar distances and negotiating meetings, Robinson is plagued by rashes during his journey through the estuaries and forests. He sneaks away from camp before dawn to wash, imagining he can’t be seen. His most treasured thing is the rucksack containing his journals of names, language, customs and travels: the journals are intelligence, and his legacy.

Robinson introduces himself to as many Palawa as he can. If they’ll just stick with him, Robinson reassures Tunnerminnerwait, Maulboyheener and the others he meets, they will be able to return to their homelands later. He knows this isn’t what the Governor has agreed to, but Robinson is confident enough in his own powers to believe he can make it so.

And what do the Palawa believe? Their warrior ranks are shrinking, elderly and kids are getting left behind in the warfare, and the number of settlers is rapidly multiplying. How do the Palawa, daily and in diverse groups, negotiate between their will to survive and any settler’s offer of trust? We know that they accept Robinson’s promise to return them home, because of their outrage when he later breaks it.

As for me, I want to believe that Robinson is a true friend, not just a jumped-up chancer or a creepy preacher. Are his efforts of uncomfortable travel, intercultural friendship, language learning – things attempted by no other non-Palawa – really only made for the rewards of status and a salary? I want to believe that, knowing the apocalypse has already come to the Palawa, Robinson is building a safe place for them. And yet.

Robinson returns to the Governor with representatives from his ‘friendly mission’. They walk through Hobart. Before they sail to Flinders Island, Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener have their likenesses painted by the leading society portraitist, Thomas Bock. They are joined by Truganini, born on Bruny Island and wife of Wurati. They are also sketched by Benjamin Duterrau, who tells them he will put them into a painting with their Chief Protector.

The Flinders Island settlement, Wybalenna, is formed in 1834. Overseen at first by Robinson, its residents come from different homelands across Van Diemen’s Land yet are made to cohabit and work together under inspection. They comply with the roster of gardening, manufacture, worship and cleaning, while trying to maintain independent hunting and camping trips away from the settlement. And in just five years Wybalenna is rife with disease and death. Remote and offshore, run to a foreign moral code, language and roster of activity, it is what we now recognise as, at best, a permanent detention centre; at worst, a concentration camp.

At the deepening of his friends’ misery, Robinson chooses to move on. In what seems like a sudden attack of fatalism, cowardly embarrassment, or ambitious opportunism – or all three – he takes up as Chief Protector of Aborigines in Port Phillip, across the Bass Strait.

He tries to keep the relationships going with his closest friends from Wybalenna. In 1839, along with eleven others, Robinson asks Truganini and Wurati, plus Maulboyheener, Tunnerminnerwait and his wife Planobeena to accompany him as cultural liaisons at Port Phillip. They agree to go.

In their absence, things only worsen at Wybalenna. A series of punitive commanders is hired. The remaining Palawa resist. They are becoming increasingly aware that they will not be returning home, and that their good faith in the state’s mission has been abused. They leap the chain of colonial command: Maulboyheener’s elder brother Walter leads a petition to Queen Victoria to protest the community’s treatment.

Meanwhile, Tunnerminnerwait accompanies Robinson in his new role on the mainland. They travel to the west of Port Phillip, into Wathaurong and Gunditjmara lands.

Once he returns to Melbourne, though, Tunnerminnerwait keeps travelling. He joins with Maulboyheener, Planobeena, Truganini and another woman, Pyterruner. They move east around Port Phillip, in the opposite direction to Robinson, along Boon Wurrung Country to Western Port and Dandenong. Stations are ransacked and people assaulted. Eventually the Palawa group is apprehended for murdering two whalers.

Before Robinson’s mission, Truganini and her family were viciously attacked by sailors, sealers, soldiers and timber-getters back at their home on Bruny Island. All the southern coastal nations’ relationships with whalers and sealers have been long, complicated and bloody. The mainland murders will often be interpreted as a long-awaited reprisal. Maybe the slain whalers stand in for those who got away at Bruny; or maybe the Palawa group track and assassinate their targets across hundreds of kilometres of sea and soil. Or maybe they are now using violence and theft because, in the end, it seems the only language that invaders understand. I think of Trawlwoolway artist Julie Gough’s image, Manifestation (Bruny Island): a dining chair pierced by a spear, both on fire. They’re extinguishing one another on a rock shelf beside an estuary.

In court at Port Phillip, the Palawa travellers are not invited to testify for themselves. Robinson is the only witness in their defence. The three women are let off by the jury, but Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheener are sentenced for murder. In 1842, they are hanged before a huge crowd at Victoria Street, outside what is now the Old Melbourne Gaol.

There isn’t a chance for the travellers in that foreign courtroom to unfold their story, which is much bigger than murdered whalers at Western Port.

Their story isn’t mine, but I am standing by it.

Monument by Bonny Cassidy, pp. 9-13